Digitalization in Dentistry: Dentists’ Perceptions of Digital Stressors and Resources and Their Association with Digital Stress in Germany—A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Techno-complexity: Difficulty mastering complex tools requiring continuous learning [12];

- Techno-uncertainty: Stress from rapid technological changes undermining confidence [13];

- Techno-insecurity: Fear of job loss due to automation [13];

- Techno-invasion: Blurred boundaries between work and personal life due to constant connectivity [13].

- What are the positive and negative experiences of dentists in using digital assistance systems in clinical practice?This question focuses on the individual experiences of dentists, highlighting both the advantages and difficulties they have encountered through digital transformation in their daily work.

- How does the perceived usefulness, intuitiveness, and ease of use of digital technologies influence the level of techno-stress experienced by dentists?This question examines how usability factors affect stress levels and overall acceptance of digital tools.

- What specific techno-stressors and techno-stress inhibitors are associated with the digitalization of dental practice?This question identifies key stress-inducing and stress-reducing factors within digital dental environments.

- What training formats and support measures do dental professionals consider necessary for effectively integrating digital technologies into practice?This question investigates preferred learning methods and support needs for successful and sustainable digital adoption.

- What strategies are required to ensure a sustainable, ethically sound, and health-conscious implementation of digital technologies in dentistry?This question focuses on organizational, policy-level, and ethical aspects that support long-term, responsible digital transformation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participant Selection, Inclusion Criteria, and Setting

2.3. Data Collection

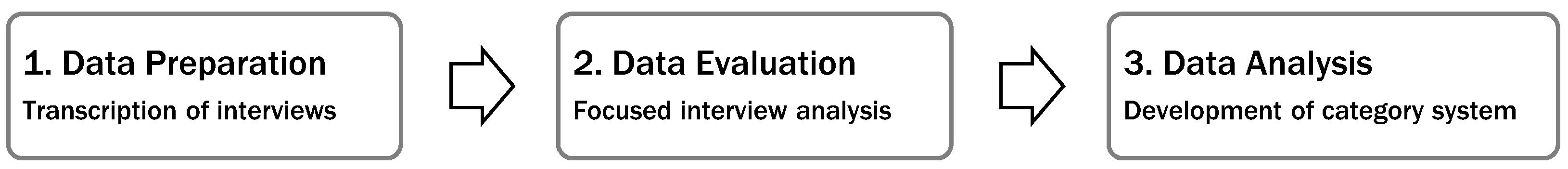

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Occupational Characteristics of the Study Participants

3.2. Representation of the Use of Digital Assistance Systems

3.3. Experiences with Digital Assistance Systems in Dentistry: A Practice-Based Evaluation

3.3.1. Negative Experiences in the Use of Digital Assistance Systems

- 1.

- General Systemic Challenges: Overload, Instability, and Digital Competency

“There are always things that don’t work, and it can be frustrating when something doesn’t function as it should. It often takes a long time to find the solution.”(Participant 7, female, age 30–39)

- 2.

- CAD/CAM and Chairside Systems: Efficiency vs. Precision

“It’s not really a time saver. A gold crown still fits best, but that also depends on the material.”(Participant 7, female, age 30–39)

“The computer program was too precise. I had to grind down the teeth quite a lot for the system to recognize the parallelism. A handheld device acknowledges this much sooner and still gets good results.”(Participant 7, female, age 30–39)

- 3.

- Intraoral Scanners: Limited Applicability and User Dependency

“My crowns were also, at the beginning, influenced by the preparation, where you first have to get used to the device and figure out what it really needs for the scan and the calculation.”(Participant 7, female, age 30–39)

“This really only works for patients who do not have gingivitis or where you are not preparing subgingivally. As soon as there is bleeding, it becomes significantly more difficult to scan everything accurately.”(Participant 2, female, age 20–29)

- 4.

