A Systematic Review of Tuberculosis Stigma Reduction Interventions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

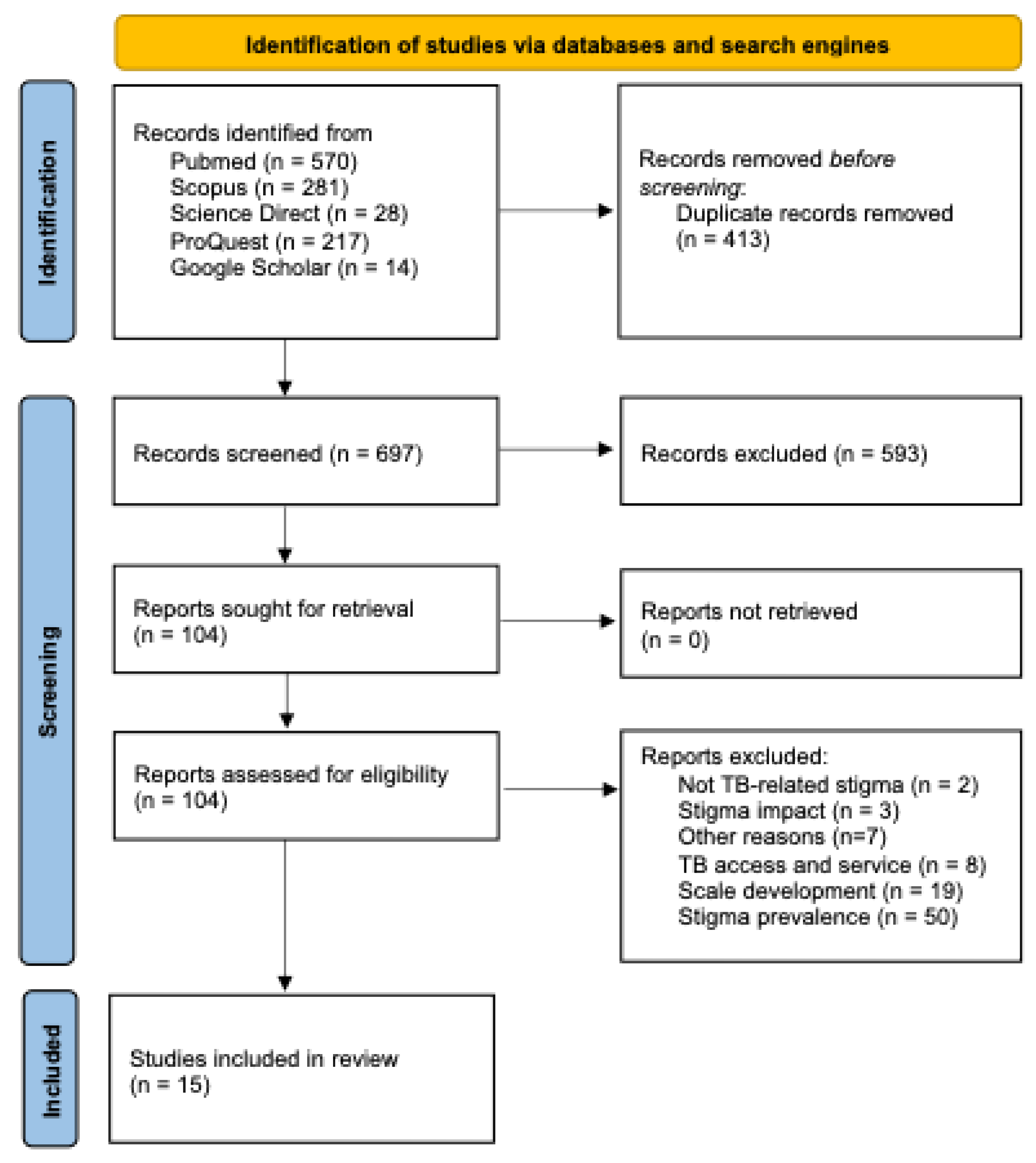

2.1. Search Strategy, Study Selection, and Data Collection

2.2. Data Synthesis

2.3. Risk of Bias Evaluation

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| DOT | Directly Observed Therapy |

