Health Education in Mass Gatherings: A Scoping Review to Guide Public Health Preparedness and Practice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Stage 1: Identifying the Research Question

2.2. Stage 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

2.3. Stage 3: Study Selection

2.4. Study Eligibility Criteria

2.4.1. Population

2.4.2. Concept

2.4.3. Context

2.4.4. Type of Studies

2.5. Stage 4: Charting the Data

2.6. Stage 5: Collating, Summarising, and Reporting the Results

3. Results

3.1. This Study Selection Process

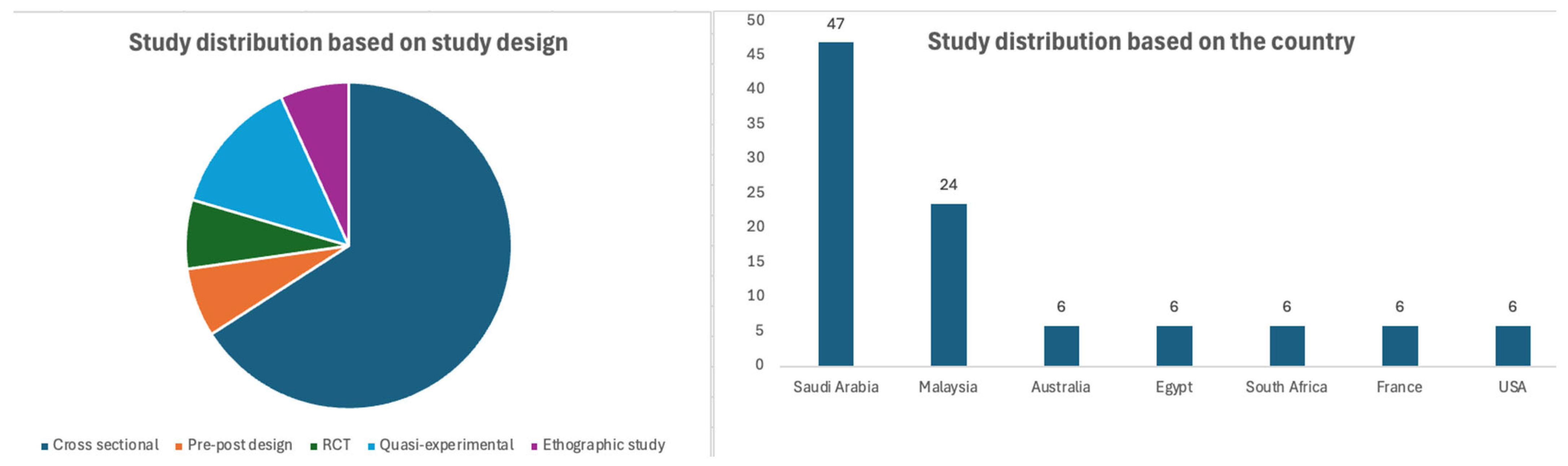

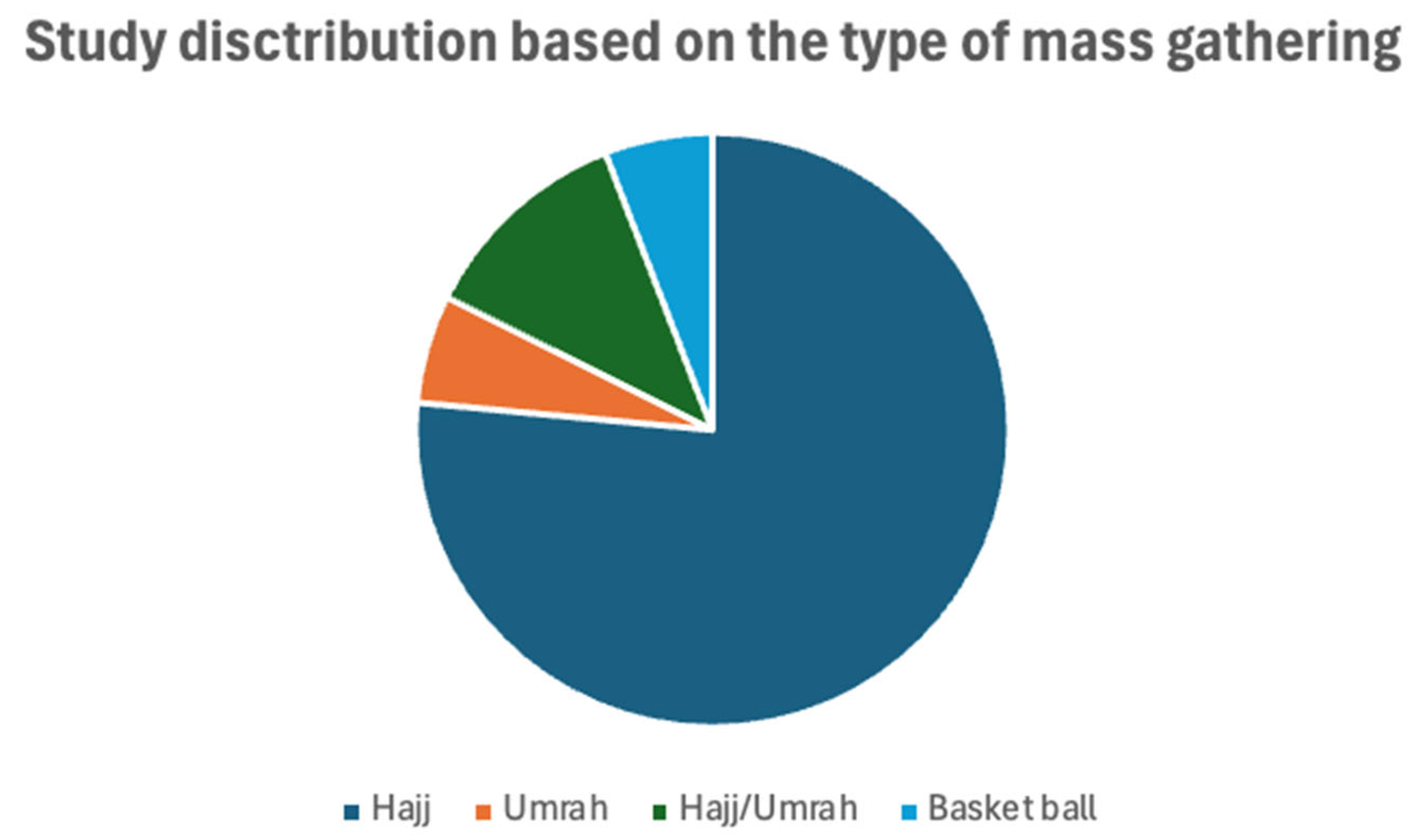

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Characteristics of Health Education

3.4. Details and Focus of the Health Education

3.5. Effectiveness of Health Education

3.5.1. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice

3.5.2. Vaccination

3.5.3. Compliance with the Use of Face Mask

3.5.4. Hand Hygiene

3.5.5. Respiratory Infections

3.5.6. Viral Infections

3.5.7. Asthma Education

3.5.8. Medication Storage

3.5.9. Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation (CPR)

3.5.10. Acceptance or Helpfulness of Health Education

3.6. Practice Implications

- Develop standardized content in collaboration with authorities: A standard health education package should be created with the Ministry of Health to ensure consistency. It could be shared via official travel websites and transportation systems (e.g., flights, buses, ships) [42].

3.7. Research Implications

- Conduct large, long-term comparative studies: There is a need for large-scale studies comparing the effectiveness of different education methods, especially in terms of long-term knowledge retention [44].

- Define what effective health education looks like: More research should clarify what constitutes effective health education for pilgrims. This should cover content, format, access, delivery, provider, language, and follow-up strategies [30].

- Understand pilgrims’ perceptions and knowledge gaps: Investigating pilgrims’ views will help identify knowledge gaps, which can inform the design of more targeted and effective education programs [32,48]. There is a lack of research evidence on how pilgrims perceive risks and adopt information, and how best to interact with their willingness to be trained in preventive measures [13].

4. Discussion

4.1. General Background of Discussion

4.2. Findings from the Evidence and Discussion

4.3. Limitations and Gaps

