The Impact of Environmental Quality Dimensions and Green Practices on Patient Satisfaction from Students’ Perspective—Managerial and Financial Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Environmental Quality Dimensions

2.2. Green Practices

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Participants and Data Collection

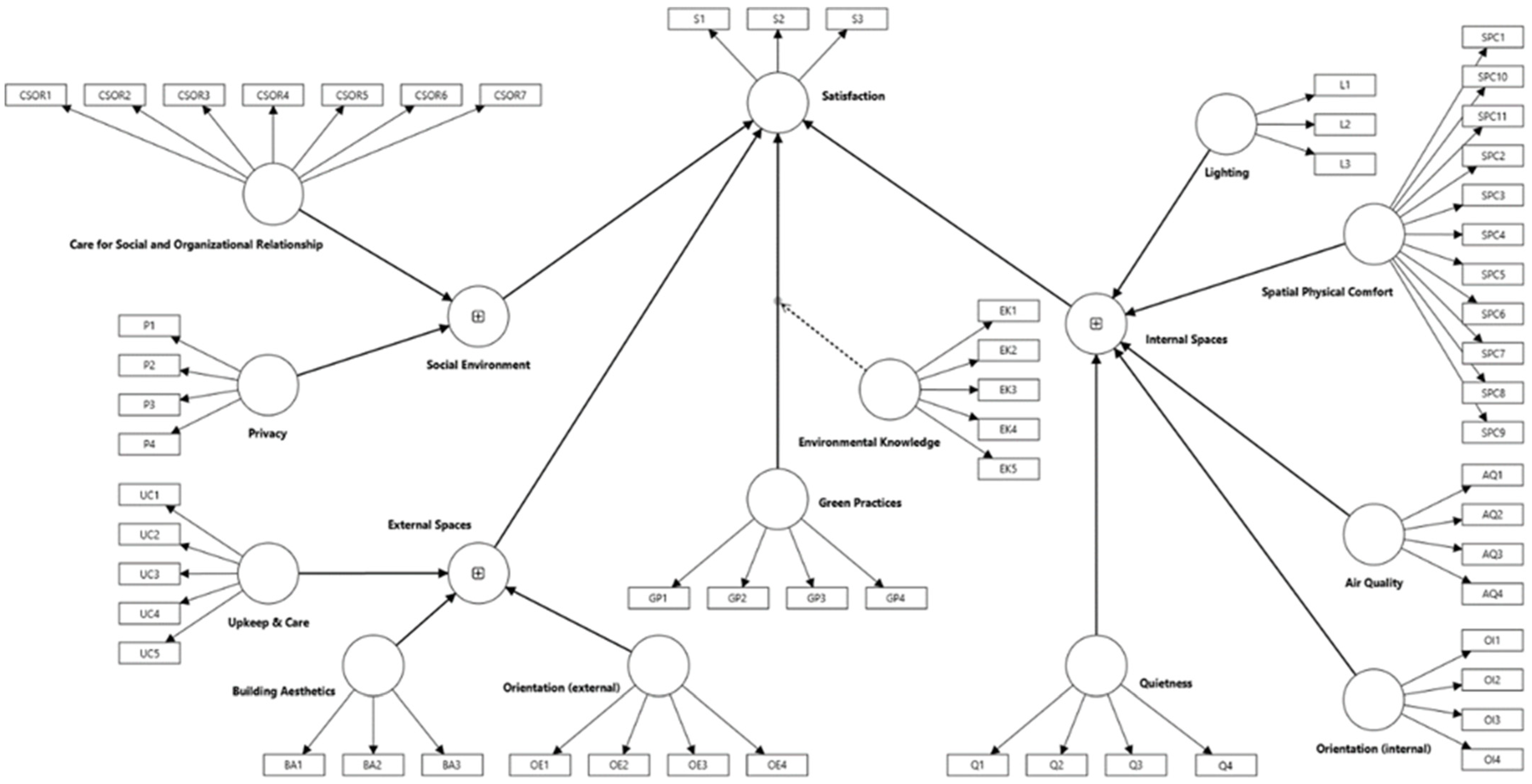

3.2. Instruments

3.3. Statistical Analysis

- Indicator reliability (outer loadings);

- Internal consistency reliability (Composite Reliability—CR, and Cronbach’s α);

- Convergent validity (Average Variance Extracted—AVE); and

- Discriminant validity (the application of the Fornell–Larcker and the HTMT criterion).

