Knowledge and Risk Perception Regarding Keratinocyte Carcinoma in Lay People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- Sample: General population and subsamples thereof. Samples of participants with medical training (e.g., physicians, medical students, or nurses) or skin cancer patients were excluded.

- Phenomenon of Interest: Knowledge about, risk perception, or attitudes towards KC. This also includes awareness, familiarity, or beliefs. Studies focusing only on UV-related knowledge or UV behavioral assessment were excluded.

- Design: Cross-sectional surveys, cohort studies, baseline data of intervention studies.

- Evaluation: Items had to be sufficiently described to ascertain they were distinctly assessing the phenomenon of interest (i.e., no items referring to skin cancer in general or summary scores including other outcomes).

- Research Type: Quantitative, peer-reviewed studies. Qualitative studies, conference abstracts, dissertations, case reports, commentaries, editorials or reviews were excluded.

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Risk of Bias (ROB) Assessment

2.5. Data Synthesis

3. Results

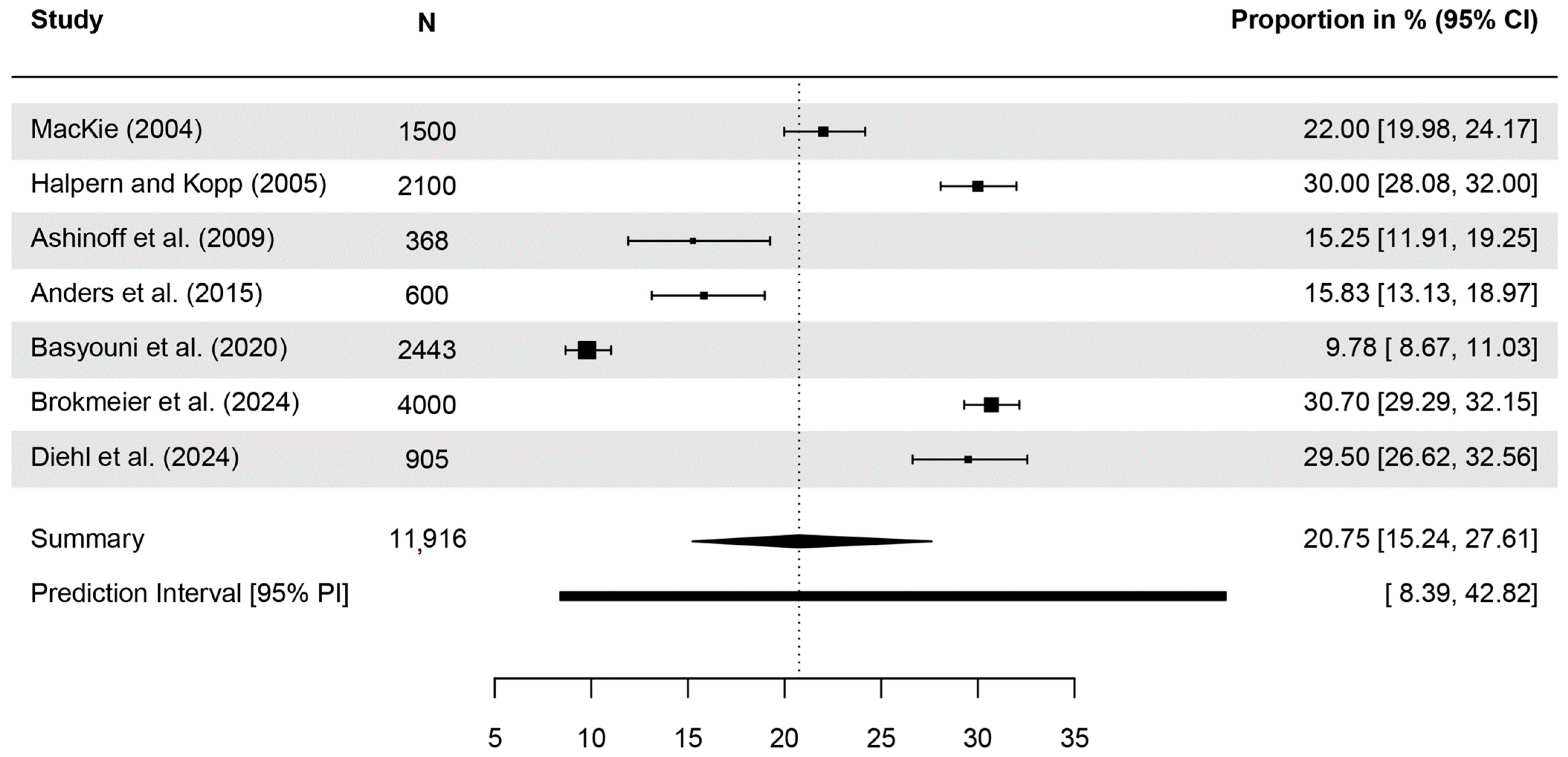

3.1. Awareness of Terms for KC

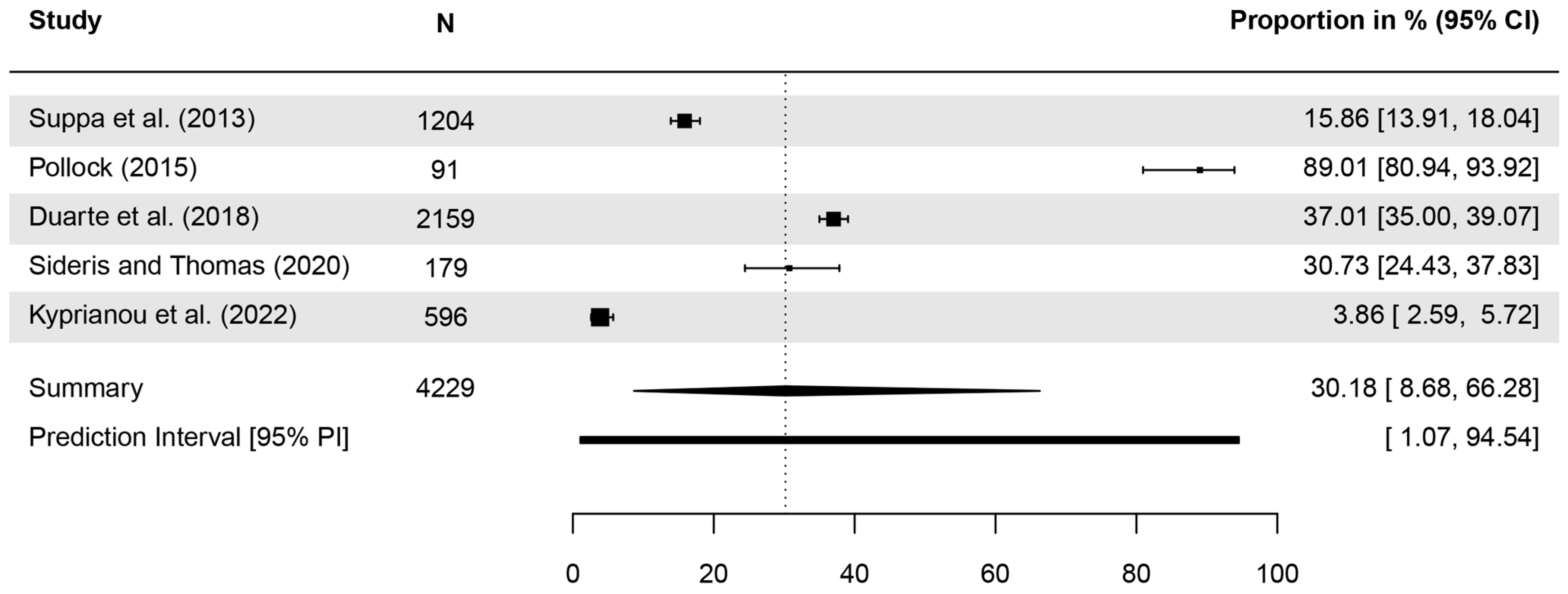

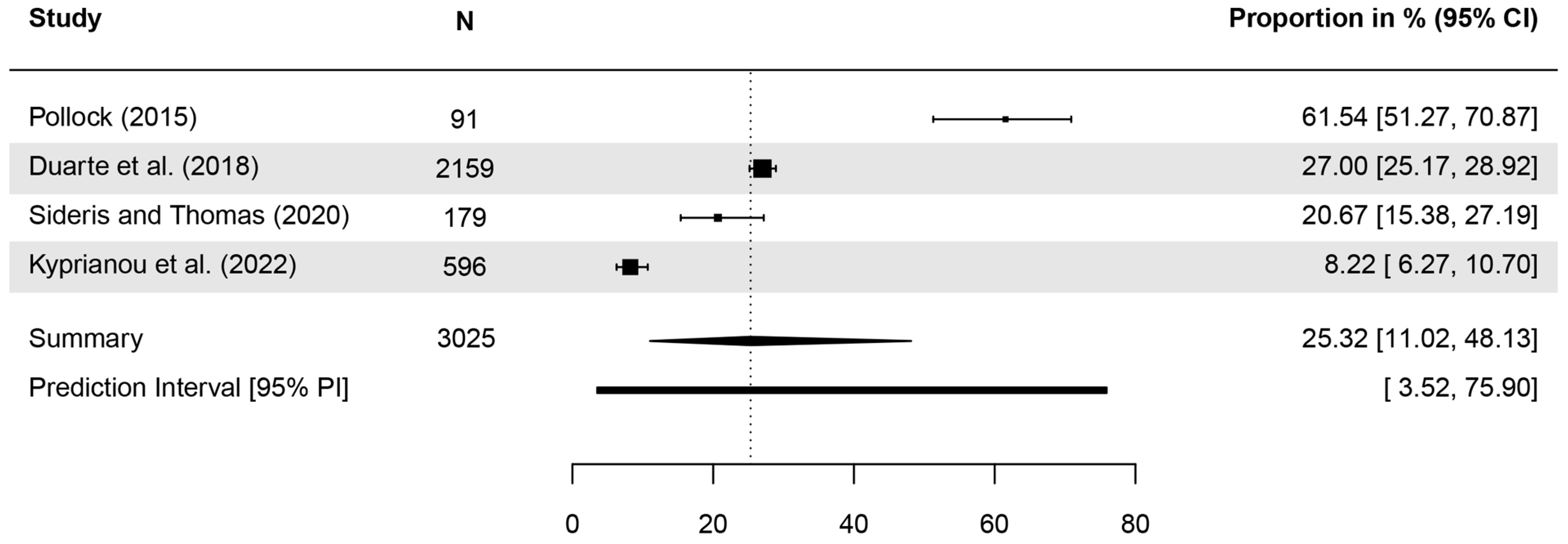

3.2. Identification of KC as a Type of Skin Cancer

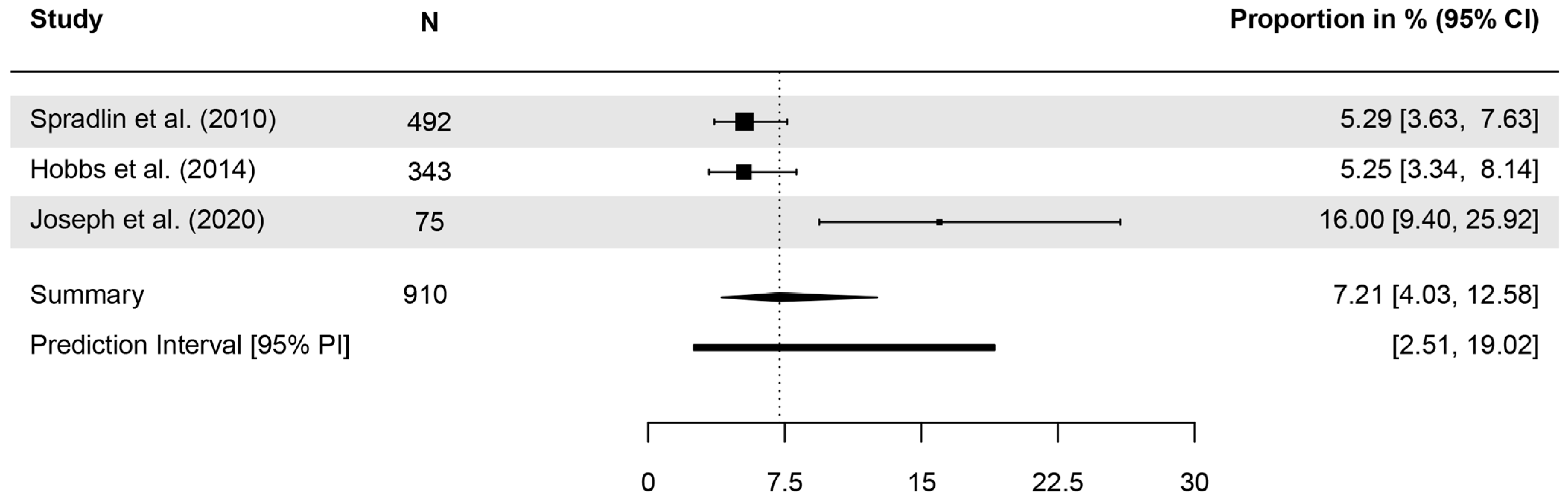

3.3. Knowledge Regarding the Prevalence of KC

3.4. Specific Knowledge Regarding KC

3.5. Concern About Developing KC

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KC | Keratinocyte carcinoma |

| BCC | Basal cell carcinoma |

| SCC | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| ROB | Risk of Bias |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| MM | Malignant melanoma |