| DR-TB | Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis |

| HW | Health Worker |

| IPC | Infection Prevention and Control |

| KAPS | Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Survey |

| MMAT | Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool |

| MDR | Multidrug-Resistant |

| PICOS | Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, and Study Design |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PWTB | People with Tuberculosis |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| VDOT | Video Directly Observed Therapy |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- World Health Organization. 2024 Global Tuberculosis Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease Income-Related Disparity in Country TB Rates. Available online: https://theunion.org/news/income-related-disparity-in-country-tb-rates (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Craig, G.M.; Daftary, A.; Engel, N.; O’Driscoll, S.; Ioannaki, A. Tuberculosis Stigma as a Social Determinant of Health: A Systematic Mapping Review of Research in Low Incidence Countries. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 56, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.; Huang, X.L.; Yan, W.; Zhang, Y.X.; Gong, Y.M.; Su, S.Z.; Huang, Y.T.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, Y.J.; Yuan, Z.; et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Prevalence of Stigma in Infectious Diseases, Including COVID-19: A Call to Action. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 27, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wu, L.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yin, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Influence of Tuberculosis Knowledge on Acceptance of Preventive Treatment and the Moderating Role of Tuberculosis Stigma among China’s General Population: Cross-Sectional Analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.E.; Shanmugam, P.; Malaisamy, M.; Ovung, S.; Suresh, C.; Subbaraman, R.; Adinarayanan, S.; Nagarajan, K. Psycho-Socio-Economic Issues Challenging Multidrug Resistant Tuberculosis Patients: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toure, A.F. Multidimensional Impact of Tuberculosis on Quality of Life: Physical, Psychological, Social and Economic Aspects. J. Infect. Dis. Pneumol. 2025, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Villar, M.; Carroll, J.J. Shifting Stigma: Why Ukrainian Health Care Workers Favor a High Barrier Treatment Modality for Tuberculosis. Med. Anthr. Theory 2023, 10, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumla, A.; Sahu, S.; Ditiu, L.; Singh, U.; Park, Y.J.; Yeboah-Manu, D.; Osei-Wusu, S.; Asogun, D.; Nyasulu, P.; Tembo, J.; et al. Inequities Underlie the Alarming Resurgence of Tuberculosis as the World’s Top Cause of Death from an Infectious Disease–Breaking the Silence and Addressing the Underlying Root Causes. IJID Reg. 2025, 14, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtwright, A.; Turner, A.N. Tuberculosis and Stigmatization: Pathways and Interventions. Public Health Rep. 2010, 125, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, V.K.; Chopra, K.K.; Rajpal, S. Tuberculosis and Stigma: Break the Silence…. Indian J. Tuberc. 2025, 72, S1–S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datiko, D.G.; Jerene, D.; Suarez, P. Stigma Matters in Ending Tuberculosis: Nationwide Survey of Stigma in Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daftary, A.; Mitchell, E.M.H.; Reid, M.J.A.; Fekadu, E.; Goosby, E. To End TB, First-Ever High-Level Meeting on Tuberculosis Must Address Stigma. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 99, 1114–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stop TB Partnership the Global Plan to End, TB. Available online: https://omnibook.com/embedview/dc664b3a-14b4-4cc0-8042-ea8f27e902a6/page-en.html#z-296d (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Liboon Aranas, L.; Alam, K.; Gyawali, P.; Alam, R.M. Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Stigma Among HealthCare Workers Toward the Development of a Stigma-Reduction Strategy: A Scoping Review. Inq. J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2023, 60, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraade, M.H.; Jeffree, M.S.; Lin, L.J.; Fiidow, O.A.; Avoi, R.; Rao, P.V.; Hassan, M.R. Intervention Approaches of Stigma Related to Tuberculosis in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review. Malays. J. Public Health Med. 2022, 22, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerland, N.; Wouters, E.; Mitchell, E.M.H.; Ngicho, M.; Redwood, L.; Masquillier, C.; Van Hoorn, R.; Van Den Hof, S.; Van Rie, A. Evidence-Based Interventions to Reduce Tuberculosis Stigma: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2017, 21, S81–S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Berger, C.A.; Kityamuwesi, A.; Ggita, J.; Tinka, L.K.; Turimumahoro, P.; Feler, J.; Chehab, L.; Chen, A.Z.; Gupta, N.; et al. Iterative Adaptation of a Tuberculosis Digital Medication Adherence Technology to Meet User Needs: Qualitative Study of Patients and Health Care Providers Using Human-Centered Design Methods. JMIR Form. Res. 2020, 4, e19270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabin, L.L.; Thulasingam, M.; Carwile, M.; Babu, S.P.; Knudsen, S.; Dong, L.; Stephens, J.; Fernandes, P.; Cintron, C.; Horsburgh, C.R.; et al. ‘People Listen More to What Actors Say’: A Qualitative Study of Tuberculosis-Related Knowledge, Behaviours, Stigma, and Potential Interventions in Puducherry. India. Glob. Public Health 2022, 17, 2898–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Westhuizen, H.-M.; Ehrlich, R.; Somdyala, N.; Greenhalgh, T.; Tonkin-Crine, S.; Butler, C.C. Stigma Relating to Tuberculosis Infection Prevention and Control Implementation in Rural Health Facilities in South Africa—A Qualitative Study Outlining Opportunities for Mitigation. BMC Glob. Public Health 2024, 2, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawey, F.M.; Karimah, A.; Kusmiati, T. Workplace Interventions to Overcome Stigma and Depression in Patients with Multiple Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis (MDR TB). Bali Med. J. 2023, 12, 1353–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, S.E.; Vanqa, N.; Makanda, G.; Tisile, P.; Ngwatyu, L.; Foster, I.; Mcinziba, A.A.; Biewer, A.; Mbuyamba, R.; Galloway, M.; et al. “As a Patient I Do Not Belong to the Clinic, I Belong to the Community”: Co-Developing Multi-Level, Person-Centred Tuberculosis Stigma Interventions in Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Glob. Public Health 2024, 2, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.W.; Ramos, J.G.; Castillo, F.; Castellanos, E.F.; Escalante, P. Tuberculosis Patient and Family Education through Videography in El Salvador. J Clin. Tuberc. Other Mycobact. Dis. 2016, 4, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, I.; Biewer, A.; Vanqa, N.; Makanda, G.; Tisile, P.; Hayward, S.E.; Wademan, D.T.; Anthony, M.G.; Mbuyamba, R.; Galloway, M.; et al. “This Is an Illness. No One Is Supposed to Be Treated Badly”: Community-Based Stigma Assessments in South Africa to Inform Tuberculosis Stigma Intervention Design. BMC Glob. Public Health 2024, 2, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuady, A.; Anindhita, M.; Hanifah, M.; Putri, A.M.N.; Karnasih, A.; Agiananda, F.; Yani, F.F.; Haya, M.A.N.; Pakasi, T.A.; Wingfield, T. Codeveloping a Community-Based, Peer-Led Psychosocial Support Intervention to Reduce Stigma and Depression among People with Tuberculosis and Their Households in Indonesia: A Mixed-Methods Participatory Action Study. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2025, 35, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, N.; Chellaiyan, V.G.; Daral, S.; Adhikary, M.; Das, T.K. Home Based Care as an Approach to Improve the Efficiency of Treatment for MDR Tuberculosis: A Quasi-Experimental Pilot Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, LC05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik Kara, G.; Murat Yalcin, B. Comparison of In-Person vs. Video Directly Observed Therapy (VDOT) on Stigma Levels in Tuberculosis Patients. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2022, 35, 951–960. [Google Scholar]

