Stakeholders’ Perceptions of the Nature-Based Healing Industry in South Korea: A Q Methodology Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Q Methodology Research Procedure

2.1.1. Q Concourse Organisation

2.1.2. Q Sample Selection

2.1.3. P Sample Organisation

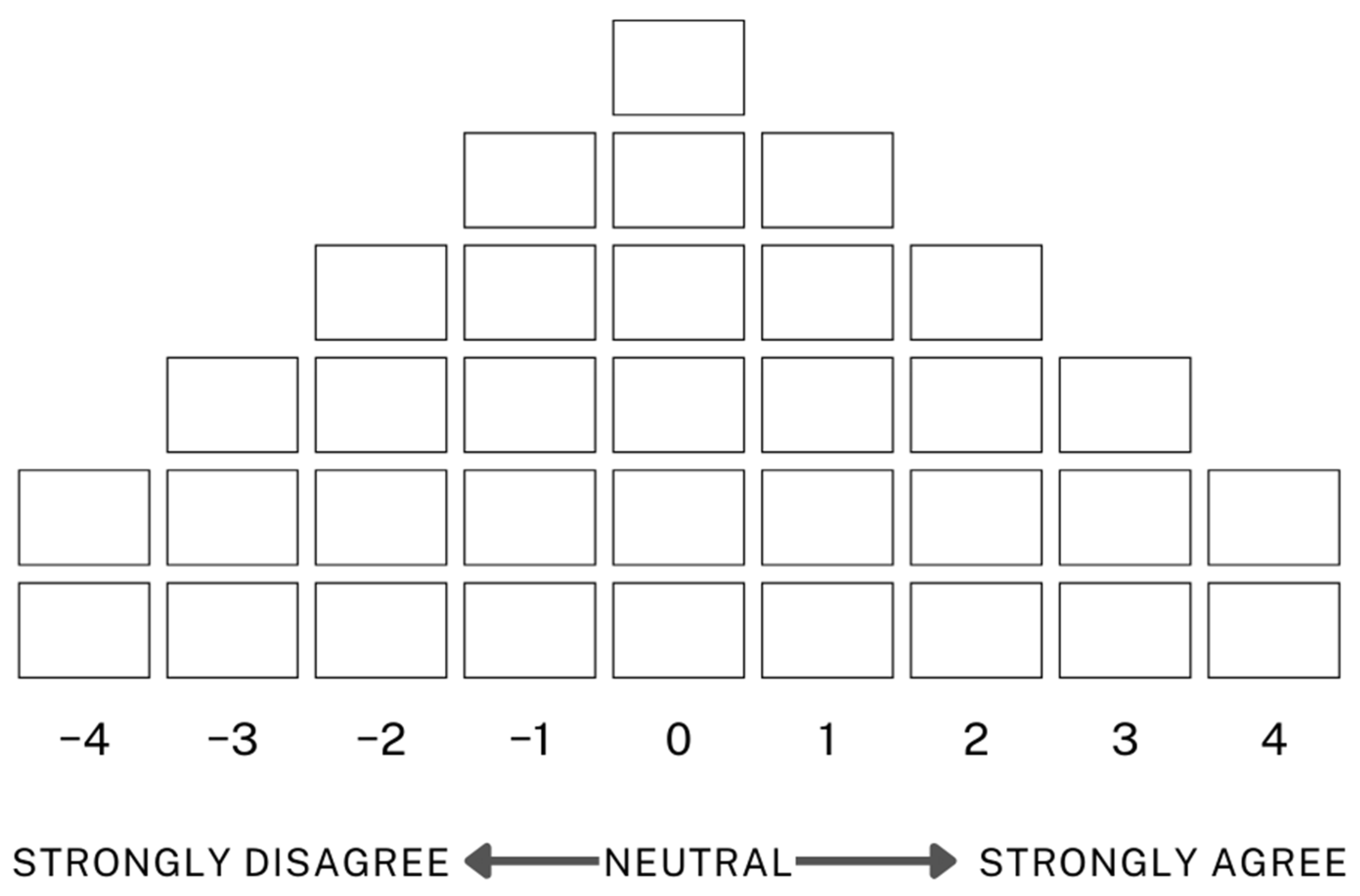

2.1.4. Q Sorting

2.1.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Analysis Results

3.2. Perception Type Characteristics

- Type 1: A comprehensive and service-oriented type emphasising universal access and public benefit