| NMSC | Nonmelanoma skin cancer |

| k | Number of studies included in the analyses |

References

- Majid, U.; Wasim, A.; Bakshi, S.; Truong, J. Knowledge, (mis-)conceptions, risk perception, and behavior change during pandemics: A scoping review of 149 studies. Public Underst. Sci. 2020, 29, 777–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.; Harris, P.R.; Epton, T. Does heightening risk appraisals change people’s intentions and behavior? A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 511–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, P.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Sundaram, C.; Harikumar, K.B.; Tharakan, S.T.; Lai, O.S.; Sung, B.; Aggarwal, B.B. Cancer is a preventable disease that requires major lifestyle changes. Pharm. Res. 2008, 25, 2097–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomas, A.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Bath-Hextall, F. A systematic review of worldwide incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012, 166, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, U.; Keim, U.; Garbe, C. Epidemiology of Skin Cancer: Update 2019. In Sunlight, Vitamin D and Skin Cancer; Reichrath, J., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Brochez, L.; Volkmer, B.; Hoorens, I.; Garbe, C.; Röcken, M.; Schüz, J.; Whiteman, D.C.; Autier, P.; Greinert, R.; Boonen, B. Skin cancer in Europe today and challenges for tomorrow. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2025, 39, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimkhani, C.; Boyers, L.N.; Dellavalle, R.P.; Weinstock, M.A. It’s time for “keratinocyte carcinoma” to replace the term “nonmelanoma skin cancer”. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2015, 72, 186–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Laversanne, M.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2024; Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/today (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Verkouteren, J.A.C.; Ramdas, K.H.R.; Wakkee, M.; Nijsten, T. Epidemiology of basal cell carcinoma: Scholarly review. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 177, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, A.C.; Olsen, C.M. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: An epidemiological review. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 177, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, A.C.; Swetter, S.M. Reporting and registering nonmelanoma skin cancers: A compelling public health need. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012, 166, 913–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021); Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation: Seattle, WA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Zhou, L.; Zhong, Y.; Han, L.; Xie, Y.; Wan, M. Global, regional, and national trends in the burden of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer: Insights from the global burden of disease study 1990–2021. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.D.; Borsky, K.; Jani, C.; Crowley, C.; Rodrigues, J.N.; Matin, R.N.; Marshall, D.C.; Salciccioli, J.D.; Shalhoub, J.; Goodall, R. Trends in keratinocyte skin cancer incidence, mortality and burden of disease in 33 countries between 1990 and 2017. Br. J. Dermatol. 2023, 188, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanz, L.; Keim, U.; Katalinic, A.; Meyer, T.; Garbe, C.; Leiter, U. Epidemiology of Keratinocyte Skin Cancer with a Focus on Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2024, 16, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lear, W.; Dahlke, E.; Murray, C.A. Basal cell carcinoma: Review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and associated risk factors. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2007, 11, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.C.; Yen, H.; Heskett, K.M.; Yen, H. The Role of Health Literacy in Skin Cancer Preventative Behavior and Implications for Intervention: A Systematic Review. J. Prev. 2024, 45, 957–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, L.G.; Rowell, D. Health system costs of skin cancer and cost-effectiveness of skin cancer prevention and screening: A systematic review. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 24, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pil, L.; Hoorens, I.; Vossaert, K.; Kruse, V.; Tromme, I.; Speybroeck, N.; Brochez, L.; Annemans, L. Burden of skin cancer in Belgium and cost-effectiveness of primary prevention by reducing ultraviolet exposure. Prev. Med. 2016, 93, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, C.E.; Wheelwright, S.; Harle, A.; Wagland, R. The role of health literacy in cancer care: A mixed studies systematic review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.A.; Haidet, P. Physician overestimation of patient literacy: A potential source of health care disparities. Patient Educ. Couns. 2007, 66, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahar, V.K.; Wilkerson, A.H.; Pearlman, R.L.; Ferris, T.S.; Zardoost, P.; Payson, S.N.; Aman, I.; Quadri, S.S.A.; Brodell, R.T. Skin cancer-related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and practices among the population in Gulf Cooperation Council countries: A systematic search and literature review. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2020, 312, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Ruiz, J.; Montero-Vilchez, T.; Buendia-Eisman, A.; Arias-Santiago, S. Knowledge, Behaviour and Attitudes Related to Sun Exposure in Sportspeople: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziehfreund, S.; Schuster, B.; Zink, A. Primary prevention of keratinocyte carcinoma among outdoor workers, the general population and medical professionals: A systematic review updated for 2019. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 1477–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wohlin, C. Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, London, UK, 13–14 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Grainger, M.J.; Gray, C.T. Citationchaser: A tool for transparent and efficient forward and backward citation chasing in systematic searching. Res. Synth. Methods 2022, 13, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.F.; Nagore, E.; Silva, J.N.M.; Picoto, A.; Pereira, A.C.; Correia, O.J.C. Sun protection behaviour and skin cancer literacy among outdoor runners. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2018, 28, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKie, R.M. Awareness, knowledge and attitudes to basal cell carcinoma and actinic keratoses among the general public within Europe. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2004, 18, 552–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, A.; Waller, J.; Hiom, S.; Swanston, D. SunSmart? Skin cancer knowledge and preventive behaviour in a British population representative sample. Health Educ. Res. 2005, 20, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfahlberg, A.; Gefeller, O.; Kolmel, K.F. Public awareness of malignant melanoma risk factors in Germany. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1997, 51, 698–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The EndNote Team. EndNote, EndNote X9 ed.; Clarivate: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013.

