Self-Management Interventions for Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Methods

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3.1. Participants

2.3.2. Intervention

2.3.3. Comparisons

2.3.4. Outcomes

2.3.5. Study Design

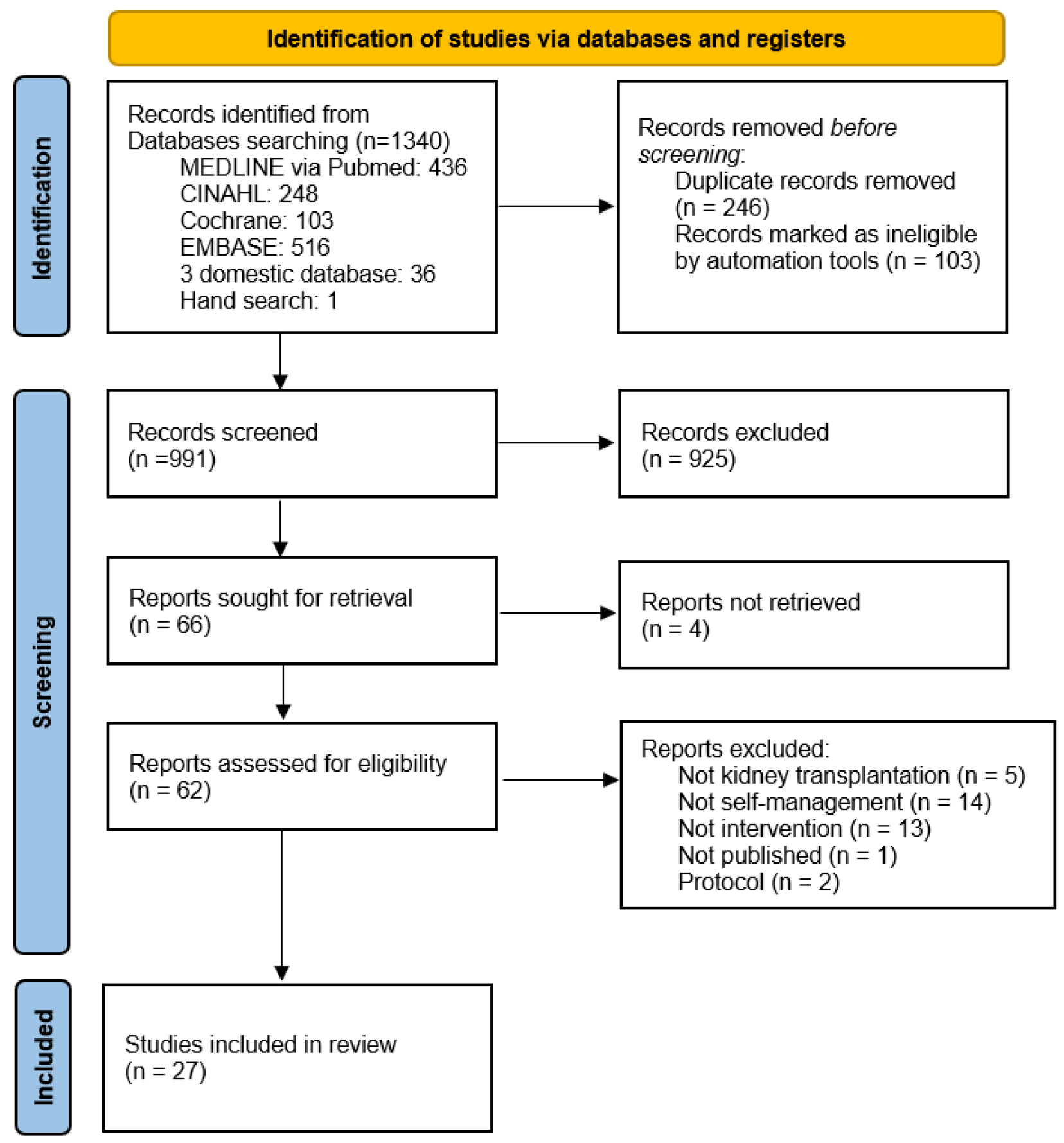

2.4. Search Outcome

2.5. Quality Appraisal

2.6. Data Abstraction

2.7. Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Selected Literature

3.2. Methodological Quality Assessment of Literature

3.3. Self-Management Interventions for Kidney Transplant Recipients

3.4. Outcomes of Self-Management Interventions Applied to Kidney Transplant Recipients

4. Discussion

4.1. Types of Self-Management Interventions for Kidney Transplant Patients: Educational Interventions and Mobile Apps

4.2. Self-Management Intervention Methods for Kidney Transplant Patients

4.3. Self-Management Intervention Effects for Kidney Transplant Patients

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Network for Organ Sharing. Current State of Organ Donation and Transplantation: Transplant Trends. United Network for Organ Sharing. Available online: https://unos.org/data/ (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- National Institute of Organ Tissue Blood Management. Statistical Data. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Updated 2023. Available online: https://www.konos.go.kr/board/boardViewPage.do (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Mayo Clinic Staff. Kidney Transplant; Mayo Clinic Publications: Rochester, MN, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/kidney-transplant/about/pac-20384777 (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Gordon, E.J.; Prohaska, T.; Siminoff, L.A.; Minich, P.J.; Sehgal, A.R. Can focusing on self-care reduce disparities in kidney transplantation outcomes? Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2005, 45, 935–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdem, C.; Cebeci, F. Reliability and validity of the Turkish version of the self-management scale for kidney transplant recipients. Rev. Nefrol. Dial. Traspl. 2022, 42, 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Sim, M.K.; Son, S.Y.; Ju, M.K. Factors influencing the self-management of kidney transplant patients based on self-determination theory: A cross-sectional study. Korean J. Transplant. 2022, 36, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dew, M.A.; DiMartini, A.F.; Dabbs, A.D.V.; Myaskovsky, L.; Steel, J.; Unruh, M.; Switzer, G.E.; Zomak, R.; Kormos, R.L.; Greenhouse, J.B. Rates and risk factors for nonadherence to the medical regimen after adult solid organ transplantation. Transplantation 2007, 83, 858–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, E.J.; Gallant, M.; Sehgal, A.R.; Conti, D.; Siminoff, L.A. Medication-taking among adult renal transplant recipients: Barriers and strategies. Transpl. Int. 2009, 22, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganjali, R.; Sabbagh, M.G.; Nazemiyan, F.; Mamdouhi, F.; Aval, S.B.; Taherzadeh, Z.; Nabavi, F.H.; Golmakani, R.; Tohidinezhad, F.; Eslami, S. Factors associated with adherence to immunosuppressive therapy and barriers in Asian kidney transplant recipients. ImmunoTargets Ther. 2019, 8, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Han, D.J.; Kim, K.S.; Chu, S.H. Medication adherence in patients taking immunosuppressants after kidney transplantation. Korean J. Transplant. 2010, 24, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsky, B.W.; Takemoto, S.K.; Lentine, K.L.; Burroughs, T.E.; Schnitzler, M.A.; Salvalaggio, P.R. Transplant outcomes and economic costs associated with patient noncompliance to immunosuppression. Am. J. Transplant. 2009, 9, 2597–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taj, S.M.; Baghaffar, H.; Alnajjar, D.K.; Almashabi, N.K.; Ismail, S. Prevalence of non-adherence to immunosuppressive medications in kidney transplant recipients: Barriers and predictors. Ann. Transplant. 2021, 26, e928356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheith, O.A.; El-Saadany, S.A.; Abuo Donia, S.A.; Salem, Y.M. Compliance with recommended lifestyle behaviors in kidney transplant recipients: Does it matter in living donor kidney transplant? Iran J. Kidney Dis. 2008, 2, 218–226. [Google Scholar]