- Type 2: A professionalism-oriented type advocating for systematic administration and regional development

- Type 3: A differentiation-oriented type questioning conceptual clarity and distinctiveness

- Type 4: A sustainability-oriented type highlighting long-term effects and collaborative structures

3.2.1. Type 1: A Comprehensive and Service-Oriented Type Emphasising Universal Access and Public Benefit

- Healing services should be available to the entire population (Q8, Z = 1.672)

- The healing industry should address physical and mental recovery in a balanced way (Q1, Z = 1.589)

- Scientifically and medically proving the effectiveness of the healing industry can help with its promotion (Q14, Z = 1.492)

- Cross-sectoral cooperation between policy, health, psychology, and medical fields is necessary to advance the healing industry (Q17, Z = 1.439)

- The healing industry must encompass social, cultural, and educational aspects of health (Q2, Z = 1.313).

- The healing industry should exclude individuals with medical conditions requiring treatment (Q9, Z = −1.780)

- The intended users of the healing industry remain unclear (Q11, Z = −1.619)

- Healing programmes often feel indistinguishable from general wellness tourism (Q16, Z = −1.516)

- In some cases, the development of healing infrastructure and commercial interests ends up damaging nature (Q34, Z = −1.474)

- Researchers have not clearly defined how they are measuring the outcomes of the healing industry (Q38, Z = −1.313).

- Healing services should be available to the entire population (Q8, Z = 1.672)

- The healing industry should address physical and mental recovery in a balanced way (Q1, Z = 1.589)

- The healing industry must encompass social, cultural, and educational aspects of health (Q2, Z = 1.313).

- Researchers have not clearly defined how they are measuring the outcomes of the healing industry (Q38, Z = −1.313).

3.2.2. Type 2: A Professionalism-Oriented Type Advocating for Systematic Administration and Regional Development

- The healing industry needs a government body dedicated to its oversight (Q18, Z = 1.893)

- The healing industry needs clear and systematic guidelines for its operation and management (Q22, Z = 1.798)

- The healing industry can serve as a future-oriented strategy to address rural depopulation (Q19, Z = 1.795)

- Collaboration with experts in the planning and operation phases is essential for administrative practitioners (Q24, Z = 1.298)

- The healing industry should pursue long-term effects through repeated and continuous experiences rather than one-time programmes (Q33, Z = 1.292)

- A business structure that ensures income for residents is crucial for the sustainability of the healing industry (Q20, Z = 1.190).

- Formal facility standards overly constrain the healing industry (Q26, Z = −1.552)

- Healing programmes are more effective for physical health than for mental health (Q4, Z = −1.411)

- The healing industry should exclude individuals with medical conditions requiring treatment (Q9, Z = −1.399)

- In some cases, the development of healing infrastructure and commercial interests ends up damaging nature (Q34, Z = −1.381).

- The healing industry needs a government body dedicated to its oversight (Q18, Z = 1.893)

- The healing industry can serve as a future-oriented strategy to address rural depopulation (Q19, Z = 1.795).

3.2.3. Type 3: A Differentiation-Oriented Type Questioning Conceptual Clarity and Distinctiveness

- Healing programmes often feel indistinguishable from general wellness tourism (Q16, Z = 1.700)

- Indoor healing programmes often lack differentiation from those offered in urban settings (Q37, Z = 1.207)

- The healing industry needs clear and systematic guidelines for its operation and management (Q22, Z = 1.277)

- The effects of healing programmes often fade quickly after the experience ends (Q36, Z = 1.700)

- Due to a lack of public promotion, general awareness of healing programmes remains low (Q23, Z = 1.193).

