Assessment of the Physical and Emotional Health-Related Quality of Life Among Congestive Heart Failure Patients with Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction at a Quaternary Care Teaching Hospital in Coastal Karnataka in India

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area and Design

2.2. Participants and Sample Size

2.3. Tools Used

2.4. Data Analysis and Statistical Methods

2.5. Study Procedure and Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Profile

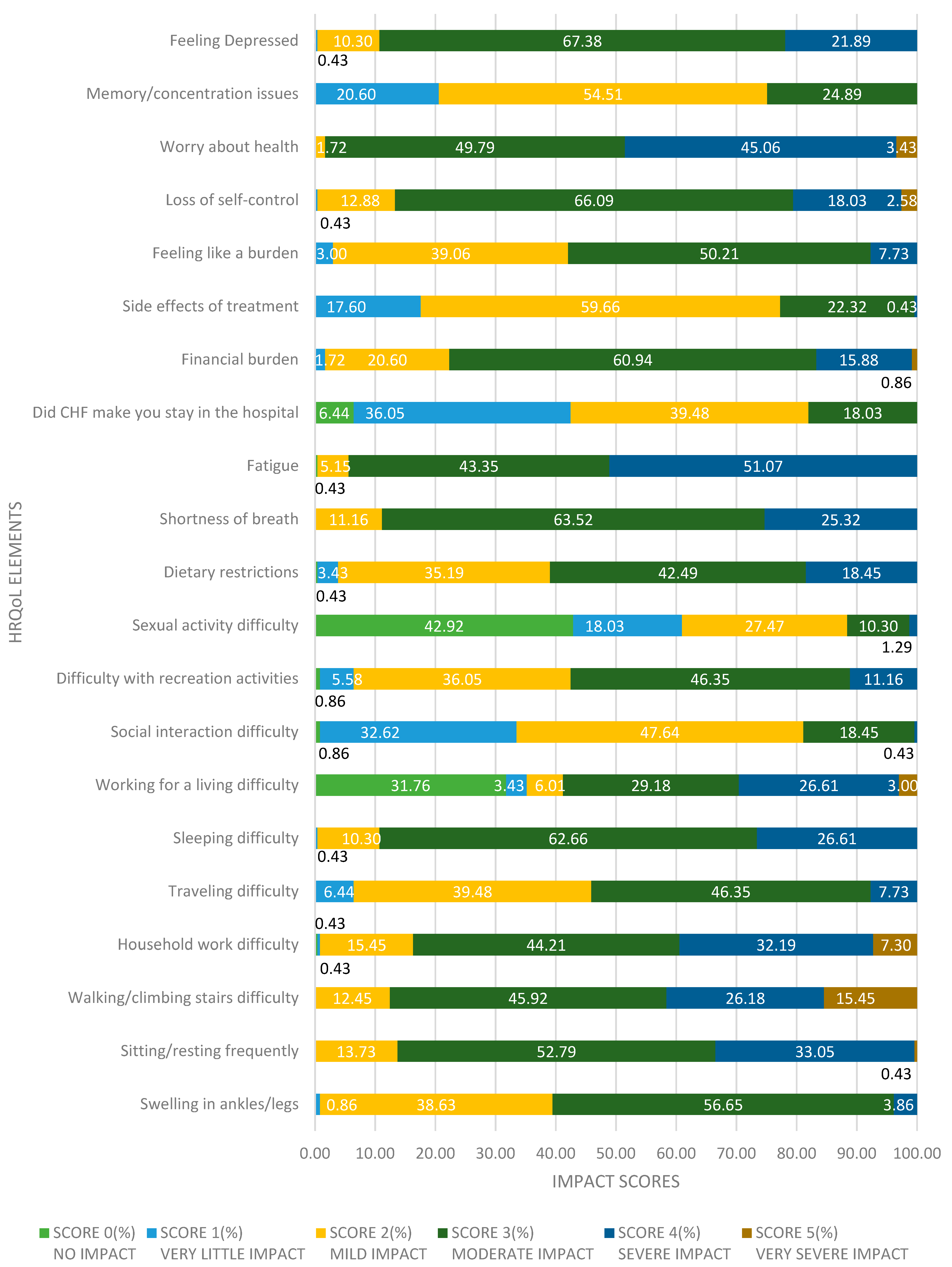

3.2. Item-Level Analysis of MLHFQ Responses

- Physical Symptoms

- Swelling in ankles/legs: Over half of the patients (56.7%, n = 132) reported a score of 3, indicating moderate swelling. An additional 38.6% (n = 90) reported a score of 2 (mild swelling). This suggests that peripheral edema is a prevalent issue but generally remains at a manageable level.

- Sitting or resting frequently: A significant portion (52.8%, n = 123) experienced a moderate need to rest (score 3), and 33.0% (n = 77) reported a higher limitation (score 4). This reflects substantial fatigue or reduced stamina affecting daily functioning.