- Kluch, M.; Kurnatowska, I.; Matera, K.; Łokieć, K.; Puzio, T.; Czkwianianc, E.; Grzelak, P. Nutrition trends in patients over the long term after kidney transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2020, 52, 2357–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobus, G.; Małyszko, J.; Małyszko, J.S.; Puza, E.; Bachórzewska-Gajewska, H.; Myśliwiec, M. Compliance with lifestyle recommendations in kidney allograft recipients. Transplant. Proc. 2011, 43, 2930–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, E.; Rasmussen, K.; Jemec, G.B. Patients’ knowledge of the risk of skin cancer following kidney transplantation. Ugeskr. Laeger. 2009, 171, 3341–3345. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kenawy, A.S.; Gheith, O.; Al-Otaibi, T.; Othman, N.; Atya, H.A.; Al-Otaibi, M.; Nagy, M.S. Medication compliance and lifestyle adherence in renal transplant recipients in Kuwait. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2019, 13, 1477–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamieson, N.J.; Hanson, C.S.; Josephson, M.A.; Gordon, E.J.; Craig, J.C.; Halleck, F.; Budde, K.; Tong, A. Motivations, challenges, and attitudes to self-management in kidney transplant recipients: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 67, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B.; Radek, M.; Ciałkowska-Rysz, A.; Gluba-Brzózka, A. Diabetes and cardiovascular risk in renal transplant patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Xiong, R.; Hu, Q.; Li, Q. Effects of nursing intervention based on health belief model on self-perceived burden, drug compliance, and quality of life of renal transplant recipients. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2022, 2022, 3001780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangto, P.; Srisuk, O.; Chunpeak, K.; Hutchinson, A.; van Gulik, N. Effectiveness of a multidisciplinary self-management education programme for kidney transplant recipients in Thailand. J. Kidney Care 2022, 7, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, L.; Lushin, E.N.; Hofmeyer, B.; Ensor, C.; Wilson, N.; Tremblay, S.; Campara, M.; American Society of Transplantation Transplant Pharmacy Community of Practice. Discharge medication procurement and education after kidney transplantation. Clin. Transplant. 2019, 33, e13627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, S.; Khoshrounejad, F.; Golmakani, R.; Taherzadeh, Z.; Tohidinezhad, F.; Mostafavi, S.M.; Ganjali, R. Effectiveness of IT-based interventions on self-management in adult kidney transplant recipients: A systematic review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Joo, M.; Chang, M.; Kim, Y. Establishment of a national database for post-transplant management of organ transplant patients. J. Korean Soc. Transplant. 2007, 21, 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Calella, P.; Hernández-Sánchez, S.; Garofalo, C.; Ruiz, J.R.; Carrero, J.J.; Bellizzi, V. Exercise training in kidney transplant recipients: A systematic review. J Nephrol. 2019, 32, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, A.; Clarke, M.; Dooley, G.; Ghersi, D.; Moher, D.; Petticrew, M.; Stewart, L. The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: An international prospective register of systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2012, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidwell, S.; Jensen, M.F. Using a search protocol to identify sources of information: The COSI model. In Etext on Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Information Resources [Internet]; United States National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, Health & Human Services: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2003; Volume 6, p. 14. Available online: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/archive/20060905/nichsr/ehta/chapter3.html#COSI (accessed on 5 July 2016).

