Cultural Competence and Ethics Among Nurses in Primary Healthcare: Exploring Their Interrelationship and Implications for Care Delivery

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Rationale

1.2. Cultural Competence in Nursing

1.3. Ethics in Nursing Practice

1.4. The Interrelationship Between Cultural Competence and Ethics

1.5. Study Objectives

- To assess the levels of transcultural self-efficacy (cognitive, practical, affective) among nurses.

- To evaluate nurses’ ethical knowledge, ethical attitudes, and practices regarding common ethical and legal dilemmas in primary care.

- To examine the associations between demographic/professional characteristics and levels of cultural and ethical competence.

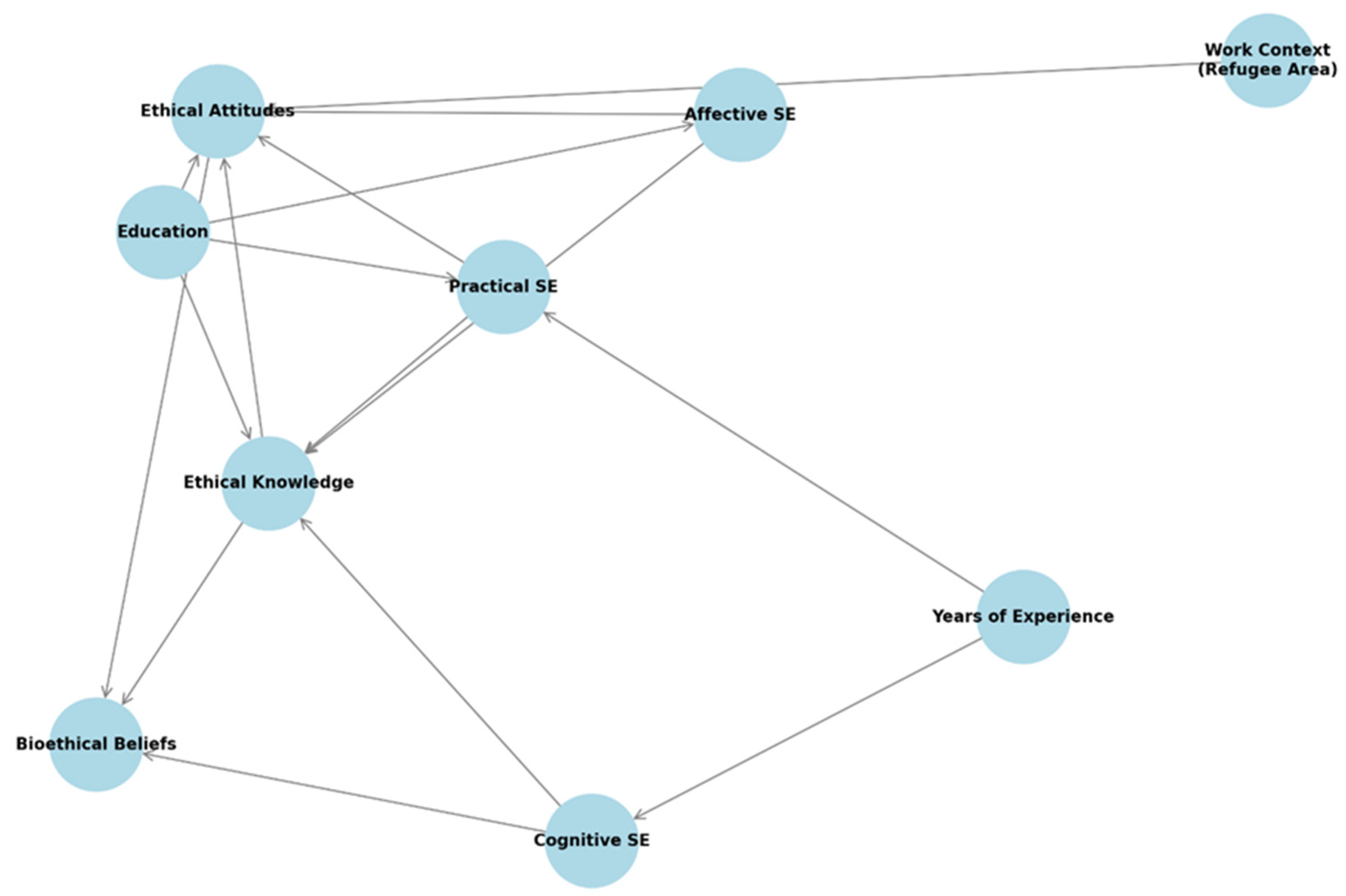

- To investigate the interrelationships among the dimensions of transcultural self-efficacy and the variables related to ethics.

- To identify predictors of transcultural self-efficacy and ethical competence using multivariate analysis.

- Higher educational attainment will be positively associated with greater levels of both cultural and ethical competence.

- Cultural competence and ethical competence will be positively correlated.

- Nurses working in more culturally diverse or ethically demanding settings (e.g., refugee-hosting areas) will demonstrate higher levels of ethical awareness and sensitivity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population and Sampling

2.3. Instruments and Data Collection

2.3.1. Transcultural Self-Efficacy Tool (TSET–Gr)

- Cognitive (25 items): Evaluates self-efficacy regarding knowledge of cultural factors influencing nursing care.

- Practical (30 items): Assesses self-efficacy in conducting culturally sensitive nursing interviews. Interview topics include items such as language preferences, religion, discrimination, and attitudes about health and illness.

- Affective (28 items): Measures self-efficacy related to respecting values, attitudes and beliefs concerning cultural awareness, acceptance, appreciation, recognition, and advocacy.

2.3.2. Nurses’ Ethics Questionnaire (NEQ–Gr)

- Perceived frequency and clinical impact of common ethical/legal dilemmas in nursing practice;

