‘Finally, in Hands I Can Trust’: Perspectives on Trust in Motor Neurone Disease Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Understanding Core Constructs of Trust

3. Trust and MND—From Our Personal Perspectives

4. Engagement and Co-Production

5. Experiences Eroding Trust

6. Experiences Facilitating Trust

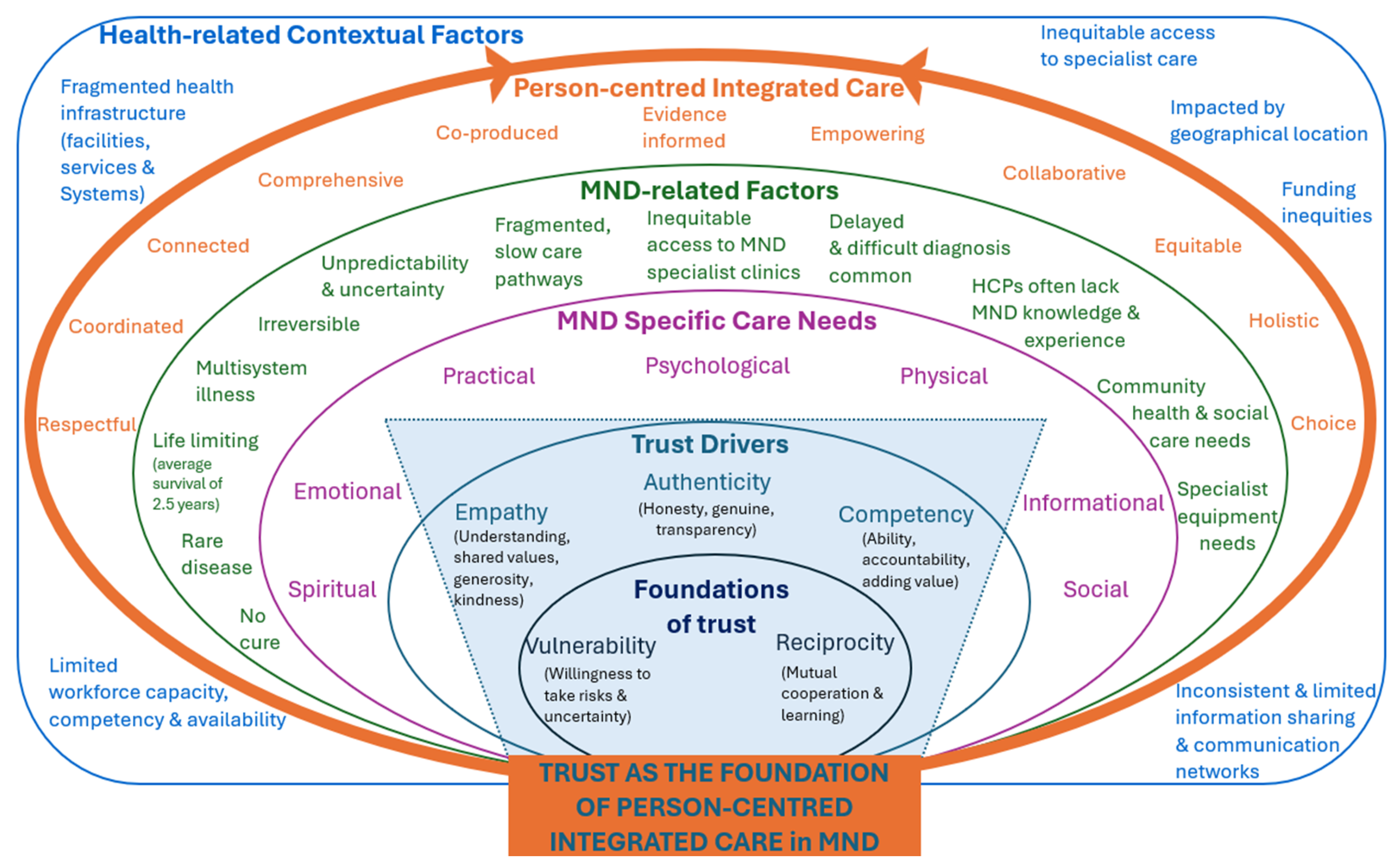

7. Trust as Foundation of Person-Centred Integrated Care in MND

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brewah, H.; Borrett, K.; Tavares, N.; Jarrett, N. Perceptions of People with Motor Neurone Disease, Families and HSCPs: A Literature Review. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2022, 27, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, K.; Fisher, G.; Schutz, A.; Carr, S.; Heard, S.; Reynolds, M.; Goodwin, N.; Hogden, A. Connecting Care Closer to Home: Evaluation of a Regional Motor Neurone Disease Multidisciplinary Clinic. Healthcare 2025, 13, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zonneveld, N.; Driessen, N.; Stüssgen, R.A.; Minkman, M.M. Values of Integrated Care: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Integr. Care 2018, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, D.A.; Jack, K.; Wibberley, C. The need to consider ‘temporality’ in person-centred care of people with motor neurone disease. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2023, 29, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, S.; Fitzpatrick, A.; Azim, F.T.; Ariza-Vega, P.; Bellwood, P.; Burns, J.; Burton, E.; Fleig, L.; Clemson, L.; Christiane, A.; et al. Defining and Implementing Patient-centered Care: An Umbrella Review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 1679–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, A.C.; Wilber, K.; Mosqueda, L. Person-Centered