- JBI. Critical Appraisal Tools; 2020a. Available online: https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2021-10/Checklist_for_RCTs.docx (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- JBI. Critical Appraisal Tools; 2020b. Available online: https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2021-10/Checklist_for_Quasi-Experimental_Appraisal_Tool%20%281%29.docx (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Park, S.; Lee, T. Factors influencing Korean nurses’ intention to stay: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2018, 24, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghakhani, N.; Maslakpak, M.H.; Jalali, S.; Parizad, N. Self-care education program as a new pathway toward improving quality of life in kidney transplant patients: A single-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Exp. Clin. Transplant. 2021, 19, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchfeld, D.C.; Vagi, R.-K.; Lüdtke, K.; Schieffer, E.; Güler, F.; Einecke, G.; Jäger, B.; de Zwaan, M.; Nöhre, M. Cognitive-behavioral and dietary weight loss intervention in adult kidney transplant recipients with overweight and obesity: Results of a pilot RCT study (Adi-KTx). Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1071705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Been-Dahmen, J.M.J.; Beck, D.K.; Peeters, M.A.C.; van der Stege, H.; Tielen, M.; van Buren, M.C.; Ista, E.; van Staa, A.; Massey, E.K. Evaluating the feasibility of a nurse-led self-management support intervention for kidney transplant recipients: A pilot study. BMC Nephrol. 2019, 20, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambord, J.; Couzi, L.; Merville, P.; Moreau, K.; Xuereb, F.; Djabarouti, S. Benefit of a pharmacist-led intervention for medication management of renal transplant patients: A controlled before-and-after study. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2021, 12, 20406223211005275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, J.; Fortin, M.-C.; Auger, P.; Rouleau, G.; Dubois, S.; Boudreau, N.; Vaillant, I.; Gélinas-Lemay, É. Web-based tailored intervention to support optimal medication adherence among kidney transplant recipients: Pilot parallel-group randomized controlled trial. JMIR Form. Res. 2018, 2, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enrico, M.; Klika, R.; Ingletto, C.; Mascherini, G.; Pedrizzetti, G.; Stefani, L. Changes in global longitudinal strain in renal transplant recipients following 12 months of exercise. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2018, 13, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoseinian, M.; Mohebi, M.; Sadat, Z.; Ajorpaz, N.M. Effect of educating health promotion strategies model on self-care self-efficacy in elderly with kidney transplantation. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2023, 12, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, C.Y.; Lin, L.W.; Su, Y.W.; Yeh, S.H.; Lee, L.N.; Tsai, F.M. The effects of an empowerment intervention on renal transplant recipients: A randomized controlled trial. J. Nurs. Res. 2016, 24, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabeen, R.; Perveen, K.; Afzal, M.; Khan, S. Effect of nurse-led self-management support intervention on quality of life among kidney transplant patients. Med. Forum Mon. 2021, 32, 165–169. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, H.W.; Song, C.E.; An, M. Feasibility and preliminary effects of a theory-based self-management program for kidney transplant recipients: A pilot study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; You, H.S. The effects of an empowerment education program for kidney transplantation patients. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2017, 47, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwaiti, S.; Ghadami, A.; Yousefi, H. Effects of the self-management program on the quality of life among kidney-transplant patients in Isfahan’s Hazrat Abolfazl Health and Medical Charity in 2015. Ann. Trop. Med. Public Health 2017, 10, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGillicuddy, J.W.; Gregoski, M.J.; Weiland, A.K.; A Rock, R.; Brunner-Jackson, B.M.; Patel, S.K.; Thomas, B.S.; Taber, D.J.; Chavin, K.D.; Baliga, P.K.; et al. Mobile health medication adherence and blood pressure control in renal transplant recipients: A proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2013, 2, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollazadeh, F.; Hemmati Maslakpak, M.H. The effect of teach-back training on self-management in kidney transplant recipients: A clinical trial. Int. J. Community Based Nurs. Midwifery 2018, 6, 146–155. [Google Scholar]