- Perceived relevance of ethical/legal knowledge in clinical decision-making, including knowledge acquisition pathways;

- Preferred consultation resources when addressing ethical/legal challenges;

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

3.2. Cultural Competence Levels Among Nurses

- 0.975 for the Cognitive subscale;

- 0.975 for the Practical subscale;

- 0.960 for the Affective subscale.

3.3. Knowledge and Attitudes of Nurses About Ethics

| Question | Response Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of Laws Related to Professional Duties | |||

| None | 11 | 2.2% | |

| A few | 168 | 34.1% | |

| Most | 232 | 47.2% | |

| Unsure | 81 | 16.5% | |

| Importance of Ethical Knowledge in Clinical Practice | |||

| Not at all | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Slightly important | 3 | 0.6% | |

| Moderately important | 79 | 16.1% | |

| Very important | 401 | 81.5% | |

| Unsure | 9 | 1.8% | |

| Sources of Ethical/Legal Knowledge | Formal education | 355 | 72.2% |

| Work experience | 365 | 74.2% | |

| Seminars/lectures | 145 | 29.5% | |

| Personal study | 191 | 38.8% | |

| Other sources (media/internet) | 76 | 15.4% | |

| Familiarity with Major Ethical Frameworks | |||

| Hippocratic Oath | 457 | 92.9% | |

| Nuremberg Code | 160 | 32.5% | |

| Nursing Code of Ethics | 403 | 81.9% | |

| Declaration of Helsinki | 142 | 28.9% |

| Statement | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Unsure | Agree | Strongly Agree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A patient who wishes to die should be assisted regardless of illness | 23.2% | 39.8% | 28.9% | 6.3% | 1.8% | ||

| A nurse cannot refuse to participate in an abortion when legally permitted | 7.1% | 17.9% | 28.5% | 37.8% | 8.7% | ||

| Children should not be treated without parental consent (non-emergency) | 0.6% | 4.1% | 15.4% | 43.9% | 36.0% | ||

| Organ donation should occur automatically without family consent | 21.5% | 32.7% | 23.2% | 16.1% | 6.5% | ||

| Statement | Respect the patient’s decision | Suggest the right treatment | Proceed without consent | ||||

| If a patient refuses transfusion/surgery/therapy, what should the healthcare professional do? | 15.7% | 80.7% | 3.7% | ||||