- Korea’s healing industry has developed to the point of attracting global attention (Q29, Z = −2.225)

- Although healing programmes can be expensive, they are worth the cost (Q30, Z = −1.999)

- The perception of the healing industry is as a form of welfare that supports vulnerable or marginalized groups (Q10, Z = −1.243)

- The healing industry contributes to raising environmental awareness (Q35, Z = −1.751)

- The healing industry helps form social bonds by providing opportunities for interaction (Q7, Z = −1.396).

- Healing programmes often feel indistinguishable from general wellness tourism (Q16, Z = 1.700)

- Indoor healing programmes often lack differentiation from those offered in urban settings (Q37, Z = 1.207)

- The effects of healing programmes often fade quickly after the experience ends (Q36, Z = 1.700).

- Although healing programmes can be expensive, they are worth the cost (Q30, Z = −1.999), and

- The healing industry helps form social bonds by providing opportunities for interaction (Q7, Z = −1.396).

3.2.4. Type 4: A Sustainability-Oriented Type Highlighting Long-Term Effects and Collaborative Structures

- The healing industry should pursue long-term effects through repeated and continuous experiences rather than one-time programmes (Q33, Z = 1.678)

- Collaboration with experts in the planning and operation phases is essential for administrative practitioners (Q24, Z = 1.598)

- Although healing programmes can be expensive, they are worth the cost (Q30, Z = 1.492)

- The healing industry requires a redefinition of concepts and terminology, with clear boundaries (Q15, Z = 1.393).

- The healing industry should exclude individuals with medical conditions requiring treatment (Q9, Z = −2.273)

- Healing programmes often feel indistinguishable from general wellness tourism (Q16, Z = −1.777)

- The effects of healing programmes often fade quickly after the experience ends (Q36, Z = −1.507)

- Indoor healing programmes often lack differentiation from those offered in urban settings” (Q37, Z = −1.337).

- Although healing programmes can be expensive, they are worth the cost (Q30, Z = 1.492).

- To qualify as part of the healing industry, it must use natural environmental elements (Q12, Z = −1.245).

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Urban Green Spaces and Health; [No. WHO/EURO: 2016-3352-43111-60341]; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.-S.; Kim, J.-W.; Kim, D.-Y. The influence of healing tourism selection attributes on visitor satisfaction and behavioral intention and the moderating effect of perceived value: Focusing on visitors to National Daegwallyeong healing forest. J. Hosp. Tour. Stud. 2024, 26, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-H. A study on the success of marine healing therapy tourism: Focused on the Wando case. Cult. Interact. Stud. Seapt. Cities 2023, 29, 63–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Lee, C.-K. A study on the establishment of a conceptual model of Korean-style healing tourism and analysis of healing effects: Focusing on participants in nature-based outdoor recreation. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 31, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y. Realizing an era of regional tourism where visitors stay more frequently and longer. Korea Tour. Policy 2022, 90, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.Y. Current status and institutional foundation of wellness tourism policy. Korea Tour. Policy 2022, 89, 66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Government Legislation. Act on Research, Development and Promotion of Healing Agriculture, Act No. 17100, National Law Information Center. 2020. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/lsInfoP.do?lsiSeq=215905 (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Moon, S.-H.; Lee, S.-D.; Lee, D.-H. A study on changes in the semantic network of agro-healing through big data analysis: Focused on before and after the enactment of the Agro-Healing Act. J. Korea Acad.-Ind. Coop. Soc. 2022, 23, 780–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Kim, Y.C.; Yi, J.S.; Shin, S.J.; Yu, M.H. The Concept and Application of the Healing Industry; The Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs: Seojong, Republic of Korea, 2025; Publication Registration Number: 11-1543000-100091-01.

