Quality of Life, Anxiety, and Depression in Caregivers of Community-Dwelling Heart Failure Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design, Setting, and Period of the Study

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria of the Sample

2.3. Data Collection and Procedure

2.4. Research Instrument

2.4.1. Measurement of Caregivers’ QoL (SF36)

2.4.2. Measurement of Anxiety and Depression (HADs)

2.4.3. Measurement of Patients’ Self-Care

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description (Caregivers)

3.2. Sample Description (Patients)

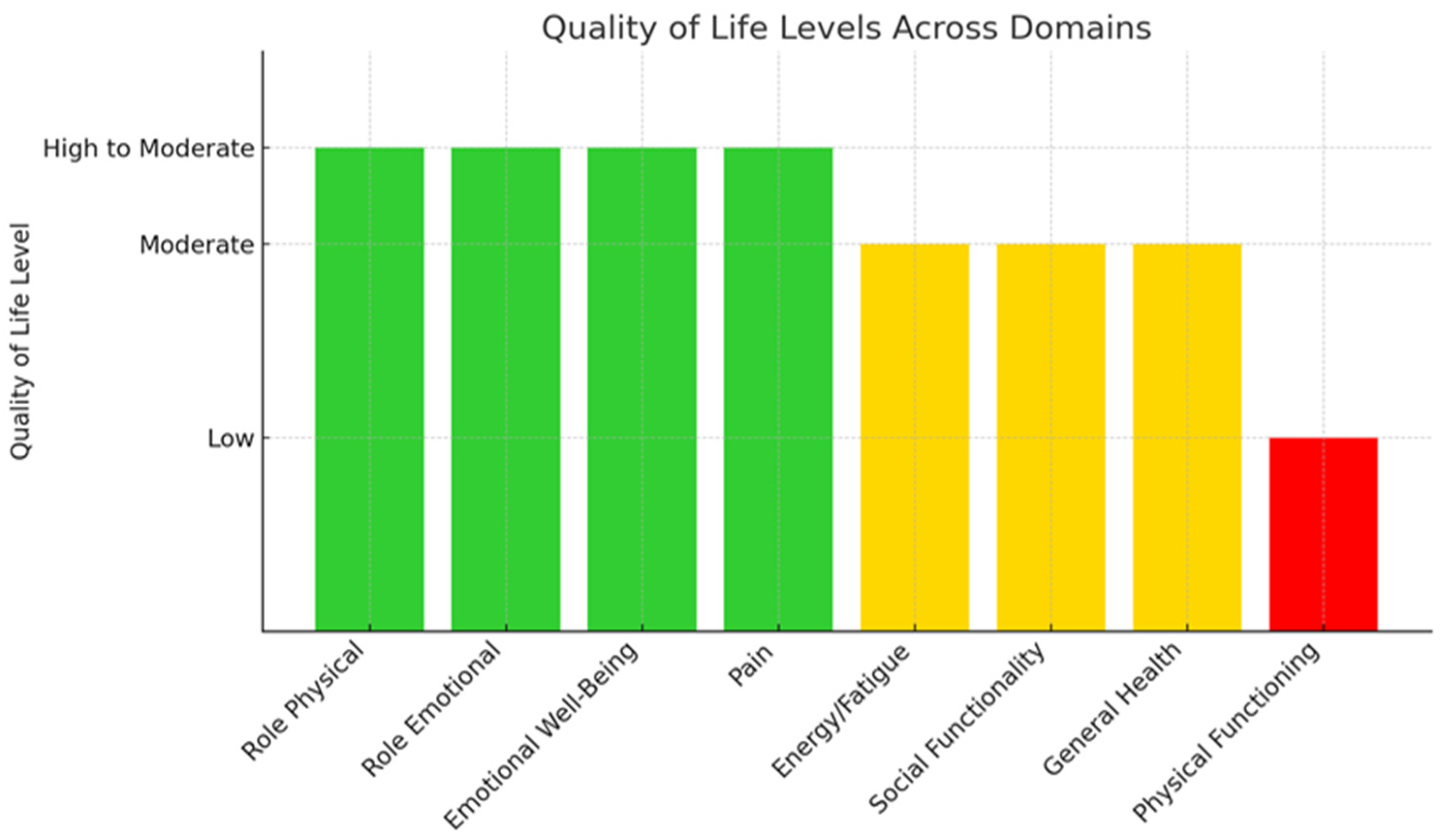

3.3. Caregivers’ QoL

3.4. Anxiety/Depression Among HF Caregivers and Their Patients

3.5. Patient’s Self-Care Behavior

3.6. Caregiver-Related Factors Associated with Caregivers’ QoL

3.7. Patient-Related Factors Associated with Caregivers’ QoL

3.8. Effect of Characteristics on Caregiver’s QoL

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

6. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kitko, L.; McIlvennan, C.K.; Bidwell, J.T.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Dunlay, S.M.; Lewis, L.M.; Meadows, G.; Sattler, E.L.P.; Schulz, R.; Strömberg, A.; et al. Family Caregiving for Individuals with Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 141, e864–e878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarese, G.; Becher, P.M.; Lund, L.H.; Seferovic, P.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Coats, A.J.S. Global burden of heart failure: A comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 118, 3272–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidwell, J.T.; Lyons, K.S.; Cs, L. Caregiver well-being and patient outcomes in heart failure: A meta-analysis. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2017, 32, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahoz, R.; Proudfoot, C.; Fonseca, A.F.; Loefroth, E.; Corda, S.; Jackson, J.; Cotton, S.; Studer, R. Caregivers of Patients with Heart Failure: Burden and the Determinants of Health-Related Quality of Life. Patient Prefer Adherence 2021, 15, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bueno, H.; Cleland, J.G.; Coats, A.J.; Falk, V.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Harjola, V.P.; Jankowska, E.A.; et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2016, 18, 891–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingham, J.; Frost, J.; Britten, N. Behind the smile: Qualitative study of caregivers’ anguish and management responses while caring for someone living with heart failure. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buck, H.G.; Howland, C.; Stawnychy, M.A.; Aldossary, H.; Cortés, Y.I.; DeBerg, J.; Durante, A.; Graven, L.J.; Irani, E.; Jaboob, S.; et al. Caregivers’ Contributions to Heart Failure Self-care: An Updated Systematic Review. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2024, 39, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suksatan, W.; Tankumpuan, T.; Davidson, P.M. Heart Failure Caregiver Burden and Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J. Prim. Care Commun. Health 2022, 13, 21501319221112584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilotra, N.A.; Pamboukian, S.V.; Mountis, M.; Robinson, S.W.; Kittleson, M.; Shah, K.B.; Forde-McLean, R.C.; Haas, D.C.; Horstmanshof, D.A.; Jorde, U.P.; et al. Caregiver Health-Related Quality of Life, Burden, and Patient Outcomes in Ambulatory Advanced Heart Failure: A Report From REVIVAL. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e019901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Vatovec, C.; Reblin, M. Caregiving in rural areas: A qualitative study of challenges and resilience. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0325536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yu, L.; Zhu, L.; Li, L.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, T.; Gu, D. Effects of home disease management strategies based on the dyadic illness management theory on elderly patients with chronic heart failure and informal caregivers’ physical and psychological outcomes: Protocol of a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2024, 25, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, M.S.; Do Prado, P.R.; de Barros, A.L.B.L.; de Lima Lopes, J. Depressive symptoms in the family caregivers of patients with heart failure: An integrative review. Rev. Gauch. Enferm. 2019, 40, e20180057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clements, L.; Frazier, S.K.; Moser, D.K.; Lennie, T.A.; Chung, M.L. The Mediator Effects of Depressive Symptoms on the Relationship between Family Functioning and Quality of Life in Caregivers of Patients with Heart Failure. Heart Lung 2020, 49, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrer, S.; Heyman, B. Sampling in epidemiological research: Issues, hazards and pitfalls. BJPsych Bull. 2016, 40, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, J.E. SF-36 health survey update. Spine 2000, 25, 3130–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, E.; Kontodimopoulos, N.; Niakas, D. Validating and norming of the Greek SF-36 Health Survey. Qual. Life Res. 2005, 14, 1433–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michopoulos, I.; Douzenis, A.; Kalkavoura, C.; Christodoulou, C.; Michalopoulou, P.; Kalemi, G.; Fineti, K.; Patapis, P.; Protopapas, K.; Lykouras, L. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADs): Validation in a Greek general hospital sample. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2008, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrinou, E.; Kalogirou, F.; Lamnisos, D.; Papathanassoglou, E.; Protopapas, A.; Sourtzi, P.; Barberis, V.I.; Lemonidou, C.; Antoniades, L.C.; Middleton, N. The Greek version of the 9-item European Heart Failure Self-care Behaviour Scale: A multidimensional or a uni-dimensional scale? Heart Lung 2014, 43, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsami, A.; Koutelekos, I.; Gerogianni, G.; Vasilopoulos, G.; Pavlatou, N.; Kalogianni, A.; Kapadochos, T.; Stamou, A.; Polikandrioti, M. Quality of Life in Heart Failure Patients: The Effect of Anxiety and Depression (Patient-Caregiver) and Caregivers’ Quality of Life. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polikandrioti, M.; Tsami, A. Factors Affecting Quality of Life of Caregivers of Patients with Heart Failure. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzo, A.; Biagioli, V.; Durante, A.; Emberti Gialloreti, L.; D’Agostino, F.; Alvaro, R.; Vellone, E. Influence of preparedness on anxiety, depression, and quality of life in caregivers of heart failure patients: Testing a model of path analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, M.L.; Pressler, S.J.; Dunbar, S.B.; Lennie, T.A.; Moser, D.K. Predictors of depressive symptoms in caregivers of patients with heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2010, 25, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petty, M.G.; Wu, T.; Andrei, A.C.; Baldridge, A.; Warzecha, A.; Kao, A.; Spertus, J.; Hsich, E.; Dew, M.A.; Pham, D.; et