Physician and Patient Dissatisfaction with Outpatient Pre-Screening Triage in Public Dental Hospitals: Scope and Strategies for Improvement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Main Variables

2.3. Sample Size Calculation

2.4. Statistical Analysis

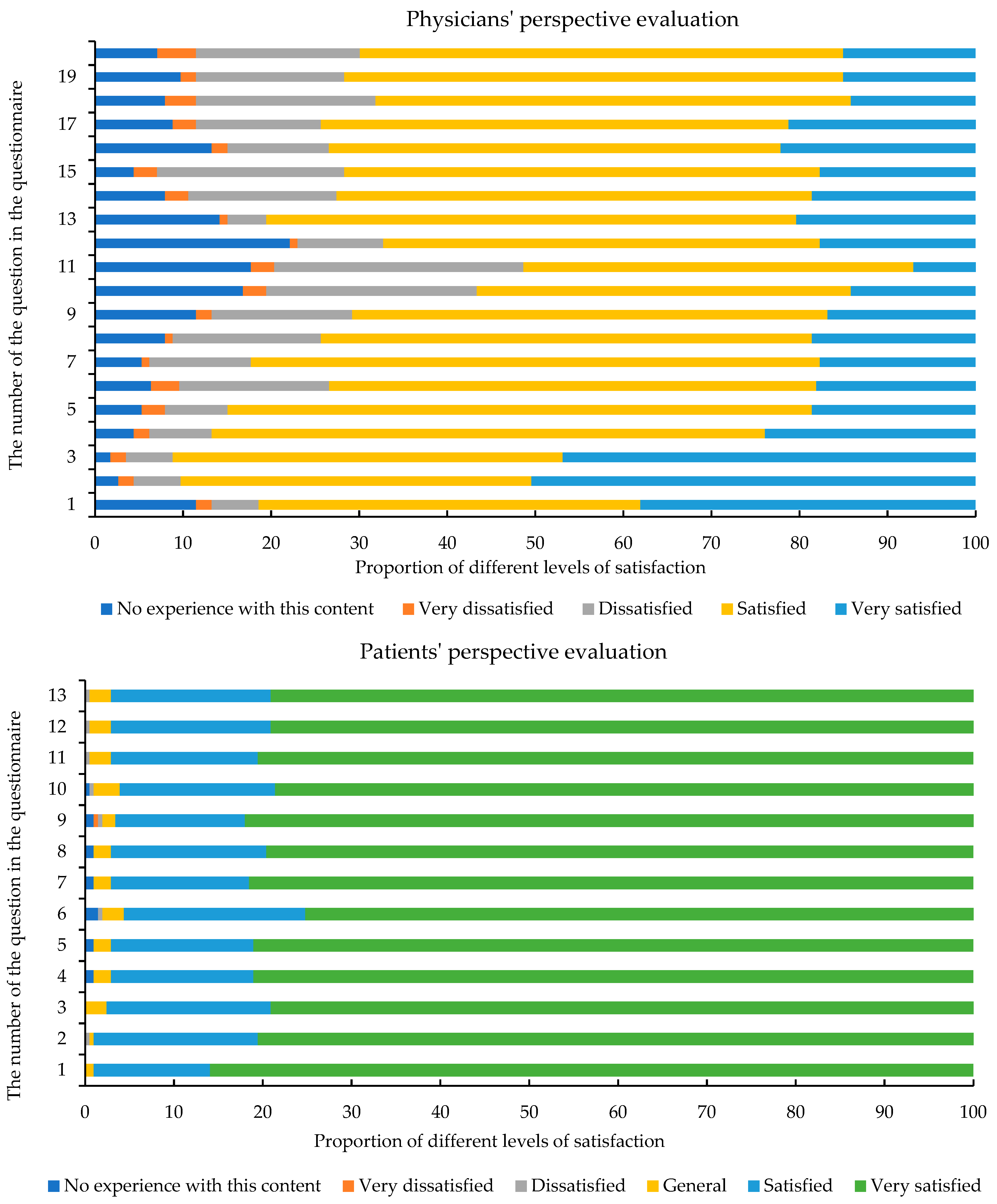

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Physician Characteristics

3.3. Patient Characteristics

4. Discussion

4.1. Decreased Physician Satisfaction Under PST Implementation: Systemic Challenges and the Need for Policy Responses

4.2. Mitigating High Patient Dissatisfaction in Dental Center: A Trinity Approach of Environmental, Process, and Humanistic Enhancements