- Walking/climbing stairs difficulty: Nearly half (45.9%, n = 107) reported moderate difficulty (score 3), while 26.2% (n = 61) and 15.5% (n = 36) experienced severe to very severe limitations (scores 4 and 5, respectively). This underscores mobility as a key challenge.

- Fatigue: Among the most debilitating symptoms, fatigue was rated score 4 by 51.1% (n = 119) and score 3 by 43.3% (n = 101), indicating that a majority of patients experience moderate to severe exhaustion.

- Sleep and Activity Limitations

- Sleeping difficulty: Most participants (62.7%, n = 146) rated this as moderate (score 3), and 26.6% (n = 62) rated it as severe (score 4), reflecting disrupted sleep patterns common in CHF.

- Household work difficulty: 44.2% (n = 103) reported score 3 and 32.2% (n = 75) reported score 4. This suggests limitations in fulfilling domestic responsibilities.

- Travelling difficulty: 46.4% (n = 108) rated this moderately difficult (score 3), while 39.5% (n = 92) reported mild difficulty (score 2). Severe restrictions were less common (7.7%, score 4).

- Recreational activities: 46.4% (n = 108) of patients experienced a moderate impact (score 3) and 36.1% (n = 84) had mild limitations (score 2), suggesting that leisure activities are notably affected but not severely curtailed for most.

- Working for a living: Around 29.2% (n = 68) reported moderate difficulty (score 3), and 26.6% (n = 62) reported severe difficulty (score 4). Notably, 31.8% (n = 74) reported no impact (score 0), which may include retired or non-working individuals.

- Emotional and Psychosocial Impact

- Social interaction difficulty: 47.6% (n = 111) and 32.6% (n = 76) reported mild to moderate impact (scores 2 and 1, respectively), while only a small percentage indicated severe social limitations, suggesting CHF moderately interferes with interpersonal relations.

- Feeling depressed: Depression was highly prevalent, with 67.4% (n = 157) scoring 3 and 21.9% (n = 51) scoring 4. This indicates a significant emotional burden affecting most patients.

- Worry about health: Nearly all patients reported worry, with 49.8% (n = 116) scoring 3 and 45.1% (n = 105) scoring 4, highlighting high levels of health-related anxiety.

- Feeling like a burden: 50.2% (n = 117) scored 3 and 39.1% (n = 91) scored 2, revealing that emotional guilt or perceived burden on caregivers is common.

- Loss of self-control: A striking 66.1% (n = 154) reported a score of 3, and 18.0% (n = 42) scored 4, indicating that psychological feelings of helplessness are frequent and intense.

- Cognitive and Economic Burden

- Memory/concentration issues: Most patients (54.5%, n = 127) reported mild cognitive impact (score 2), with another 24.9% (n = 58) experiencing moderate difficulty (score 3), suggesting that cognitive symptoms are prevalent, though mostly not severe.

- Financial burden: A large proportion of patients (60.9%, n = 142) rated financial impact at score 3 and 15.9% (n = 37) at score 4. This underlines the significant economic strain heart failure places on patients.

- Hospital stays due to CHF: 39.5% (n = 92) reported a score of 3 and 36.1% (n = 84) a score of 2, reflecting frequent or impactful hospitalizations among this population.

- Side effects of treatment: Most patients (59.7%, n = 139) reported mild treatment side effects (score 2), while 22.3% (n = 52) noted moderate ones (score 3), indicating treatment tolerability but with some burden.

3.3. Descriptive Comparison of HRQoL Between HFrEF and HfpEF

3.4. Independent Samples t-Test for HRQoL

3.5. Factors Associated with HRQoL

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall HRQoL Among CHF Patients