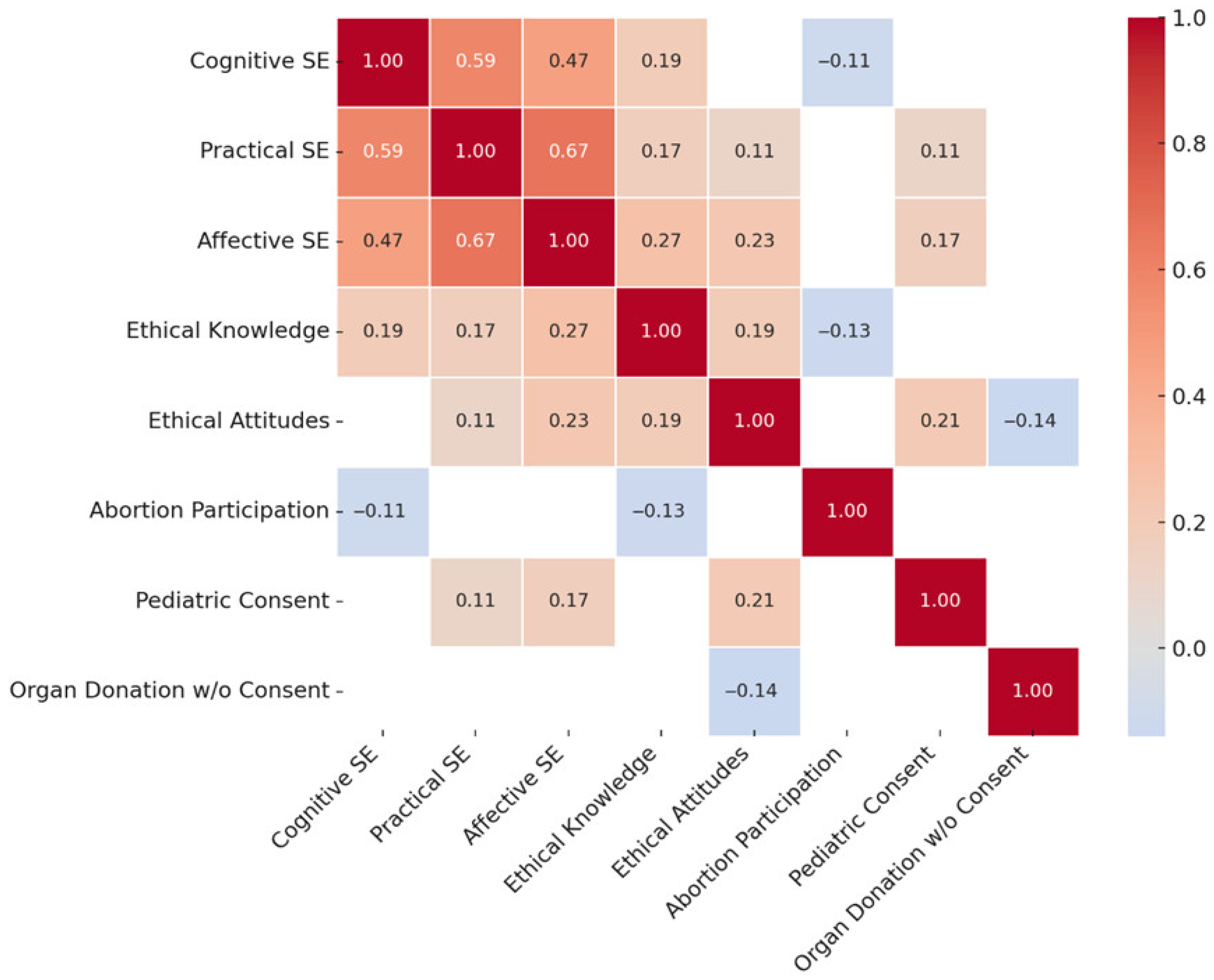

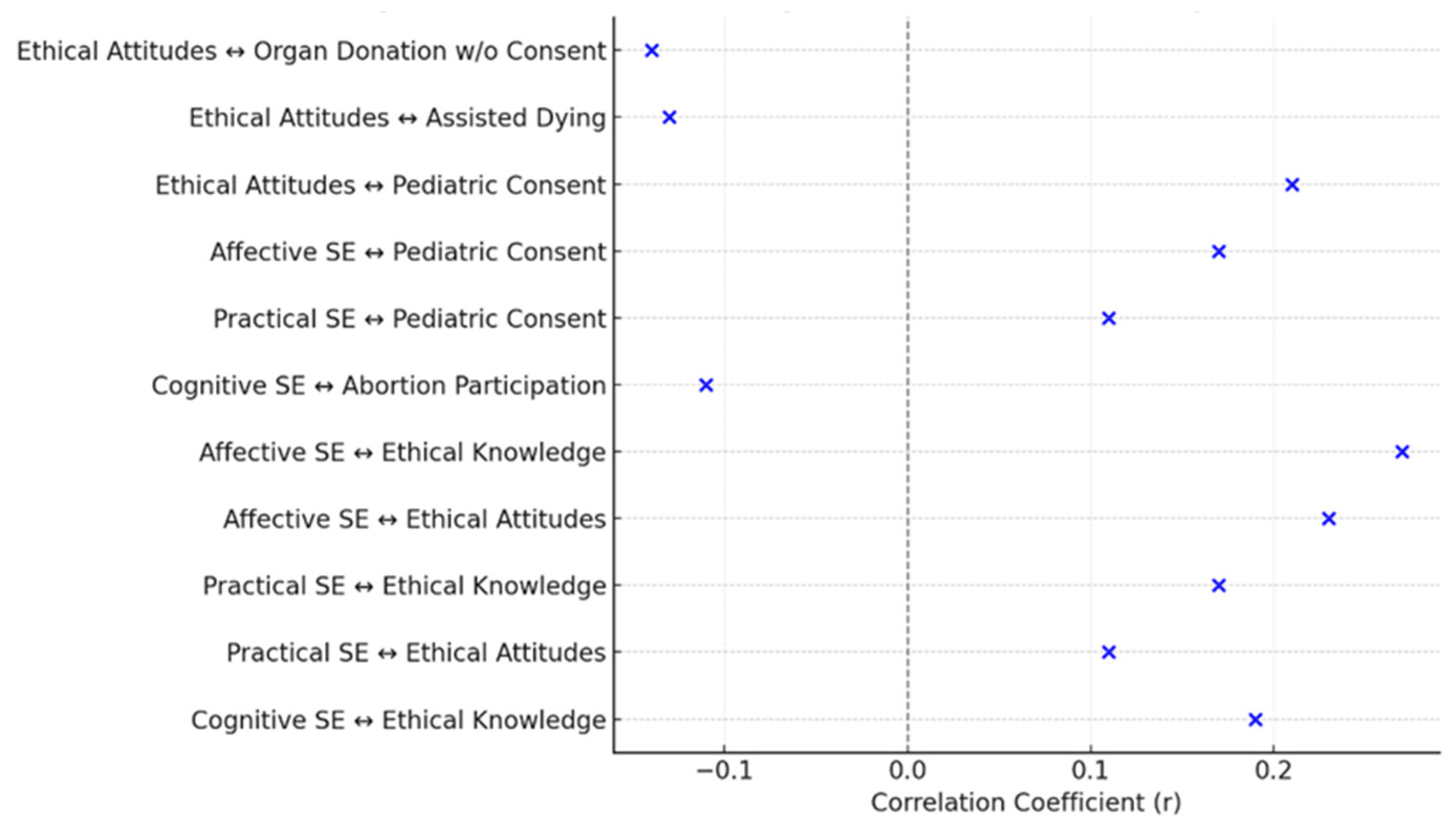

3.4. Correlations Between Cultural Competence and Knowledge and Attitudes of Nurses About Ethics

4. Discussion

5. Implications for Nursing Practice

6. Limitations of the Study

7. Conclusions

8. Recommendations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jaiswal, R.; Gupta, S.; Gupta, S.K. The Impending Disruption of Digital Nomadism: Opportunities, Challenges, and Research Agenda. World Leis. J. 2025, 67, 74–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Trends Report 2023. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/media/global-trends-report-2023 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Nursing and Primary Health Care: Towards the Realization of Universal Health Coverage. Available online: https://www.icn.ch/resources/publications-and-reports/nursing-and-primary-health-care-towards-realization-universal (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Tosam, M.J. Global Bioethics and Respect for Cultural Diversity: How Do We Avoid Moral Relativism and Moral Imperialism? Med. Health Care Philos. 2020, 23, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenkl, E.A.; Purnell, L.D. (Eds.) Handbook for Culturally Competent Care; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; ISBN 978-3-031-70491-8. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M.K.; Rosenkoetter, M.; Pacquiao, D.F.; Callister, L.C.; Hattar-Pollara, M.; Lauderdale, J.; Milstead, J.; Nardi, D.; Purnell, L. Guidelines for Implementing Culturally Competent Nursing Care. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2014, 25, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, M.; Paradies, Y.; Priest, N. Interventions to Improve Cultural Competency in Healthcare: A Systematic Review of Reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campinha-Bacote, J. The Process of Cultural Competence in the Delivery of Healthcare Services: A Model of Care. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2002, 13, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Tian, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, K.; Xiao, X.; Simoni, J.M.; Wang, H. The Influence of Cultural Competence of Nurses on Patient Satisfaction and the Mediating Effect of Patient Trust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jui-Chin, H.; Fen-Fang, C.; Tso-Ying, L.; Pao-Yu, W.; Mei-Hsiang, L. Exploring the Care Experiences of Hemodialysis Nurses: From the Cultural Sensitivity Approach. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihu, L.; Marques, R.M.D.; Pontifice Sousa, P. Strategies for Nursing Care of Critically Ill Multicultural Patients: A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 3468–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, K.; Job, S.; Blackwell, C.; Sanchez, K.; Carter, S.; Taliaferro, L. Provider Cultural Competence and Humility in Healthcare Interactions with Transgender and Nonbinary Young Adults. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2024, 56, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, J.R.; Corbett, J.; Bondaryk, M.R. Addressing Disparities and Achieving Equity: Cultural Competence, Ethics, and Health-Care Transformation. Chest 2014, 145, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurlark, R.S.; Akintade, B.; Broholm, C.; Clark, R.; Fyle-Thorpe, O.; Gatewood, E.; Graves, S.; Kuster, A.; Mihaly, L.; Mitchell, S.; et al. Advanced Practice Nursing Education: Strategies to Advance Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging. J. Nurs. Educ. 2025, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refugee and Migrant Health: Global Competency Standards for Health Workers, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-92-4-003062-6.

- Promoting the Health of Refugees and Migrants: Experiences from Around the World, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; ISBN 978-92-4-006711-0.

