Pediatricians’ Perspectives on Task Shifting in Pediatric Care: A Nationwide Survey in Japan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Ethical Considerations

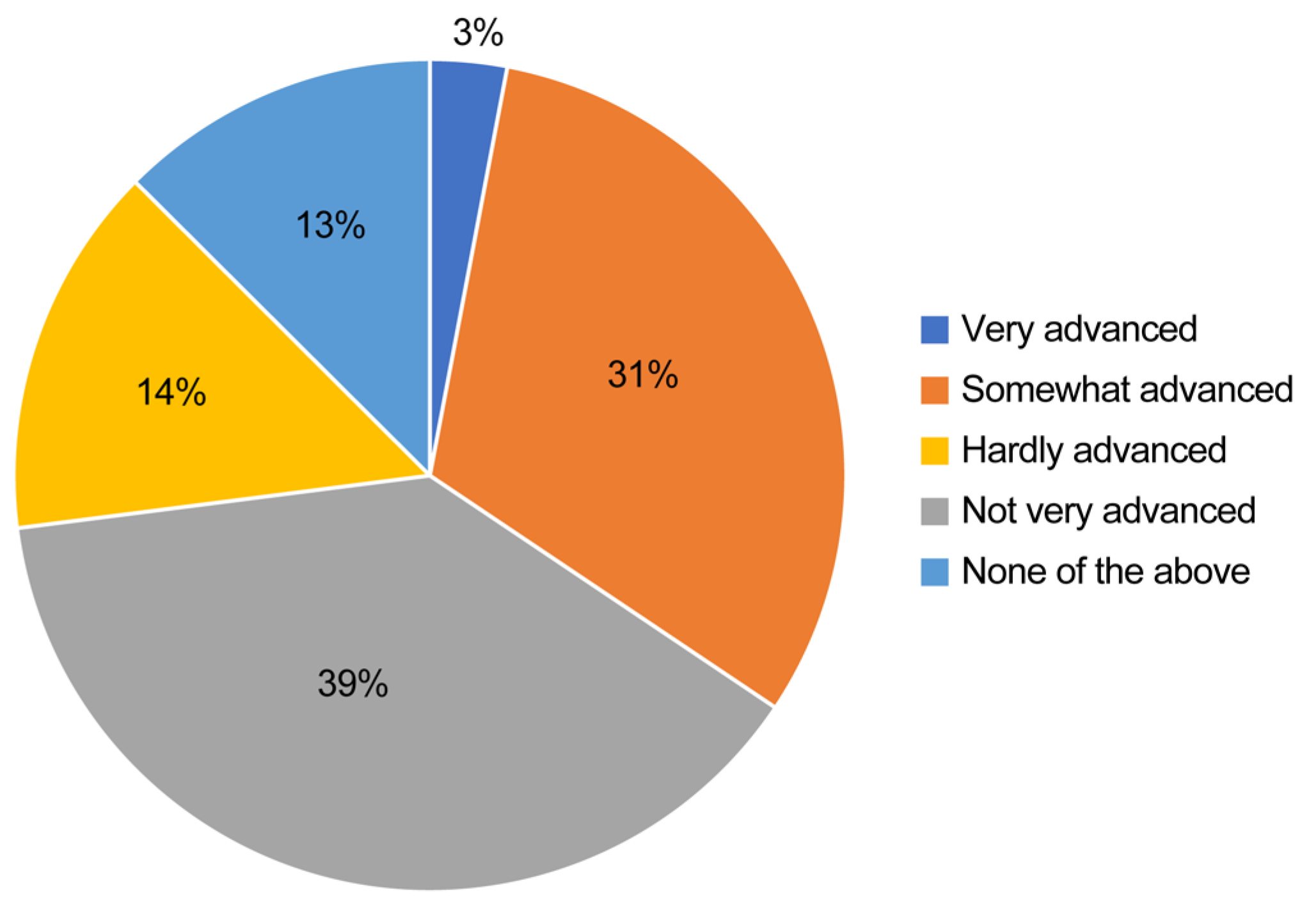

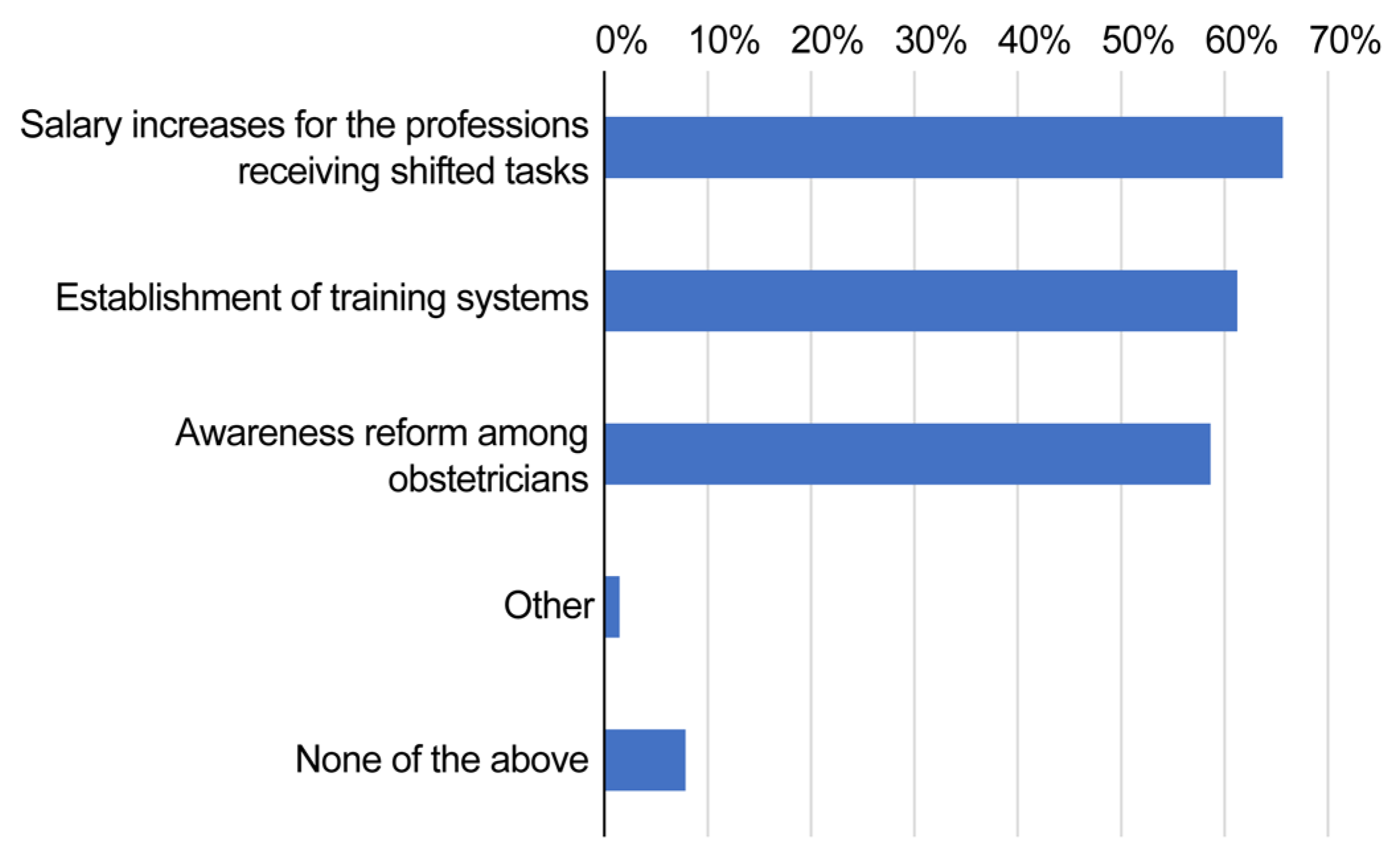

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- World Health Organization. Task Shifting Global Recommendations and Guidelines. 2008. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43821/9789241596312_eng.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Das, S.; Grant, L.; Fernandes, G. Task shifting healthcare services in the post-COVID world: A scoping review. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2023, 3, e0001712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okpechi, I.G.; Chukwuonye, I.I.; Ekrikpo, U.; Noubiap, J.J.; Raji, Y.R.; Adeshina, Y.; Ajayi, S.; Barday, Z.; Chetty, M.; Davidson, B.; et al. Task shifting roles, interventions and outcomes for kidney and cardiovascular health service delivery among African populations: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerene, D. Decentralisation and task-shifting in HIV care: Time to address emerging challenges. Public Health Action 2020, 10, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paier-Abuzahra, M.; Posch, N.; Jeitler, K.; Semlitsch, T.; Radl-Karimi, C.; Spary-Kainz, U.; Horvath, K.; Siebenhofer, A. Effects of task-shifting from primary care physicians to nurses: An overview of systematic reviews. Hum. Resour. Health 2024, 22, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penazzato, M.; Davies, M.A.; Apollo, T.; Negussie, E.; Ford, N. Task shifting for the delivery of pediatric antiretroviral treatment: A systematic review. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2014, 65, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Recommendations: Optimizing Health Worker Roles to Improve Access to Key Maternal and Newborn Health Interventions Through Task Shifting; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ogura, K. Long working hours in Japan; An international comparison and research topics. Jpn. Econ. 2009, 36, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, S.; Wada, H.; Ohde, S.; Ide, H.; Taneda, K.; Tanigawa, T. Working hours of full-time hospital physicians in Japan: A cross-sectional nationwide survey. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Report by the Study Group on the Work Style Reform for Doctors. (In Japanese). Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/newpage_04273.html (accessed on 29 March 2019).

- Ishikawa, M. The role of task shifting in reforming the working styles of pediatricians in Japan: A questionnaire survey. Medicine 2022, 101, e30167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Hospital bed function reporting system. 2024. (In Japanese). Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000055891.html (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Fukuda, A.; Watanabe, T.; Takahashi, Y. A study on regional disparities in the number of physicians by medical specialty and its trends. J. Jpn. Soc. Healthc. Admin 2018, 55, 9–18. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Urgent Measures for Reducing Doctors’ Working Hours. 2018. (In Japanese). Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10904750/000456412.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2018).

- Japan Pediatric Society. Hearing Materials on Promotion of Task Shifting. (In Japanese). Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10803000/000529935.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2019).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Physician, Dentist, and Pharmacist Statistics Overview. 2022. (In Japanese). Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/ishi/22/dl/R04_kekka-1.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Jones, L.; Exworthy, M.; Frosini, F. Implementing market-based reforms in the English NHS: Bureaucratic coping strategies and social embeddedness. Health Policy 2013, 111, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations; SAGE Publications: New Delhi, India, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Takamuku, M. Issues related to national university medical schools: Focusing on the low wages of University Hospital physicians. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi 2015, 116, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shibuya, K.; Unno, N. Unpaid doctors in Japanese university hospitals. Lancet 2019, 393, 1096–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. Publication of the Survey on the Treatment of Physicians and Dentists Other Than Faculty Members Engaged in Clinical Practice at University Hospitals. (In Japanese). Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/koutou/iryou/1418468.htm (accessed on 7 February 2020).

