Effects of an App-Based Intervention to Improve Awareness and Usage of Early Childhood Intervention Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Randomized Controlled Trial of the CoronabaBY Study from Germany

Abstract

1. Introduction

Study Aim

- Parents who accessed the app module (intervention group, IG) would have a significantly higher awareness of ECI at post-test compared to parents who did not access the app module (waitlist control group, WCG).

- Parents in the IG would have a significantly higher usage rate of ECI at post-test compared to parents of the WCG.

- These effects in awareness and usage of ECI between IG and WCG would also show in the follow-up.

- The more stressed the parents were, the higher the awareness of ECI was—both for the pre-test, the post-test and the follow-up.

- The more stressed the parents were, the higher the usage rate of ECI was—both for the pre-test, the post-test and the follow-up.

- Highly stressed parents who accessed the app module (intervention group, IG) would have a significantly higher awareness of ECI at post-test and follow-up compared to highly stressed parents who did not access the app module (waitlist control group, WCG).

- Highly stressed parents of the IG would have a significantly higher usage rate of ECI at post-test and follow-up compared to highly stressed parents of the WCG.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

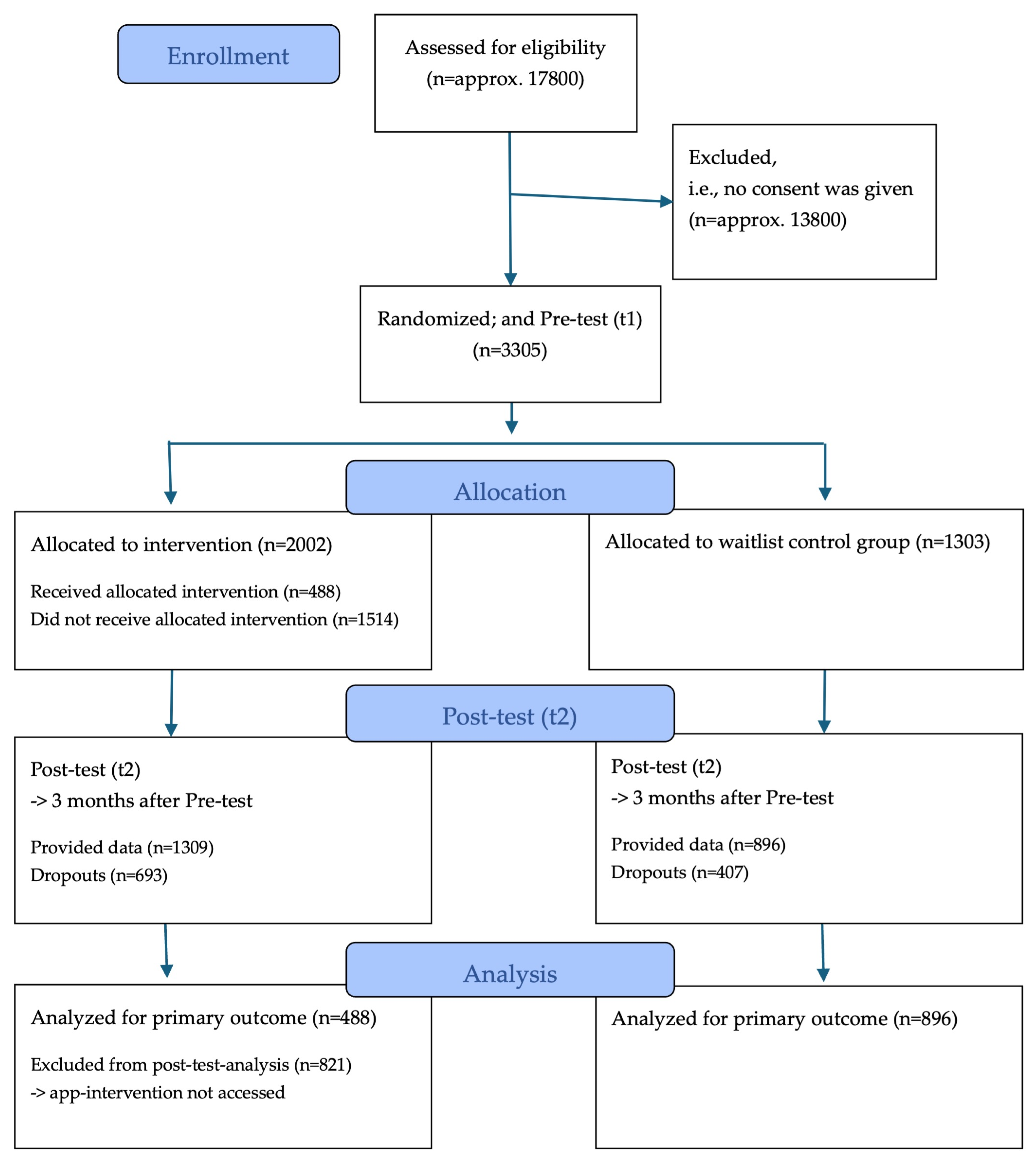

2.2. Recruitment and Procedure

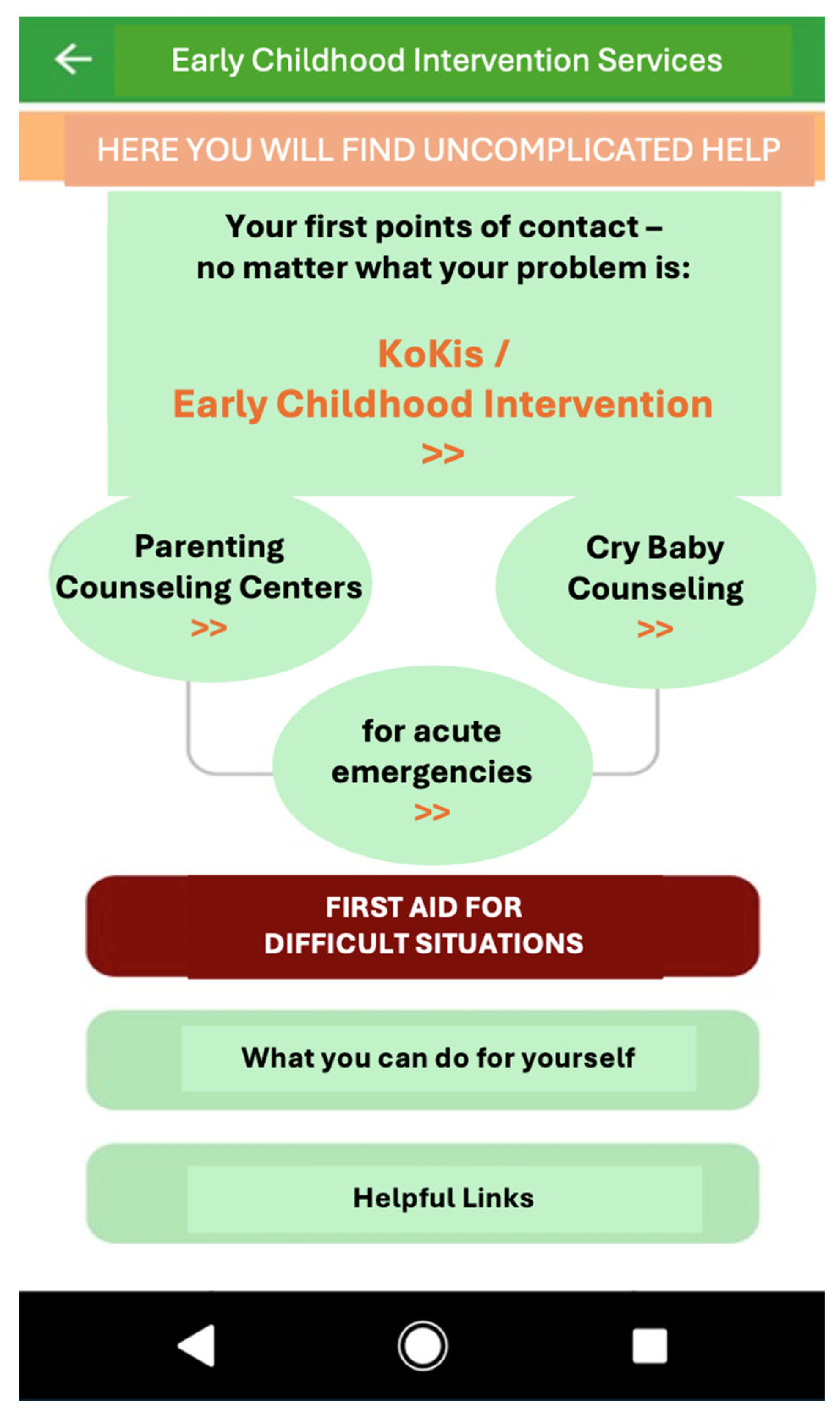

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Usage and Evaluation of the App-Based Intervention