- Telematics Infrastructure: High Costs and Low Reliability

“Exactly, it doesn’t work. The technology isn’t fully developed. This router brings constant costs that you don’t want to cover because, honestly, you don’t even want to have it in the first place.”(Participant 9, female, age 50–59)

- 5.

- Practice Management Software: Technical Failures and Data Access

“We had disruptions in the server for three days. We didn’t know which patients were coming. We couldn’t input any services. We didn’t know what treatments had taken place before. Nothing was visible in the computer.”(Participant 10, female, age 50–59)

- 6.

- Implant Planning Software: Visualization and Placement Challenges

“In the area of the implant shoulder, there have been cases where it ended up protruding by about a millimeter. Then I couldn’t set it in bone-stable placement. Sometimes, seeing the end of the bone structure can be difficult.”(Participant 7, female, age 30–39)

- 7.

- Digital Volume Tomography (DVT): Unequal Access

“It’s just another tool that can easily be used with private patients, but with statutory health insurance, there’s always the question of whether patients want to invest in it. It just depends on their income.”(Participant 8, female, age 20–29)

3.3.2. Positive Experiences in the Use of Digital Assistance Systems

- 1.

- Overall Perceptions: When Systems Work, They Work Well

“Fundamentally, this applies to everything: if it works, it’s excellent. If it doesn’t, it leads to frustration.”(Participant 5, male, age 30–39)

- 2.

- CAD/CAM and Chairside Systems: Aesthetic Quality and Efficiency

“The good thing is that you can actually complete a complex task within a single session.”(Participant 4, female, age 30–39)

- 3.

- Intraoral Scanners: Versatility and Improved Patient Comfort

“Things like that [gag reflex], where patients simply have aversions, especially to an impression. That’s very advantageous.”(Participant 3, male, age 50–59)

“But everything you can do with scanners is huge. Also what the lab can do with the dataset. You no longer have to keep the models; you can use them digitally right away. That’s just enormous.”(Participant 9, female, age 50–59)

- 4.

- Digital Volume Tomography (DVT): Diagnostic Clarity and Surgical Precision

“Yes, it is certainly safer. You don’t just have the two-dimensional image to rely on. This means that the maxillary sinus or nerve is surely there where you can see it in the image.”(Participant 7, female, age 30–39)

- 5.

- Digital X-Ray Systems: Speed, Communication, and Clinical Integration

“Digitally, you have it right away. If there’s any doubt, you can quickly call the referring doctor while the patient is still there and say you need the X-ray. So that’s a huge advantage.”(Participant 1, male, age 30–39)

“I think that’s quite good as well, especially when you want to measure the length again during an endo treatment or see what the root looks like.”(Participant 2, female, age 20–29)

- 6.

- Practice Management Software: Organization, Documentation, and Transparency

“It also creates good documentation and provides security that working hours are recorded clearly and accurately.”(Participant 3, male, age 50–59)

“You can get things done more quickly, and you’re more organized than if you had everything on paper and were carrying around a stack of files. You’re more flexible, which I like.”(Participant 2, female, age 20–29)

- 7.

- Communication Tools: Flexibility and Real-Time Coordination

“We are using Microsoft Teams as a team communication tool. This allows you to reach any employee from anywhere in the practice at any time of day.”(Participant 5, male, age 30–39)

