Facing the Knife, Finding the Spirit? A Study of Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale (DSES) Scores in Romanian Surgical and Non-Surgical Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participant Selection

- Participants

- Surgical group (n = 51)

- Non-tumoral digestive pathology (n = 25): appendectomy (n = 15), cholecystectomy (n = 4), gastric ulcer surgery (n = 4), inguinal hernia surgery (n = 2);

- Benign gynecological tumors (n = 8): all underwent myomectomy;

- Oncological pathology (n = 7): breast cancer (n = 5), thyroid cancer (n = 1), colon cancer (n = 1);

- Benign urological pathology (n = 4): all with prostate adenoma;

- Other non-tumoral conditions (n = 7): ophthalmological (n = 2), cardiac (n = 2), orthopedic (n = 2), and neurosurgical (n = 1).

- Inclusion criteria (both groups):

- Age ≥ 18 years;

- Residence in the Bucovina region (Suceava County, Romania);

- For the surgical group: history of at least one surgical intervention;

- For the control group: no history of surgical or chronic medical conditions; self-reported good health.

- Exclusion criteria (both groups):

- Age under 18;

- Diagnosed psychiatric or neurological disorders;

- Terminal chronic illnesses;

- Any diagnosed mental health disorder.

2.2. Measures

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

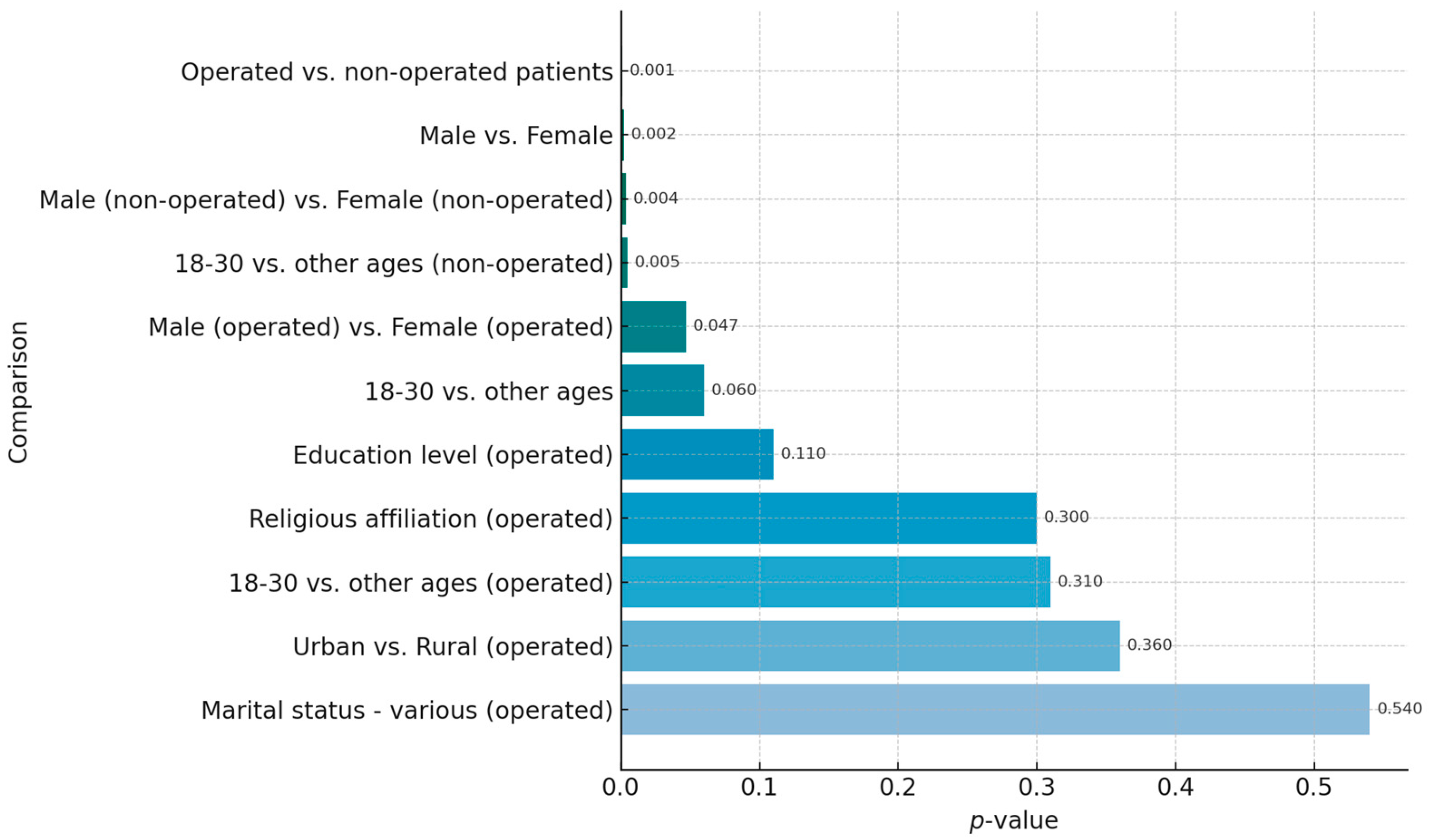

3.2. General Differences Between Operated and Non-Operated Patients

- Group Comparisons

- Sex Differences

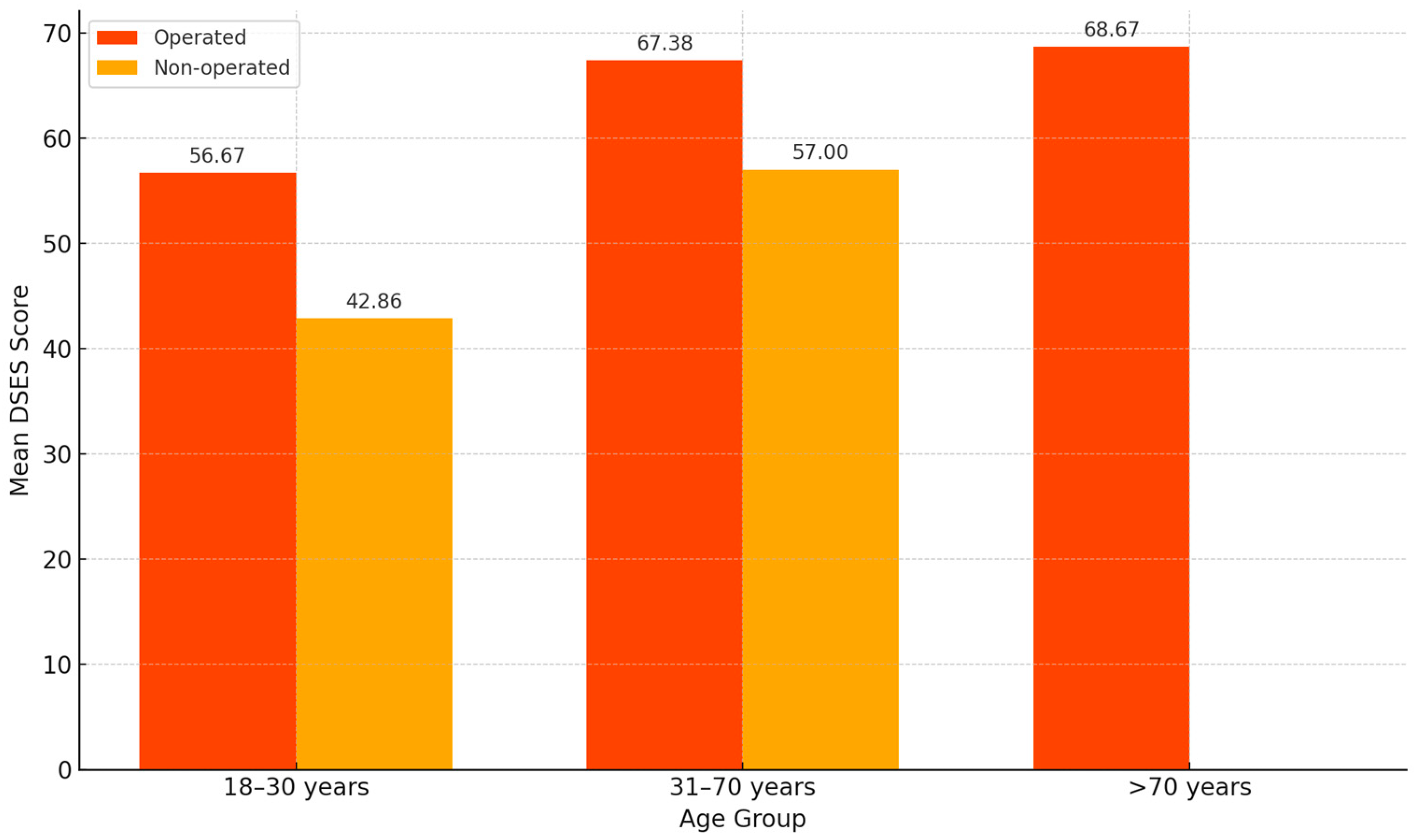

- Age-related Trends