5. Conclusions

Deviation from the Registered Protocol

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| CDC | Center for Disease Control |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute’s |

| RCT | randomized controlled trial |

| CPR | Cardio-pulmonary resuscitation |

References

- World Health Organization. Public Health for Mass Gatherings: Key Considerations; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Halsey, E. CDC Yellow Book 2026: Health Information for International Travel; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Gautret, P.; Benkouiten, S.; Memish, Z.A. Mass Gatherings and the Spread of Respiratory Infections. Lessons from the Hajj. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 13, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, S.; Roy, N. Public health perspectives from the biggest human mass gathering on earth: Kumbh Mela, India. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 47, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.; Steffen, R.; Rashid, H.; Cabada, M.M.; A Memish, Z.; Gautret, P.; Sokhna, C.; Sharma, A.; Shlim, D.R.; Leshem, E.; et al. Sacred journeys and pilgrimages: Health risks associated with travels for religious purposes. J. Travel Med. 2024, 31, taae122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memish, Z.A.; Steffen, R.; White, P.; Dar, O.; Azhar, E.I.; Sharma, A.; Zumla, A. Mass gatherings medicine: Public health issues arising from mass gathering religious and sporting events. Lancet 2019, 393, 2073–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehning, J.; Mohr, S.B.; Contreras, S.; Dönges, P.; Iftekhar, E.N.; Schulz, O.; Bechtle, P.; Priesemann, V. Impact of the Euro 2020 championship on the spread of COVID-19. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.R. Health Communications Matter: A Comparative Case Study of Best Practices to Combat Misinformation and Disinformation During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dawood, H.N.; Al-Jumaili, A.H.; Radhi, A.H.; Ikram, D.; Al-Jabban, A. Emerging pneumococcal serotypes in Iraq: Scope for improved vaccine development. F1000Research 2023, 12, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegboye, O.; Alele, F.; Pak, A.; Alakunle, E.; Emeto, T.; Leggat, P.; Okeke, M. Monkeypox Outbreak 2022, from a Rare Disease to Global Health Emergence: Implications for Travellers. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2024, 1451, 355–368. [Google Scholar]