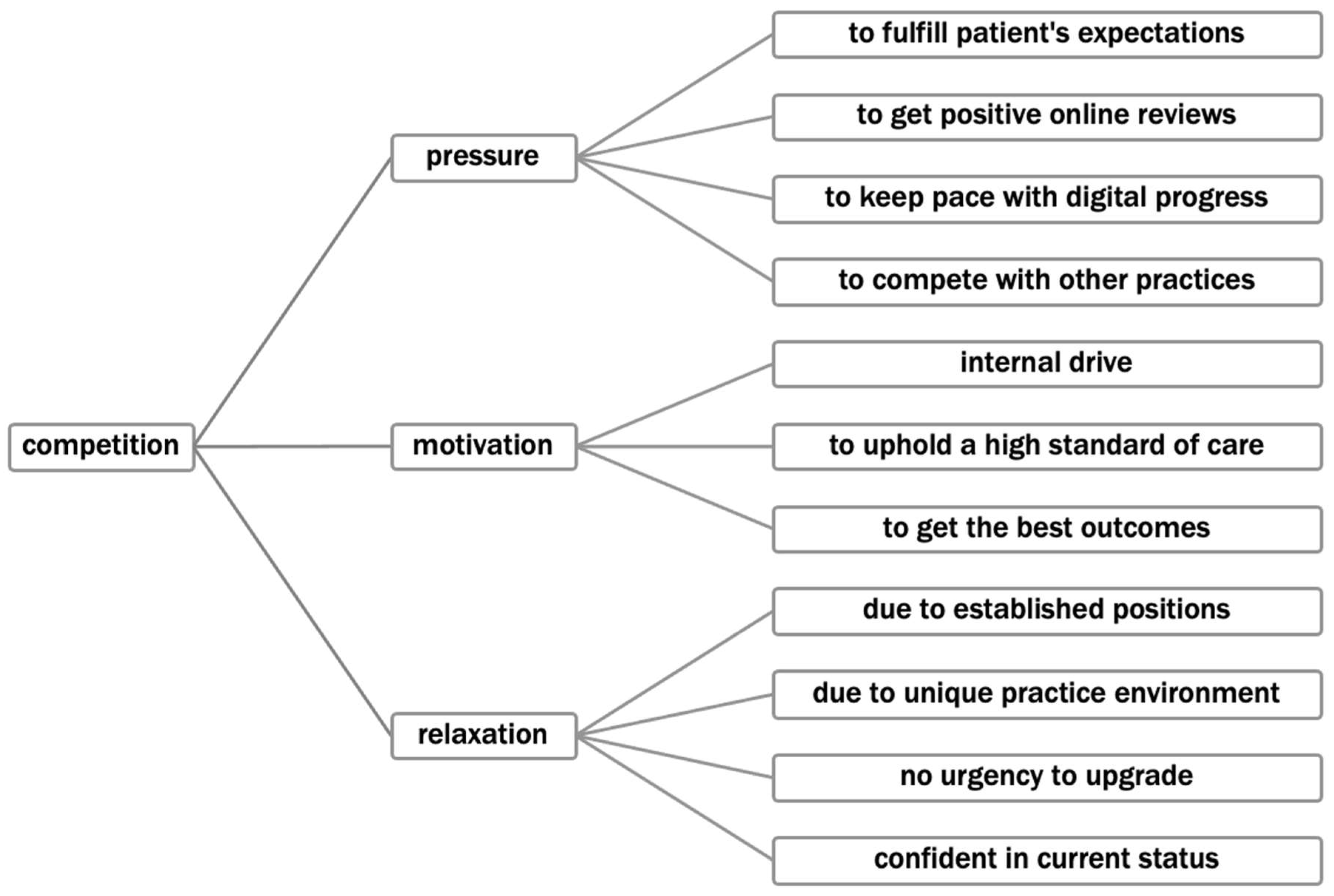

3.4. Stress-Inducing Factors: Competitive Pressures and Strategic Adaptions in the Context of Digital Transformation

“Those who do not advance digitalization in their dental practices will face low patient numbers. These practices will not have motivated employees, and, in the long term, they will be at a clear competitive disadvantage. Such practices will ultimately have to close.”(Participant 5, male, age 30–39)

“People spread the word quickly, saying that only certain doctors had this device and that it worked so much faster. So, external pressure builds up, making you feel like you have to keep up with progress.”(Participant 1, male, age 30–39)

“I wouldn’t describe it as negative pressure. In the end, it makes sense. The things being developed are intended for improvement. Especially in diagnostics and workflow acceleration, it’s a good kind of pressure.”(Participant 6, female, age 20–29)