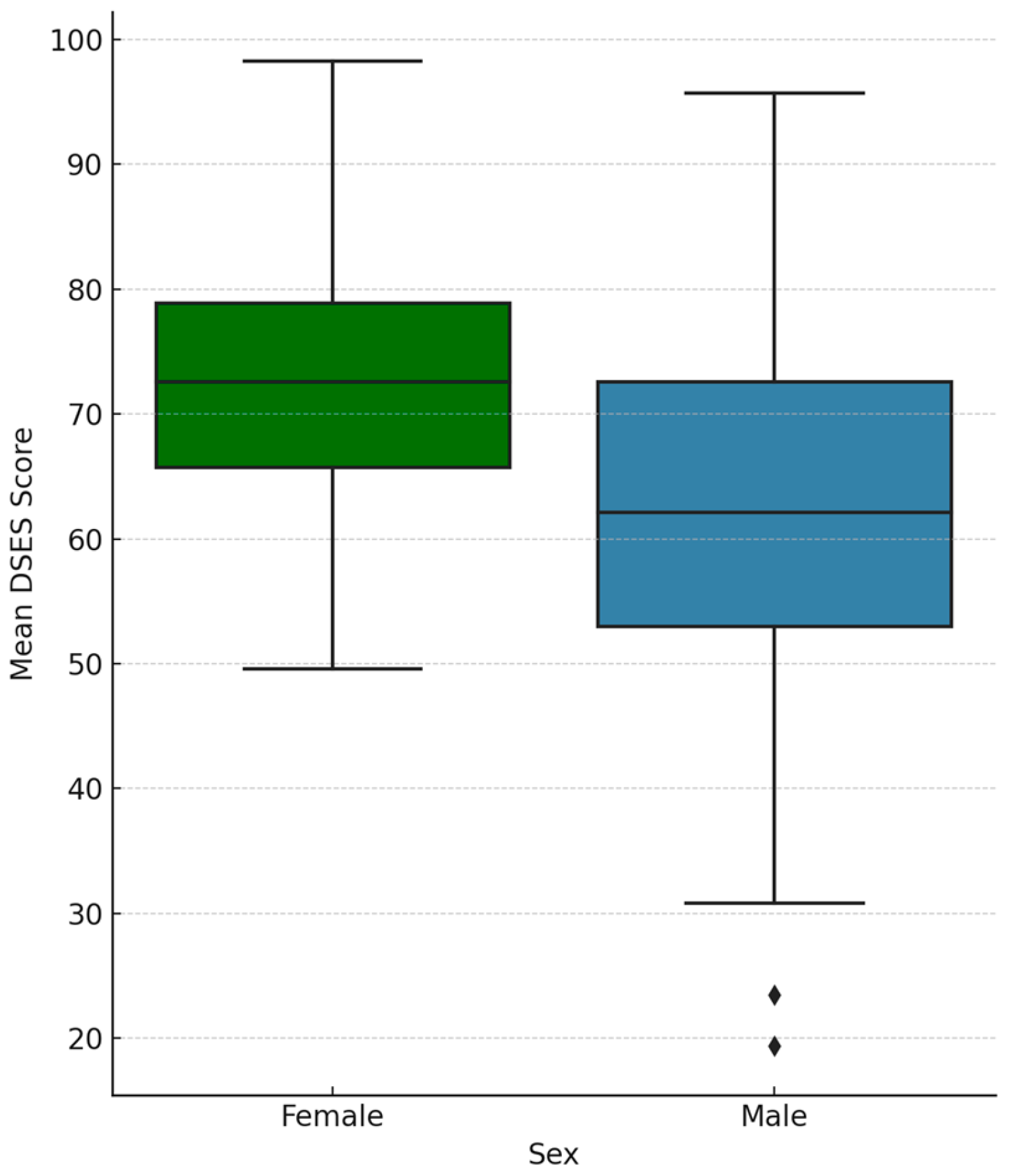

3.3. Female Gender as a Predictor of Increased Spirituality

3.4. Age-Related Trends in Spirituality Levels

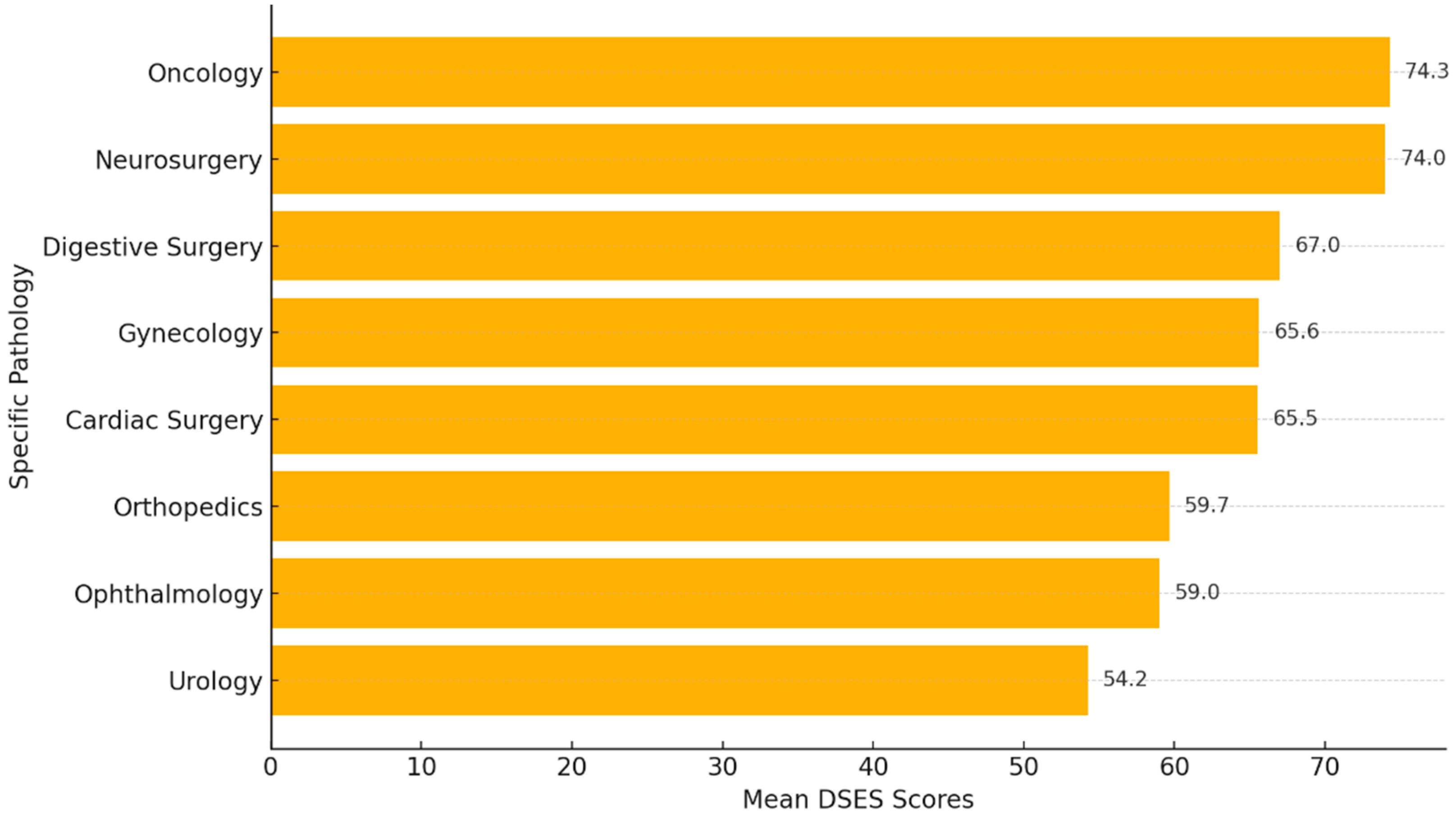

3.5. Correlation Between Spirituality Scores and Surgical Pathologies

3.6. Marital Status and DSES Score

3.7. Non-Significant Positive Association Between Education Level and Spirituality

3.8. Religious Affiliation and Level of Spirituality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-309-07280-9. [Google Scholar]