- O’bRien, T.; Russell, C.L.; Tan, A.; Mion, L.; Rose, K.; Focht, B.; Daloul, R.; Hathaway, D. A pilot randomized controlled trial using SystemCHANGE™ approach to increase physical activity in older kidney transplant recipients. Prog. Transplant. 2020, 30, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’bRien, T.; Rose, K.; Focht, B.; Al Kahlout, N.; Jensen, T.; Heareth, K.; Nori, U.; Daloul, R. The feasibility of Technology, Application, Self-Management for Kidney (TASK) intervention in post-kidney transplant recipients using a pre/posttest design. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2024, 10, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, N.; Al-Otaibi, T.; Halim, M.A.; Said, T.; Elserwy, N.; Mahmoud, F.; Abduo, H.; Jahromi, M.; Nampoory, N.; Gheith, O.A. Effect of repeated structured diabetes education on lifestyle knowledge and self-care diabetes management in kidney transplant patients with posttransplant diabetes. Exp. Clin. Transplant. 2024, 22 (Suppl. S1), 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, M.D.P.; Stauffer, N.M.; Lee, H.-J.; Chow, S.-C.; Satoru, I.B.; Moats, L.R.; Swan-Nesbit, S.R.; Li, Y.; Roberts, J.K.; Ellis, M.J.; et al. MyKidneyCoach, Patient Activation, and Clinical Outcomes in Diverse Kidney Transplant Recipients: A randomized control pilot trial. Transplant. Direct 2023, 9, e1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, J.K.; Friedewald, J.J.; Desai, A.; Gordon, E.J. Response across the health-literacy spectrum of kidney transplant recipients to a sun-protection education program delivered on tablet computers: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Cancer 2015, 1, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid-Mohler, G.; Zala, P.; Graf, N.; Witschi, P.; Mueller, T.F.; Wüthrich, R.P.; Huber, L.; Fehr, T.; Spirig, R. Comparison of a behavioral versus an educational weight management intervention after renal transplantation: A randomized controlled trial. Transplant. Direct 2019, 5, e507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, M.K.; Son, S.Y. The effects of an individual educational program on self-care knowledge and self-care behavior in kidney transplantation patients. J. East-West Nurs. Res. 2012, 18, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Soltannezhad, F.; Farsi, Z.; Jabari Moroei, M. The effect of educating health promotion strategies on self-care self-efficacy in patients undergoing kidney transplantation: A double-blind randomized trial. Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 2013, 2, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Jin, Q.; Zhu, L.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, W. Application of rapid rehabilitation surgical nursing combined with continuous nursing in self-care ability, medication compliance and quality of life of renal transplant patients. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 844533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesołowska-Górniak, K.; Wójtowicz, M.; Federowicz, M.; Gierus, J.; Czarkowska-Pączek, B. The level of daily physical activity and methods to increase it in patients after liver or kidney transplantation. Adv. Rehabil. 2022, 36, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Wang, X.; Li, A.; Yan, Y.; Lu, T.; Wu, Y.; Lin, Z. A study of the effectiveness of mobile health application in a self-management intervention for kidney transplant patients. Iran J. Kidney Dis. 2023, 17, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khezerloo, S.; Mahmoudi, H.; Sharif Nia, H.; Vafadar, Z. Predictors of self-management among kidney transplant recipients. Urol J. 2019, 16, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Wei, C.; Li, J.; Guo, X.; Gao, F.; Zhao, P.; Liu, H. Development and validation of the Chinese version of the self-management support scale for kidney transplant recipients. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khezerloo, S.; Mahmoudi, H.; Vafadar, Z.; Sharifnia, H. Self-management behaviors in kidney transplant recipients: Qualitative content analysis. Nurs. Midwifery J. 2023, 21, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urstad, K.H.; Andersen, M.H.; Øyen, O.; Moum, T.; Wahl, A.K. Patients’ level of knowledge measured five days after kidney transplantation. Clin. Transplant. 2011, 25, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavaldà, J.; Vidal, E.; Lumbreras, C. Infection prevention in solid organ transplantation. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2012, 30 (Suppl. S2), 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.; Rosaasen, N.; Taylor, J.; Mainra, R.; Shoker, A.; Blackburn, D.; Wilson, J.; Mansell, H. Health literacy, knowledge, and patient satisfaction before kidney transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2016, 48, 2608–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosaasen, N.; Taylor, J.; Blackburn, D.; Mainra, R.; Shoker, A.; Mansell, H. Development and validation of the kidney transplant understanding tool (K-TUT). Transplant. Direct 2017, 3, e132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, R.H.; Elsworth, G.R.; Whitfield, K. The health education impact questionnaire (heiQ): An outcomes and evaluation measure for patient education and self-management interventions for people with chronic conditions. Patient Educ. Couns. 2007, 66, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Zhao, F.; Nianogo, R.A. Interventions in hypertension: Systematic review and meta-analysis of natural and quasi-experiments. Clin. Hypertens. 2022, 28, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hooft, S.M.; Been-Dahmen, J.M.J.; Ista, E.; van Staa, A.; Boeije, H.R. A realist review: What do nurse-led self-management interventions achieve for outpatients with a chronic condition? J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 1255–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study First Author (Year, Country) | Research Design | Patient Sample Size (n) | Patients’ Age (Mean /Median) | Intervention | Control | Outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | C | I | C | |||||

| Aghakhani et al. (2021, Iran) [32] | RCT | 29 | 30 | 42.7 | 41.5 | Self-care education program | Routine care | (1) Quality of life |

| Barchfeld et al. (2023, Germany) [33] | RCT | 28 | 28 | 48.2 | 47.7 | Cognitive–behavioral intervention (nutritional counseling) | Brief self-guided intervention | (1) Percentage of weight loss (2) BMI (3) Renal function parameters (4) Quality of life (5) Levels of depression and anxiety |

| Been-Dahmen et al. (2019, Netherlands) [34] | Mixed-method design | 24 | 33 | 59.7 | 59.8 | Nurse-led self-management intervention | Routine care | (1) Self-management knowledge and behavior (2) Quality of life (3) Self-efficacy (4) Feelings after kidney transplantation (5) Quality of nurse-led care (6) Social support (7) NPs’ fidelity to intervention protocol (8) Importance vs. actual attention to topic during nurse-led consultation session |

| Chambord et al. (2021, France) [35] | Before and after comparative study | 44 | 48 | 59.5 | 55.0 | Pharmacist-led interventions | Routine care | (1) Treatment knowledge (2) Medication adherence (3) Measurement of drug exposure |

| Côté et al. (2018, Canada) [36] | RCT | 23 | 16 | 54.0 | 51.4 | Web-based tailored education | Conventional transplantation-related websites | (1) Medication adherence (2) Self-efficacy (3) Medication intake-related skills (4) Medication side effects (5) Self-perceived general state of health |

| Enrico et al. (2018, Italy) [37] | Before and after comparative study | 30 | - | 38.6 | - | Supervised exercise program | N/A | (1) Myocardial function (2) Functional assessment |

| Hoseinian et al. (2023, Iran) [38] | Quasi-experimental study | 30 | 30 | 63.6 | 63.4 | Education based on the model of individual health promotion strategies | Routine care | (1) Self-care self-efficacy - Stress reduction - Adaptation - Decision making - Enjoying life |

| Hsiao et al. (2016, China) [39] | RCT | 56 | 66 | 48.6 | 45.9 | Empowerment support program | Routine care | (1) Perceived level of empowerment (2) Self-care behavior |

| Hu et al. (2022, China) [20] | RCT | 30 | 30 | 45.96 | 45.91 | Nursing intervention based on health belief model | Routine care | (1) Satisfaction (2) Self-perceived burden (2) Drug compliance (3) Anxiety (4) Depression (5) Self-management ability (6) Quality of life |

| Jabeen et al. (2021, Pakistan) [40] | Quasi experimental study (Before and after) | 36 | - | 31.4 | - | Nurse-led self-management program | N/A | (1) Quality of life |

| Jeong et al. (2021, South Korea) [41] | Before and after comparative study | 30 | - | 49.1 | - | Theory-based self-management program | N/A | (1) Autonomy support (2) Competence (3) Self-care agency |