Care for Older Adults with Chronic Conditions and Functional Impairment: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, e1–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.A.; Nong, P.; Platt, J. Fifty Years of Trust Research in Health Care: A Synthetic Review. Milbank Q. 2023, 101, 126–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, G.; Timonen, V.; Hardiman, O. Understanding Psycho-social Processes Underpinning Engagement with Services in Motor Neurone Disease: A Qualitative Study. Palliat. Med. 2014, 28, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, M.; Madden, C.; Maguire, S.; Heverin, M.; Vajda, A.; Staines, A.; Hardiman, O. Patient Journey to a Specialist Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Multidisciplinary Clinic: An Exploratory Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.; Britten, N.; Lydahl, D.; Naldemirci, Ö.; Elam, M.; Wolf, A. Barriers and Facilitators to the Implementation of Person-centred Care in Different Healthcare Contexts. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2017, 31, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogden, A.; Paynter, C.; Hutchinson, K. How Can We Improve patient-centered Care of Motor Neuron disease? Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2020, 10, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoesmith, C.; Abrahao, A.; Benstead, T.; Chum, M.; Dupre, N.; Izenberg, A.; Johnston, W.; Kalra, S.; Leddin, D.; O’Connell, C.; et al. Canadian Best Practice Recommendations for the Management of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2020, 192, E1453–E1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Motor Neurone Disease: Assessment and Management. 2019 23/7/19. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng42 (accessed on 22 June 2023).