al. Baseline Quality-of-Life of Caregivers of Patients With Heart Failure Prior to Advanced Therapies: Findings From the Sustaining Quality of Life of the Aged: Transplant or Mechanical Support (SUSTAIN-IT) Study. J. Card. Fail. 2022, 28, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niitani, M.; Sawatari, H.; Takei, Y.; Yamashita, N. Associated Factors for Quality of Life, Anxiety, and Depression in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure and Their Family Caregivers: A Cross-Sectional Study in Japan. Palliat. Med. Rep. 2024, 5, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljeroos, M.A.; Miller, J.L.; Lennie, T.A.; Chung, M.L. Quality of life and family function are poorest when both patients with heart failure and their caregivers are depressed. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2022, 21, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, K.H.; Shin, M.S.; Heo, S.; Lee, J.A.; Cho, K.; An, M. Evaluating dyadic factors associated with self-care in patients with heart failure and their family caregivers: Using an Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0308515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.; Datti, R.S.; Tewari, A.; Sirisety, M. Exploring the positive aspects of caregiving among family caregivers of the older adults in India. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1059459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinkels, J.C.; van Tilburg, T.G.; Broese van Groenou, M. Why do spouses provide personal care? A study among care-receiving Dutch community-dwelling older adults. Health Soc. Care Commun. 2022, 30, e953–e961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subih, M.; AlBarmawi, M.; Bashir, D.Y.; Jacoub, S.M.; Sayyah, N.S. Correlation between quality of life of cardiac patients and caregiver burden. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśnicka, A.; Lomper, K.; Uchmanowicz, I. Self-care and quality of life among men with chronic heart failure. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 942305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellafiore, F.; Arrigoni, C.; Pittella, F.; Conte, G.; Magon, A.; Caruso, R. Paradox of self-care gender differences among Italian patients with chronic heart failure: Findings from a real-world cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, B.J.; Marcuccilli, L.; Sloan, R.; Gradus-Pizlo, I.; Bakas, T.; Jung, M.; Pressler, S.J. Competence, Compassion, and Care of the Self: Family Caregiving Needs and Concerns in Heart Failure. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2016, 31, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalhor, F.; Shahzeydi, A.; Taghadosi, M. The impact of home care on individuals with chronic heart failure: A comprehensive review. ARYA Atheroscler. 2024, 20, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco Barzallo, D.; Schnyder, A.; Zanini, C.; Gemperli, A. Gender Differences in Family Caregiving. Do female caregivers do more or undertake different tasks? BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, P.; Pérez-Esteve, C.; Sánchez-García, A.; Gil-Hernández, E.; Guilabert, M.; Mira, J.J. Understanding the Roles of over 65-Year-Old Male and Female Carers: A Comparative Analysis of Informal Caregiving. Geriatrics 2025, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Relation to patient | |

| Child | 45 (40%) |

| Spouse | 65 (60%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 31 (28.2%) |