| Kim et al. (2017, South Korea) [42] | Quasi-experimental study (Nonequivalent control group pre-posttest design) | 25 | 28 | 45.48 | 46.43 | Empowerment education program | None | (1) Uncertainty (2) Self-care agency (3) Compliance |

| Kuwaiti et al. (2018, Iran) [43] | RCT | 33 | 34 | 46.3 | 43.2 | Chronic disease self-management training program | Attending one training session on diet | (1) Quality of life |

| McGillicuddy et al. (2013, USA) [44] | RCT | 9 | 10 | 42.4 | 57.6 | Mobile phone-based medication monitoring | Education related to post- transplantation medical care | (1) Medication adherence |

| Mollazadeh et al. (2018, Iran) [45] | RCT | 42 | 37 | 41.27 | 38.0 | Teach-back training-based education | Unknown | (1) Self-management |

| O’Brien et al. (2020, USA) [46] | RCT | 25 | 25 | 65.7 | 65.1 | SystemCHANGE + activity tracker intervention | Received transplantation-related educational materials | (1) Daily steps (2) Health outcomes - Blood pressure - Heart rate - Body mass index - Waist circumference - Physical function (6 min walk test) |

| O’Brien et al. (2024, USA) [47] | Before and after comparative study | 20 | - | 59.5 | - | Technology, Application, Self-Management for Kidney (TASK) intervention | N/A | (1) Blood pressure (2) Weight (3) Fruits/vegetable intake, fiber intake, sodium intake (4) Self-efficacy to exercise (5) Perceived stress |

| Othman et al. (2024, Kuwait) [48] | RCT | 140 | 70 | 44.9 | 44.0 | Structured diabetes education | Conventional education | (1) Knowledge - Healthy food knowledge - Exercise knowledge - Healthy foot care (2) Biochemical parameters - HbA1c - Lipid profile - Renal function tests - Fasting sugar - Weight, BMI, and waist circumference (3) Diabetes self-care |

| Pollock et al. (2023, USA) [49] | RCT | 7 | 9 | 41.6 | 35.9 | Self-management app (MyKidneyCoach), tailored text, telephonic clinical nurse coaching | Self-management app (MyKidneyCoach) | (1) Patient activation measure (2) Partners in health (self-management) (3) Nutrition self-efficacy score |

| Robinson et al. (2015, USA) [50] | RCT | 84 | 86 | 51.0 | 49.0 | Educational sun protection program | Received general skin care information | (1) Knowledge of skin cancer and sun protection (2) Attitudes - Recognition of personal risk to skin cancer - Willingness to change sun protection behavior (3) Sun protection behavior - Sun protection - Daily number of hours staying outdoors |

| Schmid-Mohler et al. (2019, Switzerland) [51] | RCT | 61 | 62 | 50.5 | 49.8 | Educational Weight Management Intervention | Routine care with brochure | (1) BMI (2) Body composition (LTM) (3) WHR (4) Physical activity - Self-reported physical activity - Number of steps (5) Perception of care |

| Sim et al. (2012, South Korea) [52] | Quasi-experimental study (Nonequivalent one group pre-posttest design) | 42 | - | 47.4 | - | Individual educational program | N/A | (1) Self-care knowledge (2) Self-care behavior |

| Soltannezhad et al. (2013, Iran) [53] | RCT | 26 | 26 | 38.12 | 37.65 | Educating health promotion strategies | Routine care | (1) Self-care self-efficacy |

| Song et al. (2022, China) [54] | RCT | 30 | 30 | 31.85 | 32.59 | FTS nursing combined with continuous nursing | FTS nursing | (1) Patients’ comfort (2) Self-care ability (3) Medication compliance (4) Quality of life |

| Thangto et al. (2022, Thailand) [21] | Before and after comparative study | 50 | - | 39.0 | - | Multidisciplinary education program | N/A | (1) Knowledge - Self-care knowledge - Nutrition and dietary knowledge - Immunosuppressive drugs knowledge |

| Wesołowska-Górniak et al. (2022, Poland) [55] | RCT | 49 † | 51 † | 33.8 | 36.2 | Self-monitoring of daily physical activity using a pedometer | None | (1) Average daily number of steps within 7 days (2) Physical activity (3) Body composition - BMI - Fat% - FFM |

| Xie et al. (2023, China) [56] | Retrospective study | 80 | 80 | - | - | Mobile medical application self-management behavior intervention | Conventional self-management behavior intervention | (1) Self-management behaviors (2) Quality of life (3) Self-efficacy |

| Design/Citation | Critical Appraisal | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Total | |

| RCTs | ||||||||||||||

| Aghakhani et al. (2021) [32] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 10/13 † |

| Barchfeld et al. (2023) [33] | Y | UC | Y | N | N | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9/13 † |

| Côté et al. (2018) [36] | Y | Y | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 12/13 † |

| Hsiao et al. (2016) [39] | Y | Y | Y | UC | UC | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC | 9/13 † |

| Hu et al. (2022) [20] | Y | UC | Y | UC | UC | UC | Y | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC | 7/13 † |

| Kuwaiti et al. (2018) [43] | Y | UC | Y | UC | UC | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC | 8/13 † |

| McGillicuddy et al. (2013) [44] | Y | UC | Y | UC | UC | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8/13 † |

| Mollazadeh et al. (2018) [45] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC | Y | UC | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10/13 † |

| O’Brien et al. (2020) [46] | Y | Y | Y | UC | UC | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10/13 † |

| Othman et al. (2024) [48] | N | N | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10/13 † |

| Pollock et al. (2023) [49] | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10/13 † |

| Robinson et al. (2015) [50] | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 10/13 † |

| Schmid-Mohler et al. (2019) [51] | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC | 10/13 † |

| Soltannezhad et al. (2013) [53] | Y | UC | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC | 10/13 † |