“I actually don’t know any practice that’s better equipped. And that makes me feel incredibly relaxed about this topic every day.”(Participant 5, male, age 30–39)

3.5. Ethical Challenges in the Use of Digital Assistance Systems in Dental Practices

3.5.1. Responsibility and Error Attribution in Digital Workflows

“No, I know that it ultimately falls on me. I’m the one who was behind the scenes making the preparations. The computer doesn’t make mistakes in that sense; any errors stem from my work.”(Participant 7, female, age 30–39)

“It’s much easier to correct a mistake. For example, if a tooth isn’t scanned correctly, you can just delete that part and redo it without ruining the entire impression.”(Participant 9, female, age 50–59)

“When more errors creep in, it becomes much more anonymous. It’s harder for the team to identify whether the error occurred at reception, in the treatment room, or with the practitioner.”(Participant 8, female, age 20–29)

3.5.2. Broader Ethical Implications: Data Protection, Over-Treatment, and Depersonalization

“We have semi-annual consent forms that patients must sign. Additionally, one must ensure that incoming patients don’t see the X-rays of the previous patient on the screen.”(Participant 8, female, age 20–29)

“There might be a tendency to treat people much sooner because we can identify issues more readily in imaging. I believe we need to find a good balance here.”(Participant 1, male, age 30–39)