4.2. HRQoL Differences Between HFpEF and HFrEF

4.3. Sociodemographic Correlates of HRQoL

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Savarese, G.; Becher, P.M.; Lund, L.; Seferović, P.M.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Coats, A.J.S. Global burden of heart failure: A comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 3272–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarab, A.S.; Mukattash, T.L.; Al-Azayzih, A.; Khdour, M. Health-related quality of life and its associated factors among outpatients with heart failure: A cross-sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2023, 23, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivadasanpillai, H.; Ganapathi, S.; Sharma, M.; Reethu, S.; Prasad, D.; Philip, G.; Jeemon, P. Development and validation of heart failure-specific quality-of-life measurement tool in India. Am. Heart J. Plus 2023, 23, 100329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, P.J.J.; George, L.S.; Paramasivam, G.; Devasia, T.; Ravishankar, N.; Nayak, B.S.; Noronha, J.; Kusumavathi, P.; George, A. Symptom perception, health-related quality of life and predicted survival in heart failure patients. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2024, 22, 101754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xin, Y.; Hu, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Y. Quality of life and outcomes in heart failure patients with ejection fractions in different ranges. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, H.P.; Nguyen, K.M.; Tran, H.; Hoang, S.V. Assessment of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure: A cross-sectional study in Vietnam. Cureus 2023, 15, e51098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, H.G.; Lee, C.S.; Moser, D.K.; Albert, N.M.; Lennie, T.A.; Bentley, B.; Worrall-Carter, L.; Riegel, B. Relationship between self-care and health-related quality of life in older adults with moderate to advanced heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2012, 27, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.; Moser, D.K.; Pressler, S.J.; Dunbar, S.B.; Kim, J.; Ounpraseuth, S.T.; Lennie, T.A. Dose-dependent relationship of physical and depressive symptoms with health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2013, 12, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juenger, J.; Schellberg, D.; Kraemer, S.; Haunstetter, A.; Zugck, C.; Herzog, W.; Haass, M. Health-related quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure: Comparison with other chronic diseases and relation to functional variables. Heart 2002, 87, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, M.H.; Alharbi, F.B.; Altuwayjiri, A.M.; Alharbi, Y.; Alhofair, Y.; Alanazi, A.B.; AlJlayl, F.; Khalil, R.; Al-Wutayd, O. Assessment of health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure: A cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2022, 20, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mocumbi, A. Cardiovascular health care in low- and middle-income countries. Circulation 2024, 149, 557–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventoulis, I.; Kamperidis, V.; Abraham, M.; Abraham, T.; Boultadakis, A.; Tsioukras, E.; Katsiana, A.; Georgiou, K.; Parissis, J.; Polyzogopoulou, E. Differences in health-related quality of life among patients with heart failure. Medicina 2024, 60, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, D.K.; Heo, S.; Lee, K.S.; Hammash, M.; Riegel, B.; Lennie, T.A.; Arslanian-Engoren, C.; Mudd-Martin, G.; Albert, N.M.; Watkins, J.F. ‘It could be worse … lot’s worse!’ Why is health-related quality of life better in older compared with younger individuals with heart failure. Age Ageing 2013, 42, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golla, M.S.G.; Shams, P. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). In Heart Failure: Pathophysiology and Treatment; National Center for Biotechnology Information: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK599960/ (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Behlouli, H.; Feldman, D.E.; Ducharme, A.; Frenette, M.; Giannetti, N.; Grondin, F.; Michel, C.; Sheppard, R.; Pilote, L. Identifying relative cut-off scores with neural networks for interpretation of the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire. In Proceedings of the 2009 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 3–6 September 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 6242–6246. [Google Scholar]

- Thangaraj, E.; Harish, K.B.; MadavaKousik, C.M.K.; Leena, V.; Alexander, T. Health-related quality of life in heart failure patients: A prospective study. IOSR J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. 2023, 18, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patidar, A.B.; Kaur, H. Self-care of heart failure and health-related quality of life among congestive heart failure patients in Punjab, India. Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 2021, 11, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, R.; Jeemon, P.; Ganapathi, S.; Roby, A.; Dhaliwal, R.S.; Punnoose, E.; Philip, G.; Abdhullakutty, J.; Joseph, J.; Sreedharan, M.; et al. Quality of life among heart failure patients in India. Heart Fail. J. India 2023, 1, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napier, R.; McNulty, S.; Eton, D.T.; Redfield, M.M.; AbouEzzeddine, O.F.; Dunlay, S.M. Comparing measures to assess health-related quality of life in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2018, 6, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulugeta, H.; Sinclair, P.M.; Wilson, A. Health-related quality of life and its influencing factors among people with heart failure in Ethiopia: Using the revised Wilson and Cleary model. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudiyawati, D.; Mujannidah, A. Health-related quality of life among congestive heart failure patients with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. Front. Nurs. 2024, 10, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.; Lennie, T.A.; Moser, D.K.; Kennedy, R.L. Gender differences in the effects of physical and emotional symptoms on health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2007, 6, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajita, M.I.; Cajita, T.R.; Han, H.R. Health Literacy and Heart Failure: A Systematic Review. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2016, 31, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | HFrEF | HFpEF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency(n) | Percentage (%) | Frequency(n) | Percentage (%) | |

| Ejection fraction type | 136 | 58.4 | 97 | 41.6 |

| Age (years old) | ||||

| 25–35 | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 |

| 36–45 | 11 | 4.7 | 0 | 0 |

| 46–55 | 36 | 15.5 | 24 | 10.3 |

| 56–65 | 50 | 21.5 | 44 | 18.9 |

| 66–75 | 29 | 12.4 | 25 | 10.7 |

| 76–85 | 8 | 3.4 | 4 | 1.7 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 121 | 51.9 | 44 | 18.9 |