2.4.2. Awareness and Usage of Early Childhood Intervention

2.4.3. Parenting Stress

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.5.1. Power

2.5.2. Analysis Plan

3. Results

3.1. Participant Enrollment and Sample Characteristics

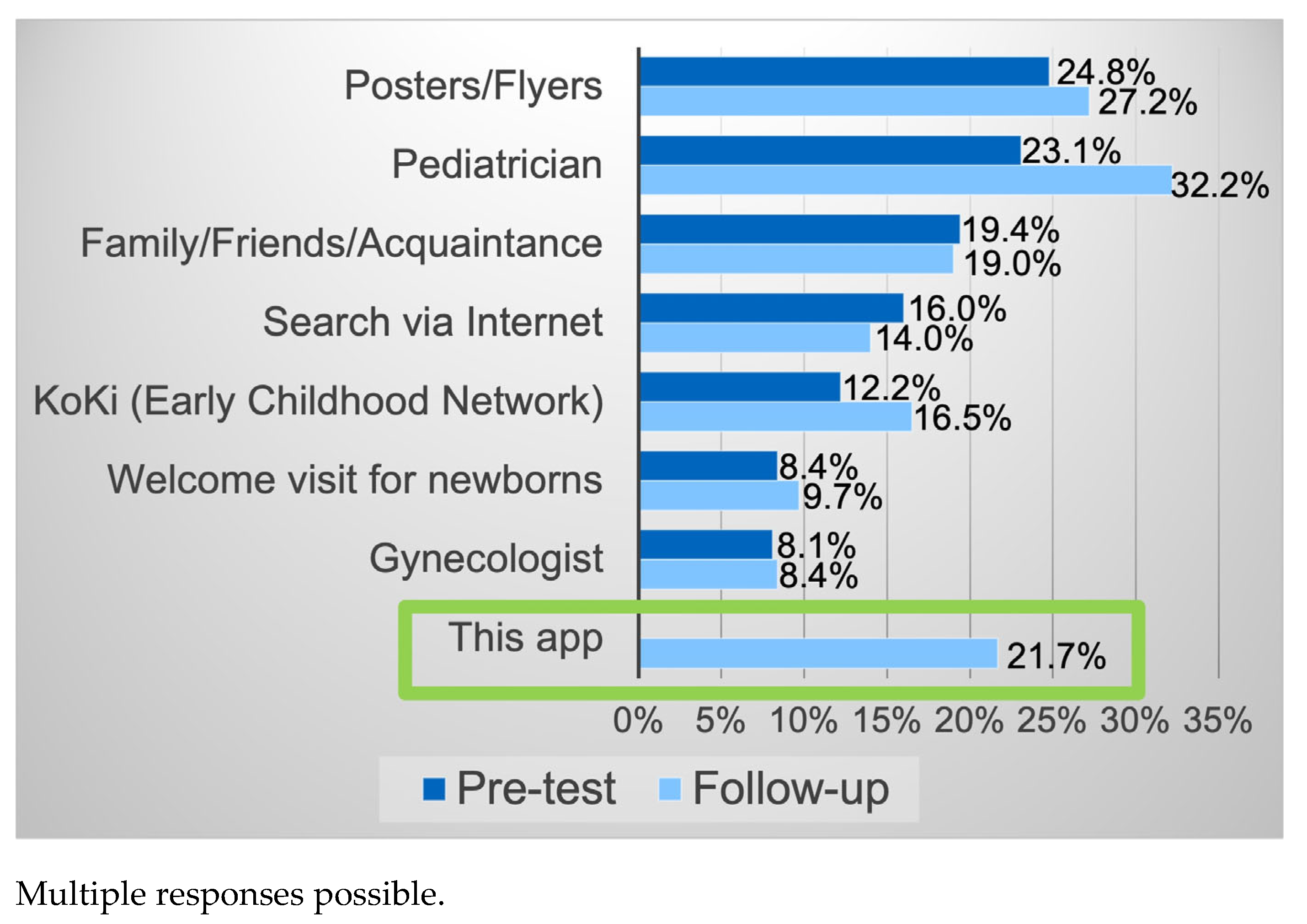

3.2. App-Based Intervention—Usage and Evaluation

3.3. Awareness and Usage of Early Childhood Intervention Services According to Study Group

3.3.1. Awareness According to Study Group

3.3.2. Usage According to Study Group

3.4. Awareness and Usage of Early Childhood Intervention Services According to Parenting Stress Levels

3.4.1. Awareness According to Parenting Stress Levels

3.4.2. Usage According to Parenting Stress Levels

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ECI | Early Childhood Intervention |