| Song et al. (2022) [54] | Y | Y | Y | UC | UC | UC | Y | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC | 8/13 † |

| Wesołowska-Górniak et al. (2022) [55] | Y | Y | Y | UC | UC | Y | UC | UC | UC | Y | Y | Y | UC | 7/13 † |

| Quasi-experimental studies | ||||||||||||||

| Chambord et al. (2021) [35] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | 8/9 ‡ |

| Enrico et al. (2018) [37] | Y | N/A | N/A | N | Y | N/A | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | 5/9 ‡ |

| Hoseinian et al. (2023) [38] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | 9/9 ‡ |

| Jabeen et al. (2021) [40] | Y | N/A | N/A | N | Y | N/A | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | 5/9 ‡ |

| Jeong et al. (2021) [41] | Y | N/A | Y | N | Y | N/A | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | 6/9 ‡ |

| Kim et al. (2017) [42] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | 9/9 ‡ |

| O’Brien et al. (2024) [47] | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | 8/9 ‡ |

| Sim et al. (2012) [52] | Y | N/A | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | 7/9 ‡ |

| Thangto et al. (2022) [21] | Y | Y | Y | N | N | UC | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | 6/9 ‡ |

| Xie et al. (2023) [56] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | 8/9 ‡ |

| Mixed-method studies | ||||||||||||||

| Been-Dahmen et al. (2019) [34] | Y | UC | Y | Y | Y | UC | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | 7/9 ‡ |

| Intervention Type | Study First Author (Year) | Providers | Target | Sessions (Duration) | Intervention Contents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Aghakhani et al. (2021) [32] | Nurse | KT patients | 3 sessions of 30 to 45 min (3 weeks) | IG received face-to-face education programs using an educational booklet. The content of the program included the type of disease, medication, diet, and physical and self-care activities. |

| Côté et al. (2018) [36] | Nurse/web | KT patients | 3 sessions, each 20 to 30 min (3 months) | Transplant-TAVIE, a web-based tailored nursing intervention that empowers kidney transplant recipients to manage their immunosuppressive drug treatment. The sessions aimed to help users incorporate the therapeutic regimen into their daily routine, cope with medication side effects, handle situations or circumstances that could interfere with medication intake, interact with healthcare professionals, and mobilize social support. The learning objectives included strengthening various capacities such as self-motivation and self-monitoring (session 1), problem-solving and emotional control (session 2), and social interaction (session 3). | |

| Hoseinian et al. (2023) [38] | Nurse | Patients undergoing KT | 8 sessions (2 months) | - Education in the intervention group was based on the model of health promotion strategies. The intervention method was such that each individual patient was educated using the methods of lecture, discussion, and question and answer. - The patients of the intervention group were educated through health promotion strategies and considering three levels of prevention in the areas of stress reduction, adaptation, decision making, enjoying life, activity, rest, nutrition, and medication. | |

| Hu et al. (2022) [20] | Nurse | KT patients (≥3 months) | 3 sessions (3 months) | One session was conducted each month. (1) Drug-taking manual: the benefits of transplantation, the necessity of taking immunosuppressive drugs, the consequences of taking immunosuppressive drugs, the methods of administration, and matters associated with various immunosuppressive drugs requiring attention regarding (e.g., medication schedule). (2) Methods of blood concentration monitoring and matters requiring attention to keep the blood concentration stable, the consequences of rejection (a small amount), the occurrence and treatment of infection (overdose) after taking immunosuppressive drugs, and behavior feedback results of the first month. (3) Prevention and treatment of complications, including matters requiring attention such as self-protection and modification of lifestyle, as well as the introduction of self-monitoring indicators. | |

| Kim et al. (2017) [42] | Nurse | KT patients | 6 sessions, 60 min per session (6 weeks) | The topics discussed during educational sessions were as follows: (1) program introduction, (2) drug administration, (3) symptoms of rejection and complications, (4) nutritional management, (5) exercising, and (6) management of activities of daily living. The program was delivered through education, listening, conversation, linguistic support, raising issues, and seeking solutions. | |

| Kuwaiti et al. (2018) [43] | Nurse, psychologist, nutritionist | KT patients (≥3 months) | 2.5 hr sessions; 15 hr comprehensive program (6 weeks) | The content of the program included the following: (1) Techniques for addressing problems such as frustration, fatigue, and isolation. (2) Good exercise for maintaining and boosting strength. (3) The efficient use of medications. (4) An effective relationship with family, friends, and healthcare specialists. (5) Nutrition. (6) Process of evaluating new treatments, with emphasis on operational planning, problem-solving, and decision-making. | |

| Mollazadeh et al. (2018) [45] | Nurse | KT patients (3–12 months) | 5 sessions, 60 min per session (3 months) | The contents include self-monitoring and self-care behavior in daily living, early detection and coping with abnormalities after KT, stress management, and management of non-categorized cases. The intervention also consists of an assessment of the patient’s need for self-management education and intensive training that verifies understanding by verbalizing what has been explained. | |

| Othman et al. (2024) [48] | Nurse, public health worker, pharmacist | KT patients (≥6 months) | 6 session, first session: 60 min, other sessions: 30 min (3 months) | The education content was repeated entirely or partly by the researcher according to each patient’s needs. Mixed education techniques, such as description, question, and answer, were used as an education method, and feedback was stimulated to enable patients to understand their self-care management independently. | |

| Robinson et al. (2015) [50] | Audio support education delivered by tablet | KT patients (2–24 months) | 1 session, 23–42 min (waiting time to consult with a nephrologist) | The topics included were as follows: (1) importance of sun protection, (2) skin cancer, (3) risk of developing skin cancer, (4) ways people get sun exposure, (5) choices of sun protection, (6) frequently asked questions about sunscreen, (7) protective clothing, and (8) personalized sun-protection recommendations. | |