| Female | 79 (71.8%) |

| Age (years) | |

| <40 | 21 (19.1%) |

| 41–50 | 24 (21.8%) |

| 51–60 | 30 (27.3%) |

| >60 | 35 (31.8%) |

| Education | |

| Primary | 26 (23.6%) |

| Secondary | 39 (35.5%) |

| University | 37 (33.6%) |

| MSc or PhD | 8 (7.3%) |

| Occupation | |

| Employed | 63 (57.3%) |

| Household | 21 (19.0%) |

| Pensioner | 26 (23.7%) |

| Residency | |

| Attica | 64 (58.2%) |

| Prefecture capital | 24 (21.8%) |

| Province | 22 (20.0%) |

| Νο of Children | |

| 0 | 31 (28.2%) |

| 1 | 24 (21.8%) |

| 2 | 40 (36.4%) |

| >2 | 15 (13.6%) |

| Need for written HF information (yes) | 95 (87.2%) |

| Are you informed about the patient’s self-care | |

| Very informed | 48 (43.6%) |

| Informed enough | 41 (37.3%) |

| A little informed | 21 (19.1%) |

| Not informed at all | 0 (0.0%) |

| Do you support the patient in daily management tasks? | |

| Always | 42 (38.2%) |

| Often | 38 (34.5%) |

| Rarely | 24 (21.8%) |

| Never | 6 (5.5%) |

| Do you neglect your own health? | |

| Always | 28 (25.5%) |

| Often | 44 (40.0%) |

| Rarely | 26 (23.6%) |

| Never | 12 (10.9%) |

| Do you participate in medical decision making? | |

| Always | 28 (25.5%) |

| Often | 61 (55.5%) |

| Rarely | 17 (15.5%) |

| Never | 4 (3.5%) |

| Need to learn new skills? (yes) | 81 (75.0%) |

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 73 (66.4%) |

| Female | 37 (33.6%) |

| Age (years) | |

| 41–50 | 6 (5.4%) |

| 51–60 | 15 (13.6%) |

| 61–70 | 28 (25.5%) |

| >70 | 61 (55.5%) |

| NYHA | |

| II | 21 (19.1%) |

| III | 48 (43.6%) |

| IV | 41 (37.3%) |

| Education | |

| Primary | 56 (50.9%) |

| Secondary | 36 (32%) |

| University | 14 (12.7%) |

| MSc or PhD | 4 (3.6%) |

| Occupation | |

| Employed | 14 (12.7%) |

| Household | 27 (24.5%) |

| Pensioner | 69 (62.8%) |

| Residency | |

| Attica | 60 (54.5%) |

| Prefecture capital | 36 (32.7%) |

| Province | 14 (12.7%) |

| Need for written HF information (yes) | 78 (70.9%) |

| Need to learn new skills? (yes) | 53 (58.2%) |

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Cronbach’s a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning (Range: 0–100) | 19.13 (8.40) | 18.0 (10.0–26.0) | 0.789 |

| Role-physical (Range: 0–100) | 60.00 (40.81) | 75.0 (25.0–100.0) | 0.850 |

| Role-emotional (Range: 0–100) | 56.97 (39.45) | 66.7 (33.3–100.0) | 0.718 |

| Energy/fatigue (Range: 0–100) | 53.76 (24.31) | 55.0 (35.0–75.0) | 0.893 |

| Emotional well-being (Range: 0–100) | 58.65 (23.76) | 64.0 (36.0–80.0) | 0.923 |

| Social functioning (Range: 0–100) | 57.50 (31.00) | 56.3 (25.0–87.5) | 0.883 |

| Pain (Range: 0–100) | 61.93 (31.62) | 67.5 (32.5–90.0) | 0.913 |

| General health (Range: 0–100) | 54.61 (21.75) | 62.0 (37.0–72.0) | 0.900 |

| Physical Component Summary (PCS) | 35.25 (6.48) | 35.9 (30.1–40.1) | |

| Mental Component Summary (MCS) | 46.40 (14.52) | 47.5 (33.6–59.4) |

| Patients n (%) | Caregivers n (%) | Cronbach’s a (Patients/Caregivers) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 0.868 (patients) 0.830 (caregivers) | ||