| IG | Intervention group |

| WCG | Waitlist control group |

| PSI | Parenting stress index |

| EBI | Eltern-Belastungs-Inventar |

| ITT | Intention-to-treat |

References

- Heilig, L. Risikokonstellationen in der frühen Kindheit: Auswirkungen biologischer und psychologischer Vulnerabilitäten sowie psychosozialer Stressoren auf kindliche Entwicklungsverläufe. Z. Erzieh. 2014, 17, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, S.; Ulrich, S.M.; Sann, A.; Liel, C. Self-Reported Psychosocial Stress in Parents With Small Children. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2020, 117, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, P.K.; Gupta, J.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Kumar, R.; Meena, A.K.; Madaan, P.; Sharawat, I.K.; Gulati, S. Psychological and Behavioral Impact of Lockdown and Quarantine Measures for COVID-19 Pandemic on Children, Adolescents and Caregivers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2021, 67, fmaa122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nationales Zentrum Frühe Hilfen (NZFH) (Hrsg.). Monitoring Frühe Hilfen. Wissenschaftlicher Bericht 2023 zur Bundesstiftung Frühe Hilfen; Nationales Zentrum Frühe Hilfen (NZFH) (Hrsg.): Cologne, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mariotti, A. The effects of chronic stress on health: New insights into the molecular mechanisms of brain-body communication. Future Sci. OA 2015, 1, FSO23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, M.-F.; Lord, C.; Andrews, J.; Juster, R.-P.; Sindi, S.; Arsenault-Lapierre, G.; Fiocco, A.J.; Lupien, S.J. Chronic stress, cognitive functioning and mental health. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2011, 96, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, Y.; Furuyashiki, T. The impact of stress on immune systems and its relevance to mental illness. Neurosci. Res. 2022, 175, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tröster, H. Eltern-Belastungs-Inventar (EBI): Deutsche Version des Parenting Stress Index (PSI) von R.R. Abidin; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ostberg, M.; Hagekull, B. A structural modeling approach to the understanding of parenting stress. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 2000, 29, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, R. The Determinants of Parenting Behavior. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1992, 21, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, G.J.; Yeung, W.J.; Brooks-Gunn, J.; Smith, J.R. How Much Does Childhood Poverty Affect the Life Chances of Children? Am. Sociol. Rev. 1998, 63, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weierstall-Pust, R.; Schnell, T.; Heßmann, P.; Feld, M.; Höfer, M.; Plate, A.; Müller, M.J. Stressors related to the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, and the Ukraine crisis, and their impact on stress symptoms in Germany: Analysis of cross-sectional survey data. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüken-Klaßen, D.; Neumann, R.; Elsas, S. kontakt.los! Bildung und Beratung für Familien während der Corona-Pandemie; ifb-MATERIALIEN 2-2020; Staatsinstitut für Familienforschung an der Universität Bamberg: Bamberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Huebener, M.; Waights, S.; Spiess, C.K.; Siegel, N.A.; Wagner, G.G. Parental well-being in times of COVID-19 in Germany. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2021, 19, 91–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armbruster, S.; Klotzbücher, V. Lost in Lockdown? COVID-19, Social Distancing, and Mental Health in Germany: Discussion Paper No. 2020-04; Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg: Freiburg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Buechel, C.; Friedmann, A.; Eber, S.; Behrends, U.; Mall, V.; Nehring, I. The change of psychosocial stress factors in families with infants and toddlers during the COVID-19 pandemic. A longitudinal perspective on the CoronabaBY study from Germany. Front. Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1354089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedmann, A.; Buechel, C.; Seifert, C.; Eber, S.; Mall, V.; Nehring, I. Easing pandemic-related restrictions, easing psychosocial stress factors in families with infants and toddlers? Cross-sectional results of the three wave CoronabaBY study from Germany. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2023, 17, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannotti, M.; Mazzoni, N.; Bentenuto, A.; Venuti, P.; de Falco, S. Family adjustment to COVID-19 lockdown in Italy: Parental stress, coparenting, and child externalizing behavior. Fam. Process 2021, 61, 745–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, E.L.; Smith, D.; Caccavale, L.J.; Bean, M.K. Parents Are Stressed! Patterns of Parent Stress Across COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 626456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubman-Ben-Ari, O.; Ben-Yaakov, O.; Chasson, M. Parenting stress among new parents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 117, 105080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, N.; Hetherington, E.; McArthur, B.A.; McDonald, S.; Edwards, S.; Tough, S.; Madigan, S. Maternal depressive and anxiety symptoms before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: A longitudinal analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westrupp, E.M.; Bennett, C.; Berkowitz, T.; Youssef, G.J.; Toumbourou, J.W.; Tucker, R.; Andrews, F.J.; Evans, S.; Teague, S.J.; Karantzas, G.C.; et al. Child, parent, and family mental health and functioning in Australia during COVID-19: Comparison to pre-pandemic data. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 32, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, B.S.; Hutchison, M.; Tambling, R.; Tomkunas, A.J.; Horton, A.L. Initial Challenges of Caregiving During COVID-19: Caregiver Burden, Mental Health, and the Parent-Child Relationship. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2020, 51, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, G.; Lanier, P.; Wong, P.Y.J. Mediating Effects of Parental Stress on Harsh Parenting and Parent-Child Relationship during Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic in Singapore. J. Fam. Violence 2020, 37, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crnic, K.A. Parenting stress and child behavior problems: Developmental psychopathology perspectives. Dev. Psychopathol. 2024, 36, 2369–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deater-Deckard, K. Parenting stress and child adjustment: Some old hypotheses and new questions. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 1998, 5, 314–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Devine, J.; Napp, A.-K.; Kaman, A.; Saftig, L.; Gilbert, M.; Reiß, F.; Löffler, C.; Simon, A.M.; Hurrelmann, K.; et al. Three years into the pandemic: Results of the longitudinal German COPSY study on youth mental health and health-related quality of life. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1129073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlack, R.; Neuperdt, L.; Junker, S.; Eicher, S.; Hölling, H.; Thom, J.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Beyer, A.-K. Changes in mental health in the German child and adolescent population during the COVID-19 pandemic—Results of a rapid review. J. Health Monit. 2023, 8 (Suppl. 1), 2–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racine, N.; McArthur, B.A.; Cooke, J.E.; Eirich, R.; Zhu, J.; Madigan, S. Global Prevalence of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Children and Adolescents During COVID-19: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egle, U.T.; Franz, M.; Joraschky, P.; Lampe, A.; Seiffge-Krenke, I.; Cierpka, M. Gesundheitliche Langzeitfolgen psychosozialer Belastungen in der Kindheit—Ein Update. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2016, 59, 1247–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laucht, M.; Schmidt, M.H.; Esser, G. Motorische, kognitive und sozial-emotionale Entwicklung von 11-Jährigen mit frühkindlichen Risikobelastungen: Späte Folgen. Z. Kinder Jugendpsychiatrie Psychother. 2002, 30, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopatina, O.L.; Panina, Y.A.; Malinovskaya, N.A.; Salmina, A.B. Early life stress and brain plasticity: From molecular alterations to aberrant memory and behavior. Rev. Neurosci. 2021, 32, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nationales Zentrum Frühe Hilfen (NZFH). Frühe Hilfen: Ein Überblick. Available online: https://www.fruehehilfen.de/fileadmin/user_upload/fruehehilfen.de/pdf/Publikation-NZFH-Infopapier-Fruehe-Hilfen-Ein-Ueberblick-bf.