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Managerial Implications

6.2. Financial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gonzalez, M.E. Improving customer satisfaction of a healthcare facility: Reading the customers’ needs. Benchmarking Int. J. 2019, 26, 854–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baashar, Y.; Alhussian, H.; Patel, A.; Alkawsi, G.; Alzahrani, A.I.; Alfarraj, O.; Hayder, G. Customer relationship management systems (CRMS) in the healthcare environment: A systematic literature review. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2020, 71, 103442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtuluş, S.A.; Cengiz, E. Customer experience in healthcare: Literature review. Istanb. Bus. Res. 2022, 51, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Yun, G.W.; Friedman, S.; Hill, K.; Coppes, M.J. Patient-centered care and healthcare consumerism in online healthcare service advertisements: A positioning analysis. J. Patient Exp. 2022, 9, 23743735221133636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, L.J. Patient-centred care as an approach to improving health care in Australia. Collegian 2018, 25, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.K.; Frommelt, G.; Hazelwood, L.; Chang, R.W. The role of expectations in patient satisfaction with medical care. Mark. Health Serv. 1987, 7, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mutingi, M. Towards a customer-centric framework for evaluation of e-health service quality. In E-Manufacturing and E-Service Strategies in Contemporary Organizations; Gwangwava, N., Mutingi, M., Eds.; IGI Global: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calculli, C.; D’Uggento, A.M.; Labarile, A.; Ribecco, N. Evaluating people’s awareness about climate changes and environmental issues: A case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 324, 129244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marimuthu, M.; Paulose, H. Emergence of sustainability based approaches in healthcare: Expanding research and practice. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 224, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, F.; Di Gerio, C.; Fiorani, G.; Stola, G. How to manage sustainability in healthcare organizations? A processing map to include the ESG strategy. J. Public Budg. Account. Financ. Manag. 2024, 36, 636–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Ma, S.; Ur Rehman, A.; Usmani, Y.S. Green operation strategies in healthcare for enhanced quality of life. Healthcare 2023, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berniak-Woźny, J.; Rataj, M. Towards green and sustainable healthcare: A literature review and research agenda for green leadership in the healthcare sector. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.L.; Buttigieg, S.C.; Bak, B.; McFadden, S.; Hughes, C.; McClure, P.; Couto, J.G.; Bravo, I. A review of the applicability of current green practices in healthcare facilities. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2023, 12, 6947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Health-Care Waste; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/health-care-waste (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Orsini, L.P.; Landi, S.; Leardini, C.; Veronesi, G. Towards greener hospitals: The effect of green organisational practices on climate change mitigation performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 462, 142720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, V.S.; Kaur, D. Green hospital and climate change: Their interrelationship and the way forward. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, LE01–LE05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shehri, S.N. Healthy students–healthy nation. J. Fam. Community Med. 2002, 9, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart-Brown, S.; Evans, J.; Patterson, J.; Petersen, S.; Doll, H.; Balding, J.; Regis, D. The health of students in institutes of higher education: An important and neglected public health problem? J. Public Health 2000, 22, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder-Pelz, S. Toward a theory of patient satisfaction. Soc. Sci. Med. 1982, 16, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B. Patient satisfaction: A valid concept? Soc. Sci. Med. 1994, 38, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitzia, J.; Wood, N. Patient satisfaction: A review of issues and concepts. Soc. Sci. Med. 1997, 45, 1829–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andaleeb, S.S. Service quality perceptions and patient satisfaction: A study of hospitals in a developing country. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 52, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senić, V.; Marinković, V. Patient care, satisfaction and service quality in health care. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Muhammad, N.; Mahmood, H.; Yen, Y.Y. The influence of healthcare service quality on patients’ satisfaction in urban areas: The case of Pakistan. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Sashikala, P.; Roy, S. Green–agile practices as drivers for patient satisfaction—An empirical study. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2022, 15, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, F.; Wei, L.; Hussain, A.; Asif, M.; Shah, S.I.A. Patient satisfaction with health care services; an application of physician’s behavior as a moderator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C.; Lima, M.L.; Fornara, F.; Bonaiuto, M. Users’ views of hospital environmental quality: Validation of the perceived hospital environment quality indicators (PHEQIs). J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 97–111, Erratum in J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 238–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornara, F.; Bonaiuto, M.; Bonnes, M. Perceived hospital environment quality indicators: A study of orthopaedic units. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadmi, E. Quality of hospital to community care transitions: The experience of minority patients. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2013, 25, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C.C.; Lima, M.L.; Pereira, C.R.; Fornara, F.; Bonaiuto, M. Inpatients’ and outpatients’ satisfaction: The mediating role of perceived quality of physical and social environment. Health Place 2013, 21, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaVela, S.L.; Etingen, B.; Hill, J.N.; Miskevics, S. Patient perceptions of the environment of care in which their healthcare is delivered. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2016, 9, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisberg, A.; Syn-Hershko, A. Factors related to the mobility of hospitalized older adults: A prospective cohort study. Geriatr. Nurs. 2016, 37, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Moradi, A.; Hosseini, S.B.; Shamloo, G. Evaluating the impact of environmental quality indicators on the degree of humanization in healing environments. Space Ontol. Int. J. 2018, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Manca, S.; Bonaiuto, M.; Fornara, F. Perceived hospital environment quality indicators: The case of healthcare places for terminal patients. Buildings 2023, 13, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edris, N.; Bashir, F.; Zeleke, B. Impacts of hospitals users’ characteristics on perceptions of the physical environment. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahrinasari, M.S.; Haseeb, M.; Bangsawan, S.; Sabri, M.F.; Daud, N.M. Effects of Green Operational Practices and E-CRM on Patient Satisfaction among Indonesian Hospitals: Exploring the Moderating Role of Green Social Influence. Oper. Res. Eng. Sci. Theory Appl. 2023, 6, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moise, M.S.; Gil-Saura, I.; Ruiz-Molina, M.E. “Green” practices as antecedents of functional value, guest satisfaction and loyalty. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2021, 4, 722–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Viralta, D.; Veas-González, I.; Egaña-Bruna, F.; Vidal-Silva, C.; Delgado-Bello, C.; Pezoa-Fuentes, C. Positive effects of green practices on the consumers’ satisfaction, loyalty, word-of-mouth, and willingness to pay. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, K.N.; Nhan, D.H.; Nguyen, P.T.M. Empirical study of green practices fostering customers’ willingness to consume via customer behaviors: The case of green restaurants in Ho Chi Minh City of Vietnam. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, P.; Kulshreshtha, K.; Tripathi, V.; Agnihotri, D. Investigating the impact of restaurants’ sustainable practices on consumers’ satisfaction and revisit intentions: A study on leading green restaurants. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2024, 16, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryxell, G.E.; Lo, C.W. The influence of environmental knowledge and values on managerial behaviours on behalf of the environment: An empirical examination of managers in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 46, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Molina, M.A.; Fernández-Sáinz, A.; Izagirre-Olaizola, J. Environmental knowledge and other variables affecting pro-environmental behaviour: Comparison of university students from emerging and advanced countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 61, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, Y. Pro-environmental awareness and behaviors on campus: Evidence from Tianjin, China. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2018, 14, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Teng, M.; Han, C. How does environmental knowledge translate into pro-environmental behaviors?: The mediating role of environmental attitudes and behavioral intentions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraj-Andrés, E.; Martínez-Salinas, E. Impact of environmental knowledge on ecological consumer behaviour: An empirical analysis. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2007, 19, 73–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, M.I.; Tanwir, N.S. Do pro-environmental factors lead to purchase intention of hybrid vehicles? The moderating effects of environmental knowledge. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ryu, Y.; Kim, Y. Factors influencing air passengers’ intention to purchase voluntary carbon offsetting programs: The moderating role of environmental knowledge. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2024, 118, 102619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issock Issock, P.B.; Mpinganjira, M.; Roberts-Lombard, M. Modelling green customer loyalty and positive word of mouth: Can environmental knowledge make the difference in an emerging market? Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2020, 15, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Serbia. Belgrade. 2021. Available online: https://publikacije.stat.gov.rs/G2021/PdfE/G20212054.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Serbia. Belgrade. 2022. Available online: https://publikacije.stat.gov.rs/G2022/pdf/G20222055.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Serbia. Belgrade. 2023. Available online: https://publikacije.stat.gov.rs/G2023/Pdf/G20232056.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Myung, E. Environmental knowledge, attitudes, and willingness to pay for environmentally friendly meetings–An exploratory study. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 36, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.M.; Klein, K.; Wetzels, M. Hierarchical Latent Variable Models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for Using Reflective-Formative Type Models. Long. Range Plan. 2012, 45, 359–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.P.; Lin, Y.L.; Shiau, W.L.; Chen, S.F. Investigating common method bias via an EEG study of the flow experience in website design. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 22, 305–321. [Google Scholar]

