Loneliness and Mental Health Disorders in Older Adults Living in Portugal During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

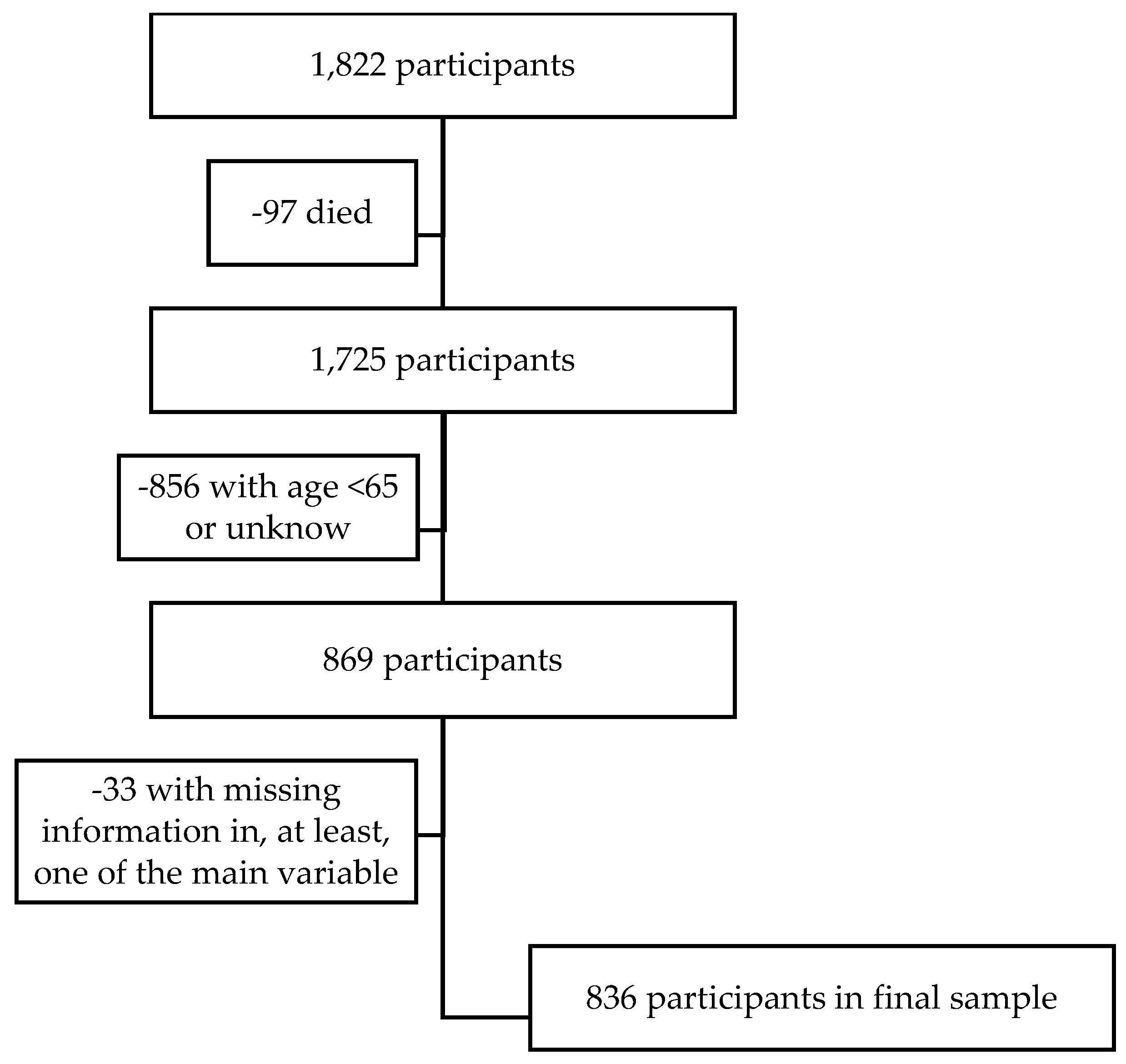

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Demography of Europe–2023 Edition. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/interactive-publications/demography-2023#population-structure (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Índice de Envelhecimento e Outros Indicadores de Envelhecimento. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/portugal/indice+de+envelhecimento+e+outros+indicadores+de+envelhecimento-526 (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Sun, X.; Li, X. Editorial: Aging and chronic disease: Public health challenge and education reform. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1175898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zadworna, M.; Ardelt, M. Understanding mental health in older adults: Exploring the interplay of wisdom, perceived poor health, and attitudes toward aging. Aging Ment. Health 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bafail, D.A. Mental health issues associated with COVID-19 among the elderly population: A narrative review. Cureus 2022, 14, e33081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodda, J.; Walker, Z.; Carter, J. Depression in older adults. BMJ 2011, 343, d5219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.J.; Hsiao, Y.H.; Liao, M.Y.; Lee, M.C. The influence of depressive mood on mortality in elderly with different health status: Evidence from the Taiwan Longitudinal Study on Aging (TLSA). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Gao, Y.; Gan, D. The combined associations of depression and cognitive impairment with functional disability and mortality in older adults: A population-based study from the NHANES 2011–2014. Front. Aging Neurosc. 2023, 15, 1121190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vink, D.; Aartsen, M.J.; Schoevers, R.A. Risk factors for anxiety and depression in the elderly: A review. J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 106, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, T.J.; Rabheru, K.; Peisah, C.; Reichman, W.; Ikeda, M. Loneliness and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1217–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, A.; Hassler, B. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on loneliness among older adults. Front. Sociol. 2020, 5, 590935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D.; Rai, M. Social isolation in Covid-19: The impact of loneliness. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnera, J.; Yuen, E.; Macpherson, H. The impact of loneliness and social isolation on cognitive aging: A narrative review. J. Alzheimers Dis. Rep. 2023, 7, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.L.; Pearce, E.; Ajnakina, O.; Johnson, S.; Lewis, G.; Mann, F.; Pitman, A.; Solmi, F.; Sommerlad, A.; Steptoe, A.; et al. The association between loneliness and depressive symptoms among adults aged 50 years and older: A 12-year population-based cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, G.N.; Ishikura, I.A.; Xavier, S.D.; Petrella, C.; Piovezan, R.D.; Xerfan, E.M.S.; Andersen, M.L.; Tufik, S. Sleep in Older Adults and Its Possible Relations with COVID-19. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 11, 647875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Tilburg, T.G.; Steinmetz, S.; Stolte, E.; van der Roest, H.; de Vries, D.H. Loneliness and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A study among Dutch older adults. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2021, 76, e249–e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolz, E.; Mayerl, H.; Freidl, W. The impact of COVID-19 restriction measures on loneliness among older adults in Austria. Eur. J. Public Health 2021, 31, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlberg, L. Loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 1161–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, S.A.; Griffith, L.E.; Oz, U.E.; Thompson, M.; Wister, A.; Kadowaki, L.; Basta, N.E.; McMillan, J.; Wolfson, C.; Raina, P. Increased prevalence of loneliness and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). BMC Public. Health 2023, 23, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börsch-Supan, A. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 8. COVID-19 Survey 1. Release Version: 8.0.0.; Data Set; SHARE-ERIC: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulia, K.K.; Kumar, V.M. Sleep disorders in the elderly: A growing challenge. Psychogeriatrics 2018, 18, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tel, H. Sleep quality and quality of life among the elderly people. Neurol. Psychiatry Brain Res. 2013, 19, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Miyamoto, M.; Hirata, K. Sleep disorders in the elderly: Diagnosis and management. J. Gen. Fam. Med. 2017, 18, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osiogo, F.; Shalaby, R.; Adegboyega, S.; Hrabok, M.; Gusnowski, A.; Vuong, W.; Surood, S.; Greenshaw, A.J.; Agyapong, V.I.O. COVID-19 pandemic: Demographic and clinical correlates of disturbed sleep among 6,041 Canadians. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2021, 25, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Qin, C.; Liu, J. Global burden of sleep disturbances among older adults and the disparities by geographical regions and pandemic periods. SSM-Popul. Health 2024, 25, 101588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R.D.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Gregório, M.J.; Branco, J.D.C.; Gouveia, M.J.; Canhão, H.; Dias, S.S. Anxiety and depression in the Portuguese older adults: Prevalence and associated factors. Front. Med. 2017, 4, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, C.; Jackson, H.; Ames, D. The prevalence of anxiety in older adults: Methodological issues and a review of the literature. J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 109, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherpenzeel, A.; Axt, K.; Bergmann, M.; Douhou, S.; Oepen, A.; Sand, G.; Schuller, K.; Stuck, S.; Wagner, M.; Börsch-Supan, A. Collecting survey data among the 50+ population during the COVID-19 outbreak: The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Surv. Res. Methods 2020, 14, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, E.J.; Jeon, H.J. The effect of COVID-19 pandemic on sleep-related problems in adults and elderly citizens: An infodemiology study using relative search volume data. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, N.; Paul, F.A.; Gul, A.; Ganie, Z.A. Loneliness and social isolation: Exploring the experiences of older women during the pandemic in terms of social connection, feeling of loneliness, and the impact on mental health and wellbeing. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2024, 5, 1410058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriques, A.; Talih, M.; Pastor-Valero, M.; Fraga, S.; Dias, I.; Matijasevich, A.; Barros, A. A multidimensional perspective of the relation between social isolation and depression among Portuguese older adults. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, C.M.; Chen, H.Y.; Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers. Soc. Psychol. ver 2011, 15, 219–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, M.A.E.G.; Saber, H.G. Long COVID and chronic fatigue syndrome: A survey of elderly female survivors in Egypt. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, E.G.; González, R.P.; Vicario-Molina, I.; Picos, A.P.; Baz, M.B.O. Loneliness and associated factors among older adults during COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2023, 86, 101547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domènech-Abella, J.; Mundó, J.; Haro, J.M.; Rubio-Valera, M. Anxiety, depression, loneliness and social network in the elderly: Longitudinal associations from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 246, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groarke, J.M.; McGlinchey, E.; McKenna-Plumley, P.E.; Berry, E.; Graham-Wisener, L.; Armour, C. Examining temporal interactions between loneliness and depressive symptoms and the mediating role of emotion regulation difficulties among UK residents during the COVID-19 lockdown: Longitudinal results from the COVID-19 psychological wellbeing study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 285, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Hawkley, L.C. Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspect. Biol. Med. 2003, 46, S39–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atıcı, E.; Girgin, N.; Çevik Saldıran, T. The effects of social isolation due to COVID-19 on the fear of movement, falling, and physical activity in older people. Australas. J. Ageing 2022, 41, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbo, I.; Forte, G.; Favieri, F.; Casagrande, M. Poor sleep quality in aging: The association with mental health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lage, I.; Braga, F.; Almendra, M.; Meneses, F.; Teixeira, L.; Araújo, O. Older people living alone: A predictive model of fall risk. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeytinoglu, M.; Wroblewski, K.E.; Vokes, T.J.; Huisingh-Scheetz, M.; Hawkley, L.C.; Huang, E.S. Association of loneliness with falls: A study of older US adults using the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 7, 2333721421989217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, B.; Costa, D.; Xavier, J.; Viveiro, L.; Antunes, T.; Mendes, F.; Oliveira, M.A.K.; Bomfim, C.P.; Hsien, K.S.; Silva, E.C.G.; et al. Social isolation due to COVID-19: Impact on loneliness, sedentary behavior, and falls in older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2022, 26, 2120–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengarini, E.; Ruggiero, C.; Pérez-Zepeda, M.U.; Hoogendijk, E.O.; Vellas, B.; Mecocci, P.; Cesari, M. Fatigue: Relevance and implications in the aging population. Exp. Gerontol. 2015, 70, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okruszek, L.; Aniszewska-Stańczuk, A.; Piejka, A.; Wiśniewska, M.; Żurek, K. Safe but lonely? Loneliness, anxiety, and depression symptoms and COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 579181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocuzzo, B.; Wrench, A.; O’Malley, C. Effects of COVID-19 on older adults: Physical, mental, emotional, social, and financial problems seen and unseen. Cureus 2022, 14, e29493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kok, A.A.L.; Huisman, M.; Giltay, E.J.; Lunansky, G. Adopting a complex systems approach to functional ageing: Bridging the gap between gerontological theory and empirical research. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2025, 6, 100673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender [male] | 387 (46.3) |