4.3. Limitations and Advantages

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mitchell, R. Triage for resource-limited emergency care: Why it matters. Emerg. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 3, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, N.; Zhang, H.; Yang, H.; Yang, J. Roles and Challenges for Village Doctors in COVID-19 Pandemic Prevention and Control in Rural Beijing, China: A Qualitative Study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 888374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausserhofer, D.; Zaboli, A.; Pfeifer, N.; Solazzo, P.; Magnarelli, G.; Marsoner, T.; Siller, M.; Turcato, G. Errors in nurse-led triage: An observational study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 113, 103788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, S.A.; Ali, P.A. A review of factors affecting patient satisfaction with nurse led triage in emergency departments. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2016, 29, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaazmi, S.; Simsekler, M.C.E.; Henschel, A.; Qazi, A.; Marbouh, D.; Luqman, R. Evaluating Drivers of the Patient Experience Triangle: Stress, Anxiety, and Frustration. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariasse, J.M.; van der Hagen, V.; Seiger, N.; Mackway-Jones, K.; van Veen, M.; Moll, H.A. Performance of triage systems in emergency care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; O’Reilly, G.; Banks, C.; Nou, G.; McKup, J.J.; Kingston, C.; Kendino, M.; Piamnok, D.; Cameron, P. Triage systems in low-resource emergency care settings. Bull. World Health Organ. 2025, 103, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Cai, Y.T.; Cai, X.; Wen, X.L.; Wang, J.Y.; Ma, W.C.; Shen, J.; Wu, J.X.; Liu, H.Y.; Sun, J.; et al. Management and implementation strategies of pre-screening triage in children during coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in Guangzhou, China. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 2731–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuzeng, S.; Hui, L.L. Improving the wait time to triage at the emergency department. BMJ Open Qual. 2020, 9, e000708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, M.; Farcy, D.A.; Moreno, L.A.; Vilke, G.M.; Guittard, J.A. Triage Nurse-Ordered Testing in the Emergency Department Setting: A Review of the Literature for the Clinician. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 60, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barajas, G.; Zembower, T.; Silkaitis, C.; Brennan, J.; Brassil, E.; Nozicka, N.; Groth, M.; Ward-Fore, S.; Lau, M.; Sanders, L.; et al. Triage documentation-based decision support to improve infectious disease risk screening and mitigate exposure. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2016, 44, 1063–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domagała, A.; Bała, M.M.; Storman, D.; Peña-Sánchez, J.N.; Świerz, M.J.; Kaczmarczyk, M.; Storman, M. Factors Associated with Satisfaction of Hospital Physicians: A Systematic Review on European Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliberato, R.O.; Rocha, L.L.; Lima, A.H.; Santiago, C.R.; Terra, J.C.; Dagan, A.; Celi, L.A. Physician satisfaction with a multi-platform digital scheduling system. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, M.; Paudel, N.R.; Mishra, S.R.; Shrestha, A.; Upadhyaya, D.P. Patient satisfaction and its socio-demographic correlates in a tertiary public hospital in Nepal: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, W.; Yu, Z.; Yu, J.; Lin, Y.; Li, X.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, Y. How does overall hospital satisfaction relate to patient experience with nursing care? A cross-sectional study in China. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e053899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentapati, K.C.; Chenna, D.; Kumar, V.S.; Kumar, N.; Kumar, S. Child Oral Health Impact Profile Questionnaire: A Reliability Generalization Meta-analysis of Cronbach’s Alpha. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 17, 1193–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimberlin, C.L.; Winterstein, A.G. Validity and reliability of measurement instruments used in research. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2008, 65, 2276–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Liu, D.; Ali, S. Patient dissatisfaction in China: What matters. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 143, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Su, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, D. Dissatisfaction with Local Medical Services for Middle-Aged and Elderly in China: What Is Relevant? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Xu, Y. Medical Statistics, 3rd ed.; People’s Medical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. The Fourth National Oral Health Epidemiological Survey Report, 1st ed.; People’s Medical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Heggie, C. Triaging of non-scheduled appointments in general dental practice: A clinical audit. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 226, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saade, Y.; de la Dure Molla, M.; Fournier, B.P.J.; Kerner, S.; Colon, P.; Carra, M.C.; Bouchard, P. The dental triage method at Rothschild Hospital during the first lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkola, M.K.; Gästgifvars, J.J.; Helenius-Hietala, J.S.; Uittamo, J.T.; Furuholm, J.O.; Välimaa, H.; Ruokonen, H.M.A.; Nylund, K.M. Triage and urgent dental care for COVID-19 patients in the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2022, 80, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Lin, H. The role of triage in the prevention and control of COVID-19. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020, 41, 772–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifford, M.; McEllistrem, B.; Jones, D. Exploring the preparedness of newly qualified general practitioners for independent practice in Ireland. Educ. Prim. Care 2023, 34, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Schwebel, D.C.; Hu, G. Physicians’ Workloads in China: 1998–2016. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Shanafelt, T.D. Physician burnout: Contributors, consequences and solutions. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 283, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nia, A.; Zavlin, D. The Burden of Physicians’ Administrative Workload Affects Clinical and Scientific Mentoring. MedEdPublish 2019, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, E.; Cronin, S.; Murphy, N.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S.; MacSweeney, K.; Bates, M.; Fahey, T. Characterising patient complaints in out-of-hours general practice: A retrospective cohort study in Ireland. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 68, e860–e868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, E.G. Harmful Emotional Responses that Patients and Physicians May Have When their Values Conflict. J. Clin. Ethics 2016, 27, 187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, C.I.; Kuo, R.N.; Liang, C.C.; Tsai, H.Y.; Chung, K.P. Differences in the outcomes of adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer prescribed by physicians in different disciplines: A population-based study in Taiwan. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; He, X.; Wu, J.; Xie, F. Differences between physician and patient preferences for cancer treatments: A systematic review. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldas, W.; Bonin, F.A.; Vianna, C.P.; Shimizu, R.H.; Trojan, L.C. Influence of pain duration and severity on oral health-related quality of life and patient satisfaction during adult treatment with clear aligners. Prog. Orthod. 2024, 25, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, J.L., III; Gilbert, G.H.; Heft, M.W. Orofacial pain: Patient satisfaction and delay of urgent care. Public Health Rep. 2005, 120, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licciardone, J.C.; Patel, S.; Kandukuri, P.; Beeton, G.; Nyalakonda, R.; Aryal, S. Patient Satisfaction with Medical Care for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Pain Research Registry Study. Ann. Fam. Med. 2023, 21, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akintomide, A.O.; Ukweh, O.N.; Efanga, S.A. An audit of the appointment booking system and patient waiting time in an ultrasound unit in Nigeria: A need to eliminate congestion in our public hospitals. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 2055–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, S.; Barnes, S.R. Understanding congestion in China’s medical market: An incentive structure perspective. Health Policy Plan. 2016, 31, 390–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Outcome Variables | Classification Methods |