- Buchanan, J.M.; Tullock, G. The expanding public sector: Wagner squared. Public Choice 1977, 31, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niskanen, W.A. The peculiar economics of bureaucracy. Am. Econ. Rev. 1968, 58, 293–305. [Google Scholar]

- Tullock, G. Entry barriers in politics. Am. Econ. Rev. 1965, 55, 458–466. [Google Scholar]

- Viscusi, W.K.; Gayer, T. Behavioral public choice: The behavioral paradox of government policy. Harv. J. Law Public Policy 2015, 38, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, J.M. The constitution of economic policy. Science 1987, 236, 1433–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virani, A.; van der Wal, Z. Enhancing the effectiveness of public sector performance regimes: A proposed causal model for aligning governance design with performance logics. Perspect. Public Manag. Gov. 2023, 6, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, K.; Alsuhaibani, S.A.; Alsukait, R.F.; Alshehri, R.; Herbst, C.H.; Alhajji, M.; Lin, T.K. Behavioural economic interventions to reduce health care appointment non-attendance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palagashvili, L.; Goodman, N.P. Behavioural public policy. In Special Issue 4: A Symposium on the Behavioural Limits of the State; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; Volume 7, pp. 972–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthet, V. The impact of cognitive biases on professionals’ decision-making: A review of four occupational areas. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 802439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunstein, C.R. How Change Happens; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Al Meslamani, A.Z. Challenges in health economics research: Insights from real-world examples. J. Med. Econ. 2024, 27, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeree, R.; Diaby, V. Introduction to health economics and decision-making: Is economics relevant for the frontline clinician? Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2013, 27, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sittimart, M.; Rattanavipapong, W.; Mirelman, A.J.; Hung, T.M.; Dabak, S.; Downey, L.E.; Jit, M.; Teerawattananon, Y.; Turner, H.C. An overview of the perspectives used in health economic evaluations. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 2024, 22, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Xue, J.; Lin, K.L.; Yang, H.; Zhu, Z. Impact of supply chain disruptions on economic growth: Insights from a major public health crisis. INQUIRY J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2024, 61, 00469580241266402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncarolo, F.; Boivin, A.; Denis, J.L.; Hébert, R.; Lehoux, P. What do we know about the needs and challenges of health systems? A scoping review of the international literature. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, B.; Ju, J.H.; Kim, B.; Lee, J.Y. Stakeholders’ perceptions regarding digital therapeutics reimbursement in South Korea: Qualitative study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2023, 11, e47407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Son, Y. Stakeholder subjectivity toward ecotourism development using Q methodology: The case of Maha ecotourism site in Pyeongchang, Korea. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 931–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H. Using Q methodology to analyze stakeholders’ interests in the establishment of ecotourism facilities: The case of Seocheon, Korea. J. Ecotour. 2021, 20, 282–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.B.; Lê, S.; Kim, H.R.; Yoo, S.M.; Kang, M.S.; Chu, H.N.; Hwang, I.S.; Hong, J.H. Consumer-driven characterization of healing foods using Q methodology and Q-based sorting. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 117, 105181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.R. A primer on Q methodology. Operant Subj. 1993, 16, 91–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, W. Conspiring: A general theory for subjective communicability. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 1980, 4, 7–36. [Google Scholar]

- McKeown, B.; Thomas, D.B. Q Methodology, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rost, F. Q-sort methodology: Bridging the divide between qualitative and quantitative. An introduction to an innovative method for psychotherapy research. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2021, 21, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieteren, C.M.; Patty, N.J.; Reckers-Droog, V.T.; van Exel, J. Methodological choices in applications of Q methodology: A systematic literature review. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2023, 7, 100404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.J.; Whicker, M.L. (Eds.) Handbook of Research Methods in Public Administration; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.R.; During, D.W.; Selden, S. Q methodology. In Handbook of Research Methods in Public Administration; Miller, G.J., Whicker, M.L., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 589–637. [Google Scholar]

- Steelman, T.A.; Maguire, L.A. Understanding participant perspectives: Q-methodology in national forest management. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 1999, 18, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, H.; Jeffares, S.; Nichols, A.; Glasby, J. Beyond the Berlin Wall? Investigating joint commissioning and its various meanings using a Q methodology approach. Public Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 830–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A. The bones of a concourse. Operant Subj. 2004, 27, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, C.S. Types of important recognition on training counselors code of ethics. J. Learn.-Centered Curric. Instr. 2020, 20, 351–376. [Google Scholar]