- Fleuren, B.; van Amelsvoort, L.; Zijlstra, F.R.H.; de Grip, A.; Kant, I. Handling the reflectiveformative measurement conundrum: A practical illustration based on sustainable employability. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 103, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Ven, A.H. What matters most to patients? Participative provider care and staff courtesy. Patient Exp. J. 2014, 1, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asres, A.W.; Hunegnaw, W.A.; Ferede, A.G.; Denekew, H.T. Assessment of patient satisfaction and associated factors in an outpatient department at Dangila primary hospital, Awi zone, Northwest Ethiopia, 2018. Glob. Secur. Health Sci. Policy 2020, 5, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.K.M.; Cheng, E.W.L. Green purchase behavior of undergraduate students in Hong Kong. Soc. Sci. J. 2016, 53, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Manrai, A.K.; Manrai, L.A. Purchasing behaviour for environmentally sustainable products: A conceptual framework and empirical study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, F.P.B.; Sousa, K.H.J.F.; Tomaz, A.P.K.D.A.; Tracera, G.M.P.; Santos, K.M.D.; Oliveira, E.B.D.; Zeitoune, R.C.G. Nursing career anchors and professional exercise: Is there alignment? Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2021, 74, e20200591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, H.; Evans, M.; Farrell, P. Hospitals management transformative initiatives; towards energy efficiency and environmental sustainability in healthcare facilities. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2023, 21, 552–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khahro, S.H.; Kumar, D.; Siddiqui, F.H.; Ali, T.H.; Raza, M.S.; Khoso, A.R. Optimizing Energy Use, Cost and Carbon Emission through Building Information Modelling and a Sustainability Approach: A Case-Study of a Hospital Building. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicators | Outer Loadings | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care for Social and Organizational Relationship (CSOR) | 0.903 | 0.609 | 0.871 | |

| (CSOR1) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, people receive a nice welcome from staff. | 0.815 | |||

| (CSOR2) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, doctors are generally not very understanding toward patients. | 0.823 | |||

| (CSOR3) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, nurses are generally not very understanding toward patients. | 0.793 | |||

| (CSOR4) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, doctors generally provide poor information on medical examinations, therapies, and interventions. | 0.746 | |||

| (CSOR5) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, there is a good cooperative atmosphere among staff members. | 0.709 | |||

| (CSOR6) The Institute for Student Health Protection is poorly organized. | 0.791 | |||

| Privacy (P) | 0.929 | 0.867 | 0.847 | |

| (P1) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, you can talk to staff about delicate issues without being overheard by others. | 0.929 | |||

| (P4) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, people can have their own privacy. | 0.933 | |||

| Upkeep and Care (UC) | 0.888 | 0.725 | 0.809 | |

| (UC3) In the external area of the Institute for Student Health Protection, paths and sidewalks are in good condition. | 0.845 | |||

| (UC4) The external area of the Institute for Student Health Protection is well-kept. | 0.912 | |||

| (UC5) The external area of the Institute for Student Health Protection is not very clean. | 0.793 | |||

| Building Aesthetics (BA) | 0.898 | 0.747 | 0.830 | |

| (BA1) From the outside, the building of the Institute for Student Health Protection is nice. | 0.824 | |||

| (BA2) From the outside, the colors of the building of the Institute for Student Health Protection are unpleasant. | 0.885 | |||

| (BA3) From the outside, the shape of the building of the Institute for Student Health Protection is unpleasant. | 0.882 | |||

| Orientation (external) (OE) | 0.913 | 0.779 | 0.858 | |

| (OE2) It is easy to find the Institute for Student Health Protection. | 0.903 | |||

| (OE3) It is easy to find the entrance of the Institute for Student Health Protection. | 0.875 | |||

| (OE4) It is difficult to get oriented and find the Institute for Student Health Protection. | 0.869 | |||

| Lighting (L) | 0.829 | 0.619 | 0.704 | |

| (L1) There is not enough sunlight in the Institute for Student Health Protection. | 0.840 | |||

| (L2) The Institute for Student Health Protection has large windows. | 0.726 | |||

| (L3) The Institute for Student Health Protection needs more windows. | 0.791 | |||

| Spatial Physical Comfort (SPC) | 0.928 | 0.618 | 0.912 | |

| (SPC1) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, furnishings are in good condition. | 0.805 | |||

