Patterns of Distress and Supportive Resource Use by Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Measures

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

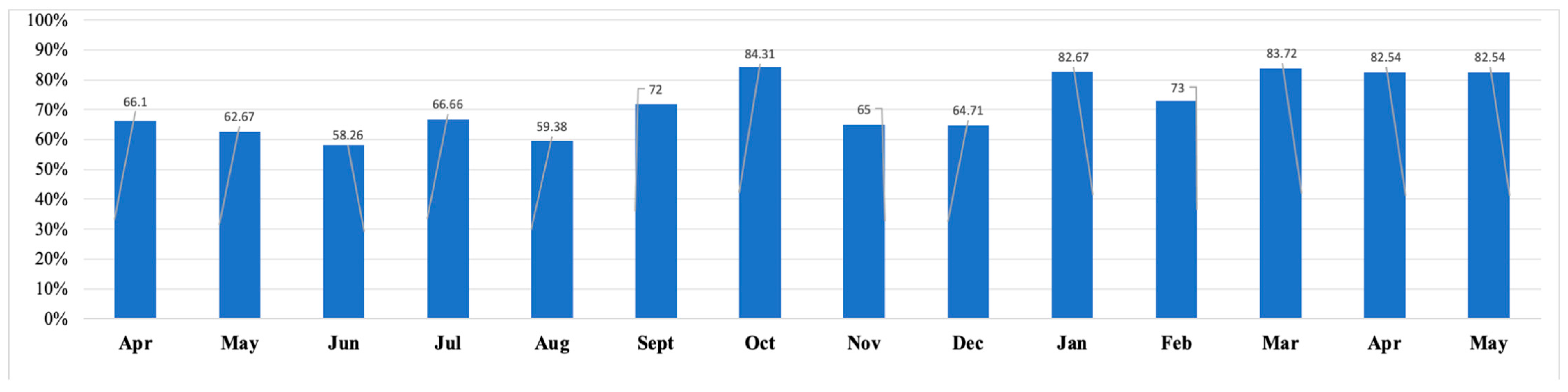

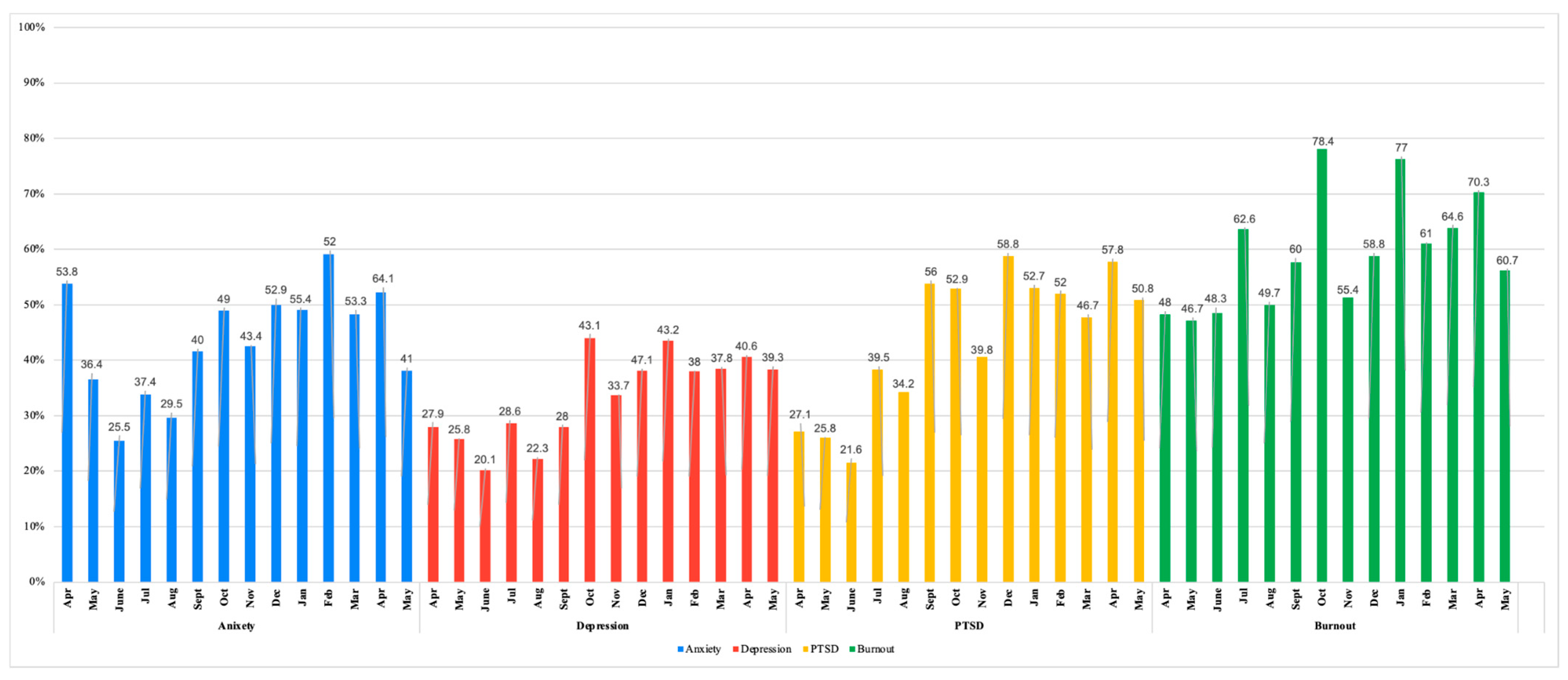

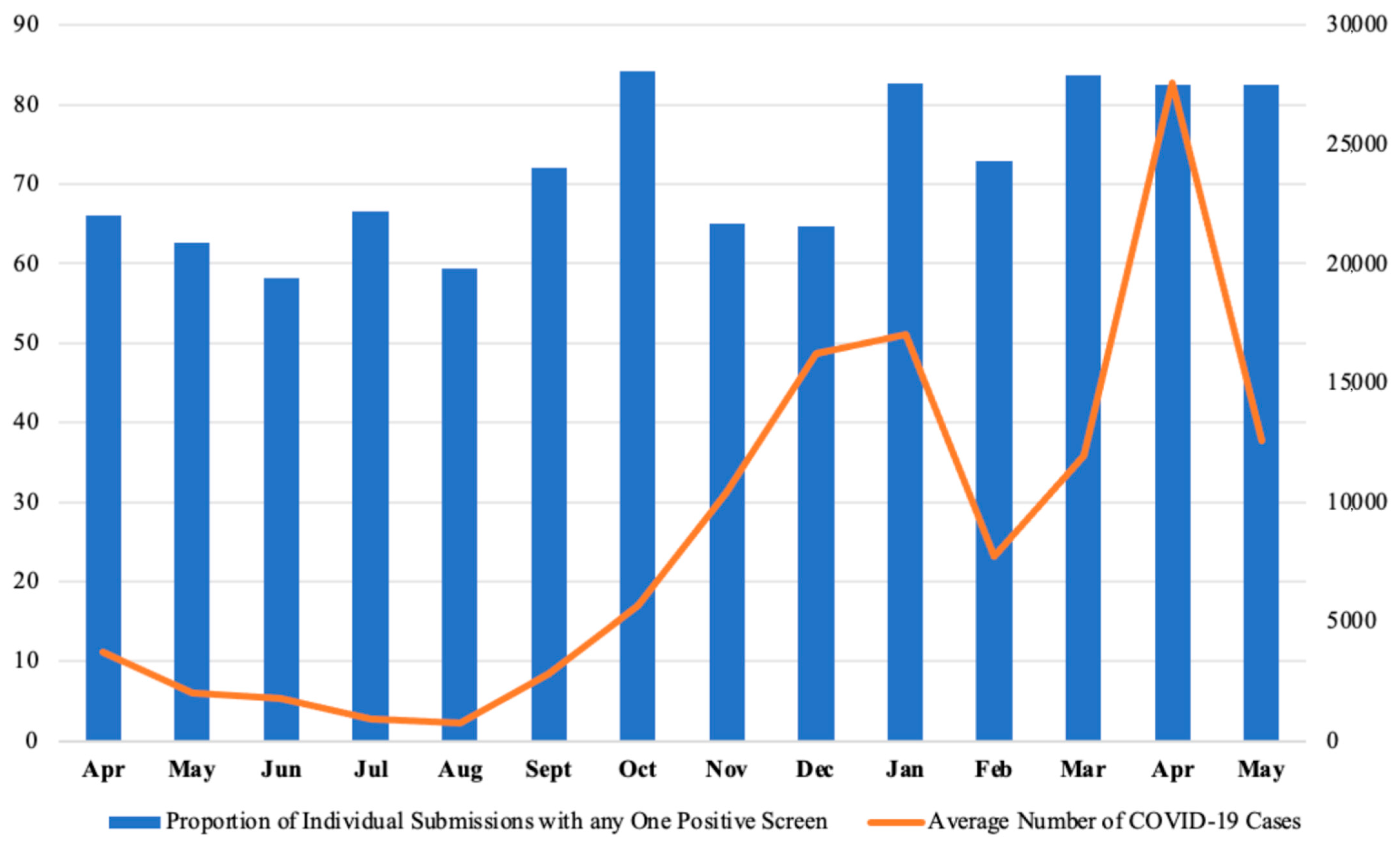

3.2. Trends of Psychological Distress

4. Discussion

4.1. First COVID-19 Government-Mandated Lockdown

4.2. Lifting of First Government-Mandated Lockdowns

4.3. Second Wave (The Beta Variant)

4.4. Prolonged Impact of the COVID-19 Third Wave on Healthcare Worker Distress

- Mental Health Support Access

- Occupational Stress and Support Interventions

4.5. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

4.6. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Month | Resource | n | % of Monthly Respondents |

|---|---|---|---|

| April 2020 (n = 848) | Online | 199 | 23.5 |

| EAP | 21 | 2.5 | |

| Professional | 47 | 5.5 | |

| One on One | - | - | |

| Group | - | - | |

| Lavender Alert | - | - | |

| Family/Friends | - | - | |

| Colleagues | - | - | |

| None | 518 | 61.1 | |

| Other | 133 | 15.7 | |

| May 2020 (n = 332) | Online | 71 | 21.4 |

| EAP | 10 | 3.0 | |

| Professional | 34 | 10.2 | |

| One on One | - | - | |

| Group | - | - | |

| Lavender Alert | - | - | |

| Family/Friends | - | - | |

| Colleagues | - | - | |

| None | 191 | 57.5 | |

| Other | 45 | 13.6 | |

| June 2020 (n = 291) | Online | 72 | 24.7 |

| EAP | 6 | 2.1 | |

| Professional | 27 | 9.3 | |

| One on One | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Group | 10 | 3.4 | |