- Griffith, D.M.; Bergner, E.M.; Fair, A.S.; Wilkins, C.H. Using Mistrust, Distrust, and Low Trust Precisely in Medical Care and Medical Research Advances Health Equity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 60, 442–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glennie, N.; Harris, F.M.; France, E.F. Perceptions and Experiences of Control Among People Living with Motor Neurone Disease: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 45, 2554–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, K.; Maguire, S.; Corr, B.; Normand, C.; Hardiman, O.; Galvin, M. Discrete Choice Experiment for Eliciting Preference for Health Services for Patients with ALS and their Informal Caregivers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, R.; Attrill, S.; Radakovic, R.; Doeltgen, S. Exploring Clinical Management of Cognitive and Behavioural Deficits in MND. A Scoping Review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2023, 116, 107942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radakovic, R.; Copsey, H.; Moore, C.; Mioshi, E. Development of the MiNDToolkit for Management of Cognitive and Behavioral Impairment in Motor Neuron Disease. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2020, 10, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, G.; Hynes, G. Decision-making Among Patients and their Family in ALS Care: A Review. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2018, 19, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, S.; Ellajosyula, R. Capacity Issues and Decision-making in Dementia. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2016, 19 (Suppl. 1), S34–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, S.J.; Cramm, J.M.; Nieboer, A.P. The Importance of Patient-centered Care and Co-creation of Care for Satisfaction with Care and Physical and Social Well-being of Patients with Multi-morbidity in the Primary Care Setting. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calnan, M.; Rowe, R. Trust Relations in a Changing Health Service. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2008, 13 (Suppl. 3), 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.A. Trust, Health Care Relationships, and Chronic Illness: A Theoretical Coalescence. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2016, 3, 2333393616664823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, M.; Donelson, A. Trust is the Engine of Change: A Conceptual Model for Trust Building in Health Systems. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2022, 39, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rørtveit, K.; Hansen, B.S.; Leiknes, I.; Joa, I.; Testad, I.; Severinsson, E. Patients’ Experiences of Trust in the Patient-Nurse Relationship—A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Open J. Nursi. 2015, 5, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souvatzi, E.; Katsikidou, M.; Arvaniti, A.; Plakias, S.; Tsiakiri, A.; Samakouri, M. Trust in Healthcare, Medical Mistrust, and Health Outcomes in Times of Health Crisis: A Narrative Review. Societies 2024, 14, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, F.; Morriss, A. Begin with Trust. In Harvard Business Review; Harvard business review: Brighton, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Romford, J. The Frances Frei Trust Triangle-It’s Workings, Examples & More. 2024. Available online: https://agilityportal.io/blog/trust-triangle (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Moore, J.E.; Khan, S. Cultivating Trust and Navigating Power Course and Workbook; The Center for Implementation: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P.R.; Calnan, M.W. Chains of (Dis)Trust:Exploring the Underpinnings of Knowledge-sharing and Quality Care across Mental Health Services. Sociol. Health Illn. 2016, 38, 286–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhaecht, K.; Lachman, P.; Van der Auwera, C.; Seys, D.; Claessens, F.; Panella, M.; De Ridder, D. The “House of Trust”. A Framework for Quality Healthcare and Leadership. F1000Research 2024, 13, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, L.; Goodwin, N. What are the Principles that Underpin Integrated Care? Int. J. Integr. Care 2014, 14, e037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, A.; Oldham, J. Person-centred care: What Is It And How Do We get There? Future Hosp. J. 2016, 3, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, N. Understanding Integrated care. Int. J. Integr. Care 2016, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennox-Chhugani, N.; Alvarez-Rosete, A.; Aldasori, E.; Gil-Salmeron, A. Promoting Integrated Care Across the World. Available online: https://integratedcarefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/IFIC3692-Annual-Survey-2022-A4-v262367.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Sedikides, C.; Schlegel, R.J. Distilling the Concept of Authenticity. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2024, 3, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.C.; Tan, L.; Le, M.K.; Tang, B.; Liaw, S.Y.; Tierney, T.; Ho, Y.Y.; Lim, B.E.E.; Lim, D.; Ng, R.; et al. The Development of Empathy in the Healthcare Setting: A Qualitative Approach. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hake, A.B.; Post, S.G. Kindness: Definitions and a Pilot Study for the Development of a Kindness Scale in Healthcare. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, A.; González-Ortiz, L.G.; Gabutti, L.; Lumera, D. What’s the role of kindness in the healthcare context? A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malenfant, S.; Jaggi, P.; Hayden, K.A.; Sinclair, S. Compassion in Healthcare: An Updated Scoping Review of the Literature. BMC Palliat. Care 2022, 21, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwame, A.; Petrucka, P.M. A literature-based Study of Patient-centered Care and Communication in Nurse-patient Interactions: Barriers, Facilitators, and the Way Forward. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, R.M.; Pii, K.H.; Eplov, L.F.; Meijer, M.; Bültmann, U.; Christensen, U. Developing Interpersonal Trust Between Service Users and Professionals in Integrated Services: Compensating for Latent Distrust, Vulnerabilities and Uncertainty Shaped by Organisational Context. Int. J. Integr. Care 2021, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strnadová, I.; Dowse, L.; Watfern, C. Doing Research Inclusively: Guidelines for Co-Producing Research with People with Disability. 2020 Sydney. Available online: https://www.disabilityinnovation.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/documents/DIIU%20Doing%20Research%20Inclusively-Guidelines%20%2817%20pages%29.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Noy, C. Sampling knowledge: The Hermeneutics of Snowball Sampling in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2008, 11, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Kim, J.A. Supportive Care Needs of Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis/Motor Neuron Disease and their Caregivers: A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 4129–4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, P.R.; Rokkas, P.; Cenko, C.; Pulvirenti, M.; Dean, N.; Carney, S.; Brown, P.; Calnan, M.; Meyer, S. A Qualitative Study of Patient (Dis)Trust in Public and Private Hospitals: The Importance of Choice and Pragmatic Acceptance for Trust Considerations in South Australia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calnan, M.; Rowe, R. Trust and Health Care. Sociol. Compass 2007, 1, 283–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Important Terms | Definitions (Adapted by Authors) |

