Effects of Tibetan Singing Bowl Intervention on Psychological and Physiological Health in Adults: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Management

2.4. Quality Assessment Tools

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Screening Results

3.2. Characteristics of Studies

3.3. Intervention Methods, Duration, and Control Designs of Included Studies

3.4. Measurement Tools

3.5. Effects of the Interventions

3.5.1. Psychological Indicator: Anxiety

3.5.2. Psychological Indicator: Depressive Symptoms

3.5.3. Psychological Indicator: Stress

3.5.4. Psychological Indicator: Well-Being

3.5.5. Psychological Indicator: Quality of Life

3.5.6. Physiological Indicator: Heart Rate Variability (HRV)

3.5.7. Physiological Indicator: Heart Rate-Related Variables

3.5.8. Physiological Indicator: Brainwave Activity

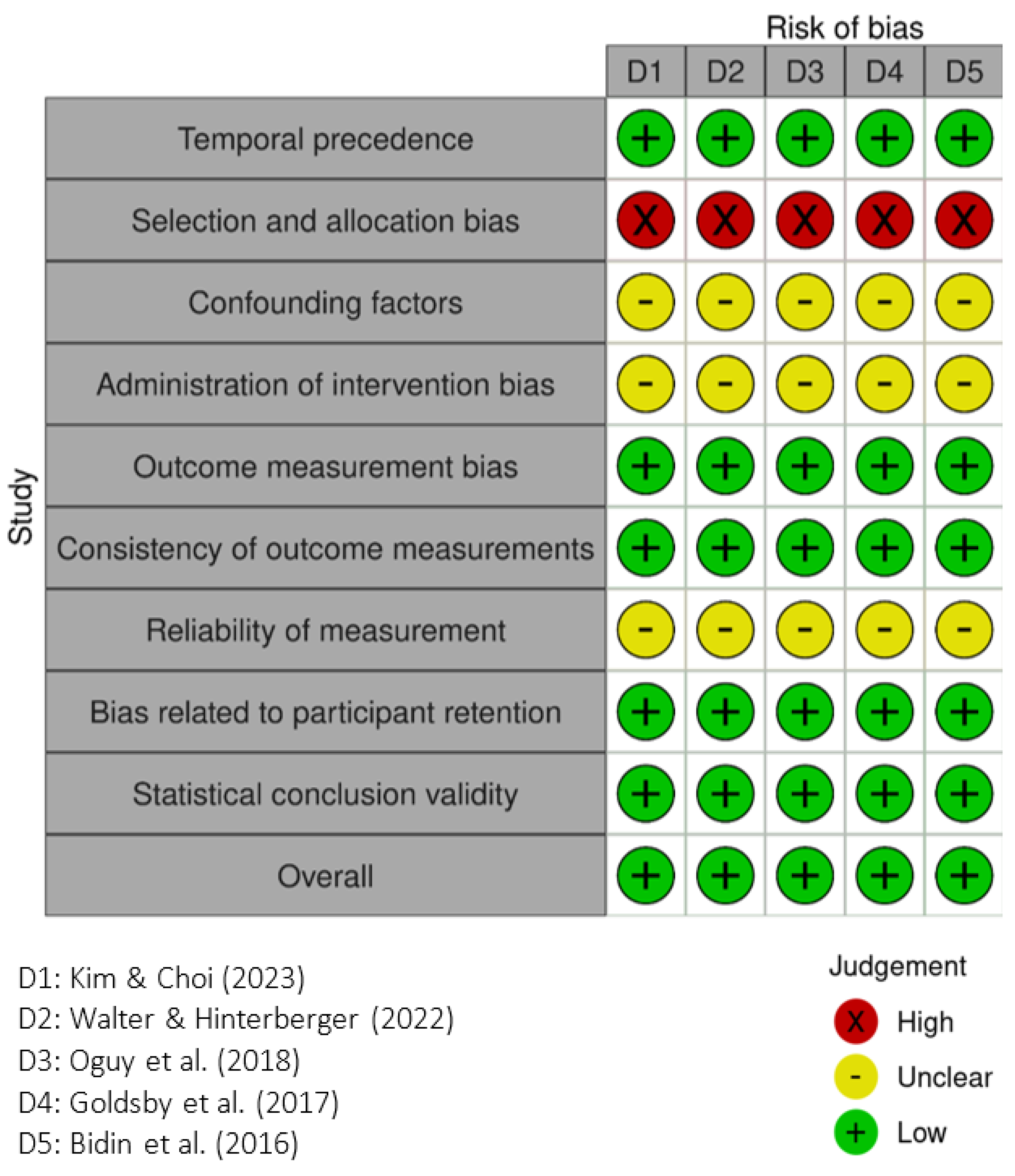

3.6. Quality Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Osborne, M.T.; Shin, L.M.; Mehta, N.N.; Pitman, R.K.; Fayad, Z.A.; Tawakol, A. Disentangling the links between psychosocial stress and cardiovascular disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 13, e010931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santosa, A.; Rosengren, A.; Ramasundarahettige, C.; Rangarajan, S.; Gulec, S.; Chifamba, J.; Lear, S.A.; Poirier, P.; Yeates, K.E.; Yusuf, R. Psychosocial risk factors and cardiovascular disease and death in a population-based cohort from 21 low-, middle-, and high-income countries. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2138920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remes, O.; Brayne, C.; Van Der Linde, R.; Lafortune, L. A systematic review of reviews on the prevalence of anxiety disorders in adult populations. Brain Behav. 2016, 6, e00497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, N.; Klein, J.D. Mental health and non-communicable diseases: A narrative review. Pediatr. Med. 2021, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandelow, B.; Boerner, R.; Kasper, S.; Linden, M.; Wittchen, H.-U.; Möller, H.-J. The diagnosis and treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt Int. 2013, 110, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.G.; Asnaani, A.; Vonk, I.J.; Sawyer, A.T.; Fang, A. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2012, 36, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazdin, A.E. Addressing the treatment gap: A key challenge for extending evidence-based psychosocial interventions. Behav. Res. Ther. 2017, 88, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, J.M. Physiological and psychological effects of a Himalayan singing bowl in meditation practice: A quantitative analysis. Am. J. Health Promot. 2014, 28, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsby, T.L.; Goldsby, M.E.; McWalters, M.; Mills, P.J. Effects of singing bowl sound meditation on mood, tension, and well-being: An observational study. J. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 22, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, Z.; Mohammadi, S.; Karimi, H. Investigating the Effect of Singing Bowl Sound on the Level of State-trait Anxiety and Physiological Variables of Patients Awaiting Angiography. J. Perianesth. Nurs. 2025, 40, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, M.; Riedinger, S.; Stefani, A.; Mitterling, T.; Holzknecht, E.; Grassmayr, P.; Högl, B. Effects of singing bowl exposure on Karolinska sleepiness scale and pupillographic sleepiness test: A randomised crossover study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelsch, S.; Fritz, T.; v. Cramon, D.Y.; Müller, K.; Friederici, A.D. Investigating emotion with music: An fMRI study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2006, 27, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanduri, C.; Raijas, P.; Ahvenainen, M.; Philips, A.K.; Ukkola-Vuoti, L.; Lähdesmäki, H.; Järvelä, I. The effect of listening to music on human transcriptome. PeerJ 2015, 3, e830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janata, P. The neural architecture of music-evoked autobiographical memories. Cereb. Cortex 2009, 19, 2579–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nozaradan, S. Exploring how musical rhythm entrains brain activity with electroencephalogram frequency-tagging. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, S.-G.; Bae, M.-J. Analysis of health-healing effects according to acoustic signal characteristics in psychoacoustic. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2019, 12, 2057–2060. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsby, T.L.; Goldsby, M.E.; McWalters, M.; Mills, P.J. Sound healing: Mood, emotional, and spiritual well-being interrelationships. Religions 2022, 13, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, N.; Hinterberger, T. Neurophysiological effects of a singing bowl massage. Medicina 2022, 58, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidin, L.; Pigaiani, L.; Casini, M.; Seghini, P.; Cavanna, L. Feasibility of a trial with Tibetan Singing Bowls, and suggested benefits in metastatic cancer patients. A pilot study in an Italian Oncology Unit. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2016, 8, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-C.; Choi, M.-J. Does the Sound of a Singing Bowl Synchronize Meditational Brainwaves in the Listeners? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetharaman, R.; Avhad, S.; Rane, J. Exploring the healing power of singing bowls: An overview of key findings and potential benefits. Explore 2024, 20, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanhope, J.; Weinstein, P. The human health effects of singing bowls: A systematic review. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 51, 102412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufanaru, C.; Munn, Z.; Aromataris, E.; Campbell, J.; Hopp, L. Chapter 3: Systematic Reviews of Effectiveness. Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/355827955 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Barker, T.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Stern, C.; Aromataris, E. JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Rio-Alamos, C.; Montefusco-Siegmund, R.; Cañete, T.; Sotomayor, J.; Fernandez-Teruel, A. Acute relaxation response induced by tibetan singing bowl sounds: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamou, V.; Chatzoudi, T.; Stamou, L.; Romo, L.; Graziani, P. Music-assisted systematic desensitization for the reduction of craving in response to drug-conditioned cues: A pilot study. Arts Psychother. 