| No (Score ≤ 8) | 48 (43.6%) | 39 (35.5%) | |

| Yes (Score > 8) | 62 (56.4%) | 71 (64.5%) | |

| Depression | 0.857 (patients) 0.897 (caregivers) | ||

| No (Score ≤ 8) | 45 (40.9%) | 64 (58.2%) | |

| Yes (Score > 8) | 65 (59.1%) | 46 (41.8%) |

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Cronbach’s a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Self-Care Behavior (Range 9–45) | 19.57 (6.95) | 17.5 (14.0–23.0) | 0.775 |

| Caregiver Physical Component Summary (SF36-PCS) | Caregiver Mental Component Summary (SF36-MCS) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver’s Characteristics | Mean | Median | p-Value # | Mean | Median | p-Value # |

| (SD) | (IQR) | (SD) | (IQR) | |||

| Relation to patient | 0.001 * | 0.003 * | ||||

| Child | 38.29 (6.36) | 39.0 (37.0–41.1) | 51.19 (13.74) | 54.8 (41.1–63.4) | ||

| Spouse | 32.91 (5.72) | 33.5 (29.0–35.8) | 41.89 (14.38) | 38.8 (29.6–54.2) | ||

| Gender | 0.001 * | 0.012 * | ||||

| Male | 38.49 (5.85) | 40.1 (36.2–41.3) | 51.66 (14.41) | 56.7 (43.7–63.4) | ||

| Female | 33.96 (6.30) | 34.3 (28.9–38.7) | 44.31 (14.11) | 44.1 (32.6–55.5) | ||

| Age (years) | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | ||||

| ≤40 | 37.59 (6.89) | 39.0 (38.3–41.1) | 56.43 (13.98) | 63.6 (45.2–65.3) | ||

| 41–50 | 39.22 (6.07) | 40.3 (35.6–42.0) | 48.54 (12.49) | 49.3 (42.4–56.1) | ||

| 51–60 | 35.89 (4.48) | 36.2 (31.8–38.6) | 47.76 (12.72) | 51.8 (37.3–59.0) | ||

| >60 | 30.21 (4.89) | 29.3 (26.3–33.7) | 36.91 (12.52) | 32.8 (28.4–43.9) | ||

| Education | 0.061 | 0.054 | ||||

| Primary | 31.59 (5.57) | 32.8 (29.1–34.4) | 36.51 (12.03) | 36.3 (25.4–38.9) | ||

| Secondary | 35.86 (6.22) | 36.2 (30.6–39.8) | 40.81 (13.91) | 41.2 (32.6–56.1) | ||

| University/MSc or PhD | 37.77 (5.30) | 38.9 (35.5–41.1) | 43.97 (11.41) | 45.5 (40.8–64.2) | ||

| Occupation | 0.062 | 0.059 | ||||

| Household | 32.75 (5.96) | 33.5 (28.4–37.4) | 44.50 (14.35) | 38.9 (32.6–58.2) | ||

| Employed | 35.59 (5.81) | 35.7 (33.6–41.0) | 47.09 (13.47) | 48.9 (41.1–61.6) | ||

| Pensioner | 30.81 (6.09) | 29.0 (26.8–33.7) | 39.94 (13.50) | 38.6 (25.4–42.8) | ||

| Residency | 0.004 * | 0.010 * | ||||

| Attica | 36.67 (6.02) | 37.9 (32.4–40.4) | 49.95 (13.58) | 51.8 (40.0–62.3) | ||

| Prefecture capital | 35.08 (6.72) | 35.9 (29.8–39.8) | 42.27 (14.33) | 38.6 (31.7–55.8) | ||

| Province | 31.40 (6.31) | 30.4 (26.3–35.9) | 40.61 (15.14) | 35.1 (28.4–53.9) | ||

| Νο of Children | 0.037 * | 0.002 * | ||||

| 0 | 37.72 (6.68) | 39.0 (36.2–41.0) | 53.22 (15.17) | 61.8 (43.7–64.8) | ||

| 1 | 35.11 (5.99) | 35.3 (30.7–39.1) | 48.43 (13.97) | 53.3 (38.6–58.7) | ||

| 2 | 34.15 (6.68) | 34.9 (29.0–39.8) | 41.52 (12.87) | 38.9 (30.8–53.4) | ||

| >2 | 33.39 (5.37) | 32.1 (28.8–36.2) | 42.04 (13.16) | 40.8 (32.3–53.5) | ||

| Informed about patient’s self-care | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | ||||

| Very informed | 37.65 (5.88) | 38.9 (35.5–41.1) | 52.56 (13.61) | 56.7 (44.9–64.2) | ||