- Ishikawa, M. Time changes in the geographical distribution of physicians and factors associated with starting rural practice in Japan. Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 2020, 35, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, C.B.; Aiken, L.H. Task shifting from physicians to nurses in primary care in 39 countries: A cross-country comparative study. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgeault, I.L.; Mulvale, G. Collaborative health care teams in Canada and the USA: Confronting the structural embeddedness of medical dominance. Health Sociol. Rev. 2006, 15, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. of Respondents | 2043 | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 2041 | 99.9% |

| Male | 2 | 0.1% |

| Age, years | ||

| <30 | 434 | 21.2% |

| 30s | 503 | 24.6% |

| 40s | 602 | 29.5% |

| 50s | 443 | 21.7% |

| ≥60s | 61 | 3.0% |

| Qualifications | ||

| Midwife | 1640 | 80.3% |

| Registered nurse | 1463 | 71.6% |

| Licensed practical nurse | 99 | 4.8% |

| Advanced practice midwife | 397 | 19.4% |

| Job title | ||

| Staff | 1462 | 71.6% |

| Chief | 360 | 17.6% |

| Head nurse | 180 | 8.8% |

| Others | 41 | 2.0% |

| Foundational entity of employer | ||

| Public | 1262 | 61.8% |

| Private | 551 | 27.0% |

| Public university | 131 | 6.4% |

| Private university | 99 | 4.8% |

| Employer’s total no. of beds | ||

| <200 beds | 176 | 8.6% |

| ≥200 to <400 beds | 632 | 30.9% |

| ≥400 to <600 beds | 753 | 36.9% |

| ≥600 to <800 beds | 294 | 14.4% |

| ≥800 beds | 188 | 9.2% |

| Employer’s regional classification | ||

| Urban | 693 | 33.9% |

| Intermediate | 1062 | 52.0% |

| Rural | 288 | 14.1% |

| Number of full-time obstetricians | ||

| <5 | 841 | 41.2% |

| 5–9 | 858 | 42.0% |

| ≥10 | 293 | 14.3% |

| Unknown | 51 | 2.5% |

| Number of full-time midwives | ||

| <10 | 389 | 19.0% |

| 10–20 | 763 | 37.3% |

| 20–30 | 450 | 22.0% |

| ≥30 | 384 | 18.8% |

| Unknown | 57 | 2.8% |

| Number of full-time advanced practice midwives | ||

| <5 | 803 | 39.3% |

| 5–9 | 564 | 27.6% |

| ≥10 | 222 | 10.9% |

| Unknown | 454 | 22.2% |

| Annual delivery count | ||

| None | 45 | 2.2% |

| <200 | 509 | 24.9% |

| 200–400 | 714 | 34.9% |

| ≥400 | 642 | 31.4% |

| Unknown | 133 | 6.5% |

| Number of inpatient midwifery cases per year | ||

| None | 1468 | 71.9% |

| <200 | 302 | 14.8% |

| 200–400 | 43 | 2.1% |

| ≥400 | 13 | 0.6% |

| Unknown | 217 | 10.6% |

| Number of outpatient midwifery cases per year | ||

| None | 572 | 28.0% |

| <200 | 733 | 35.9% |

| 200–400 | 253 | 12.4% |

| ≥400 | 274 | 13.4% |

| Unknown | 211 | 10.3% |

| OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foundational entity of employer | |||