- Moonsarn, S.; Kasetjaroen, Y.; Bettex-Baars, A.M.; Phanumartwiwath, A. A Communication-Based Intervention Study for Reducing Stigma and Discrimination against Tuberculosis among Thai High-School Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, S.H.-F.; France, N.F.; Hodgson, I.; Ali, F.; Dewi, C.; Abdurrakhman, I.; Runtu, Y.M.; Juan, A.; Sugiharto, J.; Byrne, E.; et al. Piloting “From the Inside Out”—A Toolkit Addressing Tuberculosis-Related Self-Stigma. BMC Glob. Public Health 2024, 2, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vibulchai, N.; Dana, K.; Sanchan, M.; Churari, C.; Jadboonnak, B.; Sawangsri, W.; Pothiporn, W.T.; Sutthicharoen, U. The Effect of the Peer Support Intervention on Internalized Stigma among Thai Patients with Tuberculosis: A Repeated Measures Design. Belitung Nurs. J. 2024, 10, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, N.A.; Zakaria, R.; Muhamad, R.; Husain, N.R.N.; Ishak, A.; Wan Mohammad, W.M.Z. The Effectiveness of Tuberculosis Education Programme in Kelantan, Malaysia on Knowledge, Attitude, Practice and Stigma towards Tuberculosis among Adolescents. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 27, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraade, M.H.; Jeffree, M.S.; Avoi, R.; Fiidow, O.A. Tuberculosis Stigma Intervention, Hargeisa Hospital Somalia-A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Malays. J. Med. Health Sci. 2023, 19, 2636–9346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coreil, J.; Mayard, G.; Simpson, K.M.; Lauzardo, M.; Zhu, Y.; Weiss, M. Structural Forces and the Production of TB-Related Stigma among Haitians in Two Contexts. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 1409–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riset, J.; Dan, K.; Kesehatan, P.; Tasyabitah, J.; Maulia, T. Barriers and Mitigation Strategies in Stigma toward Infectious Diseases: Psychological, Social, and Healthcare Implications. J. Ris. Kualitatif Dan Promosi Kesehat. 2022, 1, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omosigho, P.O.; John, O.O.; Musa, M.B.; Aboelhassan, Y.M.E.I.; Olabode, O.N.; Bouaddi, O.; Mengesha, D.T.; Micheal, A.S.; Modber, M.A.K.A.; Sow, A.U.; et al. Stigma and Infectious Diseases in Africa: Examining Impact and Strategies for Reduction. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 85, 6078–6082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttall, C.; Fuady, A.; Nuttall, H.; Dixit, K.; Mansyur, M.; Wingfield, T. Interventions Pathways to Reduce Tuberculosis-Related Stigma: A Literature Review and Conceptual Framework. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2022, 11, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Strategy to End Stigma and Discrimination Associated with Tuberculosis; Ministry of Health and Family Welfare: New Delhi, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Anindhita, M.; Haniifah, M.; Putri, A.M.N.; Karnasih, A.; Agiananda, F.; Yani, F.F.; Haya, M.A.N.; Pakasi, T.A.; Widyahening, I.S.; Fuady, A.; et al. Community-Based Psychosocial Support Interventions to Reduce Stigma and Improve Mental Health of People with Infectious Diseases: A Scoping Review. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2024, 13, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Fields | Filters |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | Title, Abstract, and Keywords | Language: English Date: 2015 to present |

| Scopus | Title, Abstract, and Keywords | Language: English Date: 2015 to present |

| Science Direct | Title, Abstract, and Keywords | Language: English Date: 2015 to present |

| ProQuest | Title, Abstract, and Keywords | Language: English Date: 2015 to present |

| Google Scholar | Title | Date: 2015 to present |

| PICOS Framework | Studies to Be Included | Studies to Be Excluded |

|---|---|---|

| Population | General public, adolescents, TB patients/survivors, caregivers, and healthcare providers | HIV patients and HIV/TB co-infected individuals |