| Lavender Alert | 5 | 1.7 | |

| Family/Friends | 188 | 64.6 | |

| Colleagues | 121 | 41.6 | |

| None | 76 | 26.1 | |

| Other | 20 | 6.9 | |

| July 2020 (n = 127) | Online | 28 | 22.1 |

| EAP | 9 | 7.1 | |

| Professional | 14 | 11.0 | |

| One on One | 3 | 2.4 | |

| Group | 6 | 4.7 | |

| Lavender Alert | 1 | 0.8 | |

| Family/Friends | 76 | 59.8 | |

| Colleagues | 51 | 40.2 | |

| None | 34 | 26.8 | |

| Other | 5 | 3.9 | |

| August 2020 (n = 175) | Online | 39 | 22.3 |

| EAP | 10 | 5.7 | |

| Professional | 16 | 9.1 | |

| One on One | 4 | 2.3 | |

| Group | 14 | 8.0 | |

| Lavender Alert | 3 | 1.7 | |

| Family/Friends | 108 | 61.7 | |

| Colleagues | 58 | 33.1 | |

| None | 42 | 24.0 | |

| Other | 11 | 6.29 | |

| September 2020 (n = 22) | Online | 6 | 27.3 |

| EAP | - | - | |

| Professional | 6 | 27.3 | |

| One on One | 1 | 4.5 | |

| Group | 3 | 13.6 | |

| Lavender Alert | - | - | |

| Family/Friends | 15 | 68.2 | |

| Colleagues | 13 | 59.1 | |

| None | 5 | 22.7 | |

| Other | 5 | 22.7 | |

| October 2020 (n = 46) | Online | 11 | 23.9 |

| EAP | 5 | 10.9 | |

| Professional | 10 | 21.7 | |

| One on One | 3 | 6.5 | |

| Group | 2 | 4.4 | |

| Lavender Alert | - | - | |

| Family/Friends | 37 | 80.4 | |

| Colleagues | 22 | 47.8 | |

| None | 6 | 13.0 | |

| Other | 5 | 10.9 | |

| November 2020 (n = 76) | Online | 21 | 27.6 |

| EAP | 6 | 7.9 | |

| Professional | 18 | 23.7 | |

| One on One | 3 | 4.0 | |

| Group | 4 | 5.3 | |

| Lavender Alert | - | - | |

| Family/Friends | 54 | 71.1 | |

| Colleagues | 33 | 43.0 | |

| None | 14 | 18.4 | |

| Other | 12 | 15.8 | |

| December 2020 (n = 14) | Online | 6 | 42.9 |

| EAP | 2 | 14.3 | |

| Professional | 3 | 21.4 | |

| One on One | - | - | |

| Group | 2 | 14.3 | |

| Lavender Alert | - | - | |

| Family/Friends | 12 | 85.7 | |

| Colleagues | 7 | 50.0 | |

| None | - | - | |

| Other | 3 | 21.4 | |

| January 2021 (n = 68) | Online | 18 | 26.5 |

| EAP | 9 | 13.2 | |

| Professional | 13 | 19.1 | |

| One on One | 3 | 4.4 | |

| Group | 2 | 2.9 | |

| Lavender Alert | - | - | |

| Family/Friends | 44 | 64.7 | |

| Colleagues | 33 | 48.5 | |

| None | 15 | 22.1 | |

| Other | 10 | 14.7 | |

| February 2021 (n = 90) | Online | 17 | 18.9 |

| EAP | 10 | 11.1 | |

| Professional | 10 | 11.1 | |

| One on One | 1 | 1.1 | |

| Group | 7 | 7.8 | |

| Lavender Alert | 5 | 5.6 | |

| Family/Friends | 57 | 63.3 | |

| Colleagues | 35 | 38.9 | |

| None | 19 | 21.1 | |

| Other | 10 | 11.1 | |

| March 2021 (n = 40) | Online | 14 | 35.0 |

| EAP | 5 | 12.5 | |

| Professional | 8 | 20.0 | |

| One on One | 3 | 7.5 | |

| Group | 3 | 7.5 | |

| Lavender Alert | - | - | |

| Family/Friends | 24 | 60.0 | |

| Colleagues | 16 | 40.0 | |

| None | 7 | 17.5 | |

| Other | 1 | 2.5 | |

| April 2021 (n = 56) | Online | 14 | 25.0 |

| EAP | 6 | 10.7 | |

| Professional | 10 | 17.9 | |

| One on One | 3 | 5.4 | |

| Group | 30 | 53.6 | |

| Lavender Alert | - | - | |

| Family/Friends | 4 | 7.1 | |

| Colleagues | 16 | 28.6 | |

| None | 14 | 25.0 | |

| Other | 7 | 12.5 | |

| May 2021 (n = 53) | Online | 16 | 30.2 |

| EAP | 4 | 7.6 | |

| Professional | 12 | 22.6 | |

| One on One | 4 | 7.5 | |

| Group | 7 | 13.2 | |

| Lavender Alert | - | - | |

| Family/Friends | 34 | 64.2 | |

| Colleagues | 17 | 32.1 | |

| None | 7 | 13.2 | |

| Other | 5 | 9.4 |

References