- Alhussaini, N.W.Z.; Elshaikh, U.A.M.; Hamad, N.A.; Nazzal, M.A.; Abuzayed, M.; Al-Jayyousi, G.F. A scoping review of the risk factors and strategies followed for the prevention of COVID-19 and other infectious diseases during sports mass gatherings: Recommendations for future FIFA World Cups. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1078834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Keim, M.; He, Y.; Mahany, M.; Yuan, Z. Reducing the risk of public health emergencies for the world’s largest mass gathering: 2010 World Exposition, Shanghai China. Disaster Health 2013, 1, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Almehmadi, M.; Alqahtani, J.S. Healthcare Research in Mass Religious Gatherings and Emergency Management: A Comprehensive Narrative Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridda, I.; Mansoor, S.; Briggs, R.; Gishe, J.; Aatmn, D. Preparedness for Mass Gathering During Hajj and Umrah. In Handbook of Healthcare in the Arab World; Laher, I., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton, A.; Ranse, J.; Munn, M.B. Developing Public Health Initiatives through Understanding Motivations of the Audience at Mass-Gathering Events. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2018, 33, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, V.L. Instrument development for health belief model constructs. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 1984, 6, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katatsky, M.E. The health belief model as a conceptual framework for explaining contraceptive compliance. Health Educ. Monogr. 1977, 5, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaccard, J. A theoretical analysis of selected factors important to health education strategies. Health Educ. Monogr. 1975, 3, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, L.; Villegente, J.; Loyal, D.; Ayav, C.; Kivits, J.; Rat, A. Tailored patient therapeutic educational interventions: A patient-centred communication model. Health Expect. 2022, 25, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, M., Jr.; Castro, F.G.; Strycker, L.A.; Toobert, D.J. Cultural adaptations of behavioral health interventions: A progress report. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 81, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranse, J.; Hutton, A.; Keene, T.; Lenson, S.; Luther, M.; Bost, N.; Johnston, A.N.B.; Crilly, J.; Cannon, M.; Jones, N.; et al. Health Service Impact from Mass Gatherings: A Systematic Literature Review. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2017, 32, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reghunath, S.R.; Rashid, M.; Chandran, V.P.; Thunga, G.; Shivashankar, K.; Acharya, L.D. Factors contributing to the adverse drug reactions associated with the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors: A scoping review. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2023, 17, 102790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prathiksha, A.S.; Shantaram, P.M.; Rashid, M.; Poojari, P.G.; Nair, S.; Acharya, L.D.; Thunga, G. Determinants of and barriers to diabetes care among patients with serious mental illness: A scoping review with recommendations. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2024, 18, 103139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, R.; Hanafi, N.S.; Hussein, N.; Lee, P.Y.; Ghazali, S.S.; Cheong, A.T.; Abu Bakar, A.I.; Samad, A.A.; Abdullah, S.; Pinnock, H.; et al. Hajj health examination for pilgrims with asthma in Malaysia: An ethnographic study. J. Glob. Health 2022, 12, 04023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.S.; Wiley, K.E.; Tashani, M.; Willaby, H.W.; Heywood, A.E.; BinDhim, N.F.; Booy, R.; Rashid, H. Exploring barriers to and facilitators of preventive measures against infectious diseases among Australian Hajj pilgrims: Cross-sectional studies before and after Hajj. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 47, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khamis, N.K. Epidemiological pattern of diseases and risk behaviors of pilgrims attending mina hospitals, hajj 1427 h (2007 g). J. Egypt. Public Health Assoc. 2008, 83, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tobaiqy, M.; Alhasan, A.H.; Shams, M.M.; Amer, S.A.; MacLure, K.; Alcattan, M.F.; Almudarra, S.S. Assessment of Preventative Measures Practice among Umrah Pilgrims in Saudi Arabia, 1440H-2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yezli, S.; Yassin, Y.; Mushi, A.; Balkhi, B.; Stergachis, A.; Khan, A. Medication Handling and Storage among Pilgrims during the Hajj Mass Gathering. Healthcare 2021, 9, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmuna, Z.; Hashim, S.; Hasan, H.; Abdul Aziz, A.; Nyi, N.N.; Mohamed, Z.; Harun, A.; Abdul Rahman, Z. Knowledge, perceptions and practices of Malaysian hajj pilgrims for prevention of influenza-like illness (ILI) in 2013 hajj season. IIUM Med. J. Malays. 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goni, M.D.; Hasan, H.; Naing, N.N.; Wan-Arfah, N.; Deris, Z.Z.; Arifin, W.N.; Baaba, A.A. Impact of a Health Education Intervention on the Incidence of Influenza-Like Illnesses (ILI) During Hajj via Smartphone Application. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2023, 25, 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushi, A.; Yassin, Y.; Khan, A.; Alotaibi, B.; Parker, S.; Mahomed, O.; Yezli, S. A Longitudinal Study Regarding the Health Profile of the 2017 South African Hajj Pilgrims. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yezli, S.; Yassin, Y.; Mushi, A.; Balkhi, B.; Khan, A.; Scaramuzza, A. Insulin Knowledge, Handling, and Storage among Diabetic Pilgrims during the Hajj Mass Gathering. J. Diabetes Res. 2021, 2021, 5596914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goni, M.D.; Naing, N.N.; Hasan, H.; Wan-Arfah, N.; Deris, Z.Z.; Arifin, W.N.; Baaba, A.A.; Adam, B.M.; Arshad, M.R. Effectiveness of a Novel Smartphone Health Education Intervention in Enhancing Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices for the Prevention of Respiratory Tract Infections Among Private Hajj Pilgrims from Malaysia. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 594204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, H.; Alqahtani, A.; Barasheed, O.; Alemam, A.; Alhakami, M.; Gadah, I.; Alkediwi, H.; Alzahrani, K.; Fatani, L.; Dahlawi, L.; et al. Hand Hygiene Knowledge and Practices among Domestic Hajj Pilgrims: Implications for Future Mass Gatherings Amidst COVID-19. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 5, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.S.; Althimiri, N.A.; BinDhim, N.F. Saudi Hajj pilgrims’ preparation and uptake of health preventive measures during Hajj 2017. J. Infect. Public Health 2019, 12, 772–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migault, C.; Kanagaratnam, L.; Hentzien, M.; Giltat, A.; Nguyen, Y.; Brunet, A.; Thibault, M.; Legall, A.; Drame, M.; Bani-Sadr, F. Effectiveness of an education health programme about Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus tested during travel consultations. Public Health 2019, 173, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beskind, D.L.; Stolz, U.; Thiede, R.; Hoyer, R.; Robertson, W.; Brown, J.; Ludgate, M.; Tiutan, T.; Shane, R.; McMorrow, D.; et al. Viewing an ultra-brief chest compression only video improves some measures of bystander CPR performance and responsiveness at a mass gathering event. Resuscitation 2017, 118, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barasheed, O.; Rashid, H.; Heron, L.; Ridda, I.; Haworth, E.; Nguyen-Van-Tam, J.; Dwyer, D.E.; Booy, R.; on behalf of the Hajj Research Team. Influenza vaccination among Australian Hajj pilgrims: Uptake, attitudes, and barriers. J. Travel Med. 2014, 21, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Turkestani, A.; Balahmar, M.; Ibrahem, A.; Moqbel, E.; Memish, Z. Using health educators to improve knowledge of healthy behaviour among Hajj 1432 (2011) pilgrims. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2013, 19 (Suppl. S2), S9–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, F.; Amer, S.; Alhraiwil, N. Knowledge and practice after health education program among Hajj 1438 H (2017) Pilgrims. Saudi Arabia J. Epidemiol. Health Care 2018, 1, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, A.L.; Ling, D.I.; Casey, E.K.; Toresdahl, B.G.; Gellhorn, A.C. Feasibility and impact of a musculoskeletal health for musicians (MHM) program for musician students: A randomized controlled pilot study. J. Hand Ther. 2021, 34, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fteiha, B.; Abul Al-Rub, T.; Schwartz, E.; Lachish, T. Morbidity among Arab-Israeli and Palestinian Hajj Pilgrims: A Prospective Study. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 104, 1596–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaei, A.; Mortazavi, S.M.; Shamspour, N.; Shushtarizadeh, N. Health knowledge, attitude and practice among Iranian pilgrims. Iran. Red. Crescent. Med. J. 2015, 17, e12863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alhajri, W.; Templeton, A.; Moore, A. Social norms and risks at mass gatherings: A systematic review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 88, 103586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.S.; Sheikh, M.; Wiley, K.; Heywood, A.E. Australian Hajj pilgrims’ infection control beliefs and practices: Insight with implications for public health approaches. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2015, 13, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, S.; Ba-Aoum, M.; Alganmi, N.; Showail, A. Modeling Infectious Disease Epidemics in Mass Religious Gatherings: A Systematic Review. ACM Trans. Model. Comput. Simul. 