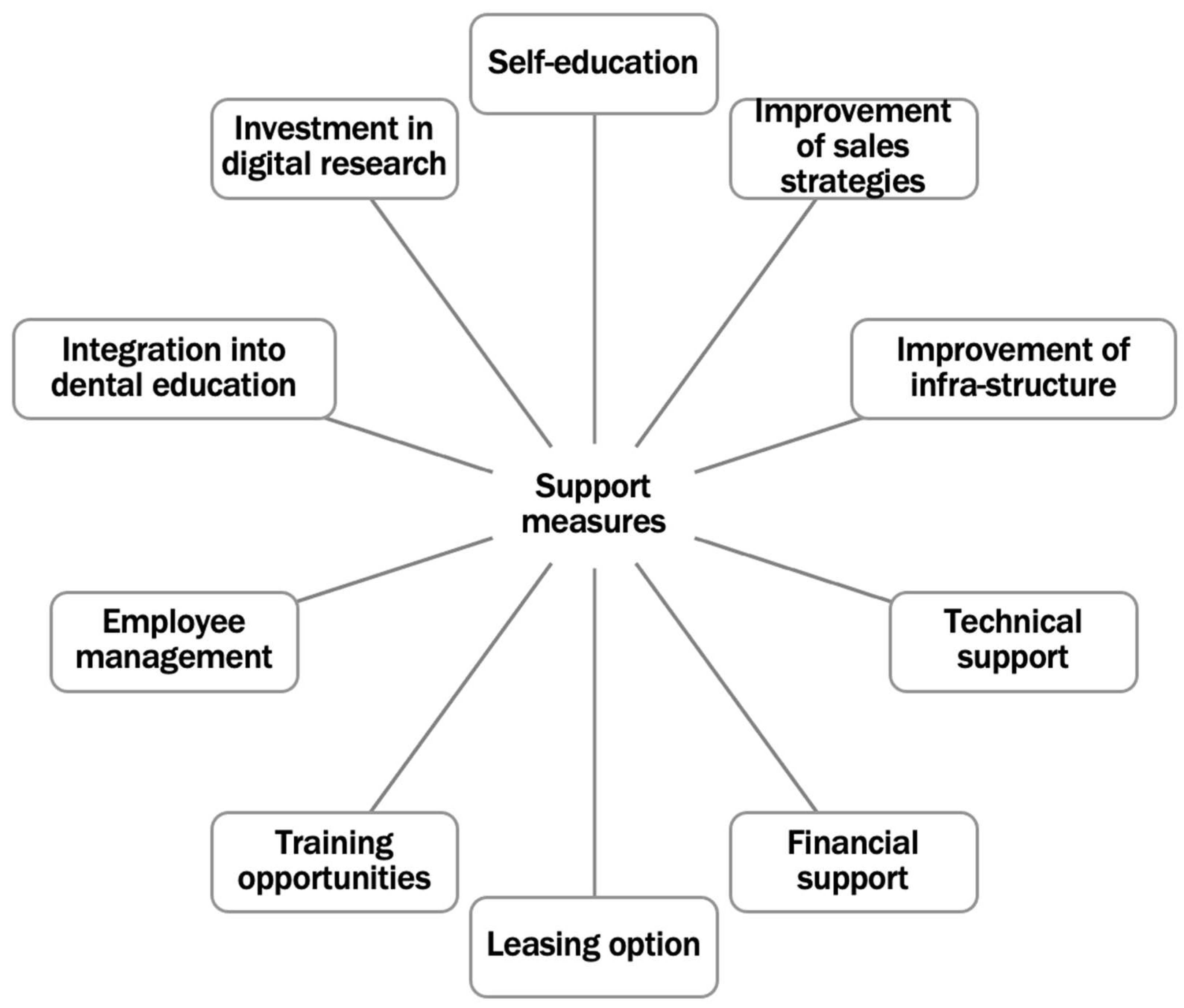

3.6. Support Needs and Learning Methods for Successful Digital Adoption

3.6.1. User-Friendliness and Application Support

“It should not be a technical gimmick. We are not specialists in usability. This is not a pastime in the practice; providing care for patients is our goal.”(Participant 10, female, age 50–59)

“I would certainly like to see the systems working more integratively with each other. The software interfaces should become more open.”(Participant 5, male, age 30–39)

3.6.2. Willingness to Learn and Age-Related Differences

“I’m happy to embrace what is proven, scientifically validated. What companies throw on the market that isn’t backed by research, I prefer to stay away from.”(Participant 8, female, age 20–29)

“Digital work motivates me. I’m definitely willing to acquire new skills to make the most of the technical possibilities.”(Participant 5, male, age 30–39)

3.6.3. Support Measures for Sustainable Digital Implementation

“I have to educate myself. If I’m interested in a topic, I can find information, but I have to work through it all on my own.”(Participant 7, female, age 30–39)

“Digitalization hasn’t progressed much because the necessary conditions simply aren’t in place. There are quite a few prerequisites that need to be met.”(Participant 2, female, age 20–29)

“If the government mandates certain technologies, they also need to support practices financially. Not every practice can afford such upgrades.”(Participant 2, female, age 20–29)

“Leasing is a good solution because technology evolves so quickly. Buying a device often locks you into outdated technology.”(Participant 10, female, age 50–59)

“It’s simply a matter of employee management. You need to know which staff members are digitally literate and tailor the training accordingly.”(Participant 5, male, age 30–39)

“I believe dentistry is weak in scientific research. I would appreciate it if universities invested more in digital advancement.”(Participant 8, female, age 20–29)

4. Discussion

4.1. Dentists’ Experiences with Digital Assistance Systems: Usage Behavior and Subjective Evaluation in Clinical Practice

4.2. Technology-Associated Stressors and Resources

4.3. Ethical Challenges for Dentists in the Use of Digital Assistance Systems

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

4.5. Implications for Further Research

4.6. Implications for Practice, Policy, and Dental Education

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MAXQDA | Max Weber Qualitative Data Analysis |

| COREQ | Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research |

| CAD/CAM | Computer-aided design/Computer-aided manufacturing |

| IT | Information Technology |

| LPEK | Local Psychological Ethics Committee |

| CMD | Cranio-mandibular dysfunction |

| DVT | Digital volume technology |

| TMJ | Temporo-mandibular joint |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