2016, 51, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wepner, F.; Hahne, J.; Teichmann, A.; Berka-Schmid, G.; Hördinger, A.; Friedrich, M. Quarzklangschalentherapie bei Wirbelsäulenbeschwerden und chronobiologische Vorgänge–eine randomisierte kontrollierte Studie. Forsch. Komplementärmedizin/Res. Complement. Med. 2008, 15, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozmogova, N.; Bohdanovska, N.; Boichenko, C.; Mashir, V.; Rudenko, A. The influence of the complex program of psychophysiological audio-vibrovisualization with Tibetan bowls on the level of psychological well-being of Ukrainian refugees. Phytother. J. 2023, 4, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguy, V.O.; Bykov, E.; Litvichenko, E. Single vibroacoustic impact effect of singing bowls over the psycho-emotional state and cardiovascular system work. J. Intellect. Disabil. Diagn. Treat 2021, 9, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, G.Y.; Saboo, B. A comparative study of the impact of Himalayan singing bowls and supine silence on stress index and heart rate variability. J. Behav. Ther. Ment. Health 2019, 2, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguy, V.O.; Svirshch, E.N.; Tarasenko, A.A. Study of vibroacoustic tibetan massage effectiveness to reduce anxiety level. Mod. Eur. Res. 2018, 2, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Klimesch, W. EEG alpha and theta oscillations reflect cognitive and memory performance: A review and analysis. Brain Res. Rev. 1999, 29, 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahn, B.R.; Polich, J. Meditation states and traits: EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagopoulos, J.; Xu, J.; Rasmussen, I.; Vik, A.; Malhi, G.S.; Eliassen, C.F.; Arntsen, I.E.; Sæther, J.G.; Hollup, S.; Holen, A. Increased theta and alpha EEG activity during nondirective meditation. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2009, 15, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szentirmai, E.; Yasuda, T.; Taishi, P.; Wang, M.; Churchill, L.; Bohnet, S.; Magrath, P.; Kacsóh, B.; Jimenez, L.; Krueger, J.M. Growth hormone-releasing hormone: Cerebral cortical sleep-related EEG actions and expression. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2007, 293, R922–R930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella-Soler, V.; Valderrama, M.; Crepon, B.; Navarro, V.; Le Van Quyen, M. Large-scale cortical dynamics of sleep slow waves. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaut, M.H.M.; McIntosh, G.C. How Music Helps to Heal the Injured Brain: Therapeutic Use Crescendos Thanks to Advances in Brain Science. Cerebrum . March 2010. Available online: https://www.muzikoterapeuti.hr/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/How-music-helps-to-heal.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Porges, S. The polyvagal perspective. Biol. Psychol. 2007, 74, 116–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors (Year) Country | Participants | Sample Size and Age: M ± SD | Intervention | Comparison | Outcome Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rio-Alamos et al. (2023) [25] Chile | 50 adults with anxiety | TSB (n = 16), age: 26.2 ± 1.5. PMR (n = 19), age: 26.3 ± 1.0. CWL (n = 15), age: 25.9 ± 1.0. | One 50 min session with four Tibetan bowls, struck and rubbed to produce sound | PMR group performed muscle tensing and relaxing from feet to head for 50 min with audio guidance. CWL group sat quietly without doing anything. | SAI, HRV, EEG | TSB showed greater reductions in anxiety and EEG alpha power, and increases in HRV (HF), compared to PMR and CWL after a single session (p < 0.001). |