| (SPC2) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, furnishings are unpleasant. | 0.796 | |||

| (SPC3) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, the quality of furnishings is good. | 0.826 | |||

| (SPC4) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, walls, floors, and ceilings are well kept. | 0.814 | |||

| (SPC5) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, walls, floors, and ceilings have nice colors. | 0.777 | |||

| (SPC6) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, walls, floors, and ceilings are in poor condition. | 0.776 | |||

| (SPC7) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, walls, floors, and ceilings are unpleasant. | 0.771 | |||

| (SPC9) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, seats are uncomfortable. | 0.722 | |||

| Air Quality (AQ) | 0.897 | 0.743 | 0.827 | |

| (AQ2) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, the air exchange from outside is adequate. | 0.881 | |||

| (AQ3) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, air humidity is adequate (neither too wet nor too dry). | 0.836 | |||

| (AQ4) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, the air is not fresh. | 0.869 | |||

| Orientation (internal) (OI) | 0.918 | 0.849 | 0.822 | |

| (OI3) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, information point(s) is (are) badly located. | 0.925 | |||

| (OI4) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, you can easily find information point(s). | 0.918 | |||

| Quietness (Q) | 0.914 | 0.728 | 0.874 | |

| (Q1) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, there is enough quietness. | 0.870 | |||

| (Q2) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, you can hear dins and screams. | 0.898 | |||

| (Q3) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, you can hear little noise from outside. | 0.872 | |||

| (Q4) In the Institute for Student Health Protection, you can often hear noise from the outside. | 0.768 | |||

| Green Practices (GP) | 0.909 | 0.715 | 0.868 | |

| (GP1) The healthcare institute respects the environmental norms defined in the law when carrying out its activities. | 0.836 | |||

| (GP2) The healthcare institute tries to improve its green practices. | 0.837 | |||

| (GP3) The healthcare institute is concerned with respecting and protecting the natural environment. | 0.893 | |||

| (GP4) The healthcare institute is concerned with improving the general well-being of society. | 0.815 | |||

| Environmental Knowledge (EK) | 0.880 | 0.787 | 0.762 | |

| (EK3) I know the meaning of “acid rain”. | 0.964 | |||

| (EK4) I know what the problem of ozone depletion is. | 0.802 | |||

| Satisfaction (S) | 0.928 | 0.811 | 0.884 | |

| (S1) Overall, I am satisfied with the services of the Institute for Student Health Protection. | 0.891 | |||

| (S2) The overall organization of the Institute for Student Health Protection is above my expectations. | 0.900 | |||

| (S3) The Institute for Student Health Protection is close to delivering ideal service. | 0.911 |

| AQ | BA | CSOR | EK | GP | L | OE | OI | P | Q | S | SPC | UC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQ | 0.862 | ||||||||||||

| BA | 0.307 | 0.864 | |||||||||||

| CSOR | 0.472 | 0.381 | 0.780 | ||||||||||

| EK | 0.036 | −0.048 | −0.029 | 0.887 | |||||||||

| GP | 0.512 | 0.350 | 0.623 | −0.072 | 0.846 | ||||||||

| L | 0.409 | 0.307 | 0.320 | −0.038 | 0.280 | 0.787 | |||||||

| OE | 0.329 | 0.363 | 0.305 | 0.031 | 0.210 | 0.210 | 0.882 | ||||||

| OI | 0.448 | 0.277 | 0.427 | 0.015 | 0.410 | 0.231 | 0.318 | 0.921 | |||||

| P | 0.376 | 0.335 | 0.582 | −0.008 | 0.531 | 0.226 | 0.286 | 0.333 | 0.931 | ||||

| Q | 0.481 | 0.273 | 0.445 | 0.074 | 0.440 | 0.204 | 0.194 | 0.453 | 0.504 | 0.853 | |||

| S | 0.460 | 0.335 | 0.722 | −0.100 | 0.666 | 0.301 | 0.323 | 0.391 | 0.557 | 0.358 | 0.901 | ||

| SPC | 0.524 | 0.588 | 0.534 | −0.060 | 0.561 | 0.400 | 0.303 | 0.356 | 0.427 | 0.350 | 0.532 | 0.786 | |

| UC | 0.413 | 0.395 | 0.444 | −0.004 | 0.348 | 0.230 | 0.252 | 0.366 | 0.344 | 0.410 | 0.315 | 0.386 | 0.852 |

| AQ | BA | CSOR | EK | GP | L | OE | OI | S | P | Q | SPC | UC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQ | |||||||||||||