References

- Neuhaus, A.; Lechleiter, P.; Sonntag, K. Measures and Recommendations for Healthy Work Practices of Tomorrow (MEgA); Friedrich-Alexander-Universität: Erlangen, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Odone, A.; Buttigieg, S.; Ricciardi, W.; Azzopardi-Muscat, N.; Staines, A. Public Health Digitalization in Europe: EUPHA Vision, Action and Role in Digital Public Health. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rekow, E.D. Digital Dentistry: The New State of the Art—Is It Disruptive or Destructive? Dent. Mater. 2020, 36, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brod, C. Managing Technostress: Optimizing the Use of Computer Technology. Pers. J. 1982, 61, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ragu-Nathan, T.; Tarafdar, M.; Ragu-Nathan, B.; Ragu-Nathan, T.; Ragu-Nathan, Q. The Consequences of Technostress for End Users in Organizations: Conceptual Development and Empirical Validation. Inf. Syst. Res. 2008, 19, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafdar, M.; Cooper, C.; Stich, J. The Technostress Trifecta-techno Eustress, Techno Distress and Design: Theoretical Directions and an Agenda for Research. Inf. Syst. J. 2019, 29, 6–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafdar, M.; Tu, Q.; Ragu-Nathan, B.; Ragu-Nathan, T. The Impact of Technostress on Role Stress and Productivity. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007, 24, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golz, C.; Peter, K.A.; Zwakhalen, S.M.G.; Hahn, S. Technostress Among Health Professionals—A Multilevel Model and Group Comparisons between Settings and Professions. Inform. Health Soc. Care 2021, 46, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raišienė, A.G.; Jonušauskas, S. Silent Issues of ICT Era: Impact of Techno-Stress to the Work and Life Balance of Employees. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2013, 1, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuglseth, A.M.; Sørebø, Ø. The Effects of Technostress within the Context of Employee Use of ICT. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 40, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondanini, G.; Giorgi, G.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Andreucci-Annunziata, P. Technostress Dark Side of Technology in the Workplace: A Scientometric Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 8013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Llorens, S.; Cifre, E. The Dark Side of Technologies: Technostress among Users of Information and Communication Technologies. Int. J. Psychol. 2013, 48, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mark, G.; Gudith, D.; Klocke, U. The Cost of Interrupted Work: More Speed and Stress. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 107–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gimpel, H.; Lanzl, J.; Manner-Romberg, T.; Nüske, N. Digitaler Stress in Deutschland: Eine Befragung von Erwerbstätigen Zu Belastung Und Beanspruchung Durch Arbeit Mit Digitalen Technologien. Hans-Böckler-Stift. 2018, 101, 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Tajirian, T.; Stergiopoulos, V.; Strudwick, G.; Sequeira, L.; Sanches, M.; Kemp, J.; Ramamoorthi, K.; Zhang, T.; Jankowicz, D. The Influence of Electronic Health Record Use on Physician Burnout: Cross-Sectional Survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahr, T.J.; Ginsburg, S.; Wright, J.G.; Shachak, A. Technostress as Source of Physician Burnout: An Exploration of the Associations between Technology Usage and Physician Burnout. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2023, 177, 105147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragano, N.; Lunau, T. Technostress at Work and Mental Health: Concepts and Research Results. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2020, 33, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernburg, M.; Gebhardt, J.S.; Groneberg, D.A.; Mache, S. Impact of Digitalization in Dentistry on Technostress, Mental Health, and Job Satisfaction: A Quantitative Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrucci, M.; Wortz, M. Sampling Und Stichprobe. In QUASUS Qualitatives Methodenportal zur Qualitativen Sozial-, Unterrichts-und Schulforschung; Universität Freiburg: Freiburg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkens, H. Stichproben Bei Qualitativen Studien. In Handbuch Qualitative Forschungsmethoden in der Erziehungswissenschaft; Friebertshäuser, B., Prengel, A., Eds.; Juventa: Weinheim, Germany; München, Germany, 1997; pp. 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4833-1568-3. [Google Scholar]