| Intervention | TB-stigma-focused program development, TB treatment interventions demonstrating stigma reduction, and dedicated stigma reduction initiatives | TB treatment interventions without assessed stigma impacts |

| Comparator | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Outcome | Stigma types addressed, target populations, and intervention components | TB treatment efficacy or knowledge outcomes without stigma metrics |

| Study design | Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies | Reviews, editorials, commentaries, conference abstracts, and non-English publications |

| Author, Year | Question 1 | Question 2 | Question 3 | Question 4 | Question 5 | Question 6 | Question 7 | Assessment Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Studies | Clear RQ? | RQ Addressed? | Approach Appropriate? | Method Adequate? | Findings Adequate? | Results Substantiated? | Analysis Coherent? | Total “Yes” Answers |

| Patel, 2020 [18] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Sabin, 2021 [19] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| van der Westhuizen, 2024 [20] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | 6 |

| Mawey, 2023 [21] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | Yes | 5 |

| Hayward, 2024 [22] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Mixed Methods Studies | Clear RQ? | RQ Addressed? | Rationale for MM? | Integration of Components? | Adequate Interpretation? | Divergences Addressed? | Quality Adherence? | Total “Yes” Answers |

| Wilson, 2016 [23] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | 6 |

| Foster, 2024 [24] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Fuady, 2025 [25] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Quantitative Descriptive Studies | Clear RQ? | RQ Addressed? | Sampling Relevant? | Sample Representative? | Measurement Appropriate? | Low Nonresponse Bias? | Analysis Appropriate? | Total “Yes” Answers |

| Taneja, 2017 [26] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | 6 |

| Kara, 2022 [27] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | 5 |

| Moonsarn, 2023 [28] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | 6 |

| Macdonald, 2024 [29] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | 6 |

| Vibulchai, 2024 [30] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | 6 |

| Quantitative Non-Randomized Studies | Clear RQ? | RQ Addressed? | Participants Representative? | Measurement Appropriate? | Outcome Data Complete? | Confounders Accounted? | Intended Intervention Delivered? | Total “Yes” Answers |

| Idris, 2020 [31] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | 6 |

| Quantitative RCTs | Clear RQ? | RQ Addressed? | Randomization Appropriate? | Comparable Groups? | Outcome Data Complete? | Blind Assessment? | Participant Adherence? | Total “Yes” Answers |

| Faraade, 2023 [32] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Author, Year | Country | Study Design | Methodology | Population | Outcome | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development of Stigma Interventions | ||||||

| Sabin, 2021 [19] | India | Qualitative | In-depth interviews | Persons living with active TB | Intervention development | 47 TB patients |

| Foster, 2024 [24] | South Africa | Mixed-methods | Mixed-methods | People affected with TB | Design and implementation of contextually relevant stigma reduction intervention | 93 PWTB and 24 caregivers |

| Hayward, 2024 [22] | South Africa | Qualitative | Community-based participatory research approach | People diagnosed with TB, caregivers, and health workers | Co-development of person-centered stigma intervention | 87 people diagnosed with TB, caregivers, and health workers |

| van der Westhuizen, 2024 [20] | South Africa | Qualitative | In-depth interviews | Health workers and PWTB | Recommendations for stigma reduction associated with TB IPC | 18 HW and 15 PWTB |

| Fuady, 2025 [25] | Indonesia | Mixed-methods | Mixed-methods participatory action study | Relevant stakeholders with suitable and diverse TB expertise and/or experience and national participatory workshop with TB patients | Co-development of community-based, peer-led support intervention to reduce TB stigma | 25 stakeholders and 20 TB patients |

| Tuberculosis Treatment-Related Interventions with Demonstrated Impact on Stigma Reduction | ||||||

| Wilson, 2016 [23] | El-Salvador | Mixed-methods | Pilot intervention study with three-tier assessment | Health providers, TB patients, and family members | Improved TB and treatment knowledge among TB patients and their families | 1916 TB patients and family members |