| Informed enough | 34.68 (5.83) | 34.6 (30.2–39.0) | 44.75 (13.53) | 45.2 (35.2–55.5) | ||

| A little informed | 30.98 (6.80) | 28.9 (26.1–34.4) | 35.82 (11.54) | 32.3 (28.4–43.3) | ||

| Need for written info about HF | 0.107 | 0.067 | ||||

| Yes | 34.88 (6.55) | 35.7 (29.3–39.9) | 45.56 (14.26) | 46.2 (32.8–58.2) | ||

| No | 37.73 (5.60) | 39.0 (34.6–40.7) | 52.10 (15.47) | 56.3 (40.0–64.8) | ||

| Need for learning new skills? | 0.005 * | 0.001 * | ||||

| Yes | 34.32 (6.58) | 34.6 (29.0–39.0) | 42.81 (13.63) | 43.1 (32.3–54.2) | ||

| No | 38.06 (5.37) | 39.3 (37.0–40.7) | 57.30 (11.50) | 62.3 (52.8–65.4) | ||

| Do you support the patient in daily management tasks? | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | ||||

| Always | 32.54 (6.89) | 30.7 (26.8–36.7) | 36.81 (12.92) | 33.9 (25.1–48.1) | ||

| Often | 34.99 (5.65) | 35.9 (31.4–38.9) | 47.89 (12.04) | 50.8 (37.2–57.3) | ||

| Rarely | 39.35 (4.65) | 40.1 (38.5–41.1) | 57.98 (9.69) | 62.0 (48.3–65.5) | ||

| Do you neglect your own health? | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | ||||

| Always | 31.88 (7.03) | 31.2 (26.3–35.8) | 36.67 (12.92) | 32.6 (25.3–50.3) | ||

| Often | 35.60 (5.57) | 36.2 (30.6–39.8) | 45.00 (12.36) | 45.2 (35.9–54.9) | ||

| Rarely | 37.32 (6.19) | 38.8 (34.2–40.7) | 55.14 (12.94) | 61.7 (50.2–64.7) | ||

| Do you participate in medical decision making? | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | ||||

| Always | 30.96 (6.96) | 29.1 (26.3–34.5) | 35.14 (12.90) | 31.9 (25.0–39.4) | ||

| Often | 36.83 (5.34) | 38.6 (33.5–40.3) | 49.00 (12.96) | 50.7 (39.1–58.7) | ||

| Rarely | 36.44 (6.56) | 37.1 (31.6–40.4) | 53.97 (12.62) | 59.5 (43.3–63.3) | ||

| Caregiver HADs: anxiety | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | ||||

| No (Score ≤ 8) | 38.3 (3.2) | 38.9 (36.7–40.4) | 58.9 (7.0) | 59.8 (54.5–64.8) | ||

| Yes (Score > 8) | 33.6 (7.2) | 32.0 (28.4–39.0) | 39.7 (13.0) | 37.3 (29.9–48.3) | ||

| Caregiver HADs: depression | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | ||||

| No (Score ≤ 8) | 38.5 (5.2) | 39.0 (36.7–41.1) | 54.6 (11.2) | 57.3 (47.7–63.9) | ||

| Yes (Score > 8) | 30.8 (5.2) | 30.6 (26.6–34.6) | 35.1 (10.4) | 33.2 (26.3–41.1) | ||

| Caregiver Physical Component Summary (SF36-PCS) | Caregiver Mental Component Summary (SF36-MCS) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient’s Characteristic | Mean | Median | p-Value # | Mean | Median | p-Value # |

| (SD) | (IQR) | (SD) | (IQR) | |||

| Gender | 0.035 * | 0.875 | ||||

| Male | 34.5 (6.2) | 35.6 (29.3–38.9) | 46.5 (15.0) | 49.1 (32.6–60.5) | ||

| Female | 36.7 (6.8) | 39.8 (30.6–41.3) | 46.2 (13.7) | 45.8 (36.3–57.4) | ||

| Age | 0.128 | 0.659 | ||||

| ≤60 | 35.2 (6.6) | 35.7 (29.4–40.7) | 45.9 (15.8) | 52.3 (32.3–57.4) | ||

| 61–70 | 33.5 (5.7) | 32.9 (28.9–37.2) | 44.8 (12.5) | 45.0 (36.5–54.5) | ||

| >70 | 36.1 (6.7) | 37.4 (30.6–40.3) | 47.3 (15.1) | 47.9 (35.1–61.7) | ||

| Education | 0.670 | 0.801 | ||||

| Primary | 35.1 (6.9) | 36.1 (28.9–40.1) | 45.7 (15.2) | 46.5 (31.7–59.8) | ||

| Secondary | 35.8 (6.7) | 37.1 (30.5–41.0) | 47.8 (13.8) | 50.5 (36.3–61.6) | ||