| Public | Reference | ||

| National university | 1.15 | 0.56–2.37 | 0.70 |

| Private university | 0.43 | 0.05–3.99 | 0.46 |

| Private | 2.13 | 0.35–12.90 | 0.41 |

| Total no. of beds | |||

| <200 beds | Reference | ||

| ≥200 to <400 beds | 0.55 | 0.23–1.33 | 0.19 |

| ≥400 to <600 beds | 0.35 | 0.14–0.84 | 0.02 |

| ≥600 to <800 beds | 0.19 | 0.05–0.73 | 0.02 |

| ≥800 beds | 0.34 | 0.06–1.87 | 0.22 |

| Workplace | |||

| Urban | Reference | ||

| Intermediate | 1.04 | 0.53–2.04 | 0.90 |

| Rural | 1.69 | 0.64–4.49 | 0.29 |

| Number of full-time obstetricians | |||

| <5 | Reference | ||

| 5–9 | 1.19 | 0.55–2.58 | 0.65 |

| ≥10 | 2.25 | 0.77–6.60 | 0.14 |

| Unknown | 0.38 | 0.04–3.96 | 0.42 |

| Number of full-time midwives | |||

| <10 | Reference | ||

| 10–20 | 0.38 | 0.15–0.96 | 0.04 |

| 20–30 | 0.73 | 0.25–2.11 | 0.57 |

| ≥30 | 0.41 | 0.12–1.42 | 0.16 |

| Unknown | 1.46 | 0.29–7.27 | 0.64 |

| Number of full-time advanced practice midwives | |||

| <5 | Reference | ||

| 5–9 | 0.69 | 0.32–1.49 | 0.35 |

| ≥10 | 0.53 | 0.19–1.49 | 0.23 |

| Unknown | 0.65 | 0.28–1.48 | 0.30 |

| Annual delivery count | |||

| None | Reference | ||

| <200 | 0.33 | 0.07–1.65 | 0.18 |

| 200–400 | 0.37 | 0.07–2.06 | 0.26 |

| ≥400 | 0.71 | 0.12–4.15 | 0.71 |

| Unknown | 0.28 | 0.04–2.20 | 0.23 |

| Number of inpatient midwifery cases per year | |||

| None | Reference | ||

| <200 | 4.02 | 2.02–7.99 | <0.01 |

| 200–400 | 7.60 | 2.22–26.09 | <0.01 |

| ≥400 | 2.53 | 0.47–13.54 | 0.28 |

| Unknown | 2.57 | 1.01–6.54 | 0.05 |

| Number of outpatient midwifery cases per year | |||

| None | Reference | ||

| <200 | 2.13 | 0.79–5.71 | 0.13 |

| 200–400 | 1.90 | 0.55–6.63 | 0.31 |

| ≥400 | 6.70 | 2.36–19.01 | <0.01 |

| Unknown | 2.88 | 0.81–10.22 | 0.10 |

| 1. Proxy entry tasks | ||||||||

| Task | Shifted | Should be shifted in the future | Should not be shifted | Neither | Shifted | Should be shifted in the future | Should not be shifted | Neither |

| Initial consultation interviews (preliminary questioning) | 960 | 221 | 425 | 437 | 47.0% | 10.8% | 20.8% | 21.4% |

| Order entry for tests, prescriptions, and procedures | 296 | 301 | 1011 | 435 | 14.5% | 14.7% | 49.5% | 21.3% |

| Hospitalization and surgery bookings | 272 | 370 | 984 | 417 | 13.3% | 18.1% | 48.2% | 20.4% |

| Preparation of medical certificates and referral letters | 263 | 267 | 1175 | 338 | 12.9% | 13.1% | 57.5% | 16.5% |

| Preparation of discharge summaries | 299 | 335 | 949 | 460 | 14.6% | 16.4% | 46.5% | 22.5% |

| Electronic medical chart entries | 261 | 261 | 1035 | 486 | 12.8% | 12.8% | 50.7% | 23.8% |

| Case registrations (e.g., cancer registration) | 141 | 372 | 963 | 567 | 6.9% | 18.2% | 47.1% | 27.8% |

| 2. Patient briefings and general procedures | ||||||||

| Task | Shifted | Should be shifted in the future | Should not be shifted | Neither | Shifted | Should be shifted in the future | Should not be shifted | Neither |

| Responding to telephone inquiries from patients | 1048 | 257 | 257 | 481 | 51.3% | 12.6% | 12.6% | 23.5% |

| Briefings using leaflets and video clips | 973 | 440 | 178 | 452 | 47.6% | 21.5% | 8.7% | 22.1% |

| Utilizing online medical consultations | 75 | 358 | 613 | 997 | 3.7% | 17.5% | 30.0% | 48.8% |

| Patient transfer (from operating room to hospital room, etc.) | 1297 | 245 | 178 | 323 | 63.5% | 12.0% | 8.7% | 15.8% |