- Savel, R.H.; Munro, C.L. The Importance of Spirituality in Patient-Centered Care. Am. J. Crit. Care 2014, 23, 276–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merath, K.; Palmer Kelly, E.; Hyer, J.M.; Mehta, R.; Agne, J.L.; Deans, K.; Fischer, B.A.; Pawlik, T.M. Patient Perceptions About the Role of Religion and Spirituality During Cancer Care. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 1933–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucchetti, G.; Granero Lucchetti, A.L.; Peres, M.F.; Leão, F.C.; Moreira-Almeida, A.; Koenig, H.G. Validation of the Duke Religion Index: DUREL (Portuguese Version). J. Relig. Health 2012, 51, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchalski, C.M.; Vitillo, R.; Hull, S.K.; Reller, N. Improving the Spiritual Dimension of Whole Person Care: Reaching National and International Consensus. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 17, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oman, D. Defining Religion and Spirituality. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 2nd ed.; Paloutzian, R.F., Park, C.L., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Reutter, K.K.; Bigatti, S.M. Religiosity and Spirituality as Resiliency Resources: Moderation, Mediation, or Moderated Mediation? J. Sci. Study Relig. 2014, 53, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, A.; Shafranske, E.P. Envisioning an Integrative Paradigm for the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. In APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality, Volume 1: Context, Theory, and Research; Pargament, K.I., Exline, J.J., Jones, J.W., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer, B.J.; Pargament, K.I. Religiousness and Spirituality. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 1st ed.; Paloutzian, R.F., Park, C.L., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Salehi, M.; Hosseinigolafshani, S.Z.; Azimian, J.; Oveisi, S. Daily Spiritual Experience Level: Comparison between Healthy Adults and Hemodialysis Patients. Int. J. Novel Res. Healthc. Nurs. 2016, 3, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Yodchai, K.; Dunning, T.; Savage, S.; Hutchinson, A.M. The Role of Religion and Spirituality in Coping with Kidney Disease and Haemodialysis in Thailand. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2017, 31, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, A.; Balzat, H.J.; Heusser, P. Spiritual Needs of Patients with Chronic Pain Diseases and Cancer—Validation of the Spiritual Needs Questionnaire. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2010, 15, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, C.; Haley, W.E.; Balducci, L.; Extermann, M.; Perkins, E.A.; Small, B.J.; Mortimer, J. Impact of Breast Cancer Survivorship on Quality of Life in Older Women. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2007, 62, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarakeshwar, N.; Vanderwerker, L.C.; Paulk, E.; Pearce, M.J.; Kasl, S.V.; Prigerson, H.G. Religious Coping Is Associated with the Quality of Life of Patients with Advanced Cancer. J. Palliat. Med. 2006, 9, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, T.A.; Paulk, M.E.; Balboni, M.J.; Phelps, A.C.; Loggers, E.T.; Wright, A.A.; Block, S.D.; Lewis, E.F.; Peteet, J.R.; Prigerson, H.G. Provision of Spiritual Care to Patients with Advanced Cancer: Associations with Medical Care and Quality of Life near Death. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chester, D.N.; Himburg, S.P.; Weatherspoon, L.J. Spirituality of African-American Women: Correlations to Health-Promoting Behaviors. J. Natl. Black Nurses Assoc. 2006, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, Y.S.; Kim, D.H. Association between Religiosity/Spirituality and Quality of Life or Depression among Living-Alone Elderly in a South Korean City. Asia Pac. Psychiatry 2013, 5, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasiewicz, J.; Krzywoszański, Ł.; Prusak, J. Factor Structure of the Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale in a Polish-Christian Sample. Religions 2022, 13, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonelli, R.; Dew, R.E.; Koenig, H.G.; Rosmarin, D.H.; Vasegh, S. Religious and Spiritual Factors in Depression: Review and Integration of the Research. Depress. Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 962860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.W.; Reise, S.P.; Haviland, M.G. An Item Response Theory Analysis of the Spiritual Assessment Inventory. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 2007, 17, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, L.G. The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale: Overview and Results. Religions 2011, 2, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Underwood, L.G.; Teresi, J.A. The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale: Development, Theoretical Description, Reliability, Exploratory Factor Analysis, and Preliminary Construct Validity Using Health-Related Data. Ann. Behav. Med. 2002, 24, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrow, A.B.; Kwok, G.; Sharma, R.K.; Fromer, N.; Sulmasy, D.P. Spiritual Needs and Perception of Quality of Care and Satisfaction With Care in Hematology/Medical Oncology Patients: A Multicultural Assessment. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2018, 55, 56–64.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, A.C.; Lauderdale, K.E.; Alcorn, S.; Dillinger, J.; Balboni, M.T.; Van Wert, M.; Vanderweele, T.J.; Balboni, T.A. Addressing Spirituality within the Care of Patients at the End of Life: Perspectives of Patients with Advanced Cancer, Oncologists, and Oncology Nurses. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2538–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, K.I.; Koenig, H.G.; Tarakeshwar, N.; Hahn, J. Religious Coping Methods as Predictors of Psychological, Physical and Spiritual Outcomes among Medically Ill Elderly Patients: A Two-Year Longitudinal Study. J. Health Psychol. 2004, 9, 713–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, M.J.; Peterman, A.H.; Fitchett, G.; Mo, M.; Cella, D. A Case for Including Spirituality in Quality of Life Measurement in Oncology. Psychooncology 1999, 8, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairn, R.C.; Merluzzi, T.V. The Role of Religious Coping in Adjustment to Cancer. Psychooncology 2003, 12, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnoll, R.A.; Harlow, L.L.; Brower, L. Spirituality, Demographic and Disease Factors, and Adjustment to Cancer. Cancer Pract. 2000, 8, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.L.; Edmondson, D.; Hale-Smith, A.; Blank, T.O. Religiousness/Spirituality and Health Behaviors in Younger Adult Cancer Survivors: Does Faith Promote a Healthier Lifestyle? J. Behav. Med. 2009, 32, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, G.A.; Knittig, S.; Zoller, J.S.; Nietert, P.J. Importance of Faith on Medical Decisions Regarding Cancer Care. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 1379–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Psychosocial Services to Cancer Patients/Families in a Community Setting. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs; Adler, N.E., Page, A.E.K., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-309-11107-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, P.B.; Ransom, S. Implementation of NCCN Distress Management Guidelines by Member Institutions. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw. 2007, 5, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchalski, C.M. Spirituality in the Cancer Trajectory. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23 (Suppl. 3), 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistor, I. Istoria Bucovinei; Neagoe, S., Ed.; Humanitas: București, România, 1991; ISBN 973-28-0306-1. [Google Scholar]