|---|---|

| Person-centred care | Focuses on understanding and responding to everyone’s unique needs, values, circumstances, and preferences. It emphasises shared decision-making, respect for individuality, holistic care, and open communication—ensuring that care is tailored to what matters most to the person receiving it [5,34]. |

| Integrated care | Refers to coordinated strategies that aim to improve health outcomes by addressing fragmentation and fostering continuity across the care continuum—built on relationships of trust among providers, systems, and the people they serve [35,36]. |

| Trust | A relational belief in the competence, integrity, and goodwill of another [7,8]. |

| Authenticity | The quality of being genuine and aligned with one’s core values, demonstrated through consistency, sincerity, and respectful boundaries [28,37]. |

| Competency | The capacity to apply knowledge, skills, and sound judgement to effectively fulfil a role or task [26,28]. |

| Empathy | The capacity to emotionally understand and connect with another person’s experience—by sensing what they feel, seeing from their perspective, and responding with genuine care [28,38]. |

| Kindness | Is an action that supports or uplifts another, as experienced and valued by the person receiving it [39,40]. Often described as doing good without expectations. |

| Compassion | Is the emotional capacity to recognise another’s suffering through relational understanding, accompanied by a genuine motivation to alleviate that suffering through meaningful action [41]. |

| Vulnerability | Is the willingness to be emotionally open or uncertain, grounded in the belief that the other person will respond with care, respect, and dignity [42,43]. |

| Reciprocity | Reciprocity is the mutual exchange of support, effort, or understanding that fosters cooperation and shared benefit between individuals or groups [25]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lisiecka, D.; Dyson, N.; Malpress, K.; Smith, A.; McNeice, E.; Shack, P.; Hutchinson, K. ‘Finally, in Hands I Can Trust’: Perspectives on Trust in Motor Neurone Disease Care. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1994. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161994

Lisiecka D, Dyson N, Malpress K, Smith A, McNeice E, Shack P, Hutchinson K. ‘Finally, in Hands I Can Trust’: Perspectives on Trust in Motor Neurone Disease Care. Healthcare. 2025; 13(16):1994. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161994

Chicago/Turabian StyleLisiecka, Dominika, Neil Dyson, Keith Malpress, Anthea Smith, Ellen McNeice, Peter Shack, and Karen Hutchinson. 2025. "‘Finally, in Hands I Can Trust’: Perspectives on Trust in Motor Neurone Disease Care" Healthcare 13, no. 16: 1994. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161994

APA StyleLisiecka, D., Dyson, N., Malpress, K., Smith, A., McNeice, E., Shack, P., & Hutchinson, K. (2025). ‘Finally, in Hands I Can Trust’: Perspectives on Trust in Motor Neurone Disease Care. Healthcare, 13(16), 1994. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161994