- Raišienė, A.G.; Danauskė, E.; Kavaliauskienė, K.; Gudžinskienė, V. Occupational stress-induced consequences to employees in the context of teleworking from home: A preliminary study. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, K.; Modi, B.; Singhal, S.; Gupta, S. Occupational stress among health care workers. In Identifying Occupational Stress and Coping Strategies; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, J.; Ku, M.; Wang, H.; Crosse, K.; Bennett, A.; Lee, E.; Simmons, A.; Duffy, L.; Montanaro, K.; Bazaid, K. Public health emergency and psychological distress among healthcare workers: A scoping review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirico, F.; Ferrari, G.; Nucera, G.; Szarpak, L.; Crescenzo, P.; Ilesanmi, O. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, burnout syndrome, and mental health disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid umbrella review of systematic reviews. J. Health Soc. Sci. 2021, 6, 209–220. [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt, T.; Ripp, J.; Trockel, M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA 2020, 323, 2133–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisely, S.; Warren, N.; McMahon, L.; Dalais, C.; Henry, I.; Siskind, D. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: Rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020, 369, m1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Burnout. In Stress: Concepts, Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 351–357. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelnicki, A.M.; Jamshidi, L.; Angehrn, A.; Hadjistavropoulos, H.D.; Carleton, R.N. Associations between burnout and mental disorder symptoms among nurses in Canada. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 53, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberque, B.; Laporte, C.; Mondillon, L.; Baker, J.S.; Mermillod, M.; Brousse, G.; Ugbolube, U.C.; Bagheri, R.; Bouillon-Minois, J.B.; Dutheil, F. Prevalence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in healthcare workers following the first SARS-CoV epidemic of 2003: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelnicki, A.M.; Jamshidi, L.; Ricciardelli, R.; Carleton, R.N. Exposures to potentially psychologically traumatic events among nurses in Canada. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 53, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, I.M.; Moretti, F.; Mazzi, M.; Wu, A.W.; Rimondini, M. What we have learned from two decades of epidemics and pandemics: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychological burden of frontline healthcare workers. Psychother. Psychosom. 2021, 90, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahebi, A.; Nejati-Zarnaqi, B.; Moayedi, S.; Yousefi, K.; Torres, M.; Golitaleb, M. The prevalence of anxiety and depression among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 107, 110247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binnie, A.; Moura, K.; Moura, C.; D’Aragon, F.; Tsang, J.L.Y. Psychosocial distress amongst Canadian intensive care unit healthcare workers during the acceleration phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S.; Dimitropoulos, G.; Williams, J.V.; Sharifi, V.; Fahim, M.; Munir, A.; Bullock, A.G.M.; Patten, S.B. Associations between negative COVID-19 experiences and symptoms of anxiety and depression: A study based on a representative Canadian national sample. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2024, 44, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, S.R.; Li, J.; Marsh, S.M.; Carbone, E.G. Prepandemic mental health and well-being: Differences within the health care workforce and the need for targeted resources. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2022, 64, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeosun, A.O. Exploring the Stressors and Coping Experiences of Healthcare Workers in Long-Term Care Homes During COVID-19 Crisis Within Southern Alberta. Master’s Thesis, University of Lethbridge, Lethbridge, AB, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ladha, P.; Lasinski, A.M.; Kara, A.M.; Relation, T.; Tseng, E.S. Burnout in trauma surgeons during the COVID-19 pandemic: A long-standing problem worsens. Curr. Trauma Rep. 2023, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knaak, S.; Mantler, E.; Szeto, A. Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare: Barriers to access and care and evidence-based solutions. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2017, 30, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, E.; DePierro, J.M.; Marin, D.B.; Sharma, V.; Charney, D.S.; Katz, C.L. COVID-19 pandemic support programs for healthcare workers and implications for occupational mental health: A narrative review. Psychiatr. Q. 2021, 93, 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simms, L.; Ottman, K.E.; Griffith, J.L.; Knight, M.G.; Norris, L.; Karakcheyeva, V.; Kohrt, B.A. Psychosocial peer support to address mental health and burnout of health care workers affected by COVID-19: A qualitative evaluation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spoorthy, M.S.; Pratapa, S.K.; Mahant, S. Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic—A review. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, J.; Korman, M.B. Development of an evidence-informed solution to emotional distress in public safety personnel and healthcare workers: The social support, tracking distress, education, and discussion communitY (STEADY) program. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worley, J.A.; Vassar, M.; Wheeler, D.L.; Barnes, L.L. Factor structure of scores from the Maslach Burnout Inventory: A review and meta-analysis of 45 exploratory and confirmatory factor-analytic studies. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2008, 68, 797–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.; Monahan, P.O.; Löwe, B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 146, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, A.J.; Dunn, K.M.; Chaffee, T.; Bhattarai, J.J.; Beier, M. Diagnostic and clinical utility of the GAD-2 for screening anxiety symptoms in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 2045–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Med. Care 2003, 41, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prins, A.; Bovin, M.J.; Smolenski, D.J.; Marx, B.P.; Kimerling, R.; Jenkins-Guarnieri, M.A.; Kaloupek, D.G.; Schnurr, P.P.; Kaiser, A.P.; Leyva, Y.E.; et al. The Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): Development and evaluation within a Veteran primary care sample. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2016, 31, 1206–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, A.J.; Stein, M.B. An abbreviated PTSD checklist for use as a screening instrument in primary care. Behav. Res. Ther. 2005, 43, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weathers, F.W.; Litz, B.; Herman, D.; Juska, J.; Keane, T. PTSD Checklist—Civilian Version (PCL-C) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavender Alert Guide. Available online: https://www.ppno.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/2019.08.22-Lavender-Alert-Guide-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- IBM. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 29.0.1.0, IBM Corporation: Armonk, NY, USA, 2023.