2025, 35, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Effective Media Communication During Public Health Emergencies: A WHO Handbook; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Das, T.; Holland, P.; Ahmed, M.; Husain, L. Sustainable development goal 3: Good health and well-being. In South-East Asia Eye Health: Systems, Practices, and Challenges; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Elendu, C.; Amaechi, D.C.; Okatta, A.U.; Amaechi, E.C.M.; Elendu, T.C.B.; Ezeh, C.P.M.; Elendu, I.D.B. The impact of simulation-based training in medical education: A review. Medicine 2024, 103, e38813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandran, V.P.; Balakrishnan, A.; Rashid, M.; Kulyadi, G.P.; Khan, S.; Devi, E.S.; Nair, S.; Thunga, G.; Rahman, M.S. Mobile applications in medical education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, P.J. Improving health literacy using the power of digital communications to achieve better health outcomes for patients and practitioners. Front. Digit. Health 2023, 5, 1264780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Ismagilova, E.; Hughes, D.L.; Carlson, J.; Filieri, R.; Jacobson, J.; Jain, V.; Karjaluoto, H.; Kefi, H.; Krishen, A.S.; et al. Setting the future of digital and social media marketing research: Perspectives and research propositions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 59, 102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsulami, A.; Sacgaca, L.; Pangket, P.; Pasay-An, E.; Al Amoudi, F.A.; Alreshidi, M.S.; Alrashedi, N.; Mostoles, R.; Buta, J.; Areola, B.; et al. Exploring the Relationship Between Knowledge, Attitudes, Self-Efficacy, and Infection Control Practices Among Saudi Arabian Nurses: A Multi-Center Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Árvavölgyi, B.; Sági, J. Pilgrimage and its perception in a local religious community. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2019, 7, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Albutti, A.; Mahdi, H.A.; Alwashmi, A.S.; Alfelali, M.; Barasheed, O.; Barnes, E.H.; Shaban, R.Z.; Booy, R.; Rashid, H. The relationship between hand hygiene and rates of acute respiratory infections among Umrah pilgrims: A pilot randomised controlled trial. J. Infect. Public Health 2024, 17 (Suppl. S1), 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegranzi, B.; Storr, J.; Dziekan, G.; Leotsakos, A.; Donaldson, L.; Pittet, D. The first global patient safety challenge “clean care is safer care”: From launch to current progress and achievements. J. Hosp. Infect. 2007, 65, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goni, M.D.; Hasan, H.; Wan-Arfah, N.; Naing, N.N.; Deris, Z.Z.; Arifin, W.N.; Baaba, A.A.; Aliyu, A.; Adam, B.M. Health Education Intervention as an Effective Means for Prevention of Respiratory Infections Among Hajj Pilgrims: A Review. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualls, N. Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza—United States, 2017; Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR); Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017; Volume 66. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D.; Page, S.J. Progress and prospects for event tourism research. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 593–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, R.; Hogerzeil, H.; Ross-Degnan, D. Ten recommendations to improve use of medicines in developing countries. Health Policy Plan. 2001, 16, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.L.; Walker, R.J.; Smalls, B.L.; Campbell, J.A.; Egede, L.E. Effective interventions to improve medication adherence in Type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. Diabetes Manag. 2014, 4, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wee, J.; Tan, X.R.; Gunther, S.H.; Ihsan, M.; Leow, M.K.S.; Tan, D.S.-Y.; Eriksson, J.G.; Lee, J.K.W. Effects of Medications on Heat Loss Capacity in Chronic Disease Patients: Health Implications Amidst Global Warming. Pharmacol. Rev. 2023, 75, 1140–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baomer, A.A.; el Bushra, H.E. Profile of diabetic Omani pilgrims to Mecca. East Afr. Med. J. 1998, 75, 211–214. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C.; Ackermann, B. Evidence-informed physical therapy management of performance-related musculoskeletal disorders in musicians. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, L.S.; Wasley, D.; Redding, E.; Atkins, L.; Perkins, R.; Ginsborg, J.; Williamon, A. Fit to Perform: A Profile of Higher Education Music Students’ Physical Fitness. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosset, M.; Baumann, E.; Altenmüller, E. A Longitudinal Study of Physical and Mental Health and Health-Related Attitudes Among Music Students: Potentials and Challenges for University Health Promotion Programs. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 885739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodwin, A.H.; Shimizu, R.; Travis, R., Jr.; James, K.J.; Banya, M.; Munson, M.R. A Systematic Review of Music-Based Interventions to Improve Treatment Engagement and Mental Health Outcomes for Adolescents and Young Adults. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2022, 40, 537–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Al-Zahrani, S.; Al-Qattan, M.M. “Outbreak” of hand injuries during Hajj festivities in Saudi Arabia. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1999, 43, 154–155. [Google Scholar]