| BA | 0.369 | ||||||||||||

| CSOR | 0.556 | 0.447 | |||||||||||

| EK | 0.068 | 0.082 | 0.062 | ||||||||||

| GP | 0.603 | 0.410 | 0.704 | 0.104 | |||||||||

| L | 0.517 | 0.387 | 0.372 | 0.065 | 0.323 | ||||||||

| OE | 0.389 | 0.426 | 0.352 | 0.072 | 0.238 | 0.267 | |||||||

| OI | 0.542 | 0.333 | 0.503 | 0.083 | 0.482 | 0.283 | 0.377 | ||||||

| S | 0.537 | 0.390 | 0.822 | 0.135 | 0.747 | 0.356 | 0.369 | 0.459 | |||||

| P | 0.448 | 0.399 | 0.678 | 0.036 | 0.608 | 0.268 | 0.333 | 0.398 | 0.643 | ||||

| Q | 0.564 | 0.316 | 0.509 | 0.110 | 0.497 | 0.233 | 0.222 | 0.533 | 0.407 | 0.584 | |||

| SPC | 0.602 | 0.678 | 0.598 | 0.088 | 0.629 | 0.473 | 0.339 | 0.409 | 0.593 | 0.485 | 0.390 | ||

| UC | 0.505 | 0.482 | 0.530 | 0.081 | 0.410 | 0.282 | 0.301 | 0.447 | 0.372 | 0.415 | 0.486 | 0.448 |

| Lower-Order Constructs | Higher-Order Constructs | Path Coefficients | p Values | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air Quality | Internal Spaces | 0.227 | p < 0.001 | 1.781 |

| Lighting | 0.124 | p < 0.001 | 1.275 | |

| Orientation (internal) | 0.137 | p < 0.001 | 1.401 | |

| Quietness | 0.247 | p < 0.001 | 1.445 | |

| Spatial Physical Comfort | 0.585 | p < 0.001 | 1.509 | |

| Privacy | Social Environment | 0.298 | p < 0.001 | 1.513 |

| Care for Social and Organizational Relationships | 0.797 | p < 0.001 | 1.513 | |

| Building Aesthetics | External Spaces | 0.472 | p < 0.001 | 1.299 |

| Orientation (external) | 0.452 | p < 0.001 | 1.171 | |

| Upkeep and Care | 0.413 | p < 0.001 | 1.205 |

| Relations | Path Coeff. | p Values | ƒ2 | VIF | Hypotheses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Spaces → Satisfaction | 0.003 | 0.949 | 0.000 | 1.755 | H1 Rejected |

| Internal Spaces → Satisfaction | 0.084 | 0.187 | 0.007 | 2.600 | H2 Rejected |

| Social Environment → Satisfaction | 0.502 | p < 0.001 | 0.298 | 2.203 | H3 Supported |

| Green Practices → Satisfaction | 0.273 | p < 0.001 | 0.089 | 2.169 | H4 Supported |

| Env. Knowledge x Green Practices → Satisfaction | 0.011 | 0.766 | 0.000 | 1.147 | H5 Rejected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Milicevic, N.; Djokic, N.; Djokic, I.; Radic, J.; Berber, N.; Kalas, B. The Impact of Environmental Quality Dimensions and Green Practices on Patient Satisfaction from Students’ Perspective—Managerial and Financial Implications. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1673. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141673

Milicevic N, Djokic N, Djokic I, Radic J, Berber N, Kalas B. The Impact of Environmental Quality Dimensions and Green Practices on Patient Satisfaction from Students’ Perspective—Managerial and Financial Implications. Healthcare. 2025; 13(14):1673. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141673

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilicevic, Nikola, Nenad Djokic, Ines Djokic, Jelena Radic, Nemanja Berber, and Branimir Kalas. 2025. "The Impact of Environmental Quality Dimensions and Green Practices on Patient Satisfaction from Students’ Perspective—Managerial and Financial Implications" Healthcare 13, no. 14: 1673. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141673

APA StyleMilicevic, N., Djokic, N., Djokic, I., Radic, J., Berber, N., & Kalas, B. (2025). The Impact of Environmental Quality Dimensions and Green Practices on Patient Satisfaction from Students’ Perspective—Managerial and Financial Implications. Healthcare, 13(14), 1673. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141673