- Sass, L. Embrace the Journey: Applying Q Methodology to Explore Induction Experiences of Teachers in Ohio Independent STEM Schools. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Findlay, Findlay, OH, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bublitz-Berg, E.; Platt, C.A.; Hill, B. Employee perceptions of responses to toxic leadership in the modern workplace: A Q methodological study. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2024, 45, 1205–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, S.; Stenner, P. The subjective experience of partnership love: A Q methodological study. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 44, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.E. Q Method & Sociology; Goldwell Publishing Inc.: Pusan, Republic of Korea, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.R. Political Subjectivity: Applications of Q Methodology in Political Science; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, C.; Stephenson, W. Alternative views on correlations between persons. Psychometrika 1939, 4, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, V.; Ostrom, E. Public goods and public choices. In Alternatives for Delivering Public Services; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; pp. 7–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chohan, U.W. Public Choice and Public Value. SSRN 2024. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4993588 (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Hallsworth, M.; Egan, M.; Rutter, J.; McCrae, J. Behavioural Government: Using Behavioural Science to Improve How Governments Make Decisions; The Behavioural Insights Team: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.bi.team/publications/behavioural-government/ (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Lee, A.; Choi, Y.; Kim, T.; Ahn, Y.; Ko, S. A Base Study for Social Policy Evaluations; [Research Report, No. 2021-11]; Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs: Sejong City, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negri, C.; Dincă, G. Public sector’s efficiency as a reflection of governance quality, a European Union study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0291048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, H. Optimizing government outsourcing: A performance management framework for enhancing public service delivery. J. Public Policy 2025, 45, 146–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benegrew, W.M. Public choice theory: Its application and challenges in the public sector. Int. J. Afr. Asian Stud. 2020, 66, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, A. Public Choice and Civil Society. SSRN 2024. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4914462 (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Towards a Framework for the Governance of Infrastructure; OECD: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Building Resilience to the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Centres of Government; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Recommendation of the Council on Human-Centred Public Administrative Services. In OECD Legal Instruments; OECD: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Blöchliger, H. Market Mechanisms in Public Service Provision, OECD Working Papers on Fiscal Federalism; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, S.; Wüstemann, H. Public governance of information asymmetries—The gap between reality and economic theory. J. Socio-Econ. 2010, 39, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, H.; Shah, N. Participatory budgeting: Models and approaches. In Pathways Between Social Science and Computational Social Science: Theories, Methods, and Interpretations; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 215–236. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, J.; Shephard, D.; Trnka, D. Behavioural Insight and Regulatory Governance: Opportunities and Challenges, OECD Regulatory Policy Working Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovens, M.; Zouridis, S. From street-level to system-level bureaucracies: How information and communication technology is transforming administrative discretion and constitutional control. Public Adm. Rev. 2002, 62, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, T.; Lægreid, P. Trust in government: The relative importance of service satisfaction, political factors, and demography. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2005, 28, 487–511. [Google Scholar]

- Boston, J. Assessing the options for combatting democratic myopia and safeguarding long-term interests. Futures 2021, 125, 102668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, A.M. Policy making for the long term in advanced democracies. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2016, 19, 433–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, R.Ø.; Sørensen, E.; Torfing, J. Drivers of collaborative governance for the green transition. Public Manag. Rev. 2024, 26, 3715–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, A. A symposium on the behavioural limits of the state. Behav. Public Policy 2023, 7, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cookson, R.; Griffin, S.; Norheim, O.F.; Culyer, A.J.; Chalkidou, K. Distributional cost-effectiveness analysis comes of age. Value Health 2021, 24, 118–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step | Procedure |