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Moola, S.; Lisy, K.; Riitano, D.; Tufanaru, C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Spiegelhalter, D.J. A Re-Evaluation of Random-Effects Meta-Analysis. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 2009, 172, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guddat, C.; Grouven, U.; Bender, R.; Skipka, G. A note on the graphical presentation of prediction intervals in random-effects meta-analyses. Syst. Rev. 2012, 1, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, T.H.; Migliavaca, C.B.; Stein, C.; Colpani, V.; Falavigna, M.; Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. Conducting proportional meta-analysis in different types of systematic reviews: A guide for synthesisers of evidence. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2021, 21, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zink, A.; Koch, E.; Seifert, F.; Rotter, M.; Spinner, C.D.; Biedermann, T. Nonmelanoma skin cancer in mountain guides: High prevalence and lack of awareness warrant development of evidence-based prevention tools. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2016, 146, w14380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zink, A.; Thome, F.; Schielein, M.; Spinner, C.D.; Biedermann, T.; Tizek, L. Primary and secondary prevention of skin cancer in mountain guides: Attitude and motivation for or against participation. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 32, 2153–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zink, A.; Wurstbauer, D.; Rotter, M.; Wildner, M.; Biedermann, T. Do outdoor workers know their risk of NMSC? Perceptions, beliefs and preventive behaviour among farmers, roofers and gardeners. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017, 31, 1649–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, C. Skin cancer awareness in the Northern Rivers: The gender divide. Aust. Med. Stud. J. 2015, 5, 55–59. Available online: http://www.amsj.org/archives/3952 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Sideris, E.; Thomas, S.J. Patients’ sun practices, perceptions of skin cancer and their risk of skin cancer in rural Australia. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2020, 31, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brokmeier, L.L.; Görig, T.; Spähn, B.A.; Breitbart, E.W.; Heppt, M.; Diehl, K. What does the general population know about nonmelanoma skin cancer? Representative cross-sectional data from Germany. J. Public Health 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, K.; Dursun, E.; Görig, T. Berufskrankheit UV-induzierter Hautkrebs. Zentralblatt Arbeitsmedizin Arbeitsschutz Ergon. 2024, 74, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, R.C.; Jernigan, S. Brief report: An empirically derived educational program for detecting and preventing skin cancer. J. Behav. Med. 1991, 14, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, A.C.; Kopp, L.J. Awareness, knowledge and attitudes to non-melanoma skin cancer and actinic keratosis among the general public. Int. J. Dermatol. 2005, 44, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashinoff, R.; Levine, V.J.; Steuer, A.B.; Sedwick, C. Teens and tanning knowledge and attitudes. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2009, 2, 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- Spradlin, K.; Bass, M.; Hyman, W.; Keathley, R. Skin cancer: Knowledge, behaviors, and attitudes of college students. South. Med. J. 2010, 103, 999–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppa, M.; Cazzaniga, S.; Fargnoli, M.C.; Naldi, L.; Peris, K. Knowledge, perceptions and behaviours about skin cancer and sun protection among secondary school students from Central Italy. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2013, 27, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, C.; Nahar, V.K.; Ford, M.A.; Bass, M.A.; Brodell, R.T. Skin cancer knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors in collegiate athletes. J. Skin. Cancer 2014, 2014, 248198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anders, M.P.; Nolte, S.; Waldmann, A.; Capellaro, M.; Volkmer, B.; Greinert, R.; Breitbart, E.W. The German SCREEN project—Design and evaluation of the communication strategy. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basyouni, R.N.; Alshamrani, H.M.; Al-Faqih, S.O.; Alnajjar, S.F.; Alghamdi, F.A. Awareness, knowledge, and attitude toward nonmelanoma skin cancer and actinic keratosis among the general population of western Saudi Arabia. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 374–378. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, D.; Jefferson, I.S.; Ramirez, P.; Palomino, A.; Adams, W.; Vera, J.; De La Torre, R.; Lee, K.; Elsensohn, A.; Kazbour, H.; et al. Video Education to Promote Skin Cancer Awareness and Identification in Spanish-speaking Patients. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2020, 13, 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, A.; Kindratt, T.; Pagels, P.; Gimpel, N. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Skin Cancer and Sun Exposure among Homeless Men at a Shelter in Dallas, TX. J. Cancer Educ. 2020, 35, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyprianou, D.; Charalambidou, I.; Famojuro, O.; Wang, H.; Su, D.; Farazi, P.A. Knowledge and Attitudes of Cypriots on Melanoma Prevention: Is there a Public Health Concern? BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roky, A.H.; Islam, M.M.; Ahasan, A.M.F.; Mostaq, S.; Mahmud, Z.; Amin, M.N.; Mahmud, A. Overview of skin cancer types and prevalence rates across continents. Cancer Pathog. Ther. 2025, 3, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Jemal, A.; Torre, L.A.; Forman, D.; Vineis, P. Long-Term Realism and Cost-Effectiveness: Primary Prevention in Combatting Cancer and Associated Inequalities Worldwide. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 107, djv273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, N.K. Gender Differences in Health Literacy Among Korean Adults: Do Women Have a Higher Level of Health Literacy Than Men? Am. J. Mens. Health 2015, 9, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliffe, J.L.; Rossnagel, E.; Kelly, M.T.; Bottorff, J.L.; Seaton, C.; Darroch, F. Men’s health literacy: A review and recommendations. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 1037–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, N. Melanoma awareness programs and their impact on the life of Australian Queenslanders: A concise analysis. Int. J. Health Sci. 2024, 18, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Garbe, C.; Keim, U.; Gandini, S.; Amaral, T.; Katalinic, A.; Hollezcek, B.; Martus, P.; Flatz, L.; Leiter, U.; Whiteman, D. Epidemiology of cutaneous melanoma and keratinocyte cancer in white populations 1943–2036. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 152, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoye, I.; Olsen, C.M.; Whiteman, D.C.; Bijon, A.; Wald, L.; Dartois, L.; Clavel-Chapelon, F.; Boutron-Ruault, M.-C.; Kvaskoff, M. Patterns of Ultraviolet Radiation Exposure and Skin Cancer Risk: The E3N-SunExp Study. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 28, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schapira, M.M.; Swartz, S.; Ganschow, P.S.; Jacobs, E.A.; Neuner, J.M.; Walker, C.M.; Fletcher, K.E. Tailoring Educational and Behavioral Interventions to Level of Health Literacy: A Systematic Review. MDM Policy Pract. 2017, 2, 2381468317714474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, J.; Seidler, A.; Diepgen, T.L.; Bauer, A. Occupational ultraviolet light exposure increases the risk for the development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2011, 164, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German Guideline Program in Oncology (German Cancer Society G.C.A., AWMF). Evidence-based Guideline on Prevention of Skin Cancer Long Version 2.1. 2021. Available online: https://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/hautkrebs-praevention/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Uter, W.; Eversbusch, C.; Gefeller, O.; Pfahlberg, A. Quality of Information for Skin Cancer Prevention: A Quantitative Evaluation of Internet Offerings. Healthcare 2021, 9, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenstock, I.M. The Health Belief Model and Preventive Health Behavior. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 354–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R. Modeling Health Behavior Change: How to Predict and Modify the Adoption and Maintenance of Health Behaviors. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, R.; Klein, W.M. Risk perceptions and health behavior. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 5, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paalosalo-Harris, K.; Skirton, H. Mixed method systematic review: The relationship between breast cancer risk perception and health-protective behaviour in women with family history of breast cancer. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 760–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmonds, K.A.; Rose, J.P.; Aspiras, O.G.; Kumar, M.S. Absolute and comparative risk assessments: Evidence for the utility of incorporating internal comparisons into models of risk perception. Psychol. Health 2022, 37, 1414–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, C.M.; Pandeya, N.; Green, A.C.; Ragaini, B.S.; Venn, A.J.; Whiteman, D.C. Keratinocyte cancer incidence in Australia: A review of population-based incidence trends and estimates of lifetime risk. Public Health Res. Pract. 2022, 32, e3212203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brokmeier, L.L.; Diehl, K.; Spähn, B.A.; Jansen, C.; Konkel, T.; Uter, W.; Görig, T. “Well, to Be Honest, I Don’t Have an Idea of What It Might Be”—A Qualitative Study on Knowledge and Awareness Regarding Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 2290–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zink, A.; Schielein, M.; Wildner, M.; Rehfuess, E.A. ‘Try to make good hay in the shade—It won’t work!’ A qualitative interview study on the perspectives of Bavarian farmers regarding primary prevention of skin cancer. Br. J. Dermatol. 2019, 180, 1412–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haney, M.O.; Bahar, Z.; Beser, A.; Arkan, G.; Cengiz, B. Psychometric Testing of the Turkish Version of the Skin Cancer and Sun Knowledge Scale in Nursing Students. J. Cancer Educ. 2018, 33, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, A.K.; Wilson, C.; Roberts, R.M.; Hutchinson, A.D. The Skin Cancer and Sun Knowledge (SCSK) Scale: Validity, Reliability, and Relationship to Sun-Related Behaviors Among Young Western Adults. Health Educ. Behav. 2014, 41, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefeller, O.; Uter, W.; Pfahlberg, A.B. Long-term development of parental knowledge about skin cancer risks in Germany: Has it changed for the better? Prev. Med. 2016, 89, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Publication | Country | Assessment Date | Population | Method of Recruitment and Information Assessment | Sample Size (% Female) | Age (Years) | ROB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katz, Jernigan (1991) [48] | USA | n.r. ** | Undergraduate college students | Sample of college students from various undergraduate classes at a small private liberal arts college (unclear whether full census, convenience or random sample); self-administered questionnaire | 251 (n.r.) | Range: 16–35 | High |

