Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Needs in the Association Between Exercise Goal Content and Subjective Well-Being in Portuguese Older Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Statistical Analysis

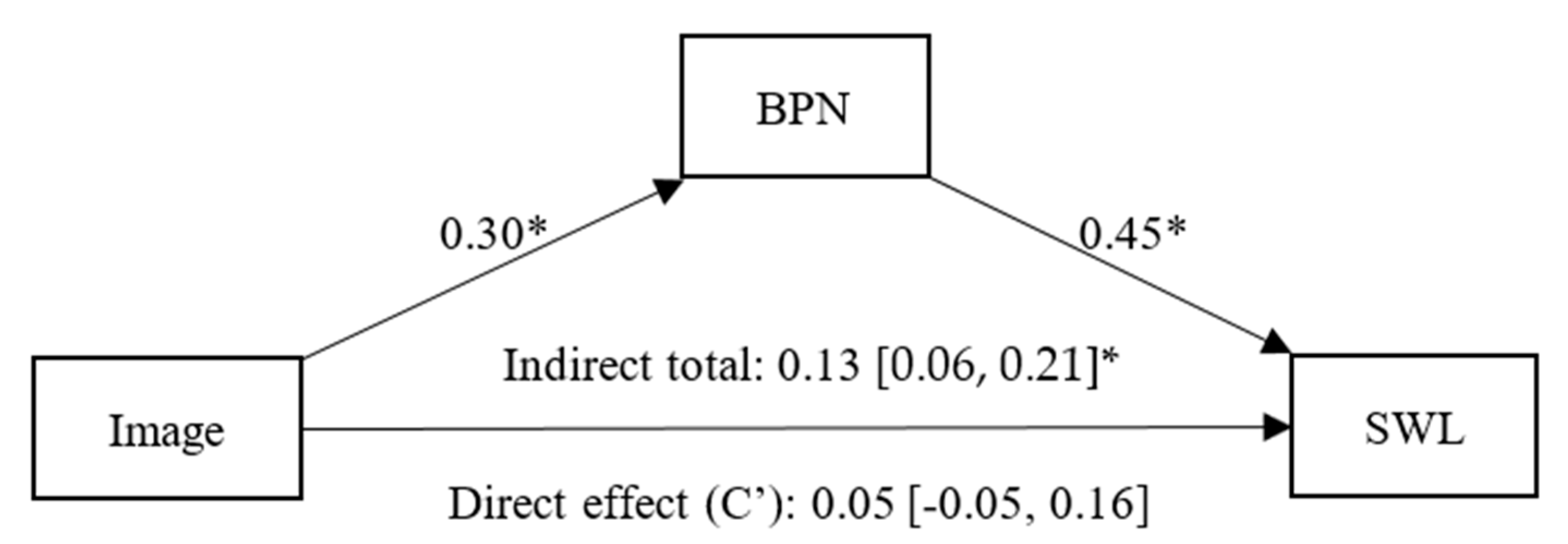

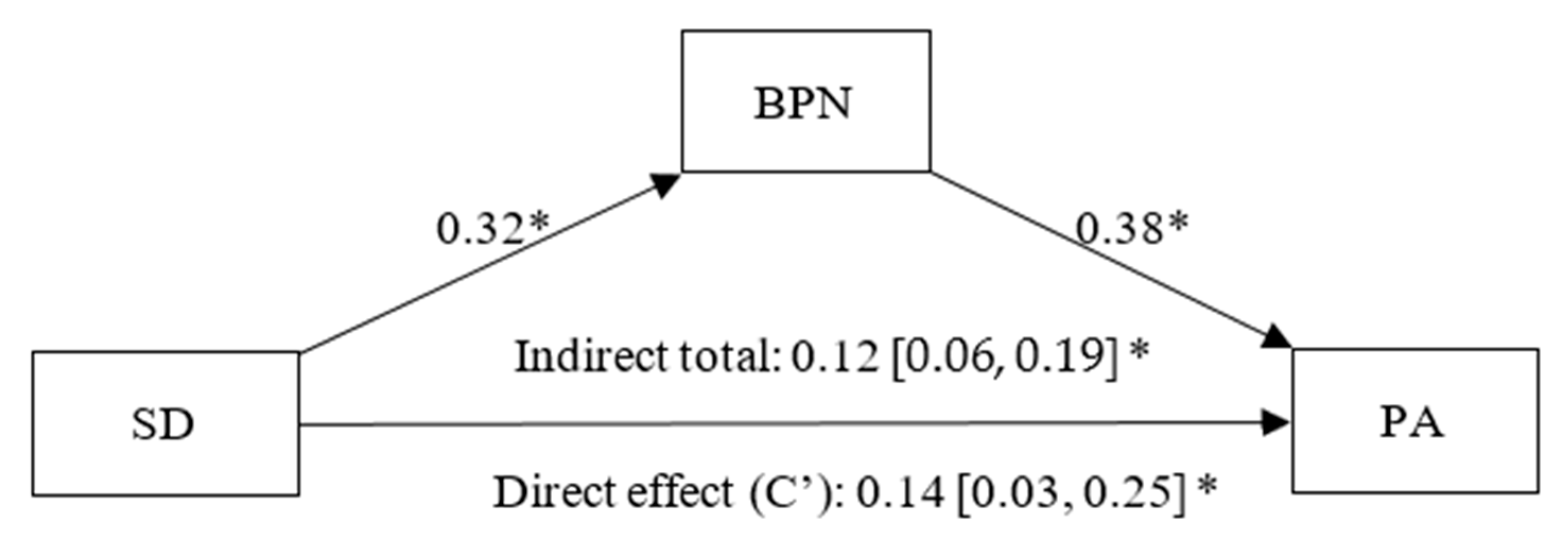

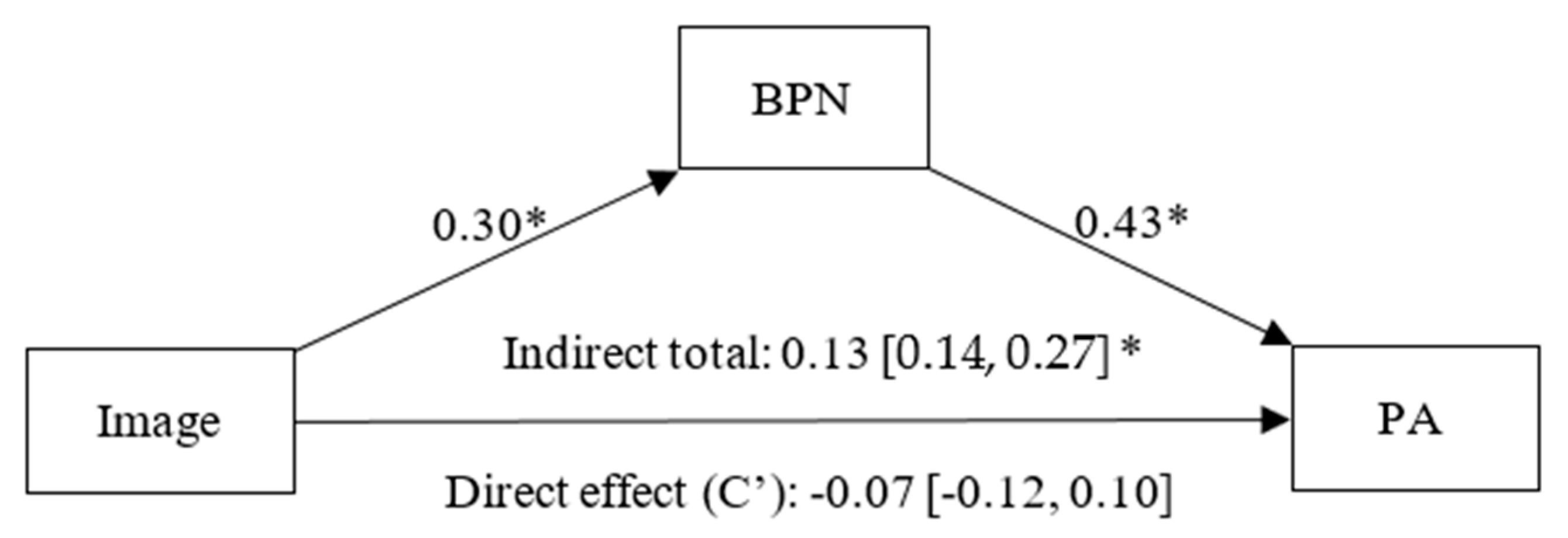

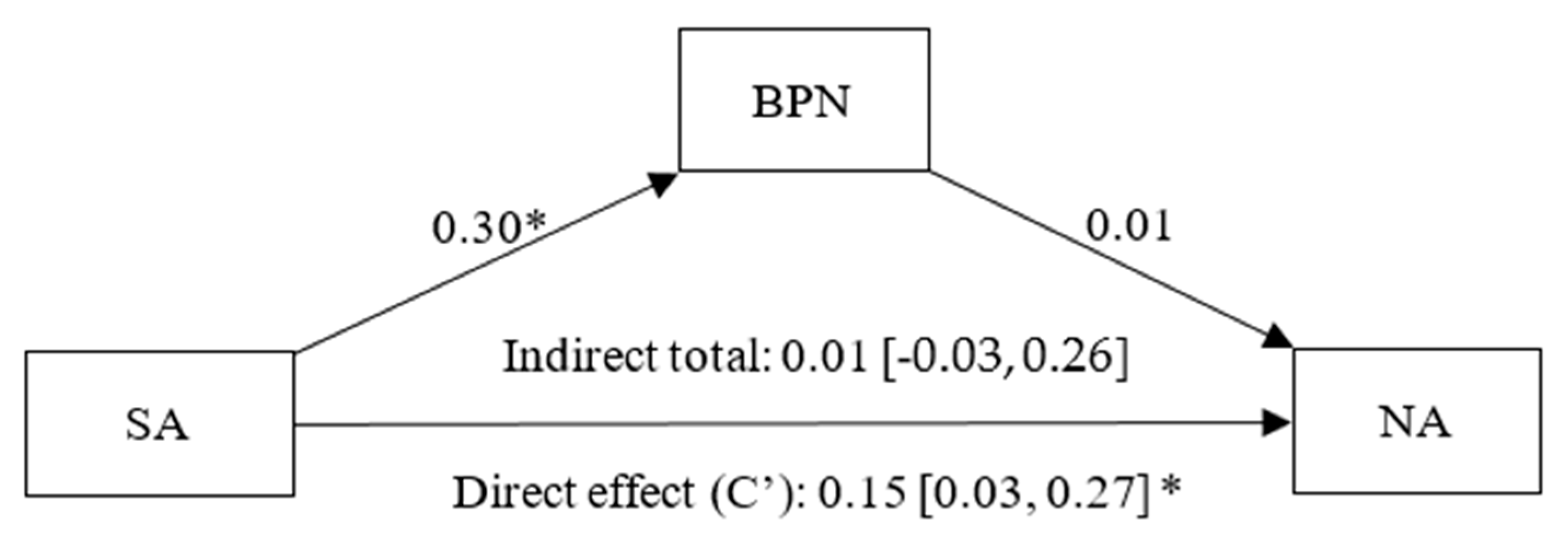

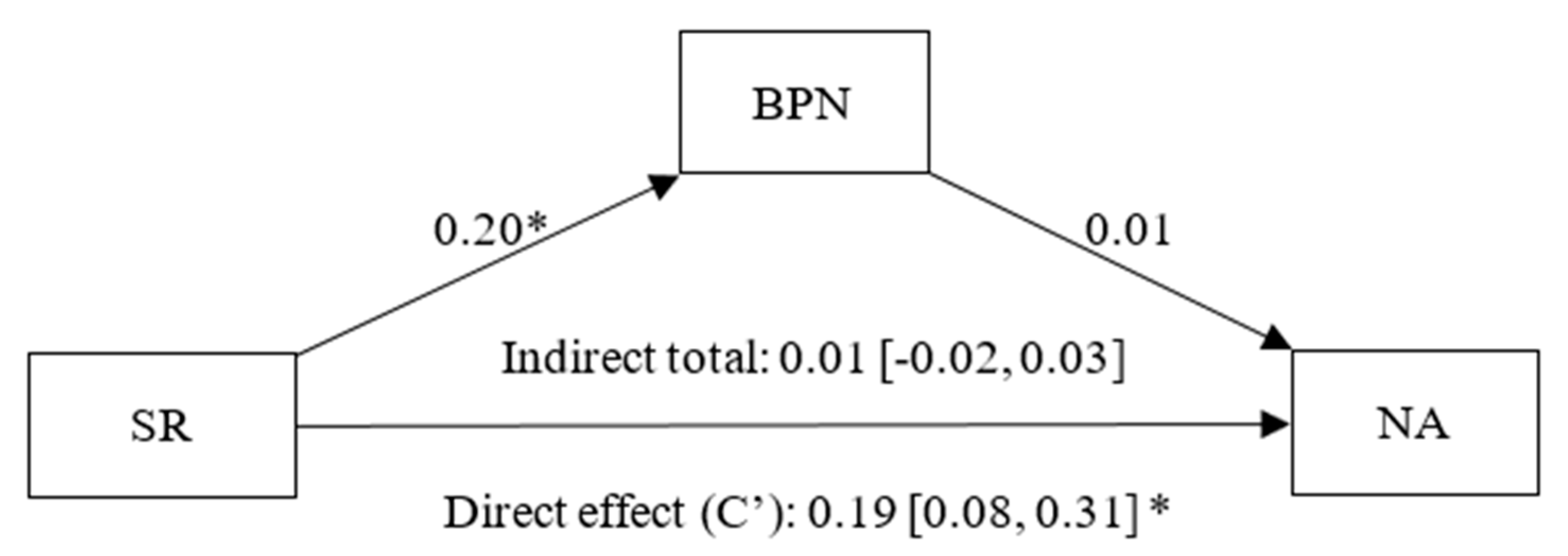

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Social Report 2023: Leaving No One Behind in an Ageing World; World Social Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-92-1-001968-2. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- European Commission. 2024 Ageing Report: Economic & Budgetary Projections for the EU Member States (2022–2070); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. World Report on Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565042 (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Newman-Norlund, R.D.; Newman-Norlund, S.E.; Sayers, S.; McLain, A.C.; Riccardi, N.; Fridriksson, J. Effects of Social Isolation on Quality of Life in Elderly Adults. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Deaton, A.; Stone, A.A. Subjective Wellbeing, Health, and Ageing. Lancet 2015, 385, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Chan, M.Y. Happy People Live Longer: Subjective Well-Being Contributes to Health and Longevity. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2011, 3, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Investing in Mental Health: Evidence for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; ISBN 978-92-4-156461-8. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ballesteros, R. Active Aging: The Contribution of Psychology; Hogrefe & Huber Publishers: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-88937-360-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog, C.; Kramer, A.F.; Wilson, R.S.; Lindenberger, U. Enrichment Effects on Adult Cognitive Development: Can the Functional Capacity of Older Adults Be Preserved and Enhanced? Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2008, 9, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, W.; Ik Suh, Y.; Ryu, J.; Heo, J. Physical Activity Levels and Well-Being in Older Adults. Psychol. Rep. 2017, 120, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antunes, R.; Couto, N.; Vitorino, A.; Monteiro, D.; Marinho, D.A.; Cid, L. Physical Activity and Affect of the Elderly: Contribution to the Validation of the Positive and Negative Affect Shedule (PANAS) in the Portuguese Population. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2020, 15, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. European Union Special Eurobarometer 525: Sport and Physical Activity; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hallal, P.C.; Andersen, L.B.; Bull, F.C.; Guthold, R.; Haskell, W.; Ekelund, U.; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Global Physical Activity Levels: Surveillance Progress, Pitfalls, and Prospects. Lancet 2012, 380, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Norman, I.J.; While, A.E. Physical Activity in Older People: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosil, J. Psicología de la Actividad Física Y del Deporte; McGraw-Hill Interamericana de España S.L.: Madrid, Spain, 2008; ISBN 978-84-481-6103-3. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, R. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Sebire, S.; Standage, M.; Vansteenkiste, M. Development and Validation of the Goal Content for Exercise Questionnaire. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2008, 30, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.; Deci, E. Overview of Self-Determination Theory: An Organismic-Dialectical Perspective. In Handbook of Self-Determination Research; University of Rochester Press: Rochester, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 3–33. ISBN 978-1-58046-108-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.; Deci, E. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4625-3896-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.; Deci, E. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, R. Self-Determination Theory: A Macrotheory of Human Motivation, Development, and Health. Can. Psychol./Psychol. Can. 2008, 49, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Sierens, E.; Soenens, B.; Luyckx, K.; Lens, W. Motivational Profiles from a Self-Determination Perspective: The Quality of Motivation Matters. J. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 101, 671–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.N.; Vieira, P.N.; Coutinho, S.R.; Minderico, C.S.; Matos, M.G.; Sardinha, L.B.; Teixeira, P.J. Using Self-Determination Theory to Promote Physical Activity and Weight Control: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Women. J. Behav. Med. 2010, 33, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, F.; Jacinto, M.; Couto, N.; Monteiro, D.; Monteiro, A.M.; Forte, P.; Antunes, R. Motivational Correlates, Satisfaction with Life, and Physical Activity in Older Adults: A Structural Equation Analysis. Medicina 2023, 59, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, R. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebire, S.J.; Standage, M.; Vansteenkiste, M. Examining Intrinsic versus Extrinsic Exercise Goals: Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Outcomes. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2009, 31, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebire, S.J.; Standage, M.; Vansteenkiste, M. Predicting Objectively Assessed Physical Activity from the Content and Regulation of Exercise Goals: Evidence for a Mediational Model. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2011, 33, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Niemiec, C.P.; Soenens, B. The Development of the Five Mini-Theories of Self-Determination Theory: An Historical Overview, Emerging Trends, and Future Directions. In The Decade Ahead: Theoretical Perspectives on Motivation and Achievement; Emerald: Leeds, UK, 2010; Volume 16A, pp. 105–166. ISBN 978-0-85724-111-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ingledew, D.K.; Markland, D. The Role of Motives in Exercise Participation. Psychol. Health 2008, 23, 807–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Carraça, E.V.; Markland, D.; Silva, M.N.; Ryan, R.M. Exercise, Physical