| Female | 15 | 6.4 | 53 | 22.7 |

| Employment Status | ||||

| Unemployed | 39 | 16.7 | 29 | 12.4 |

| Employed | 61 | 26.2 | 40 | 17.2 |

| Retired | 36 | 15.5 | 28 | 12 |

| Education Level | ||||

| No Formal Education | 13 | 5.6 | 10 | 4.3 |

| Primary school | 55 | 23.6 | 41 | 17.6 |

| High School | 46 | 19.7 | 36 | 15.5 |

| Higher Education (Diploma/University) | 22 | 9.4 | 10 | 4.3 |

| NYHA functional class | ||||

| NYHA I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NYHA II | 41 | 17.6 | 26 | 11.2 |

| NYHA III | 73 | 31.3 | 64 | 27.5 |

| NYHA IV | 22 | 9.4 | 7 | 3 |

| Duration of Congestive HF disease (Years) | ||||

| 1 | 13 | 5.6 | 15 | 6.4 |

| 2 | 41 | 17.6 | 34 | 14.6 |

| 3 | 36 | 15.5 | 27 | 11.6 |

| 4 | 25 | 10.7 | 13 | 5.6 |

| 5 | 16 | 6.9 | 8 | 3.4 |

| 6 | 5 | 2.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Unmarried | 3 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Married | 123 | 52.8 | 80 | 34.3 |

| Widowed | 10 | 4.3 | 17 | 7.3 |

| MLHFQ Item | HFrEF Mean Score | HFpEF Mean Score | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 4.1 | 2.1 | 2.0 |

| Shortness of Breath | 3.9 | 2.6 | 1.3 |

| Depression | 3.6 | 2.7 | 0.9 |

| Travel Difficulty | 3.3 | 2.4 | 0.9 |

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Estimate | SE | Lower | Upper | t | p |

| Intercept | 41.203 | 3.1182 | 35.058 | 47.348 | 13.214 | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.311 | 0.0565 | 0.2 | 0.422 | 5.505 | <0.001 |

| Gender: | ||||||

| Male—Female | −4.591 | 0.7803 | −6.128 | −3.053 | −5.883 | <0.001 |

| Educational Level: | ||||||

| Higher Education(Diploma/University) High School | 0.43 | 1.1348 | −1.806 | 2.667 | 0.379 | 0.705 |

| No Formal Education—High School | 2.332 | 1.369 | −0.366 | 5.03 | 1.703 | 1.090 |

| Primary school—High School | 0.739 | 0.7958 | −0.829 | 2.307 | 1929 | 0.354 |

| Employment Status: | ||||||

| Retired—Employed | −0.703 | 1.0308 | −2.735 | 1.328 | −0.682 | 0.496 |

| Unemployed—Employed | −0.688 | 0.909 | −2.479 | 1.103 | −0.757 | 0.450 |

| Marital Status: | ||||||

| Unmarried—Married | −2.049 | 3.1519 | −8.26 | 4.162 | −0.65 | 0.516 |

| Widowed—Married | −1.445 | 1.1746 | −3.759 | 0.87 | −1.23 | 0.22 |

| Ejection Fraction Type | ||||||

| HFrEF-HFpEF | −7.902 | 0.5752 | −9.035 | −6.768 | −13.739 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kamath, R.; Poojary, V.; Shekar, N.; Lalani, K.; Bari, T.; Salins, P.; Rodrigues, G.; Teotia, D.; Kini, S. Assessment of the Physical and Emotional Health-Related Quality of Life Among Congestive Heart Failure Patients with Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction at a Quaternary Care Teaching Hospital in Coastal Karnataka in India. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1874. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151874

Kamath R, Poojary V, Shekar N, Lalani K, Bari T, Salins P, Rodrigues G, Teotia D, Kini S. Assessment of the Physical and Emotional Health-Related Quality of Life Among Congestive Heart Failure Patients with Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction at a Quaternary Care Teaching Hospital in Coastal Karnataka in India. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1874. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151874

Chicago/Turabian StyleKamath, Rajesh, Vineetha Poojary, Nishanth Shekar, Kanhai Lalani, Tarushree Bari, Prajwal Salins, Gwendolen Rodrigues, Devesh Teotia, and Sanjay Kini. 2025. "Assessment of the Physical and Emotional Health-Related Quality of Life Among Congestive Heart Failure Patients with Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction at a Quaternary Care Teaching Hospital in Coastal Karnataka in India" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1874. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151874

APA StyleKamath, R., Poojary, V., Shekar, N., Lalani, K., Bari, T., Salins, P., Rodrigues, G., Teotia, D., & Kini, S. (2025). Assessment of the Physical and Emotional Health-Related Quality of Life Among Congestive Heart Failure Patients with Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction at a Quaternary Care Teaching Hospital in Coastal Karnataka in India. Healthcare, 13(15), 1874. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151874