| MacKie (2004) [30] | UK, France, Italy, Germany, Spain | n.r. * | General population | Selected randomly from telephone directories, in-house databases and random dialing; 10 min structured telephone interview | 1500 (40%) | Range: 40–70 | Unclear |

| Halpern, Kopp (2005) [49] | UK, France, Italy, Germany, Spain, USA, Australia | n.r. * | General population | Selected randomly from telephone directories, in-house databases and random dialing (market research survey); 10 min structured telephone interview | 2100 (40%) | Range: 40–70 | Unclear |

| Ashinoff et al. (2009) [50] | USA | n.r. * | High school students in grades 9 through 12 | Voluntary, anonymous survey administered to more than 450 high school students in two schools; self-administered questionnaire | 368 (‘roughly 50%’) | Mean: 16 Range: 14–18 | Unclear |

| Spradlin et al. (2010) [51] | USA | n.r. * | Undergraduate students at a mid-sized southern university | Participants obtained through lecture hall classes across campus; self-administered questionnaire | 492 (51.4%) | Range: 18–24 | Unclear |

| Suppa et al. (2013) [52] | Italy | n.r. * | Students from 11 secondary schools | Randomly selected throughout the Abruzzo region in Central Italy; self-administered questionnaire | 1204 (51.7%) | Median: 17; Range: 14–21 <18: n = 748 (62.1%) ≥18: n = 456 (37.9%) | Unclear |

| Hobbs et al. (2014) [53] | USA | n.r. * | Athletes from the Southern University in the USA | Convenience sample; self-administered questionnaire | 343 (45.2%) | 18: 10.4%; 19: 28%; 20: 22.3%; 21: 17.8%; 22: 16.9%; 23: 3.2%; 24: 0.3% | High |

| Anders et al. (2015) [54] | Germany | April/May 2003 ** | General population | Households contacted by phone by applying a random digit dialing algorithm; computer-assisted telephone interviews | 600 (55.0%) | Mean: 49.7 ± 17.06; 20–29: n = 79 (13.2%) 30–39: n = 122 (20.4%) 40–49: n = 108 (18.0%) 50–59: n = 90 (15.0%) 60–69: n = 103 (17.1%) ≥70: n = 98 (16.3%) | Low |

| Pollock (2015) [44] | Australia | December 2012–February 2013 * | Patients from two medical practices in the Northern Rivers region | Participants recruited through information posters placed in the waiting rooms; self-administered questionnaire | 91 (57.14% ***) | 18–20: n = 10 21–24: n = 7 25–34: n = 13 35–44: n = 6 45–54: n = 17 ≥55: n = 38 | High |