| Bergmann et al. (2020) [11] Austria | 48 healthy adults | Median age: 31.3 Age range: 20–59 | One session lying in a hammock over a 176 cm bowl, struck seven times, followed by relaxation | Silent Bowl group lay in a hammock above the bowl for 20 min without sound. | KSS, rPUI | TSB significantly reduced subjective sleepiness (p = 0.041), especially in women; no significant effect on objective sleepiness (p = 0.460). |

| Stamou et al. (2016) [26] Greece | 24 adults in treatment for heroin addiction | IMT (n = 8), NIMT (n = 8), Control (n = 8). Age: 32.58 ± 5.79 | Six sessions over 3 weeks: 20 min live Tibetan bowl music + 50 min guided imagery (IMT) | IMT group received singing bowl music with guided imagery twice a week for six sessions. NIMT group received recorded relaxing music with guided imagery twice a week for six sessions. | Cue-induced craving, CRS, ICT, SCL-90-R Depression subscale | IMT significantly reduced depressive symptoms (p < 0.001); effects generally stronger than NIMT across outcomes (permissive thoughts), though not all differences reached significance. |

| Landry (2014) [8] USA | 51 healthy adults | crossover design (n = 51): HSB, Silence. Age: 50.5 ± 10.0 | 12 min session with bowl near the ear + 20 min directed relaxation | Silence group sat quietly for 12 min, then did 20 min of guided relaxation. | SBP, DBP, HR, PANAS | HSB significantly reduced SBP (p = 0.044) and HR (p = 0.003) compared to Silence; PANAS scores decreased significantly in both conditions (p < 0.001), with no between-condition differences. |

| Wepner et al. (2008) [27] Austria | 54 adults with chronic back pain | TSB (n = 18), Placebo (n = 18), Control (n = 18). Age: 47.06 ± 9.33 | Six sessions over 4 weeks using one selected bowl placed on painful areas and struck | Placebo group had the bowl placed on the body without sound or vibration. Control group had no intervention and continued usual care. | VAS, RMDQ, SF-36, MDBF, HR, Skin Conductance, HRV | Pain intensity and heart rate significantly decreased (p < 0.05); no significant effect on function (RMDQ), quality of life (SF-36), and skin conductance. Mood improved only short term (MDBF). |

| Authors (Year) Country | Participants | Sample Size and Age: M ± SD | Intervention | Comparison | Outcome Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hasani et al. (2025) [10] Iran | 60 adult patients awaiting coronary angiography in a hospital setting | TSB (n = 30), age: 54.63 ± 9.14. UC (n = 30), age: 57.13 ± 10.50. | Received a 10 min sound therapy using a 10 cm bowl on the palm, struck four times for 15 s each. | UC group received only routine care without sound therapy. | State Anxiety Inventory, BP, HR, RR | TSB reduced anxiety (p < 0.001); no significant effect on BP, HR, and RR. |

| Pozmogova et al. (2023) [28] Netherlands | 20 adults with PTSD (Ukrainian refugees) | TSB (n = 10), age range:40–55. Control (n = 10), age range: 40–55. | Received Tibetan bowl massage with color visualization and breathing, 15–20 min per session, twice weekly for 6 weeks. | Control group received stress management only with no sound or visual input. | Short Form 36-Item Health Survey (vitality, mental health, social functioning, and emotional role functioning) | Psychological well-being improved (p < 0.05); control group showed no significant changes. |

| Oguy et al. (2021) [29] Russian Federation | 81 healthy adults | Stage 1: only single-group (n = 19), age: 30.36 ± 13.94 Stage 2: Intervention (n = 31), age: 38.65 ± 9.28 Control (n = 31), age: 35.55 ± 4.75 | Received 50 min vibroacoustic massage with a 25 cm bowl placed on the body, struck nine times per spot (1/s). | Control group received acoustic exposure only, about 2 m away with no physical contact. | Stage 1: Well-being, Activity, Mood scale, Zung, SKAS, Stage 2: HRV, hemodynamics | Well-being, depressive symptoms, and anxiety improved (p < 0.01); mood nonsignificant (p = 0.244). |

| Trivedi & Saboo (2019) [30] India | 33 adults with sleep or stress-related concerns | HSB (n = 16), mean age: 28 SS (n = 17), mean age: 25 | HSB group received a 20 min session with singing bowls and Tingsha | SS group rested in a supine position for 20 min without sound stimulation | Stress Index, HR, RMSSD | Stress Index and HR decreased, RMSSD increased (p < 0.05); control group showed no significant changes. |

| Authors (Year) Country | Participants | Sample Size and Age: M ± SD | Intervention | Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim & Choi (2023) [20] Republic of Korea | General adults | n = 17, age: 25.2 ± 3.5 | 5 min non-contact bowl striking (260 mm × 115 mm bowl, struck six times at 50 sec intervals) | EEG (Delta, Theta, Alpha, Beta, Gamma) | Delta and theta waves increased (135.2% and 117.1%), and 6.68 Hz beat rose by 251.98%. Alpha, beta, and gamma waves decreased (14.7%, 6.3%, and 18.1%). Effects remained after the sound stopped. |