|---|---|

| Q concourse | 399 literature research review collection |

| Q sample | 39 statements extracted |

| P sample | 25 participants selected |

| Q sorting | Forced distribution via www.qmethodsoftware.com |

| Data analysis | Ken Q Analysis (v1.3.1) |

| Content | Factor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Eigenvalue | 9.249 | 2.879 | 2.022 | 1.379 |

| Explained Variance (%) | 37 | 12 | 8 | 6 |

| Cumulative Variance (%) | 37 | 49 | 57 | 63 |

| Factors | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.000 | |||

| 2 | 0.4101 | 1.000 | ||

| 3 | −0.1451 | 0.1038 | 1.000 | |

| 4 | 0.5651 | 0.5512 | −0.1912 | 1.000 |

| Type | P Sample | Factor Loading | Affiliated Sector(s) | Years of Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 N = 8 | P3 | 10.000 | Policy, External Collaboration | More than 11 years |

| P15 | 5.754 | Policy, Planning and Operations, Programme Delivery, External Collaboration, Expert, Other | 6~10 years | |

| P13 | 4.493 | Expert | 6~10 years | |

| P21 | 4.346 | Policy, Planning and Operations, Programme Delivery, External Collaboration, Expert | 6~10 years | |

| P8 | 3.745 | Policy, Planning and Operations, Programme Delivery, External Collaboration, Expert | 6~10 years | |

| P5 | 3.425 | Planning and Operations | Less than 1 year | |

| P10 | 2.354 | Service User | N/A | |

| P7 | 1.859 | Policy, Planning and Operations | Less than 1 year | |

| Type 2 N = 8 | P6 | 10.069 | Planning and Operations | 6~10 years |

| P25 | 8.471 | External Collaboration Expert | N/A | |

| P17 | 5.366 | Service User | N/A | |

| P4 | 4.042 | Programme Delivery, Other | Less than 1 year | |

| P2 | 3.780 | Service User | N/A | |

| P16 | 3.585 | Planning and Operations, Expert | More than 11 years | |

| P24 | 2.752 | Policy, Planning and Operations, Programme Delivery, External Collaboration, Expert | More than 11 years | |

| P20 | 2.336 | Policy, Planning and Operations, Programme Delivery, External Collaboration, Expert | 6~10 years | |

| Type 3 N = 3 | P1 | 6.868 | Service User | N/A |

| P11 | 4.769 | Service User | N/A | |

| P22 | 3.602 | Service User | N/A | |

| Type 4 N = 6 | P9 | 6.304 | Policy | Less than 1 year |

| P12 | 3.233 | Policy | 1~3 years | |

| P18 | 2.951 | Planning and Operations, Programme Delivery, External Collaboration | More than 11 years | |

| P23 | 2.835 | Policy | 1~3 years | |

| P14 | 2.081 | Policy, Planning and Operations, External Collaboration | More than 11 years | |

| P19 | 1.724 | Planning and Operations, External Collaboration | More than 11 years |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, M.H.; Yi, J.S.; Shin, S.J.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, Y.C.; Lee, S.Y. Stakeholders’ Perceptions of the Nature-Based Healing Industry in South Korea: A Q Methodology Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1990. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161990

Yu MH, Yi JS, Shin SJ, Kim JS, Kim JH, Kim YC, Lee SY. Stakeholders’ Perceptions of the Nature-Based Healing Industry in South Korea: A Q Methodology Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(16):1990. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161990

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Moon Hee, Ji Seong Yi, Seo Jung Shin, Jae Soo Kim, Jeong Hyun Kim, Yu Cheon Kim, and Song Yi Lee. 2025. "Stakeholders’ Perceptions of the Nature-Based Healing Industry in South Korea: A Q Methodology Study" Healthcare 13, no. 16: 1990. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161990

APA StyleYu, M. H., Yi, J. S., Shin, S. J., Kim, J. S., Kim, J. H., Kim, Y. C., & Lee, S. Y. (2025). Stakeholders’ Perceptions of the Nature-Based Healing Industry in South Korea: A Q Methodology Study. Healthcare, 13(16), 1990. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161990