| Sampling blood culture specimens | 1277 | 242 | 223 | 301 | 62.5% | 11.8% | 10.9% | 14.7% |

| Securing contrast agent lines | 1230 | 224 | 202 | 387 | 60.2% | 11.0% | 9.9% | 18.9% |

| Securing chemotherapy lines | 800 | 270 | 455 | 518 | 39.2% | 13.2% | 22.3% | 25.4% |

| 3. Obstetric-specific procedures | ||||||||

| Task | Shifted | Should be shifted in the future | Should not be shifted | Neither | Shifted | Should be shifted in the future | Should not be shifted | Neither |

| Routine fetal ultrasound | 244 | 326 | 836 | 637 | 11.9% | 16.0% | 40.9% | 31.2% |

| Screenings during prenatal check-ups | 221 | 174 | 1287 | 361 | 10.8% | 8.5% | 63.0% | 17.7% |

| Prescribing routine medications | 209 | 593 | 841 | 400 | 10.2% | 29.0% | 41.2% | 19.6% |

| Internal examinations during labor onset or rupture of membranes | 1324 | 169 | 197 | 353 | 64.8% | 8.3% | 9.6% | 17.3% |

| Starting labor-inducing drugs for weak contractions | 372 | 180 | 1150 | 341 | 18.2% | 8.8% | 56.3% | 16.7% |

| Adjustment of labor-inducing drugs | 1024 | 181 | 527 | 311 | 50.1% | 8.9% | 25.8% | 15.2% |

| Episiotomy and perineal suturing | 67 | 217 | 1354 | 405 | 3.3% | 10.6% | 66.3% | 19.8% |

| Bimanual uterine compression | 120 | 212 | 1194 | 517 | 5.9% | 10.4% | 58.4% | 25.3% |

| One-month postpartum check-up | 143 | 242 | 1166 | 492 | 7.0% | 11.8% | 57.1% | 24.1% |

| 4. Surgical procedures in obstetrics and gynecology | ||||||||

| Task | Shifted | Should be shifted in the future | Should not be shifted | Neither | Shifted | Should be shifted in the future | Should not be shifted | Neither |

| Assistant in obstetric and gynecological surgeries | 90 | 174 | 1318 | 461 | 4.4% | 8.5% | 64.5% | 22.6% |

| Intraoperative anesthesia, respiratory, and circulatory management | 439 | 107 | 1205 | 292 | 21.5% | 5.2% | 59.0% | 14.3% |

| Postoperative drain management and removal | 172 | 217 | 1203 | 451 | 8.4% | 10.6% | 58.9% | 22.1% |

| Postoperative CV removal and PICC insertion | 157 | 184 | 1300 | 402 | 7.7% | 9.0% | 63.6% | 19.7% |

| Postoperative wound management (cleaning, suturing, and staple removal) | 99 | 244 | 1262 | 438 | 4.8% | 11.9% | 61.8% | 21.4% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ishikawa, M.; Seto, R.; Oguro, M.; Sato, Y. Pediatricians’ Perspectives on Task Shifting in Pediatric Care: A Nationwide Survey in Japan. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1764. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141764

Ishikawa M, Seto R, Oguro M, Sato Y. Pediatricians’ Perspectives on Task Shifting in Pediatric Care: A Nationwide Survey in Japan. Healthcare. 2025; 13(14):1764. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141764

Chicago/Turabian StyleIshikawa, Masatoshi, Ryoma Seto, Michiko Oguro, and Yoshino Sato. 2025. "Pediatricians’ Perspectives on Task Shifting in Pediatric Care: A Nationwide Survey in Japan" Healthcare 13, no. 14: 1764. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141764

APA StyleIshikawa, M., Seto, R., Oguro, M., & Sato, Y. (2025). Pediatricians’ Perspectives on Task Shifting in Pediatric Care: A Nationwide Survey in Japan. Healthcare, 13(14), 1764. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141764