- Vatamaniuc, D. Bucovina între Occident și Orient: Studii și documente; Ștefănescu, Ș., Ed.; Academiei Române: București, România, 2006; ISBN 973-27-1480-8. [Google Scholar]

- Cruceanu, A.D. Structura etno-lingvistică și confesională a populației Bucovinei în perioada interbelică (1918–1940). Analele Bucov. 2022, 58, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, I.G. Old and New Faith in Hungary, Turkish Hungary, and Transylvania. In A Companion to the Reformation World; Hsia, R.P.-C., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2006; Chapter 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pătrăucean, C.-A. Manifestări etno-folclorice ale grupurilor etnice din Bucovina între dinamism și conservare. An. Bucov. 2023, 61, 513–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institutul Național de Statistică. Recensământul Populației și Locuințelor, Runda 2021—Date Provizorii în Profil Teritorial. Available online: https://insse.ro/cms/ro/content/recens%C4%83m%C3%A2ntul-popula%C8%9Biei-%C8%99i-locuin%C8%9Belor-runda-2021-date-provizorii-%C3%AEn-profil-teritorial (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Suceava County Statistics Directorate. Statistical Yearbook of Suceava County 2023; Suceava County Statistics Directorate: Suceava, Romania, 2024; ISBN 978-606-94432-4-3. Available online: https://suceava.insse.ro/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Anuarul-Statistic-al-Judetului-Suceava-2023.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Underwood, L.G.; Vagnini, K.M. The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale: Empirical Relationships to Resiliency-Related Outcomes, Addictions, and Interventions. Religions 2022, 13, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, E.C.; Herța, D.C.; Cosman, D. Psychometrics Properties of the Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale in a Romanian Clinical Sample. A Pilot Study. J. Evid.-Based Psychother. 2022, 22, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakošec, Ž.; Mikšić, Š.; Juranić, B.; Batinić, L. Psychometric Characteristics of Croatian Version of the Daily Spiritual Experience Scale. Religions 2015, 6, 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkstein, S.; Tower, R.B. The Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale and Well-Being: Demographic Comparisons and Scale Validation with Older Jewish Adults and a Diverse Internet Sample. J. Relig. Health 2009, 48, 402–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pew Research Center. Religion in America: U.S. Religious Data, Demographics and Statistics. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/collections/religious-landscape-study/ (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Kelly, E.P.; Pawlik, T.M. ASO Author Reflections: Influence of Patient Clinical- and Treatment-Level Factors on Religious/Spiritual Preferences During Cancer Care. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 27, 753–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, H.G. Spiritual Aspects of Surgery. Ophthalmol. Clin. N. Am. 2000, 13, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irsay, L.; Ciortea, V.M.; Popa, T.; Iliescu, M.G.; Ciubean, A.D. Exploring the Connections between Medical Rehabilitation, Faith and Spirituality. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoviciu, S.; Birle, D.; Olah, S.; Popoviciu, I. The Role of Religious Beliefs and Spirituality on the Quality of Life of Rare Diseases Patients. Rev. Cercet. Interv. Soc. 2012, 36, 144–161. [Google Scholar]