| University/MSc/PhD | 34.6 (4.8) | 34.8 (30.8–38.2) | 45.9 (14.2) | 50.3 (33.6–56.1) | ||

| Occupation | 0.089 | 0.029 * | ||||

| Employed | 35.1 (5.4) | 35.7 (30.7–39.0) | 49.1 (13.6) | 52.8 (37.3–59.4) | ||

| Pensioner | 36.0 (6.8) | 37.1 (31.1–40.3) | 47.1 (14.6) | 47.6 (35.1–60.8) | ||

| Household | 31.3 (5.8) | 29.1 (26.8–36.0) | 36.1 (12.5) | 34.1 (26.3–44.0) | ||

| Residency | 0.67 | 0.801 | ||||

| Attica | 35.1 (6.9) | 36.1 (28.9–40.1) | 45.7 (15.2) | 46.5 (31.7–59.8) | ||

| Prefecture capital | 35.8 (6.7) | 37.1 (30.5–41.0) | 47.8 (13.8) | 50.5 (36.3–61.6) | ||

| Province | 34.6 (4.8) | 34.8 (30.8–38.2) | 45.9 (14.2) | 50.3 (33.6–56.1) | ||

| NYHA | 0.433 | 0.138 | ||||

| I-II | 34.6 (6.3) | 34.6 (29.0–39.0) | 47.1 (13.1) | 44.9 (36.1–55.5) | ||

| III | 36.4 (6.5) | 37.1 (30.7–40.3) | 49.2 (13.5) | 51.2 (36.8–60.9) | ||

| IV | 34.2 (6.5) | 35.6 (28.4–39.6) | 42.7 (15.9) | 41.9 (25.7–57.1) | ||

| Need for written information | 0.752 | 0.200 | ||||

| Yes | 35.2 (6.6) | 35.5 (30.2–40.1) | 45.3 (13.9) | 46.2 (33.6–56.7) | ||

| No | 35.3 (6.3) | 38.2 (29.2–40.1) | 49.0 (15.8) | 53.7 (35.5–63.2) | ||

| Need for learning new skills | 0.100 | 0.705 | ||||

| Yes | 34.1 (6.1) | 34.9 (28.9–39.0) | 46.9 (15.0) | 48.3 (32.6–61.6) | ||

| No | 36.4 (6.7) | 37.2 (30.6–40.3) | 45.9 (14.1) | 46.7 (35.7–58.3) | ||

| Patient HADs: anxiety | 0.985 | 0.453 | ||||

| No (Score ≤ 8) | 35.4 (6.5) | 35.6 (30.4–39.2) | 47.8 (13.1) | 47.6 (35.6–60.3) | ||

| Yes (Score > 8) | 35.1 (6.5) | 36.2 (29.4–40.3) | 45.3 (15.5) | 46.2 (32.3–59.4) | ||

| Patient HADs: depression | 0.502 | 0.059 | ||||

| No (Score ≤ 8) | 34.9 (6.0) | 34.9 (29.3–39.0) | 49.6 (13.5) | 54.1 (37.2–62.2) | ||

| Yes (Score > 8) | 35.5 (6.8) | 36.2 (30.4–40.3) | 44.1 (14.9) | 43.8 (31.9–56.4) | ||

| Spearman’s Rho | Spearman’s Rho | |||||

| Patient self-care behavior | −0.152 | 0.116 | −0.072 | 0.459 | ||

| Caregiver Physical Component Summary (SF36-PCS) # | Caregiver Mental Component Summary (SF36-MCS) # | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b coef (95% CI) | p-Value | b coef (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Caregiver (Spouse vs. Child) | −0.87 (−4.31–2.58) | 0.617 | 2.04 (−4.36–8.43) | 0.526 |

| Caregiver Gender (Female vs. Male) | −1.79 (−4.78–1.19) | 0.235 | −4.07 (−9.59–1.45) | 0.146 |