- Boucher, V.G.; Dahl, M.; Lee, J.; Faulkner, G.; Beauchamp, M.R.; Puterman, E. An umbrella review and meta-analysis of 87 meta-analyses examining healthcare workers’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 375, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Ontario. Emergency Management and Civil Protection Act: Stay-at-Home Order. Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2020. Government of Canada; Road to Mental Readiness; Department of National Defence. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/services/benefits-military/health-support/road-to-mental-readiness.html (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Tuite, A.R.; Fisman, D.N.; Greer, A.L. Mathematical modelling of COVID-19 transmission and mitigation strategies in the population of Ontario, Canada. CMAJ 2020, 192, E497–E505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, I.H.C.; Bathje, G.J.; Kalibatseva, Z.; Sung, D.H.; Leong, F.T.L.; Collins-Eaglin, J. Stigma, mental health, and counseling service use: A person-centered approach to mental health stigma profiles. Psychol. Serv. 2017, 14, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Clark, D.A. Anxiety and depression: An information processing perspective. Anxiety Res. 1997, 1, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunder, R.G.; Lancee, W.J.; Rourke, S.; Hunter, J.J.; Goldbloom, D.; Balderson, K.; Petryshen, P.; Steinberg, R.; Wasylenki, D.; Koh, D.; et al. Factors associated with the psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on nurses and other hospital workers in Toronto. Psychosom. Med. 2004, 66, 938–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirois, F.M.; Owens, J. Factors associated with psychological distress in health-care workers during an infectious disease outbreak: A rapid systematic review of the evidence. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 589545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maunder, R.G.; Lancee, W.J.; Balderson, K.E.; Bennett, J.P.; Borgundvaag, B.; Evans, S.; Fernandes, C.M.; Goldbloom, D.S.; Gupta, M.; Hunter, J.J.; et al. Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 1924–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chum, A.; Nielsen, A.; Bellows, Z.; Farrell, E.; Durette, P.N.; Banda, J.M.; Cupchik, G. Changes in public response associated with various COVID-19 restrictions in Ontario, Canada: Observational infoveillance study using social media time series data. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e28716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.; Mougouei, D.; Evans, S.L. Understanding the emotional response to COVID-19 information in news and social media: A mental health perspective. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 3, 832–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amodio, E.; Battisti, M.; Kourtellos, A.; Maggio, G.; Maida, C.M. Schools opening and COVID-19 diffusion: Evidence from geolocalized microdata. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2022, 143, 104003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, S.A.; Saliba, V.; Lopez Bernal, J.; Ramsay, M.E.; Ladhani, S.N. SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission in educational settings: A prospective, cross-sectional analysis of infection clusters and outbreaks in England. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dale, L.P.; Cuffe, S.P.; Sambuco, N.; Guastello, A.D.; Leon, K.G.; Nunez, L.V.; Bhullar, A.; Allen, B.R.; Mathews, C.A. Morally Distressing Experiences, Moral Injury, and Burnout in Florida Healthcare Providers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansone, R.A.; Sansone, L.A. The christmas effect on psychopathology. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 8, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Public Health Ontario. Respiratory virus tool. Public Health Ontario. Available online: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/data-and-analysis/infectious-disease/respiratory-virus-tool (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Hennein, R.; Lowe, S. A hybrid inductive-abductive analysis of health workers’ experiences and wellbeing during COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holgate, S.; Bird, W.; Boyle, A.; Butler, C.; Sigfrid, L. COVID-19: Preparing for the Future: Looking Ahead to Winter 2021/22 and Beyond. 2021. Available online: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:76d3706c-fba0-47ab-b5d5-cde691997f27 (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- Carolan, S.; Harris, P.R.; Cavanagh, K. Improving employee well-being and effectiveness: Systematic review and meta-analysis of web-based psychological interventions delivered in the workplace. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewey, C.; Hingle, S.; Goelz, E.; Linzer, M. Supporting clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 172, 752–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, D.L.; Heimerdinger-Edwards, S.R.; Hammer, J.H.; Hubbard, A. “Boys don’t cry”: Examination of the links between endorsement of masculine norms, self-stigma, and help-seeking attitudes for men from diverse backgrounds. J. Counsel. Psychol. 2014, 58, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidler, Z.E.; Dawes, A.J.; Rice, S.M.; Oliffe, J.L.; Dhillon, H.M. The role of masculinity in men’s help-seeking for depression: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 49, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidler, Z.E.; Rice, S.M.; Kealy, D.; Oliffe, J.L.; Ogrodniczuk, J.S. What gets in the way? Men’s perspectives of barriers to mental health services. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranasinghe, P.D. Women physicians and the COVID-19 pandemic: Gender-based impacts and potential interventions. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatmon, B.N. Males and mental health stigma. Am. J. Mens Health 2020, 14, 1557988320949322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, D.L.; Heath, P.J. Men, masculinities, and help-seeking patterns. In APA Handbook of Men and Masculinities; Wong, Y.J., Wester, S.R., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 685–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, B.P.; Ingram, P.B. Where do I turn for help? Gender role conflict, self-stigma, and college men’s help-seeking for depression. Psychol. Men Masculinities 2020, 21, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.; Michail, M.; Callaghan, P. The role of peer support in enhancing mental health services. Ment. Health Prev. 2018, 10, 24–36. [Google Scholar]