| Soltannezhad et al. (2013) [53] | Physician | Patients undergoing KT | 4 sessions, 30 min per session (2 months) | -Educational sessions included topics on stress management, coping strategies, nutrition, exercise, medication adherence, and self-care after surgery, and common complications. -Educational booklet and researcher’s telephone numbers were provided in cases where participants have probable questions. -An educational pamphlet was provided to the family. | |

| Song et al. (2022) [54] | Doctor, nurses, dieticians | Patients undergoing KT | FTS nursing and continuous nursing (6 months) | -The FTS nursing activities were as follows; (1) personalized care plan, (2) preoperative education, (3) intraoperative preparation, (4) postoperative observation, and (5) guidance at discharge. -The continuous nursing activities were as follows; (1) patient follow-up after discharge, (2) gathering of patient’s files, (3) provision of self-management education, (4) personalized adjustment of nursing plan, and (5) provision of psychological care. | |

| Thangto et al. (2022) [21] | Nurse, dietitian, pharmacist | Patients undergoing KT | 3 sessions, 1 h per session (hospitalization) | -The education program consisted of three major sessions covering the three key area of knowledge self-management and care (taught by clinical nurses), nutrition and diet (taught by dietitians), and immunosuppressive drugs (taught by pharmacists). | |

| Education, exercise intervention | Schmid-Mohler et al. (2019) [51] | Nurse | KT patients (≤6 weeks) | 8 or 9 sessions, session 1: 45–60 min sessions 2–3: 45–60 min sessions 4–9: 15–30 min (12 months) | -Educational intervention included as follows: medication self-management, emotional and psycho-social concerns, weight management, physical activity, and recommendations regarding diet and activity. -Behavior intervention was focused on maintenance/achievement of a normal body weight and the integration of physical activity into the daily routine. |

| Exercise intervention | Enrico et al. (2018) [37] | N/A | KT patients (≥12 months) | 3 times a week for 60 min per session (12 months) | The program consisted of aerobic and strength training exercises. An initial goal included achieving 30 min of exercise at least 3 times a week, progressing to 150 min a week of moderate physical exercise by the sixth month, and continuing for the duration of the study. The exercise sessions included strength exercises to enhance the function of eight muscle groups that have been affected in our diseased populations and 15 min of stationary cycling. Diet: The patients were advised to follow a traditional Mediterranean nutritional diet that included consumption of at least two daily portions of fruit and three servings of vegetables, as well as three servings of fish per week and two servings of cereal per week. |

| O’Brien et al. (2020) [46] | Nurse /Mobile phone | KT patients (≥3 months) | Daily usage of SystemCHANGE and activity tracker (6 months) | The personal system-based solutions support and enhance physical activity combined with visual feedback from a mobile activity tracker. SystemCHANGE + activity tracker intervention focuses on guiding individuals to incorporate the desired behavior change as part of their daily or weekly routines. | |

| Wesołowska-Górniak et al. (2022) [55] | Nurse, physician | KT or LT patients (1–5 years) | N/A (3 months) | The patients were required every day to monitor their daily physical activity using a pedometer and to complete a diary of their daily number of steps. | |

| Counselling | Barchfeld et al. (2023) [33] | Physician, clinical psychologist | KT patients (≥3 months) | 12 sessions, each 50 min (6 months) | - Sessions were offered face-to-face or telemedically (via video conferencing or telephone). The intervention included cognitive–behavioral as well as psychoeducational elements. - The content of the intervention included the following: Nutritional and exercise counselling, overweight and obesity, reasons for and against losing weight, eating cues, progress report, resources and behavioral change, mindfulness, vicious circle, stress management, repetition, relapse prevention. |

| Education, counselling | Sim et al. (2012) [52] | Nurse | KT patients (≥ 1 months) | 2 sessions, each 50–60 min (2 weeks) | The topics discussed during educational sessions were as follows: (1) medication and laboratory tests as well as complications and preventive measures, and (2) dietary management, general health management, and exercise. |

| Jeong et al. (2021) [41] | Nurse | Patients who transferred to the ward after KT | 2 sessions, 30 min per session (2 weeks) | Video education included the following content areas: (1) medication, (2) nutrition, (3) exercise, (4) rejection, and (5) complications. Personalized counselling included the following content areas: (1) daily activity, (2) social support, (3) emotional support, (4) self-care motivation, and (5) self-care planning. | |

| Mobile phone-based medication monitoring | McGillicuddy et al. (2013) [44] | Mobile phone | KT patients (≥3 months) | N/A (3 months) | IG received customizable reminder signals (light, chime), phone calls, or text messages at the prescribed dosing day and time. They were contacted by text, email, or phone when alerts indicated medication non-adherence. A weekly summary report was submitted via email, and a summary of each participant’s adherence to medication dosing was provided by a physician. |

| Mobile app | Xie at al. (2023) [56] | Mobile app, nurse | KT patients | N/A | The intervention group used a mobile application to implement self-management behavioral interventions were as follows: (1) Information support: 11 categories of health knowledge related to each stage of Renal Transplantation, (2) Skills guidance: Provide intelligent self-monitoring forms to facilitate patients in recording important data such as daily blood pressure, body weight, and intake and output volume, and provide automatic conversion of water content of each food, intake and output volume statistics, medicine and food, (3) Communication: self-monitoring data and medical side sharing, convenient for nurses and patients at any time to exchange disease changes, seek help, and share disease-related monitoring data. |

| O’Brien et al. (2023) [47] | Mobile app | KT patients | N/A (3 months) | The intervention began with the development of a “Plan” (individual goals for dietary intake and minutes of physical activity), and the participant identified possible ways (personalized solutions based on their everyday routines) to achieve daily goals. For the “Do” component, participants incorporated their personalized solutions into existing routines. The “Study” component enabled the participants to evaluate their dietary and physical activity goal progress with visual feedback (graphs) from the Lose-It© app. The “Act” phase enabled the participants to evaluate the personalized-system solution and determine the achievement of the dietary and physical activity goals. During the session weeks 1–12, the participant completed four steps of the Plan-Do-Study-Act Model with the RA via Zoom. | |