| Author, Year | Country | Study Design | Type of Participants | Type of Health Education | No. of Participants | Pattern/Sources of Health Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ramli R, 2022 [27] | Malaysia | Ethnographic study | Hajj pilgrims | Optional asthma education as part of health examination conducted in 11 public and 2 primary clinics before hajj departure | NR | 16 educational sessions, including 1 on health |

| Alqahtani AS 2016 [28] | Australia | Cross-sections study | Hajj pilgrims | Pre-travel professional travel health advice | 236 | General practitioners (51%); specialist travel clinic (15%), specific hajj website (8%); ‘Smartraveller’ website (7%); not received (33%) |

| Khamis NK [28] | Egypt | Cross-sectional study | Hajj pilgrims | Pre-travel health education | 248 | 34.4% received health education |

| Tobaiqy M 2020 [30] | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional survey | Umrah pilgrims | Pre-travel health education | 1012 | Press and publications (9.7%); family and friends (12.5%); lectures (25.8%); social media (5%); travel clinics (13.2%); health care providers (12%); Saudi MoH website (1.6%); other websites (5.1%); other sources (18%) |

| Yezli S 2021 [31] | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional survey | Hajj pilgrims | Health education on medication handling and Storage | 1221 | Physicians (73.7%); pharmacists (39.4%); medication label itself (28.2%), internet and family members (6.6%) |

| Salmuna ZN 2019 [32] | Malaysia | Open label RCT | Hajj pilgrims | Health education on hand-hygiene | 500 (Int: 250; Cont: 250) | One-to-one education |

| Goni MD 2023 [33] | Malaysia | Quasi-experimental study | Hajj/Umrah pilgrims | Smartphone-based health education intervention guided by the Health Belief Model on prevention of influenza-like illnesses | 102 | Smartphone application |

| Mushi A 2021 [34] | South Africa | Cross-sectional survey | Hajj pilgrims | Pre-hajj training and health promotion | 1138 | In-person |

| Yezli S 2021 (2) [35] | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional survey | Diabetic hajj pilgrims | Education on insulin storage and handling | 227 | Any (83.6%); physician (77.8%); pharmacist (59.6%); label (5.3%); internet (8.2%); other (7.6%) |

| Goni MD 2021 [36] | Malaysia | Quasi experimental | Hajj/Umrah pilgrims | Smartphone-based health education intervention guided by the Health Belief Model on prevention of respiratory diseases | 130 | Smartphone application |

| Mahdi H 2020 [37] | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional survey | Hajj pilgrims | Pre-hajj health advice | 348 | Any health advice (75.6%); Doctors (11.1%); Special Hajj websites (18.8%); Tour groups (18.5%); Family and friends (30.1%); General websites (21.5%); and MoH recommendations (66.4%) |

| Alqahtani AS 2019 [38] | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional survey | Hajj pilgrims | Pretravel health-advice-seeking behavior | 344 | Any (44%); media sources (27.6%); travel clinic (14.5%); family doctor/general practitioner (9.3%); MoH (3.7%); non-medical sources (16.8%); internet sources (7.8%); family and friends (6.1%); and hajj travel (2.9%) |

| Migault C 2019 [39] | France | Cross-sectional study | Hajj pilgrims | Pre-hajj education health program about Middle East respiratory syndrome | 82 | In-person |

| Beskind LD 2017 [40] | USA | Pre-post interventional | Lay bystanders attending the basketball games | UBV | 96 (Pre-intervention: 45, Post intervention: 51) | Video education |

| Barasheed O 2013 [41] | Saudi Arabia (Australians) | Cross-sectional survey | Hajj pilgrims | Pre-Hajj advice for vaccination | 995 (2011: 442, 2012: 553) | In person (Tour groups) |

| Turkestani A 2013 [42] | Saudi Arabia | Pre-post intervention | Hajj pilgrims | Health education | 300 | In person (health educators) |

| Alamri FA et al., 2018 [43] | Saudi Arabia | Post-intervention | Hajj pilgrims | Health education | 4925 | In-person (medical staff including 163 doctors and 1463 technicians) |

| Author, Year | Contents of Health Education | Type of Outcomes | Effectiveness Outcomes | Implications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ramli R, 2022 [27] | General advice (to bring the medications, check expiry, diet control, and exercise) | Knowledge | There was little/no individualized asthma education | Doctor-participant relation is very important; optimal management assessment by physician; provision of printed or electronic educational resources | Lack of organized education for pilgrims |

| Alqahtani AS 2016 [28] | NR | Experience and practice | Positive experience with the advice (53.6%), negative experience (19%). Increased vaccination among those who had advice from GP (OR:1.9); group leader (OR:2.1) | Awareness, especially to elderly adults and those with pre-existing illness, would be highly beneficial | NR |