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Schlack, H.G. Sozialpädiatrie: Eine Standortbestimmung. In Sozialpädiatrie—Gesundheitswissenschaft und Pädiatrischer Alltag; Schlack, H.G., von Kries, R., Thyen, U., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Franchett, E.E.; Ramos de Oliveira, C.V.; Rehmani, K.; Yousafzai, A.K. Parenting interventions to promote early child development in the first three years of life: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Familie, Arbeit und Soziales. Frühe Hilfen. Available online: https://www.stmas.bayern.de/kinderschutz/fruehe-hilfen/index.php (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Buechel, C.; Nehring, I.; Seifert, C.; Eber, S.; Behrends, U.; Mall, V.; Friedmann, A. A cross-sectional investigation of psychosocial stress factors in German families with children aged 0-3 years during the COVID-19 pandemic: Initial results of the CoronabaBY study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küster, E.-U.; Peterle, C. Kommunale Frühe Hilfen Während der Corona-Pandemie: Faktenblatt zu den NZFH-Kommunalbefragungen; Herausgegeben vom Nationalen Zentrum Frühe Hilfen (NZFH): Cologne, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann-Kötting, G.; Renner, I. Frühe Hilfen–Entwicklung und Etablierung von digitalen Maßnahmen zur Unterstützung eines analogen Arbeitsfeldes. Forum Sex. Fam. 2020, 36–41. Available online: https://www.sexualaufklaerung.de/publikation/forum-2-2020-digitale-beratung/ (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Neumann, A.; Ulrich, S.M.; Hänelt, M.; Chakraverty, D.; Lux, U.; Renner, I. Zur Erreichbarkeit Junger Familien vor und Während der Corona-Pandemie: Welche Unterstützungsangebote Werden von Wem Genutzt? Faktenblatt 4 zur Studie »Kinder in Deutschland 0-3 2022«; Herausgegeben vom Nationalen Zentrum Frühe Hilfen (NZFH): Cologne, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sahrai, D.; Bittlingmayer, U.H. Frühe Hilfen für alle? Erreichbarkeit von Eltern in den Frühen Hilfen: Expertise. Materialien zu Frühen Hilfen 18; Herausgegeben vom Nationalen Zentrum Frühe Hilfen (NZFH): Cologne, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Testzentrale. EBI. Eltern-Belastungs-Inventar. Available online: https://www.testzentrale.de/shop/eltern-belastungs-inventar.html (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Eickhorst, A.; Schreier, A.; Brand, C.; Lang, K.; Liel, C.; Renner, I.; Neumann, A.; Sann, A. Inanspruchnahme von Angeboten der Frühen Hilfen und darüber hinaus durch psychosozial belastete Eltern. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2016, 59, 1271–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, S.M.; Walper, S.; Renner, I.; Liel, C. Characteristics and patterns of health and social service use by families with babies and toddlers in Germany. Public Health 2022, 203, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, K.; Buechel, C.; Augustin, M.; Friedmann, A.; Mall, V.; Nehring, I. Psychosocial stress in families of young children after the pandemic: No time to rest. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2025, 19, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, C.M.; Bierman, K.L. Technology-assisted interventions for parents of young children: Emerging practices, current research, and future directions. Early Child. Res. Q. 2015, 33, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitenstein, S.M.; Gross, D.; Christophersen, R. Digital Delivery Methods of Parenting Training Interventions: A Systematic Review. Worldviews Ev Based Nurs. 2014, 11, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäggi, L.; Aguilar, L.; Alvarado Llatance, M.; Castellanos, A.; Fink, G.; Hinckley, K.; Huaylinos Bustamante, M.-L.; McCoy, D.C.; Verastegui, H.; Mäusezahl, D.; et al. Digital tools to improve parenting behaviour in low-income settings: A mixed-methods feasibility study. Arch. Dis. Child 2023, 108, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Statistiken zur Smartphone-Nutzung in Deutschland. Available online: https://de.statista.com/themen/6137/smartphone-nutzung-in-deutschland/#topicOverview (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Renner, I.; van Staa, J.; Neumann, A.; Sinß, F.; Paul, M. Frühe Hilfen aus der Distanz—Chancen und Herausforderungen bei der Unterstützung psychosozial belasteter Familien in der COVID-19-Pandemie. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2021, 64, 1603–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, S.; Tracy, M. Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Ann. Epidemiol. 2007, 17, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atteslander, P. Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung, 13th ed.; neu bearbeitete und erweiterte Auflage; ESV basics; Erich Schmidt Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Micheel, H.-G. Quantitative Empirische Sozialforschung; UTB Soziale Arbeit, Erziehungswissenschaften; Reinhardt: Munich, Germany, 2010; Volume 8439. [Google Scholar]