- McDermott-Levy, R.; Leffers, J.; Mayaka, J. Ethical Principles and Guidelines of Global Health Nursing Practice. Nurs. Outlook 2018, 66, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usberg, G.; Uibu, E.; Urban, R.; Kangasniemi, M. Ethical Conflicts in Nursing: An Interview Study. Nurs. Ethics 2021, 28, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarabi, A.A.; Alamri, A.A.; Jumah, S.A.; Aljohani, W.M.; Mohammed, A.; Badarb, A.M.B. The Impact of Cultural Beliefs on Medical Ethics and Patient Care. J. Healthc. Sci. 2024, 4, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naramore, R.; Marquez, E. A Choice Not to Choose: Respecting Patient Autonomy in Collectivist Cultures. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2024, 67, e636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, M.A.; Shaban, M.M.; Ramadan, O.M.E.; Zaky, M.E.; Mohammed, H.H.; Amer, F.G.M.; Shaban, M. Navigating End-of-Life Decision-Making in Nursing: A Systematic Review of Ethical Challenges and Palliative Care Practices. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linnard-Palmer, L.; Kools, S. Parents’ Refusal of Medical Treatment for Cultural or Religious Beliefs: An Ethnographic Study of Health Care Professionals’ Experiences. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2005, 22, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuberg, M.; Sopić, D.; Košanski, T.; Grabant, M.K.; Ribić, R.; Meštrović, T. Gender Bias and Perceptions of the Nursing Profession in Croatia: A Cross-Sectional Study Comparing Patients and the General Population. SAGE Open Nurs. 2024, 10, 23779608241271653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodosopoulos, L.; Fradelos, E.C.; Panagiotou, A.; Dreliozi, A.; Tzavella, F. Delivering Culturally Competent Care to Migrants by Healthcare Personnel: A Crucial Aspect of Delivering Culturally Sensitive Care. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, P.P. Patient Advocacy: The Role of the Nurse. Nurs. Stand. 2015, 29, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markey, K. Moral Reasoning as a Catalyst for Cultural Competence and Culturally Responsive Care. Nurs. Philos. 2021, 22, e12337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann, E.H.; Tallman, B.A. The Impact of Nurses’ Beliefs, Attitudes, and Cultural Sensitivity on the Management of Patient Pain. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2022, 33, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, D.; Koreik, U.; Ohm, U.; Riemer, C.; Rahe-Meyer, N. Informed Consent at Stake? Language Barriers in Medical Interactions with Immigrant Anaesthetists: A Conversation Analytical Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelin, J.R.; Siraj, D.S.; Victor, R.; Kotadia, S.; Maldonado, Y.A. The Impact of Unconscious Bias in Healthcare: How to Recognize and Mitigate It. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 220, S62–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarafis, P.; Michael, I.; Chara, T.; Maria, M. Reliability and Validity of the Transcultural Self-Efficacy Tool Questionnaire (Greek Version). J. Nurs. Meas. 2014, 22, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffreys, M.R.; Smodlaka, I. Steps of the Instrument Design Process: An Illustrative Approach for Nurse Educators. Nurse Educ. 1996, 21, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffreys, M.R.; Smodlaka, I. Exploring the Factorial Composition of the Transcultural Self-Efficacy Tool. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 1998, 35, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffreys, M.R. Development and Psychometric Evaluation of the Transcultural Self-Efficacy Tool: A Synthesis of Findings. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2000, 11, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffreys, M.R. The Cultural Competence Education Resource Toolkit; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Toska, A.; Latsou, D.; Saridi, M.; Sarafis, P.; Souliotis, K. The Validity and Reliability of a Questionnaire on the Knowledge and Attitudes of Nurses about Ethics. Available online: https://ir.lib.uth.gr/xmlui/handle/11615/79733?show=full (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Hariharan, S.; Jonnalagadda, R.; Walrond, E.; Moseley, H. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice of Healthcare Ethics and Law among Doctors and Nurses in Barbados. BMC Med. Ethics 2006, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. On the Functional Properties of Perceived Self-Efficacy Revisited. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 9–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, I. The Papadopoulos, Tilki and Taylor Model of Developing Cultural Competence. In Transcultural Health and Social Care: Development of Culturally Competent Practitioners; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kaihlanen, A.-M.; Hietapakka, L.; Heponiemi, T. Increasing Cultural Awareness: Qualitative Study of Nurses’ Perceptions about Cultural Competence Training. BMC Nurs. 2019, 18, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Moral, J.M.; Tosun, B.; Gómez-Ibáñez, R.; Navarrete, L.; Yava, A.; Aguayo-González, M.; Dirgar, E.; Checa-Jiménez, C.; Bernabeu-Tamayo, M.D. From a Learning Opportunity to a Conscious Multidimensional Change: A Metasynthesis of Transcultural Learning Experiences among Nursing Students. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffreys, M.R. Teaching Cultural Competence in Nursing and Health Care: Inquiry, Action, and Innovation; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Osmancevic, S.; Großschädl, F.; Lohrmann, C. Cultural Competence among Nursing Students and Nurses Working in Acute Care Settings: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farokhzadian, J.; Nematollahi, M.; Dehghan Nayeri, N.; Faramarzpour, M. Using a Model to Design, Implement, and Evaluate a Training Program for Improving Cultural Competence among Undergraduate Nursing Students: A Mixed Methods Study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Mohlia, A.; Kukreti, P.; Saurabh; Kataria, D. Sexual and Gender Minority Health Care Issues Related Competence and Preparedness Among the Health Care Professionals and Trainees in India: A Comparative Study. J. Psychosexual Health 2024, 6, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Basit, G.; Demirören, N.; Alabay, K.N.K. Impact of Ethics Education on Nursing Students’ Ethical Sensitivity and Patient Advocacy: A Quasi-Experimental Study. J. Acad. Ethics 2024, 23, 1107–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, I.; Inagaki, S.; Osawa, A.; Umeda, S.; Hanafusa, Y.; Morita, S.; Maruyama, H. Effects of an Ethics Education Program on Nurses’ Moral Efficacy in an Acute Health Care Facility. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 2207–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliken, A.; Grace, P. Nurse Ethical Awareness: Understanding the Nature of Everyday Practice. Nurs. Ethics 2017, 24, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotrotsiou, S.; Stathopoulou, A.; Theofanidis, D.; Katsiana, A.; Paralikas, T. Investigation of Cultural Competence in Greek Nursing Students. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2020, 13, 1898. [Google Scholar]