| Khamis NK [28] | NR | Practice | Pilgrims who received health education before hajj conducted lower risky behaviors and increased vaccination (87.5% vs. 66.7%), use of protective face mask (24% vs. 3.5%), and hand hygiene (58.7% vs. 11.8%) compared to others | Intensified health education campaigns should be conducted for all pilgrims in their mother countries and Saudi Arabia. This education should contain information on hajj-related health behaviors and how to avoid the conduct of poor behaviors. | Only a lower proportion of participants received the health education |

| Tobaiqy M 2020 [30] | NR | Practice | The use of face mask (p = 0.04), avoiding sun exposure (p = 0.03), and healthy practice score (p = 0.02) was significantly higher among those who had any form of health education compared to those who did not | Health education lectures are the most adapted strategy The content and type of information to include targeting the pilgrim’s language, literacy, and economic aspects. Future studies should focus on the development of accessible health education content in a form that engages pilgrims from diverse backgrounds to promote comprehensive preventative measures during mass religious gatherings and pilgrimages | NR |

| Yezli S 2021 [31] | General advice (Medication Handling and Storage) | Knowledge and practice | Receiving health education on mediation storage was independently associated with good knowledge (OR: 2.7; 95% CI: 1.4–5.0; p = 0.001) 4.7% reported not storing medications properly, and 7.6% would use medications that they know were stored inappropriately | Health education should start at the country of origin and continue during pilgrims’ stay in KSA, and should be led by physicians and pharmacists Beneficial to identify pilgrims with limited health literacy and offer them tailored medication counseling that fits their needs | No information on type and number of medications, self-reported outcome |

| Salmuna ZN 2019 [32] | One-to-one demonstration on how to use handrub provided as well as pamphlets on handrub usage, precautionary measures such as dietary habits, the correct way to use facemask and handrub | Knowledge, practice, and perception | There is no significant difference between pre- and post-hajj knowledge (p = 0.889), practice (p = 0.868), and hand-rub compliance (0.369) among hajj pilgrims in the intervention group. There is a significant (p < 0.013) different between pre- and post-hajj perception among hajj pilgrims in intervention group. | Understanding the perception would assist in pinpointing the knowledge gaps which may be utilized in developing educational programs in order to increase the awareness of the hajj pilgrims. Tailor the health education based on the age and level of education. Educational book with pictures rather than wordy components. | Inadequate awareness |

| Goni MD 2023 [33] | Hajj health educational module provided in pre-during-and post-hajj, followed by formative assessments on prevention of influenza-like illness developed in collaboration with private hajj companies | Practice | Health education significantly reduced the occurrence of RTI symptoms (9.6% vs. 26.0%; p = 0.038); and increased the compliance such as use of face mask (25% vs. 2%; <0.001); N95 mask (21.2% vs. 2%; p = 0.005); disposing the masks (44.2% vs. 16%; p = 0.004); mask use in masjid (44.2% vs. 22%; p = 0.05); and mask use in crowded areas (32.7% vs. 14%; 0.026). | The inclusion of preventive measures in health education is very important | Short period of enrollment and outcome assessment; Control group exposure to other sources of information; Use of self-reported outcomes |

| Mushi A 2021 [34] | Health promotion and training on how and where to seek medical information, health risks during hajj, and health messages on different practices | Practice | Decreased the risky practices | Health authorities in the countries of origin are encouraged to provide health education for pilgrims prior to arrival in KSA for Hajj. | Fewer participants enrollment |

| Yezli S 2021 (2) [35] | Education on insulin storage | Knowledge | Previous health education significantly improved their knowledge score on appropriate insulin storage (0.52 ± 0.21 vs. 0.38 ± 0.19; p = 0.001) | Health education for diabetic patients should start at the country of origin and continue during the Hajj pilgrimage, led by physicians and pharmacists, and the pilgrims’ medical missions | A smaller sample size, the Sampling methodology, and the potential for volunteer bias |

| Goni MD 2021 [36] | Smartphone-based module on knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding respiratory tract infection prevention | Knowledge, attitude, practice | There was no significant improvement in knowledge (17.46 vs. 16.15; p = 0.169), attitude (33.36 vs. 31.96; p = 0.101), and practice (28.10 vs. 26.58; p = 0.078) between intervention and control groups. | Mobile phone technology to gather information on infections associated with mass gathering and travelers makes compliance with prevention practices achievable. | Intrinsic deficiencies and hindrances in implementation. |

| Mahdi H 2020 [37] | General advice | Knowledge | No significant difference in practice based on the knowledge level | Foreign pilgrims are generally better informed and better prepared for Hajj travel since health authorities in their countries of origin are mandated to ensure health advice to pilgrims on communicable diseases Giving advice by Islamic scholars about the importance of alcohol-based hand rubs and reinforcing how this practice does not harm pilgrims could potentially eliminate taboos surrounding the use of alcohol-based hygienic products and, in turn, enhance compliance | Domestic pilgrims who did not have any travelling |