| Walter & Hinterberger (2022) [18] Germany | General adults | n = 34, age: 36.0 ± 13.4 | 20 min on-body singing bowl massage following the Peter Hess® method | EEG, HRV, HR, RR, TAS, CSP-14 | EEG global power decreased (p < 0.001), especially in Beta 2 (p = 0.002) and Gamma (p = 0.004); HR significantly decreased (p < 0.001); subjective well-being improved per CSP-14; HRV changes were not significant (e.g., RMSSD p = 0.057) |

| Oguy et al. (2018) [31] Russia | Adults with stress-related symptoms | n = 33, age: 35.0 ± 6.3 | 2–4 vibroacoustic massage sessions (30–70 min) using “giving” and “receiving” bowl striking techniques | ECG, HR, HRV, ZSAS, STAI | Anxiety significantly decreased after the intervention, with ZSAS dropping from 48.2 to 35.6 and STAI-SA from 39.8 to 26.3 (p < 0.05); however, symptoms partially returned after 24 h with no significant difference (p > 0.05). |

| Goldsby et al. (2017) [9] USA | General adults | n = 62, age: 49.7 ± 13.0 | 60 min sound meditation using ~95% Jambati bowls and other instruments; participants lay down surrounded by bowls. | POMS-SF, HADS, FACIT-SP, pain rating | Significant reductions in tension, anger, confusion, fatigue, anxiety, and depressive symptoms (p < 0.001); increased spiritual well-being (p < 0.01) |

| Bidin et al. (2016) [19] Italy | Adult patients with cancer | n = 12, (age not reported) | Six 60 min Bagno Armonico sessions over 3 months with on-body application of bowls, gongs, bells, and chimes; nonverbal; assessed for subjective and physiological outcomes | SF-36, PDI, HADS, DT, SCL, HRV, FACIT-F, EEG | TSB reduced distress (p = 0.0005), tonic and phasic SCL (p = 0.0091 and 0.0064), resting heart rate (p = 0.0001); increased HRV and oxygenation (p = 0.0041 and 0.0003). EEG showed decreased alpha and beta (p = 0.046 and 0.090), increased coherence (p = 0.084). Others not significant. |

| Outcome | No. of Studies | Risk of Bias | Certainty of Assessment a Inconsistency Indirectness Imprecision | No. of Participants a | Effect Size b | Certainty | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 1 RCT 1 QES 4 single-group | Low | No serious | Not serious | No serious | 110 | 1.51 and 2.18 | Moderate |

| Depressive symptoms | 2 RCT 1 QES 2 single-group | Moderate | Moderate | No serious | No serious | 97 | Between 0.5 and 1.8 | Low to Moderate |

| Well-Being | 1 QES 1 single-group | Moderate | NA | No serious | Serious | 20 | 2.1 | Low |

| Quality of Life | 1 RCT 1 QES 1 single-group | Moderate | Serious | Low | Serious | 74 | 0.09 and 3.93 | Low |

| Heart Rate Variability: RMSSD | 2 RCT 2 QES 2 single-group | Moderate | No serious | Low | Moderate | 181 | Between 0.6 and 0.8 | Low to Moderate |

| Heart Rate | 2 RCT 2 QES 2 single-group | Moderate | No serious | Low | Moderate | 182 | Between −0.5 and 0.8 | Low |

| Brainwave Activity | 1 RCT 3 single-group | Low | No serious | No serious | No serious | 50 | 1.3 | Low to Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, F.-W.; Yang, Y.-H.; Wang, J.-Y. Effects of Tibetan Singing Bowl Intervention on Psychological and Physiological Health in Adults: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2002. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162002

Lin F-W, Yang Y-H, Wang J-Y. Effects of Tibetan Singing Bowl Intervention on Psychological and Physiological Health in Adults: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(16):2002. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162002

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Fei-Wen, Ya-Hui Yang, and Jiun-Yi Wang. 2025. "Effects of Tibetan Singing Bowl Intervention on Psychological and Physiological Health in Adults: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 13, no. 16: 2002. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162002

APA StyleLin, F.-W., Yang, Y.-H., & Wang, J.-Y. (2025). Effects of Tibetan Singing Bowl Intervention on Psychological and Physiological Health in Adults: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 13(16), 2002. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162002