| Caregiver Age | ||||

| ≤40 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 41–50 | 2.94 (−0.87–6.74) | 0.128 | −5.92 (−12.65–0.81) | 0.084 |

| 51–60 | −1.54 (−5.85–2.77) | 0.478 | −4.22 (−11.73–3.29) | 0.265 |

| >60 | −3.39 (−8.69–1.92) | 0.207 | −7.96 (−17.35–1.43) | 0.095 |

| Caregiver Residency | ||||

| Attica | Ref | ref | ||

| Prefecture capital | 1.15 (−2.19–4.50) | 0.492 | −3.29 (−9.06–2.47) | 0.257 |

| Province | 1.33 (−2.31–4.98) | 0.468 | 1.64 (−4.41–7.69) | 0.59 |

| Caregiver Νο of Children | ||||

| 0 | Ref | ref | ||

| 1 | 2.91 (−1.91–7.73) | 0.232 | 3.67 (−4.57–11.90) | 0.377 |

| 2 | 3.17 (−0.81–7.15) | 0.116 | 2.72 (−4.34–9.78) | 0.443 |

| >2 | 4.49 (−0.59–9.58) | 0.082 | 3.52 (−5.35–12.39) | 0.431 |

| Caregiver is “informed about patient’s self-care” | ||||

| Very informed | Ref | ref | ||

| Informed enough | −0.66 (−3.86–2.54) | 0.683 | −0.22 (−5.84–5.39) | 0.937 |

| A little informed | 1.56 (−2.93–6.06) | 0.489 | 0.71 (−7.11–8.52) | 0.857 |

| Caregiver “needs to learn new skills” (no vs. yes) | 0.90 (−2.72–4.53) | 0.621 | −0.62 (−6.83–5.59) | 0.842 |

| Caregiver “supports patients in daily management tasks” | ||||

| Always | Ref | ref | ||

| Often | −0.05 (−3.35–3.24) | 0.974 | 4.25 (−1.93–10.44) | 0.174 |

| Rarely | 2.66 (−1.39–6.71) | 0.195 | 7.90 (0.49–15.30) | 0.037 * |

| Caregiver answers to “Do you neglect your own health?” | ||||

| Always | Ref | ref | ||

| Often | −0.09 (−3.64–3.45) | 0.958 | −4.62 (−12.91–3.66) | 0.269 |

| Rarely | −1.22 (−5.32–2.88) | 0.554 | −4.11 (−13.76–5.54) | 0.397 |

| Caregiver “participates in medical decision making” | ||||

| Always | - | ref | ||

| Often | - | 12.19 (3.23–21.14) | 0.009 * | |

| Rarely | - | 14.23 (4.15–24.31) | 0.006 * | |

| PatientOccupation | ||||

| Employed | - | ref | ||

| Pensioner | - | −4.07 (−9.72–1.58) | 0.155 | |

| Household | - | −7.17 (−15.27–0.94) | 0.082 | |

| Caregiver HADs: Anxiety (yes vs. no) | 0.59 (−2.58–3.77) | 0.71 | −9.27 (−14.87–3.68) | 0.002 * |

| Caregiver HADs: Depress. (yes vs. no) | −6.22 (−9.70-−2.73) | 0.001 * | −8.21 (−14.85–1.57) | 0.016 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Polikandrioti, M.; Tsami, A.; Tsoulou, V.; Maggita, A. Quality of Life, Anxiety, and Depression in Caregivers of Community-Dwelling Heart Failure Patients. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1986. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161986

Polikandrioti M, Tsami A, Tsoulou V, Maggita A. Quality of Life, Anxiety, and Depression in Caregivers of Community-Dwelling Heart Failure Patients. Healthcare. 2025; 13(16):1986. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161986

Chicago/Turabian StylePolikandrioti, Maria, Athanasia Tsami, Vasiliki Tsoulou, and Andriana Maggita. 2025. "Quality of Life, Anxiety, and Depression in Caregivers of Community-Dwelling Heart Failure Patients" Healthcare 13, no. 16: 1986. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161986

APA StylePolikandrioti, M., Tsami, A., Tsoulou, V., & Maggita, A. (2025). Quality of Life, Anxiety, and Depression in Caregivers of Community-Dwelling Heart Failure Patients. Healthcare, 13(16), 1986. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161986