| Alqahtani AS 2019 [38] | General advice | Practice | Those who had chronic conditions were more likely to seek advice from medical sources than those who did not have any chronic conditions (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 2.6, 95% CI: 1.1–6.4, p = 0.03) | NR | Lack of causal inference, recall bias due to self-reported survey |

| Migault C 2019 [39] | Information about MERS-CoV provided by a nurse, using an information leaflet | Knowledge | Delivery of educational information increased the overall rate of correct responses (11 of 13) about MERS-CoV. However, the individual response to specific domains such as routes of transmission, symptoms, preventive behaviors to adopt, vaccines, and specific treatments remained lower than 50% | Information targeting the public is the preferred means to implement infection control | Though the level of knowledge is improved, not effective in controlling the epidemic |

| Beskind LD 2017 [40] | 30 s UBV was shown on screen in the middle of the gymnasium (Jumbotron) that illustrated a step-by-step demonstration on how to perform CCO-CPR using the three C’s (Check, Call 911, Compress). | Practice | No significant difference between groups for the proportion of participants’ responsiveness (Call to 911/AED, started compressions within 2 min) and chest compression rate. Significant improvement found in chest compression depth hands-off time following the video intervention. | Mass media interventions to improve the performance of bystander CPR have grown and become a common method for public awareness campaigns | Study conducted in a simulated situation that may not be applicable to how participants would perform under the stress of a true emergent scenario, selection bias due to convenient sampling |

| Barasheed O 2013 [41] | NR | Practice | 89% Australian pilgrims received influenza vaccine in 2012 due to tour group leaders’ recommendation, awareness about the availability of influenza vaccine, and an increased perception of risk | Recommendations of religious leaders like Imams and tour group leaders were important in enhancing the uptake of influenza vaccine among pilgrims (Enhancing the prevention strategies to RTIs). | Level of education and occupation could influence pilgrims’ perception about influenza vaccine, but these data were not collected |

| Turkestani A 2013 [42] | Provided effective health education to pilgrims in their mother tongue at their dormitories in the holy places through the pictorial chart as well as the distribution of pictorial pamphlets | Knowledge | Health education significantly increased the rate of correct answers (p < 0.05) 99.6% agreed the HEA program aboard the buses was beneficial | HEA program should continue during hajj season Research should be focused on understanding the impact of health education on any change in health Methods to provide standardized, pre-departure health education to pilgrims should be explored. Health education materials should be prepared in concert with the Ministry of Health and shared through working with air carriers and charter companies serving Hajj ports of entry to provide in-flight health education videos | NR |

| Alamri FA et al., 2018 [43] | Health education | Practice | All (99.6%) participants benefited from health education. The Mean and standard deviation of practice score were 6.7 ± 2.1 out of 8. Practice score in general was good. 99.9% of participants used masks in crowded places | Public awareness through social media should be used for education; gender is not a factor that affects health education | Older population had a high chance of comorbidities and health issues |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zaini, R.; Abdulkhaliq, A.A.; Saleh, S.A.K.; Adly, H.M.; Aldahlawi, S.A.; Alharbi, L.A.; Almoallim, H.M.; Hariri, N.H.; Alghamdi, I.A.; Obaid, M.S.; et al. Health Education in Mass Gatherings: A Scoping Review to Guide Public Health Preparedness and Practice. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1926. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151926

Zaini R, Abdulkhaliq AA, Saleh SAK, Adly HM, Aldahlawi SA, Alharbi LA, Almoallim HM, Hariri NH, Alghamdi IA, Obaid MS, et al. Health Education in Mass Gatherings: A Scoping Review to Guide Public Health Preparedness and Practice. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1926. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151926

Chicago/Turabian StyleZaini, Rania, Altaf A. Abdulkhaliq, Saleh A. K. Saleh, Heba M. Adly, Salwa Abdulmajeed Aldahlawi, Laila A. Alharbi, Hani M. Almoallim, Nahla H. Hariri, Ismail Ahmad Alghamdi, Majed Sameer Obaid, and et al. 2025. "Health Education in Mass Gatherings: A Scoping Review to Guide Public Health Preparedness and Practice" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1926. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151926

APA StyleZaini, R., Abdulkhaliq, A. A., Saleh, S. A. K., Adly, H. M., Aldahlawi, S. A., Alharbi, L. A., Almoallim, H. M., Hariri, N. H., Alghamdi, I. A., Obaid, M. S., Alkhotani, A. M. A., Alhazmi, A. S. H., Khan, A. A., Alamri, F. A., & Garout, M. A. (2025). Health Education in Mass Gatherings: A Scoping Review to Guide Public Health Preparedness and Practice. Healthcare, 13(15), 1926. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151926