- Frent, S.; Popovici, A.-F.; Balan, A.; Cerbu, B.; Marincu, I.; Mihaicuta, S.; Bikov, A. Religiosity and Health Outcomes in a Cohort of Romanian Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19. J. Relig. Health 2025, 64, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, A.; Park, C.L.; Shearer, M. Pastoral Abstracts. J. Pastor. Care Couns. 2010, 64, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karačić, A.; Brkić, J.; Theunissen, M.; Sović, S.; Karimollahi, M.; Bakula, B.; Karačić, J.; Rosmarin, D.H. Are Religious Patients Less Afraid of Surgery? A Cross-Sectional Study on the Relationship between Dimensions of Religiousness and Surgical Fear. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woll, M.L.; Hinshaw, D.B.; Pawlik, T.M. Spirituality and Religion in the Care of Surgical Oncology Patients with Life-Threatening or Advanced Illnesses. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2008, 15, 3048–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, A.J.; Flannelly, K.J. The Role of Religion/Spirituality for Cancer Patients and Their Caregivers. South. Med. J. 2004, 97, 1210–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitford, H.S.; Olver, I.N.; Peterson, M.J. Spirituality as a Core Domain in the Assessment of Quality of Life in Oncology. Psychooncology 2008, 17, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Wellisch, D.K.; Spillers, R.L.; Crammer, C. Psychological Distress of Female Cancer Caregivers: Effects of Type of Cancer and Caregivers’ Spirituality. Support. Care Cancer 2007, 15, 1367–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammermeister, J.; Flint, M.; El-Alayli, A.; Ridnour, H.; Peterson, M. Gender Differences in Spiritual Well-Being: Are Females More Spiritually-Well than Males? Am. J. Health Stud. 2005, 20, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, A.N. Gender Differences in Spiritual Development during the College Years. Sex. Roles 2007, 56, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galek, K.; Flannelly, K.J.; Jacobs, M.R.; Barone, J.D. Spiritual Needs: Gender Differences among Professional Spiritual Care Providers. J. Pastor. Care Couns. 2008, 62, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasdeu, I. Dieu au quotidien. Esquisse d’une anthropologie de la spiritualité féminine. Études Théol. Relig. 2004, 79, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, J.; Tarpley, M.J.; Haaz, S.; Bartlett, S.J. Daily Spiritual Experiences of Older Adults with and without Arthritis and the Relationship to Health Outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 59, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Nezlek, J.B. Whether, When, and How Is Spirituality Related to Well-Being? Moving beyond Single Occasion Questionnaires to Understanding Daily Process. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 38, 1523–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Chadha, N.K. Spirituality: Investigating the Effects of Age and Gender. Indian. J. Posit. Psychol. 2013, 4, 478–485. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, J. Spiritual Development in Later Life: A Learning Experience. In Spiritual Dimensions of Ageing; Walker, J., Johnson, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 249–269. ISBN 978-1-107-46584-8. [Google Scholar]