| Taneja, 2017 [26] | India | Quantitative | Quasi-experimental pilot study | Diagnosed MDR TB patients | Assessment of outcomes of Home-Based Care (intervention) versus No Home-Based Care (control) on treatment of MDR TB | 50 intervention and 50 control |

| Patel, 2020 [18] | Uganda | Qualitative | Human-centered design | TB patients, family members, health workers, and community leaders | Identification of essential insights and potential areas for redesign of original 99DOTS platform | 67 TB patients, family members, health workers, and community leaders |

| Stigma Reduction Interventions | ||||||

| Idris, 2020 [31] | Malaysia | Quantitative | School-based, non-randomized controlled study | High school students | Improvement in TB knowledge, attitudes, practices, and stigma | 236 students |

| Kara, 2022 [27] | Turkey | Qualitative | Cross-sectional | TB patients receiving directly observed therapy | Reduction in stigma | 30 DOT and 52 VDOT TB patients |

| Faraade, 2023 [32] | Somalia | Quantitative | RCT | TB patients | Evaluation of effects of stigma intervention program | 155 intervention and 150 control participants |

| Mawey, 2023 [21] | Indonesia | Qualitative | Case-report | MDR TB patient and public | Reduction in workplace stigma and depression | 1 (case-report) |

| Moonsarn, 2023 [28] | Thailand | Quantitative | Quasi-experimental | Male high school students | Reduction in TB stigma and discrimination among high school students during COVID-19 | 216 students |

| Macdonald, 2024 [29] | Indonesia | Quantitative | Longitudinal intervention assessment | Trainers and TB patients and survivors | Reduction in TB self-stigma | 22 TB patients |

| Vibulchai, 2024 [30] | Thailand | Quantitative | One-group within-subjects repeated-measure design | Patients with TB | Reduction in internalized stigma among patients with TB | 26 TB patients |

| Author, Year | Stigma Type | Intervention Type and Components |

|---|---|---|

| Development of Stigma Interventions | ||

| Sabin, 2021 [19] | Perceived, enacted, and internalized stigma | To address enacted stigma, interventions incorporated celebrity advocacy and school-based educational programs aimed at raising community awareness shifting public perception of tuberculosis. Support groups and counseling were recommended to reduce internalized stigma among people living with TB. |

| Foster, 2024 [24] | Anticipated, internalized, and enacted stigma | Community-engaged, multi-level, multicomponent interventions with context-specific adaptations and survivor-led messaging. |

| Hayward, 2024 [22] | Internalized, anticipated, enacted, and intersectional stigma divided into individual, interpersonal, institutional, community, and policy levels of experiences | Individual-level interventions include digital platforms enabling TB survivor peer support with structured messaging and integrated healthcare provider counseling. Interpersonal approaches involve peer-led experience sharing and family-centered counseling. At the institutional level, training healthcare workers with survivor insights enhances understanding of patient experience, while restructuring service delivery prioritizes patient-centered care. Community-level efforts focus on increasing TB awareness through targeted education and outreach initiatives. At the policy level, action is needed to evaluate and address how existing policies perpetuate stigma in order to promote inclusive healthcare practices. |

| van der Westhuizen, 2024 [20] | Anticipated, internal, enacted, and intersectional stigma using Link and Phelan’s theoretical model and the Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework | At the individual level, tailored patient education should comprehensively explain tuberculosis infection prevention and control protocols. At the interpersonal level, healthcare providers should communicate IPC guidelines to patients using respectful, non-stigmatizing language and approaches. At the institutional level, healthcare facilities should reframe IPC measures as community safety practices rather than fear-driven responses to infection. Within communities, efforts should focus on creating environments that support voluntary status disclosure by reducing anxiety about unintentional exposure through visible IPC practices. At the policy level, reforms should promote the adoption of universal airborne precautions in high-risk settings, extending beyond TB-specific protocols, to mitigate stigma while maintaining protection. |