Activity, and Self-Determination Theory: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, R.; Couto, N.; Monteiro, D.; Moutao, J.; Marinho, D.; Cid, L. Goal Content for the Practice of Physical Activity. J. Aging Sci. 2018, 6, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M. The Role of Autonomy Support and Autonomy Orientation in Prosocial Behavior Engagement. Motiv. Emot. 2003, 27, 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, N.; Antunes, R.; Monteiro, D.; Moutão, J.; Marinho, D.A.; Cid, L. Basic Psychological Needs and Subjective Well-Being in Portuguese Older People. Ann. Psychol. 2020, 36, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect: The PANAS Scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antunes, R.; Couto, N.; Vitorino, A.; Monteiro, D.; Moutão, J.; Marinho, D.; Cid, L. Physical Activity and Satisfaction with the Life of the Elderly: Contribution to the Validation of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Swls) in the Portuguese Population. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Ejerc. Y El Deporte 2019, 14, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, Conditional, and Moderated Moderated Mediation: Quantification, Inference, and Interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. xvii, 534. ISBN 978-1-4625-2334-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, M.S.; MacKinnon, D.P. Required Sample Size to Detect the Mediated Effect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, D. A Single Factor Test of Common Method Variance. J. Psychol. 1967, 35, 359–378. [Google Scholar]