| Duarte et al. (2018) [29] | Spain and Portugal | November 2014–September 2015 * | Outdoor runners | All athletes registered for four consecutive races; self-administered online questionnaire | 2445 (20%) | <25: n = 123 25–44: n = 1610 ≥45: n = 413 | High |

| Basyouni et al. (2020) [55] | Saudi Arabia | 2018 * | Residents of Jeddah (General population) | General population of Jeddah in multiple locations and different districts of the city (no further details); interviews and self-administered questionnaire | 2443 (68.2%) | 18–34: 73.6% 35–49: 16.1% ≥50: 10.4% | Unclear |

| Garcia et al. (2020) [56] | USA | n.r. ** | Primary Spanish-speaking patients at a family medicine clinic | Convenience sample; self-administered questionnaire | 37 (70%) | Mean: 50.92 ± 10.68 | High |

| Joseph et al. (2020) [57] | USA | n.r. * | Homeless men | Convenience sample in a 335-bed, male only, homeless shelter; either self-administered or researcher-administered questionnaire, depending on the participant’s preference or ability to complete the survey | 75 (0%) | 18–44: n = 34 (45%) ≥45: n = 41 (55%) | High |

| Sideris, Thomas (2020) [45] | Australia | October 2015 * | Patients of a medical practice | Distribution of a voluntary paper-based questionnaire to all patients aged 18+; self-administered questionnaire | 179 (62.57%***) | Range: 18–89 18–30: 15.64% 31–45: 23.46% 46–60: 29.05% 61–75: 20.11% >75: 10.61% Missing: 1.12% | High |

| Kyprianou et al. (2022) [58] | Cyprus | October 2015–April 2016 * | Cypriot residents | Participants recruited in public areas based on proportional quota sampling (no further details); either interviews or self-administered questionnaire | 600 (53.0%) | 18–24: n = 85 (14.0%) 25–29: n = 78 (13.0%) 30–34: n = 59 (10.0%) 35–39: n = 67 (11.0%) 40–44: n = 49 (8.0%) 45–49: n = 51 (9.0%) 50–54: n = 56 (9.0%) 55–59: n = 36 (6.0%) ≥60: n = 118 (20.0%) | High |

| Brokmeier et al. (2024) [46] | Germany | October–December 2022 * | General population | Participants selected using a two-stage random sampling procedure; standardized computer-assisted telephone interviews | 4000 (49.3%) | Range: 16–65 Mean: 42.43 ± 14.02 | Low |

| Diehl et al. (2024) [47] | Germany | October–December 2022 * | Former/current outdoor workers | Participants selected using a two-stage random sampling procedure; standardized computer-assisted telephone interviews | 905 (36.2%) | 16–25: n = 196 (21.7%) 26–35: n = 250 (27.7%) 36–45: n = 174 (19.2%) 46–55: n = 144 (15.9%) 56–65: n = 140 (15.5%) | Unclear |

| Publication | Awareness of the Term | N Analyzed | n (%) Aware | Further Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MacKie (2004) [30] | BCC | 1500 | 22% | |

| Halpern, Kopp (2005) [49] | BCC | 2100 | 30% | |

| Ashinoff et al. (2009) [50] | BCC | 368 | 15.25% * | ‘…almost 85 percent were not familiar with a basal cell carcinoma’ |

| Anders et al. (2015) [54] | At least one of four terms referring to SCC ** | 600 | 194 (32.7%) | ‘Women knew more often all terms for skin cancer compared with men (p < 0.002)’ |

| ‘Basaliom’ | 600 | 76 (12.8%) | ||

| BCC | 600 | 95 (15.9%) | ||

| Basyouni et al. (2020) [55] | BCC | 2443 | 239 (9.8%) | |

| Brokmeier et al. (2024) [46] | ‘white skin cancer’ *** | 4000 | 72.8% | women: 78.2%, men: 67.5%, p < 0.001 |

| ‘light skin cancer’ *** | 4000 | 60.9% | women: 64.3%, men: 57.5%, p < 0.001 | |

| BCC | 4000 | 30.7% | women: 37.9%, men: 23.7%, p < 0.001 | |

| SCC | 4000 | 22.6% | women: 26.9%, men: 18.4%, p < 0.001 | |

| Diehl et al. (2024) [47] | ‘white skin cancer’ *** | 905 | 71.0% | |

| ‘light skin cancer’ *** | 905 | 61.9% | ||

| BCC | 905 | 29.5% | ||

| SCC | 905 | 23.0% |

| Publication | Identified as a Type of Skin Cancer | N Analyzed | n (%) Correct | Further Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katz, Jernigan (1991) [48] | Which of the following is not a major form of skin cancer? (BCC, SCC, MM, adenoid cell carcinoma) | 251 | 62% | |

| Suppa et al. (2013) [52] | BCC | 1204 | 191 (15.9%) | |

| Pollock (2015) [44] | BCC | 91 | 81 (89.01%) * | women: 88%; men: 90% |

| SCC | 91 | 56 (61.54%) * | women: 71%; men: 50% | |

| Duarte et al. (2018) [29] | BCC | 2159 | 37% | |

| SCC | 2159 | 27% | ||

| Sideris, Thomas (2020) [45] | BCC | 179 | 30.7% | |

| SCC | 179 | 20.7% | ||

| Kyprianou et al. (2022) [58] | BCC | 596 | 23 (3.86%) * | |

| SCC | 596 | 49 (8.22%) * |

| Publication | Item | N Analyzed | n (%) Correct | Further Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spradlin et al. (2010) [51] | The most common form of skin cancer is? | 492 | 5.3% | correct answer: BCC |