|---|---|

| Physicians’ Perspective (n = 113) | |

| Continuous variable | The sum of the answers to all questions is the continuous variable for physician dissatisfaction ratings, ranging from 0 to 80, with higher scores being associated with higher levels of dissatisfaction. |

| Binary variable | The groups dissatisfied and very dissatisfied were combined as dissatisfied and denoted by 1, and the other groups were combined as “Other” and denoted by 0. |

| Patients’ Perspective (n = 206) | |

| Continuous variable | The sum of the answers to all questions is the continuous variable for physician dissatisfaction ratings, ranging from 0 to 52, with higher scores being associated with higher levels of dissatisfaction. |

| Binary variable | The groups dissatisfied and very dissatisfied were combined as dissatisfied and denoted by 1, and the other groups were combined as “Other” and denoted by 0. |

| Variables | Groups | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians’ Perspective (n = 113) | |||

| Pre-screening triage experience | |||

| No | 42 | 62.83 | |

| Yes | 71 | 37.17 | |

| Type of pre-screening and triage center | |||

| A | 30 | 26.55 | |

| B | 39 | 34.51 | |

| C | 23 | 20.35 | |

| D | 21 | 18.58 | |

| Professional title | Junior | 56 | 49.56 |

| Intermediate | 42 | 37.17 | |

| Senior | 15 | 13.27 | |

| Years of work experience | |||

| ≤3 | 46 | 40.71 | |

| 4–6 | 14 | 12.39 | |

| ≥7 | 53 | 46.90 | |

| Patients’ Perspective (n = 206) | |||

| Gender | Male | 91 | 44.17 |

| Female | 115 | 55.83 | |

| Age | ≤17 years old | 22 | 10.68 |

| 18–59 years old | 151 | 73.30 | |

| ≥60 years old | 33 | 16.02 | |

| Type of pre-screening and triage center | |||

| A | 27 | 13.11 | |

| B | 39 | 18.93 | |

| C | 107 | 51.94 | |

| D | 33 | 16.02 | |

| Variables | Total Score | p | Dissatisfaction [n (%)] | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||