| Age, mean (sd 1) [min–max] | 74.5 (6.7) [65–97] |

| How was your health before the outbreak? | |

| Excellent | 17 (2.0) |

| Very good | 39 (4.6) |

| Good | 265 (31.7) |

| Fair | 350 (41.9) |

| Poor | 165 (19.7) |

| Change in your health since the outbreak | |

| Improved | 21 (2.5) |

| Worsened | 106 (12.7) |

| About the same | 709 (84.8) |

| Diagnosed with a major health condition [yes] | 163 (19.5) |

| Falling more often [yes] | 136 (16.3) |

| Fear of falling [yes] | 336 (40.2) |

| Dizziness, fainting, or blackouts [yes] | 238 (28.5) |

| Fatigue [yes] | 402 (48.1) |

| Takes prescription drugs regularly [yes] | 768 (91.9) |

| Felt nervous [yes] | 435 (52.0) |

| Sad or depressed [yes] | 378 (45.2) |

| Trouble sleeping recently [yes] | 346 (41.4) |

| How often do you feel lonely [often or some of the time] | 279 (33.4) |

| Feeling Lonely | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Often or Some of the Time | Hardly Never or Never | p | |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Gender [male] | 95 (34.1) | 292 (52.4) | <0.001 |

| Age, mean (sd 1) | 74.9 (6.8) | 74.4 (6.7) | 0.238 2 |

| How was your health before the outbreak? | <0.001 | ||

| Excellent | 4 (1.4) | 13 (2.3) | |

| Very good | 8 (2.9) | 31 (5.6) | |

| Good | 64 (22.9) | 201 (36.1) | |

| Fair | 129 (46.2) | 221 (39.7) | |

| Poor | 74 (26.5) | 91 (16.3) | |

| Change in your health since the outbreak | <0.001 | ||

| Improved | 6 (2.2) | 16 (2.8) | |

| Worsened | 61 (21.9) | 46 (8.1) | |

| About the same | 212 (76.0) | 505 (89.1) | |

| Diagnosed with a major health condition [yes] | 65 (23.3) | 98 (17.6) | 0.050 |

| Falling more often [yes] | 53 (19.0) | 83 (14.9) | 0.130 |

| Fear of falling [yes] | 135 (48.4) | 201 (36.1) | <0.001 |

| Dizziness, fainting, or blackouts [yes] | 93 (33.3) | 145 (26.0) | 0.027 |

| Fatigue [yes] | 168 (60.2) | 234 (42.0) | <0.001 |

| Takes prescription drugs regularly [yes] | 260 (93.2) | 508 (91.2) | 0.322 |

| Feeling nervous [yes] | 202 (72.4) | 233 (41.8) | <0.001 |

| Sad or depressed [yes] | 197 (70.6) | 181 (32.5) | <0.001 |

| Trouble sleeping recently [yes] | 153 (54.8) | 193 (34.6) | <0.001 |

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR 1 | 95% CI 2 | p | OR 1 | 95% CI 2 | p | |

| Gender [female] | 2.803 | 2.116–3.712 | <0.001 | 2.084 | 1.538–2.824 | <0.001 |

| Age (z-score) | 0.941 | 0.821–1.077 | 0.377 | 0.835 | 0.715–0.974 | 0.022 |

| Diagnosed with a major health condition [yes] | 1.503 | 1.061–2.129 | 0.022 | 1.297 | 0.883–1.906 | 0.185 |

| Fatigue [yes] | 2.766 | 2.089–3.662 | <0.001 | 2.205 | 1.612–3.017 | <0.001 |

| Trouble sleeping recently [yes] | 2.877 | 2.159–3.835 | <0.001 | 1.989 | 1.456–2.717 | <0.001 |

| How often do you feel lonely [often or some of the time]? | 3.648 | 2.671–4.983 | <0.001 | 2.803 | 2.011–3.908 | <0.001 |

| R2 (Cox And Snell) | 0.179 | |||||

| R2 (Nagelkerke) | 0.239 | |||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR 1 | 95% CI 2 | p | OR 1 | 95% CI 2 | p | |

| Gender [female] | 2.943 | 2.213–3.912 | <0.001 | 2.102 | 1.530–2.887 | <0.001 |

| Age (z-score) | 1.107 | 0.966–1.269 | 0.144 | 1.031 | 0.879–1.209 | 0.709 |

| Diagnosed with a major health condition [yes] | 1.925 | 1.361–2.724 | 0.022 | 1.747 | 1.177–2.593 | 0.006 |

| Fatigue [yes] | 2.805 | 2.117–3.717 | <0.001 | 1.918 | 1.389–2.648 | <0.001 |

| Trouble sleeping recently [yes] | 3.590 | 2.689–4.793 | <0.001 | 2.636 | 1.914–3.630 | <0.001 |

| How often do you feel lonely [often or some of the time]? | 4.991 | 3.651–6.823 | <0.001 | 3.878 | 2.772–5.424 | <0.001 |

| R2 (Cox And Snell) | 0.230 | |||||

| R2 (Nagelkerke) | 0.308 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Araújo, O.; Sousa, L.; Sampaio, F.; Rodrigues, C.; Santos, N.C.; Sequeira, C.; Teixeira, L. Loneliness and Mental Health Disorders in Older Adults Living in Portugal During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1483. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131483

Araújo O, Sousa L, Sampaio F, Rodrigues C, Santos NC, Sequeira C, Teixeira L. Loneliness and Mental Health Disorders in Older Adults Living in Portugal During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(13):1483. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131483

Chicago/Turabian StyleAraújo, Odete, Lia Sousa, Francisco Sampaio, Cláudia Rodrigues, Nadine Correia Santos, Carlos Sequeira, and Laetitia Teixeira. 2025. "Loneliness and Mental Health Disorders in Older Adults Living in Portugal During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 13, no. 13: 1483. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131483

APA StyleAraújo, O., Sousa, L., Sampaio, F., Rodrigues, C., Santos, N. C., Sequeira, C., & Teixeira, L. (2025). Loneliness and Mental Health Disorders in Older Adults Living in Portugal During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 13(13), 1483. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131483