| Sociodemographics of Parents | Total Sample n (%) | Intervention Group n (%) | Waitlist Control Group n (%) | p b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | 3072 (92.9) | 1857 (92.7) | 1215 (93.2) | 0.579 |

| Mother tongue German | 3053 (92.3) | 1846 (92.2) | 1207 (92.6) | 0.619 |

| Educational level (at least high school diploma) | 1965 (59.5) | 1210 (60.4) | 755 (58) | 0.121 |

| Comfortable financial situation a (self-assessment) | 1762 (53.3) | 1099 (54.9) | 663 (50.9) | 0.006 |

| Age of parents and child | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Mage participants in years | 33.7 (5.0) | 33.7 (5.1) | 33.7 (5.0) | 0.826 |

| Mage child in months | 16.7 (12.1) | 16.4 (12.1) | 17.2 (12.1) | 0.064 |

| Parenting Stress (acc. to parenting stress index) | ||||

| No findings | 1817 (55.0) | 1104 (55.1) | 713 (54.7) | |

| Stressed | 1117 (33.8) | 670 (33.5) | 447 (34.3) | 0.856 |

| Highly stressed | 371 (11.2) | 228 (11.4) | 143 (11.0) |

| Outcome Variable | Intervention Group (IG) n (%) | Waitlist Control Group (WCG) n (%) | p | Cramer’s V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of ECI | ||||

| t1 (pre-test) | 926 (70.6) | 598 (73.2) | 0.193 | 0.028 |

| t2 (post-test) | 271 (86.9) a | 472 (85.7) | 0.625 | 0.017 |

| Follow-up | 173 (90.6) a | 273 (86.1) | 0.137 | 0.066 |

| Usage of ECI | ||||

| t1 (pre-test) | 691 (34.5) | 486 (37.3) | 0.100 | 0.029 |

| t2 (post-test) | 59 (12.1) a,b | 107 (8.2) b | 0.012 | 0.060 |

| Follow-up | 28 (9.9) a,c | 51 (9.8) c | 0.961 | 0.002 |

| Outcome Variable | Not Stressed n (%) | Stressed n (%) | Highly Stressed n (%) | p (V) (Not Stressed vs. Stressed) | p (V) (Stressed vs. Highly Stressed) | p (V) (Not Stressed vs. Highly Stressed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of ECI | ||||||

| t1 (pre-test) | 958 (76.6) | 465 (68.1) | 101 (51.5) | <0.001 (0.093) | <0.001 (0.144) | <0.001 (0.194) |

| Follow-up | 275 (89.9) | 123 (87.9) | 48 (77.4) | 0.525 (0.030) | 0.058 (0.134) | 0.006 (0.142) |

| Usage of ECI | ||||||

| t1 (pre-test) | 567 (31.2) | 434 (38.9) | 175 (47.2) | <0.001(0.078) | 0.005 (0.073) | <0.001 (0.127) |

| Follow-up | 49 (7.0) a | 46 (11.2) a | 31 (17.4) a | 0.013 (0.074) | 0.042 (0.084) | <0.001 (0.146) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buechel, C.; Mall, V.; Nehring, I.; Friedmann, A. Effects of an App-Based Intervention to Improve Awareness and Usage of Early Childhood Intervention Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Randomized Controlled Trial of the CoronabaBY Study from Germany. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2000. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162000

Buechel C, Mall V, Nehring I, Friedmann A. Effects of an App-Based Intervention to Improve Awareness and Usage of Early Childhood Intervention Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Randomized Controlled Trial of the CoronabaBY Study from Germany. Healthcare. 2025; 13(16):2000. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162000

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuechel, Catherine, Volker Mall, Ina Nehring, and Anna Friedmann. 2025. "Effects of an App-Based Intervention to Improve Awareness and Usage of Early Childhood Intervention Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Randomized Controlled Trial of the CoronabaBY Study from Germany" Healthcare 13, no. 16: 2000. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162000

APA StyleBuechel, C., Mall, V., Nehring, I., & Friedmann, A. (2025). Effects of an App-Based Intervention to Improve Awareness and Usage of Early Childhood Intervention Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Randomized Controlled Trial of the CoronabaBY Study from Germany. Healthcare, 13(16), 2000. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162000

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)