| Physicians’ Perspective (n = 113) | |||||

| Pre-screening triage experience | 0.006 | 0.071 | |||

| No | 32.51 ± 10.08 | 28 (80.00) | 7 (20.00) | ||

| Yes | 37.67 ± 9.08 | 36 (62.07) | 22 (37.93) | ||

| Type of pre-screening and triage center | 0.209 | 0.152 | |||

| A | 39.86 ± 13.67 | 7 (50.00) | 7 (50.00) | ||

| B | 36.51 ± 7.57 | 22 (62.86) | 13 (37.14) | ||

| C | 34.17 ± 9.35 | 18 (78.26) | 5 (21.74) | ||

| D | 33.38 ± 10.00 | 17 (80.95) | 4 (19.05) | ||

| Professional title | 0.512 | 0.311 | |||

| Junior | 36.67 ± 11.27 | 29 (63.04) | 17 (36.96) | ||

| Intermediate | 35.40 ± 7.89 | 25 (71.43) | 10 (28.57) | ||

| Senior | 33.08 ± 8.40 | 10 (83.33) | 2 (16.67) | ||

| Years of work experience | 0.613 | 0.448 | |||

| ≤3 | 35.31 ± 8.14 | 26 (72.22) | 10 (27.78) | ||

| 4–6 | 38.23 ± 16.90 | 7 (53.85) | 6 (46.15) | ||

| ≥7 | 35.34 ± 8.20 | 31 (70.45) | 13 (29.55) | ||

| Patients’ Perspective (n = 206) | |||||

| Gender | 0.315 | 0.374 | |||

| Male | 15.55 ± 5.53 | 75 (82.42) | 16 (17.58) | ||

| Female | 15.90 ± 5.02 | 89 (77.39) | 26 (22.61) | ||

| Age | 0.570 | 0.560 | |||

| ≤17 years old | 15.64 ± 5.05 | 18 (81.82) | 4 (18.18) | ||

| 18–59 years old | 15.57 ± 5.19 | 122 (80.79) | 29 (19.21) | ||

| ≥60 years old | 16.64 ± 5.63 | 24 (72.73) | 9 (27.27) | ||

| Type of pre-screening and triage center | 0.214 | 0.231 | |||

| A | 14.74 ± 4.04 | 23 (85.19) | 4 (14.81) | ||

| B | 16.21 ± 6.17 | 30 (76.92) | 9 (23.08) | ||

| C | 16.25 ± 5.43 | 81 (75.70) | 26 (24.30) | ||

| D | 14.39 ± 3.98 | 30 (90.91) | 3 (9.09) | ||

| Variables | Continuous Outcomes | Binary Outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Score | P | R | B | D | A | OR (95% CI) | |

| β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | ||

| Pre-screening triage experience | |||||||

| No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 5.63 (0.75, 10.51) | 0.45 (−0.39,1.29) | 0.37 (−0.64,1.38) | 2.35 (0.84,3.85) | 1.10 (0.41,1.80) | 2.23 (0.14,4.32) | 2.42 (0.72,8.15) |

| Type of pre-screening and triage center | |||||||

| A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| B | −2.83 (−9.13, 3.48) | −0.95 (−1.90,0.01) | −0.08 (−1.39,1.24) | −0.36 (−2.07,1.35) | −0.15 (−0.94,0.64) | −0.04 (−2.40,2.33) | 0.62 (0.16,2.42) |

| C | −4.21 (−11.15, 2.73) | −0.97 (−2.05,0.10) | −0.28 (−1.72,1.16) | −0.52 (−2.45,1.41) | −0.18 (−1.07,0.71) | −0.35 (−3.03,2.33) | 0.36 (0.07,1.72) |