- Atchley, R.C. How Spiritual Experience and Development Interact with Aging. J. Transpers. Psychol. 2011, 43, 156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Lavretsky, H. Spirituality and Aging. Aging Health 2010, 6, 749–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalby, P. Is There a Process of Spiritual Change or Development Associated with Ageing? A Critical Review of Research. Aging Ment. Health 2006, 10, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, T.A.; Acree, M.; Folkman, S. Spiritual Aspects of Loss among Partners of Men with AIDS: Postbereavement Follow-Up. Death Stud. 1999, 23, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, M.; Marquez-Wong, F.; Simon, G.B.; Kira, H.; Becker, C. Bereavement Life Review Improves Spiritual Well-Being and Ameliorates Depression among American Caregivers. Palliat. Support. Care 2015, 13, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, M.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Shiihara, Y.; Izuhara, K. Universality of Bereavement Life Review for Spirituality and Depression in Bereaved Families. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2014, 31, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonanda, I.; Nuryoto, S.; Urbayatun, S. Personal Growth in Women After Husband’s Death. Psikostudia 2022, 11, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, T.B.; de Oliveira, M.P.; da Silva Melo, C. A espiritualidade nos cuidados de enfermagem ao paciente oncológico: Uma revisão narrativa. Rev. Eletrônica Cient. Saúde 2021, 9, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Liou, S.-H.; Chen, C.-H. Spiritual Care in Nursing Practice. Hu Li Za Zhi 2008, 55, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soheili, M.; Mollai Iveli, M. A Review of the Role of Spiritual Cares in the Nursing Profession. J. Relig. Health 2019, 7, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira, S.; Narayanasamy, A. Programas de educação em enfermagem acerca da espiritualidade: Uma revisão sistemática. Cuid. Enferm. 2011, 5, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

| Variable Subgroup | Operated Patients | Non-Operated Patients | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (Mean ± SD) | N | (N, Mean ± SD) | |||

| Gender | Female | 26 | 70.73 ± 13.1 | 27 | 59.85 ± 11.34 | 0.004 ** |

| Male | 25 | 61.64 ± 18.36 | 24 | 49.67 ± 12.41 | 0.047 * | |

| Age group (years) | 18–30 | 6 | 56.67 ± 27.38 | 7 | 42.86 ± 14.31 | 0.005 ** |

| 31–70 | 39 | 67.38 ± 13.54 | 44 | 57.00 ± 11.58 | — | |

| ≥71 | 6 | 68.67 ± 20.47 | - | — | — | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cucu, A.I.; Turliuc, Ş.; Sandiuc, M.C.; Dascălu, C.G.; Boişteanu, O.; Bobu, A.M.; Costea, C.F.; Prutianu, I.; Cărăuleanu, A.; Buzdugă, C.M.; et al. Facing the Knife, Finding the Spirit? A Study of Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale (DSES) Scores in Romanian Surgical and Non-Surgical Patients. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1820. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151820

Cucu AI, Turliuc Ş, Sandiuc MC, Dascălu CG, Boişteanu O, Bobu AM, Costea CF, Prutianu I, Cărăuleanu A, Buzdugă CM, et al. Facing the Knife, Finding the Spirit? A Study of Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale (DSES) Scores in Romanian Surgical and Non-Surgical Patients. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1820. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151820

Chicago/Turabian StyleCucu, Andrei Ionut, Şerban Turliuc, Mihaela Cristina Sandiuc (Pietsch), Cristina Gena Dascălu, Otilia Boişteanu, Amelian Mădălin Bobu, Claudia Florida Costea, Iulian Prutianu, Alexandru Cărăuleanu, Catalin Mihai Buzdugă, and et al. 2025. "Facing the Knife, Finding the Spirit? A Study of Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale (DSES) Scores in Romanian Surgical and Non-Surgical Patients" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1820. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151820

APA StyleCucu, A. I., Turliuc, Ş., Sandiuc, M. C., Dascălu, C. G., Boişteanu, O., Bobu, A. M., Costea, C. F., Prutianu, I., Cărăuleanu, A., Buzdugă, C. M., Covali, R., Tamaş, C., Hristea, A., & Pătrăşcanu, E. (2025). Facing the Knife, Finding the Spirit? A Study of Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale (DSES) Scores in Romanian Surgical and Non-Surgical Patients. Healthcare, 13(15), 1820. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151820