- Ünsal, B.; Özbudak Arıca, E.; Höbek Akarsu, R. Ethical Issues after the Earthquake in Turkey: A Qualitative Study on Nurses’ Perspectives. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2024, 72, e13048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Choi, S. Factors Influencing Patient-Centeredness among Korean Nursing Students: Empathy and Communication Self-Efficacy. Healthcare 2021, 9, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawutschke, R.; Pastrana, T.; Schmitz, D. Conscientious Objection and Barriers to Abortion within a Specific Regional Context—An Expert Interview Study. BMC Med. Ethics 2024, 25, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarda-Rodrigues, J.; Dias, M.P.F.C.; Fatela, M.M.R.; Jeremias, C.J.R.; Negreiro, M.P.G.; e Sousa, O.L. Culturally Competent Nursing Care as a Promoter of Parental Empowerment in Neonatal Unit: A Scoping Review. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2025, 31, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The ICN Code of Ethics for Nurses. Available online: https://www.icn.ch/resources/publications-and-reports/icn-code-ethics-nurses (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Dörmann, L.; Nauck, F.; Wolf-Ostermann, K.; Stanze, H. “I Should at Least Have the Feeling That It […] Really Comes from Within”: Professional Nursing Views on Assisted Suicide. Palliat. Med. Rep. 2023, 4, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhihi, E.A.; Aljarary, K.L.; Alahmadi, M.; Adam, J.B.; Almwualllad, O.A.; Hawsawei, M.S.; Hamza, A.A.; Ibrahim, I.A. The Mediating Role of Moral Courage in the Relationship between Ethical Leadership and Error Reporting Behavior among Nurses in Saudi Arabia: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, S.; Horne, M.; Hills, R.; Kendall, E. Cultural Competence in Healthcare in the Community: A Concept Analysis. Health Soc. Care Community 2018, 26, 590–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, L.; Adetayo, O.A. Cultural Competence and Ethnic Diversity in Healthcare. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2019, 7, e2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koskenvuori, J.; Stolt, M.; Suhonen, R.; Leino-Kilpi, H. Healthcare Professionals’ Ethical Competence: A Scoping Review. Nurs. Open 2018, 6, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersson, M.; Hedström, M.; Höglund, A.T. Ethical Competence in Dnr Decisions—A Qualitative Study of Swedish Physicians and Nurses Working in Hematology and Oncology Care. BMC Med. Ethics 2018, 19, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandemir, D.; Yüksel, S. Professional Values, Cultural Competence, and Moral Sensitivity of Surgical Nurses: Mediation Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling. Nurs. Ethics 2024, 32, 1253–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Socio-Demographic and Professional Variables | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 55 | 11.3% |