| Mobile app, nursing coaching | Pollock et al. (2023) [49] | Mobile app, nurse | KT patients (≥ 1 months) | N/A (3 months) | The MyKidneyCoach intervention comprised (1) a self-management app that provided educational materials and monitoring of post-transplant care using a smartphone and (2) personalized, text-based, and telephonic coaching from a trained clinical nurse triggered through the app to promote patient activation and self-management after KT. |

| Enhancing motivation intervention | Been-Dahmen et al. (2019) [34] | Nurse/web | KT patients (1–8 months) | 4 sessions (dependent on individual) | In the first session, self-management challenges were assessed using a self-management web-based program, specifically designed for this purpose. Progression toward goal attainment and outcome expectations were discussed in the second and third sessions. Goal progress, relapse prevention, and generalization of learned skills to other challenges were discussed during the fourth session. |

| Enhancing empowerment intervention | Hsiao et al. (2016) [39] | Nurse | KT patients (≤20 years) | Six small-group sessions, each lasting for 120 min (12 weeks) | Topics included setting goals, solving problems, coping with renal transplant, coping with daily stresses, seeking social support, and staying motivated. The sessions consisted of introductions that highlighted the topic, group discussions, and patient identification of problem areas for self-care behaviors after renal transplantation. Furthermore, the emotions associated with these problems were explored, and a set of goals and strategies to overcome these problems was developed. Active learning (sharing experiences with others and choosing personal solutions) was encouraged. |

| Self-management support intervention | Jabeen et al. (2021) [40] | Nurse | KT patients | 3 sessions, 45–60 min per session (4 months) | Three sessions; (1) nurses training, (2) applying the program to patients, and (3) assessment. The content of the program included management of the expected health problems; performance of routine activities; management of emotional changes, such as stress, anxiety, fear, and depression; dietary modifications; management of sleep pattern; and maintenance of effective communication with family and colleagues. |

| Behavioral educational interview intervention | Chambord et al. (2021) [35] | Pharmacist | KT patients (4–12 months) | 30 min, 11 scenarios (4 months) | It was performed at visit 1 in the IG patients, consisted of a behavioral and educational interview. Using the Barrows cards, the patient was provided with a ‘situation’ that represents a problem they might encounter concerning immunosuppressive treatment or pathology. The patient selected one of the three ‘behavior’ cards according to the reaction they would have adopted if placed in this situation. The consequences of the choice were then discussed with the pharmacist leading the interview. |

| Category | Positive Outcomes | Null Outcomes | Mixed Outcomes † |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Outcomes | Treatment knowledge (p < 0.001) [35], self-management knowledge (p < 0.001) [21,48,52], knowledge of skin cancer and sun protection (p = 0.04) [50], perception of care (p < 0.001) [51], quality of life (p < 0.05) [33,40,43,54,56], (p < 0.001) [20,32] | Self-perceived general health status [36], quality of life [34] | Quality of life |

| Behavioral Outcomes | Self-care behavior (p = 0.009) [39], (p < 0.05) [56], (p < 0.001) [40,45], diabetes self-care (p < 0.05) [48], medication adherence (p < 0.05) [20,54], (p < 0.001) [44], self-care ability (p < 0.05) [20,54], self-care self-efficacy (p < 0.001) [38,41,48], (p < 0.05) [56], daily steps (p = 0.03) [46], self-efficacy to exercise (p = 0.003) [47], sun protection behavior (p = 0.01) [50], and treatment compliance (p < 0.001) [42] | Self-care behavior [34], medication adherence [35,36], measurement of drug exposure [35], medication intake-related skills [36], self-care self-efficacy [34,36,53], physical activity [51,55], average daily number of steps within 7 days [55], fruits/vegetable intake, fiber intake, sodium intake [47] | Self-care behavior, medication adherence, self-care self-efficacy, and daily steps |

| Affective Outcomes | Feelings after kidney transplantation, adherence to immunosuppressive medications (p = 0.03) [34], perceived level of empowerment (p = 0.023) [32], satisfaction level (p < 0.05) [20], self-perceived burden (p < 0.05) [20], anxiety/depression (p < 0.05) [20], stress (p = 0.04) [47], autonomy support (p = 0.038) [41], competence (p < 0.001) [41], attitudes (p = 0.02) [50], and uncertainty (p < 0.001) [42] | Feelings after KT, worry about the transplantation/guilt toward the donor/disclosure about the transplantation/responsibility toward others [34], quality of nurse-led care [34], social support [34], and level of patients’ comfort [54], anxiety/depression [33] | Anxiety/depression |

| Health Outcomes | Systolic blood pressure (p = 0.009) [44], diastolic blood pressure (p = 0.00006) [44], HR (p = 0.002) [46], WC (p < 0.001) [46,48], and BMI (p = 0.01) [46], (p < 0.05) [33], weight (p < 0.05) [33], (p = 0.02) [47], HbA1c (p < 0.05) [48], proteinuria (p = 0.016) [48] | Blood pressure [46,47], weight [46], BMI [51,55], body composition LTM [51], 6MWT [46], medication side effects [36], myocardial function [37], renal function parameters [33] | Blood pressure, BMI, and renal function |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, H.; Kang, C.M. Self-Management Interventions for Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1918. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151918

Lee H, Kang CM. Self-Management Interventions for Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1918. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151918

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Hyejin, and Chan Mi Kang. 2025. "Self-Management Interventions for Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1918. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151918

APA StyleLee, H., & Kang, C. M. (2025). Self-Management Interventions for Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 13(15), 1918. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151918