| Hobbs et al. (2014) [53] | The most common form of skin cancer is? | 343 | 5.2% | correct answer: BCC |

| Joseph et al. (2020) [57] | What is the most common form of skin cancer? | 75 | 16% | correct answer: BCC |

| Brokmeier et al. (2024) [46] | Estimated prevalence of NMSC compared to MM | 3953 | 1081 (27.4%) | correct answer: More prevalent Less prevalent: n = 797 (20.2%); Equally prevalent: n = 971 (24.6%); I do not know: n = 1103 (27.9%) |

| Publication | Item | N Analyzed | n (%) Correct | Further Details | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katz, Jernigan (1991) [48] | Which of the following is not a sign of basal cell carcinoma: (a) an open sore that is slow to heal (b) a shiny bump or nodule on the skin, usually the face (c) a reddish patch or irritated area that does not go away (d) a black mole with hair growing in it | 251 | 59% * | Incorrect answers (d) in total: 41% | |

| Basal cell carcinomas: (a) are rarely found in Caucasians (b) tend to metastasize quickly (c) are the most common and least serious of the skin cancers (d) can be fatal if not treated promptly | 251 | 48% * | Incorrect answers (a,b,d) in total: 52% | ||

| Squamous cell carcinomas: (a) can metastasize and cause death (b) are almost always benign (c) tend to occur more frequently in dark-skinned persons (d) usually begin in a mole | 251 | 14%* | Incorrect answers (b,c,d) in total: 86% | ||

| Garcia et al. (2020) [56] | Correct identification of pictures of lesions as malignant ‘cancer’ or benign ‘not cancer’ | BCC (Picture A) ** | 37 | 49% | |

| BCC (Picture B) ** | 37 | 43% | |||

| SCC (Picture A) ** | 37 | 73% | |||

| SCC (Picture B) ** | 37 | 67% | |||

| Brokmeier et al. (2024) [46] | What do you think are signs of NMSC? | Reddish, rough, scaly skin spots | 3968 | 72.8% | |

| Bleeding or poorly healing skin spots | 3970 | 60.9% | |||

| Alterations in nevi | 3970 | 30.7% | answering ‘no’ was correct | ||

| Light or white spots on the skin | 3967 | 22.6% | answering ‘no’ was correct | ||

| What do you believe contributes to the development of NMSC? | Sunbathing | 3978 | 78.7% | ||

| UV radiation during outdoor occupation | 3973 | 77.1% | |||

| Using tanning beds | 3977 | 73.0% | |||

| Weakened immune system | 3978 | 57.9% | |||

| What do you reckon are possible consequences of white skin cancer ***? | Surgery | 3967 | 55.5% | ||

| Metastatic spread | 3954 | 42.2% | |||

| Radiation therapy or chemotherapy | 3967 | 45.4% | |||

| Recurrence of NMSC | 3954 | 56.3% | |||

| NMSC can progress to MM | 3959 | 14.7% | answering ‘no’ was correct | ||

| Estimated severity of NMSC compared to MM | 3963 | 1148 (29.0%) | correct answer: Less severe; Equally severe 1483 (37.4%) More severe 492 (12.4%) I do not know 839 (21.2%) | ||

| Diehl et al. (2024) [47] | What do you think are signs of NMSC? | Reddish, rough, scaly skin spots | 905 | 40.7% | |

| Bleeding or poorly healing skin spots | 905 | 41.7% | |||

| Alterations in nevi | 905 | 23.2% | answering ‘no’ was correct | ||

| Light or white spots on the skin | 905 | 18.0% | answering ‘no’ was correct | ||

| Sunlight can contribute to the development of ‘white skin cancer’ *** in people who work outdoors. | 905 | 71.4% | |||

| Publication | Item | N analyzed | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brokmeier et al. (2024) [46] | Concern about NMSC | 3939 | Yes: n = 986 (25.0%); No: n = 1482 (37.6%); I have never thought about it: n = 1471 (37.3%) |

| Diehl et al. (2024) [47] | Concern about NMSC | 905 | Yes: 30.0%; No: 38.0%; I have never thought about it: 32.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brokmeier, L.L.; Ilic, L.; Haas, S.; Uter, W.; Heppt, M.V.; Gefeller, O.; Kaiser, I. Knowledge and Risk Perception Regarding Keratinocyte Carcinoma in Lay People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1912. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151912

Brokmeier LL, Ilic L, Haas S, Uter W, Heppt MV, Gefeller O, Kaiser I. Knowledge and Risk Perception Regarding Keratinocyte Carcinoma in Lay People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1912. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151912

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrokmeier, Luisa Leonie, Laura Ilic, Sophia Haas, Wolfgang Uter, Markus Vincent Heppt, Olaf Gefeller, and Isabelle Kaiser. 2025. "Knowledge and Risk Perception Regarding Keratinocyte Carcinoma in Lay People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1912. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151912

APA StyleBrokmeier, L. L., Ilic, L., Haas, S., Uter, W., Heppt, M. V., Gefeller, O., & Kaiser, I. (2025). Knowledge and Risk Perception Regarding Keratinocyte Carcinoma in Lay People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare, 13(15), 1912. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151912