| Fuady, 2025 [25] | Internalized, enacted, and anticipated stigma | The study developed individualized psychological evaluations and counseling sessions; monthly peer-facilitated group counseling interventions; peer-delivered one-on-one psychosocial support; and community-centered educational sessions on TB, referred to as “TB Talks.” |

| Tuberculosis Treatment-Related Interventions with Demonstrated Impact on Stigma Reduction | ||

| Wilson, 2016 [23] | Anticipated and enacted stigma | The study developed a video-based TB education program comprising four key components: (1) general TB information, (2) TB screening and treatment protocols, (3) correction of common TB misconceptions, (4) authentic patient testimonials. |

| Taneja, 2017 [26] | Enacted stigma | The intervention comprised a home-based care system encompassing counseling, treatment adherence support, rehabilitative services, and nutritional assistance, delivered in conjunction with the standard pharmacological regimen. |

| Patel, 2020 [18] | Anticipated stigma | The study developed a human-centered redesign of the 99DOTS digital adherence technology, focusing on the pill packaging envelope displaying toll-free numbers for dose reporting and enhancing the overall patient experience with the system. |

| Stigma Reduction Interventions | ||

| Idris, 2020 [31] | Perceived, enacted, and internalized stigma assessed using the KAPS questionnaire | The intervention comprised a school-based TB education program for high school students that included a lecture on TB symptoms and treatment, a quiz, small group discussions to address local myths and community attitudes and practices related to TB transmission and knowledge, and a poster exhibition promoting an anti-smoking campaign. |

| Kara, 2022 [27] | Internalized, enacted, and anticipated stigma | The study implemented video directly observed therapy for TB patients with the following components: video observation, asynchronous or synchronous communication, patient education and training. |

| Faraade, 2023 [32] | Community and patient stigma assessed with 11 questions | The intervention comprised video and lecture programs on stigma for TB patients. |

| Mawey, 2023 [21] | Enacted stigma | The study implemented workplace psychosocial intervention on TB spread, and patient education and counseling. |

| Moonsarn, 2023 [28] | Enacted, internalized, anticipated, perceived and secondary stigma | The educational intervention comprises four sequential modules: TB prevention knowledge, stigma awareness training, stigma reduction through cognitive restructuring and empowerment techniques, and sustained information support systems. |

| Macdonald, 2024 [29] | Self-stigma | The study deployed an anti-self-stigma toolkit based on a socio-ecological model, comprising eight modules: (1) self-stigma introduction, (2) shame coping strategies, (3) DR-TB-specific impacts, (4) infection control contexts, (5) health rights linkages, (6) treatment-related stigma, (7) post-TB future planning, (8) stigma impact evaluation. |

| Vibulchai, 2024 [30] | Internalized stigma | The peer-delivered intervention incorporated four components: TB-specific health education, psychoeducation, self-management training, and community-based home visits. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aitambayeva, N.; Aringazina, A.; Nazarova, L.; Faizullina, K.; Bapayeva, M.; Narymbayeva, N.; Svetlanova, S. A Systematic Review of Tuberculosis Stigma Reduction Interventions. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151846

Aitambayeva N, Aringazina A, Nazarova L, Faizullina K, Bapayeva M, Narymbayeva N, Svetlanova S. A Systematic Review of Tuberculosis Stigma Reduction Interventions. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151846

Chicago/Turabian StyleAitambayeva, Nadira, Altyn Aringazina, Laila Nazarova, Kamila Faizullina, Magripa Bapayeva, Nazerke Narymbayeva, and Shnara Svetlanova. 2025. "A Systematic Review of Tuberculosis Stigma Reduction Interventions" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151846

APA StyleAitambayeva, N., Aringazina, A., Nazarova, L., Faizullina, K., Bapayeva, M., Narymbayeva, N., & Svetlanova, S. (2025). A Systematic Review of Tuberculosis Stigma Reduction Interventions. Healthcare, 13(15), 1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151846