- Baert, V.; Gorus, E.; Mets, T.; Geerts, C.; Bautmans, I. Motivators and Barriers for Physical Activity in the Oldest Old: A Systematic Review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2011, 10, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Turan, B.; Scheibe, S.; Ram, N.; Ersner-Hershfield, H.; Samanez-Larkin, G.R.; Brooks, K.P.; Nesselroade, J.R. Emotional Experience Improves with Age: Evidence Based on over 10 Years of Experience Sampling. Psychol. Aging 2011, 26, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective Well-Being: Three Decades of Progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, P.; McGaw, B.; Care, E. (Eds.) Assessment and Teaching of 21st Century Skills; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; ISBN 978-94-007-2323-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hagger, M.; Chatzisarantis, N. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Exercise and Sport; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-7360-6250-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Napa Scollon, C.; Lucas, R.E. The Evolving Concept of Subjective Well-Being: The Multifaceted Nature of Happiness. In Advances in Cell Aging and Gerontology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 15, pp. 187–219. ISBN 978-0-444-51495-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt, K.S.d.A.; Santos, S.S.C. Quality of Life in Old Age: Multidisciplinary Approach. Rev. Enferm. UFPE Line 2010, 4, 451–452. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, R.E. Adaptation and the Set-Point Model of Subjective Well-Being: Does Happiness Change After Major Life Events? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 16, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavot, W.; Diener, E. The Satisfaction With Life Scale and the Emerging Construct of Life Satisfaction. J. Posit. Psychol. 2008, 3, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasser, T.; Ryan, R.M. Further Examining the American Dream: Differential Correlates of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Goals. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 22, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M.; Lynch, J.E. Body Image across the Life Span in Adult Women: The Role of Self-Objectification. Dev. Psychol. 2001, 37, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B. Stereotype Embodiment: A Psychosocial Approach to Aging. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assor, A.; Roth, G.; Deci, E.L. The Emotional Costs of Parents’ Conditional Regard: A Self-Determination Theory Analysis. J. Personal. 2004, 72, 47–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Niemiec, C.P. It’s Not Just the Amount That Counts: Balanced Need Satisfaction Also Affects Well-Being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Seligman, M.E.P. Very Happy People. Psychol. Sci. 2002, 13, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Huta, V.; Deci, E.L. Living Well: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective on Eudaimonia. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 139–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hiel, A.; Vansteenkiste, M. Ambitions Fulfilled? The Effects of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Goal Attainment on Older Adults’ Ego-Integrity and Death Attitudes. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2009, 68, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garn, A.C.; Wallhead, T. Social Goals and Basic Psychological Needs in High School Physical Education. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2015, 4, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, D.N.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Beyond Talk: Creating Autonomous Motivation through Self-Determination Theory. J. Gen. Manag. 2009, 34, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, J.; Ntoumanis, N.; Duda, J.L. A Test of Self-Determination Theory in the Exercise Domain. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 36, 2240–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—Health Management | - | ||||||||

| 2—Skill Development | 0.48 ** | - | |||||||

| 3—Image | 0.45 ** | 0.56 ** | - | ||||||

| 4—Social Recognition | 0.45 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.56 ** | - | |||||

| 5—Social Affiliation | 0.39 ** | 0.67 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.64 ** | - | ||||

| 6—BPNs | 0.45 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.30 ** | - | |||

| 7—PA | 0.28 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.12 * | −0.02 | 0.12 * | 0.43 ** | - | ||

| 8—NA | 0.57 | 0.10 | 0.17 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.53 | 0.41 | - | |

| 9—SWL | 0.22 ** | 0.96 | 0.18 ** | 0.71 | 0.33 | 0.46 ** | 0.28 ** | −0.27 ** | - |

| Mean | 6.01 | 5.06 | 4.93 | 3.80 | 4.88 | 5.42 | 3.28 | 1.93 | 4.71 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.79 | 1.14 | 1.10 | 1.38 | 1.14 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.71 | 1.00 |

| Skewness | −0.84 | −0.80 | −0.76 | −0.18 | −0.86 | −0.90 | −1.41 | 0.98 | −0.25 |

| Kurtosis | 1.14 | 1.60 | 1.77 | −0.31 | 1.54 | 0.86 | 0.07 | 1.08 | 0.37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Couto, N.; Antunes, R.; Bento, T.; Vitorino, A.; Monteiro, D.; Cid, L. Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Needs in the Association Between Exercise Goal Content and Subjective Well-Being in Portuguese Older Adults. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2086. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172086

Couto N, Antunes R, Bento T, Vitorino A, Monteiro D, Cid L. Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Needs in the Association Between Exercise Goal Content and Subjective Well-Being in Portuguese Older Adults. Healthcare. 2025; 13(17):2086. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172086

Chicago/Turabian StyleCouto, Nuno, Raul Antunes, Teresa Bento, Anabela Vitorino, Diogo Monteiro, and Luís Cid. 2025. "Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Needs in the Association Between Exercise Goal Content and Subjective Well-Being in Portuguese Older Adults" Healthcare 13, no. 17: 2086. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172086

APA StyleCouto, N., Antunes, R., Bento, T., Vitorino, A., Monteiro, D., & Cid, L. (2025). Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Needs in the Association Between Exercise Goal Content and Subjective Well-Being in Portuguese Older Adults. Healthcare, 13(17), 2086. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172086