| Female | 433 | 88.7% | |

| Age (years) | Mean/Standard Deviation (SD) | 42.2 | 9.7 |

| Marital Status | Single | 127 | 25.9% |

| Married | 293 | 59.8% | |

| In civil partnership | 25 | 5.1% | |

| Divorced | 39 | 8.0% | |

| Widowed | 6 | 1.2% | |

| Education Level | Two-year program | 110 | 22.4% |

| TEI degree | 199 | 40.4% | |

| AEI degree | 50 | 10.2% | |

| Master’s (MSc) | 129 | 26.2% | |

| Doctorate (PhD) | 4 | 0.8% | |

| Work Unit Location | Mainland | 313 | 63.6% |

| Island-based | 179 | 36.4% | |

| Years of Experience | Mean/Standard Deviation (SD) | 16.0 | 9.9 |

| Presence of Migrant Reception or Closed Controlled Center | Yes | 89 | 18.1% |

| No | 403 | 81.9% | |

| Subscale | Mean | SD | Median | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | 7.2 | 1.6 | 7.4 | 1.8 | 10 |

| Practical | 6.9 | 1.5 | 7.0 | 2.8 | 10 |

| Affective | 7.4 | 1.3 | 7.4 | 2.8 | 10 |

| Practical Self-Efficacy | Affective Self-Efficacy | Ethical Attitudes | Ethical Knowledge | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson’s r | p-Value | Pearson’s r | p-Value | Pearson’s r | p-Value | Pearson’s r | p-Value | |

| Cognitive Self-Efficacy | 0.59 | <0.001 | 0.47 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.54 | 0.19 | <0.001 |

| Practical Self-Efficacy | 0.67 | <0.001 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.17 | <0.001 | ||

| Affective Self-Efficacy | 0.23 | <0.001 | 0.27 | <0.001 | ||||

| Ethical Attitudes | 0.19 | <0.001 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Theodosopoulos, L.; Fradelos, E.C.; Panagiotou, A.; Tzavella, F. Cultural Competence and Ethics Among Nurses in Primary Healthcare: Exploring Their Interrelationship and Implications for Care Delivery. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2117. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172117

Theodosopoulos L, Fradelos EC, Panagiotou A, Tzavella F. Cultural Competence and Ethics Among Nurses in Primary Healthcare: Exploring Their Interrelationship and Implications for Care Delivery. Healthcare. 2025; 13(17):2117. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172117

Chicago/Turabian StyleTheodosopoulos, Lampros, Evangelos C. Fradelos, Aspasia Panagiotou, and Foteini Tzavella. 2025. "Cultural Competence and Ethics Among Nurses in Primary Healthcare: Exploring Their Interrelationship and Implications for Care Delivery" Healthcare 13, no. 17: 2117. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172117

APA StyleTheodosopoulos, L., Fradelos, E. C., Panagiotou, A., & Tzavella, F. (2025). Cultural Competence and Ethics Among Nurses in Primary Healthcare: Exploring Their Interrelationship and Implications for Care Delivery. Healthcare, 13(17), 2117. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172117