| D | −5.09 (−11.82, 1.64) | −0.13 (−2.20,0.94) | 0.21 (−1.19,1.60) | −1.69 (−3.60,0.22) | −0.29 (−1.17,0.59) | −1.34 (−3.99,1.31) | 0.28 (0.06,1.35) |

| Professional title | |||||||

| Junior | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Intermediate | −1.51 (−6.31, 3.29) | −0.42 (−1.27,0.43) | −0.52 (−1.52,0.48) | −1.10 (−2.63,0.42) | −0.34 (−1.05,0.36) | −0.28 (−2.39,1.84) | 0.62 (0.21,1.86) |

| Senior | −0.28 (−8.09, 7.53) | 0.14 (−1.18,1.47) | −0.80 (−2.46,0.87) | −1.55 (−3.93,0.82) | −0.28 (−1.38,0.81) | 1.66 (−1.63,4.95) | 0.54 (0.07,4.09) |

| Years of work experience | |||||||

| ≤3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| 4–6 | 4.36 (−1.98, 10.69) | 0.81 (−0.35,1.98) | 1.28 (−0.05,2.62) | 1.15 (−0.93,3.24) | 0.23 (−0.73,1.19) | 1.71 (−1.18,4.59) | 3.06 (0.71,13.17) |

| ≥7 | 3.18 (−2.21, 8.56) | 0.58 (−0.39,1.55) | 0.94 (−0.19,2.07) | 1.47 (−0.27,3.21) | 0.19 (−0.61,0.99) | 0.92 (−1.49,3.33) | 2.26 (0.65,7.87) |

| Variables | Continuous Outcomes | Binary Outcome | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Score | Physicians | Nurses | Patients | OR (95% CI) | |

| β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Female | 0.34 (−1.12,1.80) | 0.23 (−0.33,0.80) | −0.12 (−0.62,0.38) | 0.23 (−0.30,0.75) | 1.37 (0.68,2.78) |

| Age | |||||

| ≤17 years old | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| 18–59 years old | −1.01 (−3.68,1.67) | −0.19 (−1.22,0.84) | −0.31 (−1.22,0.61) | −0.51 (−1.47,0.45) | 0.74 (0.19,2.85) |

| ≥60 years old | −0.11 (−3.33,3.11) | 0.37 (−0.88,1.61) | −0.29 (−1.39,0.81) | −0.19 (−1.34,0.97) | 1.11 (0.24,5.20) |

| Type of pre-screening and triage center | |||||

| A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| B | 1.73 (−1.12,4.57) | 0.21 (−0.89,1.31) | 1.04 (0.07,2.01) | 0.48 (−0.55,1.50) | 1.77 (0.42,7.51) |

| C | 1.75 (−0.80,4.31) | 0.26 (−0.73,1.25) | 0.84 (−0.04,1.71) | 0.66 (−0.26,1.58) | 1.90 (0.50,7.23) |

| D | −0.15 (−3.01,2.71) | −0.34 (−1.44,0.77) | 0.31 (−0.66,1.29) | −0.13 (−1.16,0.90) | 0.58 (0.11,3.13) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, S.; Zhang, L.; Du, W.; Fang, G.; Zhang, P.; Xu, F.; Hao, X.; Fan, X.; Li, A. Physician and Patient Dissatisfaction with Outpatient Pre-Screening Triage in Public Dental Hospitals: Scope and Strategies for Improvement. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1672. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141672

Ma S, Zhang L, Du W, Fang G, Zhang P, Xu F, Hao X, Fan X, Li A. Physician and Patient Dissatisfaction with Outpatient Pre-Screening Triage in Public Dental Hospitals: Scope and Strategies for Improvement. Healthcare. 2025; 13(14):1672. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141672

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Siwei, Li Zhang, Wenzhi Du, Gaofeng Fang, Peng Zhang, Fangfang Xu, Xingke Hao, Xiaojing Fan, and Ang Li. 2025. "Physician and Patient Dissatisfaction with Outpatient Pre-Screening Triage in Public Dental Hospitals: Scope and Strategies for Improvement" Healthcare 13, no. 14: 1672. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141672

APA StyleMa, S., Zhang, L., Du, W., Fang, G., Zhang, P., Xu, F., Hao, X., Fan, X., & Li, A. (2025). Physician and Patient Dissatisfaction with Outpatient Pre-Screening Triage in Public Dental Hospitals: Scope and Strategies for Improvement. Healthcare, 13(14), 1672. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141672