| Demographic Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Woman | 585 | 84.97 |

| Man | 94 | 13.66 |

| Nonbinary | 3 | 0.44 |

| Questioning | 1 | 0.15 |

| Prefer not to say | 5 | 0.73 |

| Age Range | ||

| Under 19 | 1 | 0.12 |

| 20–29 | 153 | 18.23 |

| 30–39 | 228 | 27.19 |

| 40–49 | 195 | 23.25 |

| 50–59 | 180 | 21.44 |

| 60–69 | 47 | 5.60 |

| 70+ | 2 | 0.24 |

| Responded but did not specify | 33 | 3.93 |

| Month | Screens | M | SD | n Positive Screens |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 2020 (n = 945) | Anxiety | 3.04 | 2.04 | 508 |

| Depression | 1.79 | 1.85 | 264 | |

| PTSD | 1.59 | 1.57 | 256 | |

| Burnout | 2.61 | 1.00 | 454 | |

| May 2020 (n = 368) | Anxiety | 2.28 | 1.88 | 134 |

| Depression | 1.79 | 1.67 | 95 | |

| PTSD | 1.49 | 1.59 | 95 | |

| Burnout | 2.57 | 1.02 | 172 | |

| June 2020 (n = 329) | Anxiety | 1.83 | 1.85 | 84 |

| Depression | 1.47 | 1.58 | 66 | |

| PTSD | 1.22 | 1.54 | 71 | |

| Burnout | 2.60 | 1.05 | 159 | |

| July 2020 (n = 147) | Anxiety | 2.23 | 1.81 | 55 |

| Depression | 1.71 | 1.72 | 42 | |

| PTSD | 13.31 | 5.89 | 58 | |

| Burnout | 2.92 | 1.02 | 92 | |

| August 2020 (n = 193) | Anxiety | 1.94 | 1.74 | 57 |

| Depression | 1.58 | 1.66 | 43 | |

| PTSD | 12.31 | 5.91 | 66 | |

| Burnout | 2.63 | 1.14 | 96 | |

| September 2020 (n = 25) | Anxiety | 2.36 | 1.55 | 10 |

| Depression | 1.60 | 1.41 | 7 | |

| PTSD | 13.83 | 4.86 | 14 | |

| Burnout | 2.60 | 0.87 | 15 | |

| October 2020 (n = 51) | Anxiety | 2.90 | 1.91 | 25 |

| Depression | 2.53 | 1.99 | 22 | |

| PTSD | 14.92 | 5.93 | 27 | |

| Burnout | 3.22 | 0.95 | 40 | |

| November 2020 (n = 47) | Anxiety | 2.63 | 1.85 | 36 |

| Depression | 2.01 | 1.83 | 28 | |

| PTSD | 13.65 | 6.10 | 33 | |

| Burnout | 2.89 | 1.08 | 46 | |

| December 2020 (n = 17) | Anxiety | 3.12 | 2.0 | 9 |

| Depression | 2.59 | 1.58 | 8 | |

| PTSD | 16.18 | 6.78 | 10 | |

| Burnout | 2.94 | 1.25 | 10 | |

| January 2021 (n = 74) | Anxiety | 3.34 | 2.15 | 41 |

| Depression | 2.58 | 1.85 | 32 | |

| PTSD | 15.04 | 6.10 | 39 | |

| Burnout | 3.36 | 1.18 | 57 | |

| February 2021 (n = 100) | Anxiety | 2.91 | 1.85 | 52 |

| Depression | 2.31 | 1.92 | 38 | |

| PTSD | 14.78 | 6.29 | 52 | |

| Burnout | 3.05 | 1.18 | 61 | |

| March 2021 (n = 45) | Anxiety | 3.12 | 1.80 | 24 |

| Depression | 2.45 | 1.89 | 17 | |

| PTSD | 14.77 | 6.06 | 21 | |

| Burnout | 3.19 | 1.07 | 29 | |

| April 2021 (n = 64) | Anxiety | 3.14 | 1.79 | 41 |

| Depression | 2.63 | 1.83 | 26 | |

| PTSD | 14.89 | 6.12 | 37 | |

| Burnout | 3.14 | 1.11 | 45 | |

| May 2021 (n = 61) | Anxiety | 2.46 | 1.71 | 25 |

| Depression | 2.49 | 1.78 | 24 | |

| PTSD | 14.41 | 5.99 | 31 | |

| Burnout | 2.97 | 1.16 | 37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Habib, M.; Palachi, A.; Korman, M.B.; Steinberg, R.; Cocco, C.; Martin-Doto, C.; Tuka, A.; Cao, X.; Sinyor, M.; Ellis, J. Patterns of Distress and Supportive Resource Use by Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1785. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151785

Habib M, Palachi A, Korman MB, Steinberg R, Cocco C, Martin-Doto C, Tuka A, Cao X, Sinyor M, Ellis J. Patterns of Distress and Supportive Resource Use by Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1785. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151785

Chicago/Turabian StyleHabib, Mahiya, Aaron Palachi, Melissa B. Korman, Rosalie Steinberg, Claudia Cocco, Catherine Martin-Doto, Andrea Tuka, Xingshan Cao, Mark Sinyor, and Janet Ellis. 2025. "Patterns of Distress and Supportive Resource Use by Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1785. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151785

APA StyleHabib, M., Palachi, A., Korman, M. B., Steinberg, R., Cocco, C., Martin-Doto, C., Tuka, A., Cao, X., Sinyor, M., & Ellis, J. (2025). Patterns of Distress and Supportive Resource Use by Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare, 13(15), 1785. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151785

_Rachiotis.png)