- Helfferich, C. Leitfaden- Und Experteninterviews. In Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung; Baur, N., Blasius, J., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 669–686. ISBN 978-3-658-21308-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bogner, A.; Littig, B.; Menz, W. Interviews Mit Experten Eine Praxisorientierte Einführung; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014; ISBN 978-3-531-19415-8. [Google Scholar]

- Meuser, M.; Nagel, U. Qualitativ-Empirische Sozialforschung: Konzepte, Methoden, Analysen. In Expert Inneninterviews—Vielfach Erprobt, Wenig Bedacht: Ein Beitrag zur Qualitativen Methodendiskussion; Garz, D., Kraimer, K., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschafte: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1991; ISBN 3-531-12289-4. [Google Scholar]

- Helfferich, C. Die Qualität Qualitativer Daten. Manual Für Die Durchführung Qualitativer Interviews, 4th ed.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011; ISBN 978-3-531-17382-5. [Google Scholar]

- Witzel, A. Das Problemzentrierte Interview. In Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie; Jüttemann, G., Ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany; Basel, Switzerland, 1985; pp. 227–255. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz, U.; Rädiker, S. Fokussierte Interviewanalyse Mit MAXQDA Schritt Für Schritt, 1st ed.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2021; ISBN 978-3-658-31467-5. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. In Qualitative Forschung. Ein Handbuch; Flick, U., von Kardoff, E., Steinke, I., Eds.; Rowohlt Taschenbuch: Hamburg, Germany, 2012; pp. 468–474. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen Und Techniken, 12th ed.; Beltz Verlag: Weinheim, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Golz, C.; Peter, K.A.; Müller, T.J.; Mutschler, J.; Zwakhalen, S.M.; Hahn, S. Technostress and Digital Competence among Health Professionals in Swiss Psychiatric Hospitals: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e31408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaresani, A.; Scott, A. Does Digital Health Technology Improve Physicians’ Job Satisfaction and Work–Life Balance? A Cross-Sectional National Survey and Regression Analysis Using an Instrumental Variable. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e041690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, E.; Vallejos, E.; Spence, A. The Digital Workplace and Its Dark Side: An Integrative Review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 128, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zande, M.; Gorter, R.; Aartman, I.; Wismeijer, D. Adoption and Use of Digital Technologies among General Dental Practitioners in the Netherlands. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafarpour, D.; Haricharan, P.B.; de Souza, R.F. CAD/CAM versus Traditional Complete Dentures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Patient- and Clinician-Reported Outcomes and Costs. J. Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 1911–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pullishery, F.; Huraib, W.; Alruhaymi, A. Intraoral Scan Accuracy and Time Efficiency in Implant-Supported Fixed Partial Dentures: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e48027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengel, R.; Candir, M.; Shiratori, K.; Flores-de-Jacoby, L. Digital Volume Tomography in the Diagnosis of Periodontal Defects: An in Vitro Study on Native Pig and Human Mandibles. J. Periodontol. 2005, 76, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Rehouma, M.; Geyer, T.; Kahl, T. Investigating Change Management Based on Participation and Acceptance of IT in the Public Sector: A Mixed Research Study. Int. J. Public Adm. Digit. Age 2020, 7, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cheng, T.; Cheng, C. Exploring the Factors That Influence Physician Technostress from Using Mobile Electronic Medical Record. Inf. Health Soc. Care 2019, 44, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heponiemi, T.; Kujala, S.; Vainiomäki, S.; Vehko, T.; Lääveri, T.; Vänskä, J.; Ketola, E.; Puttonen, S.; Hyppönen, H. Usability Factors Associated With Physician’s Distress and Information System-Related Stress: Cross-Sectional Survey. JMIR Med. Inf. 2019, 7, e13466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuek, A.; Hakkennes, S. Healthcare Staff Digital Literacy Levels and Their Attitudes towards Information. Health Inform. J. 2020, 26, 592–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimpel, H.; Lanzl, J.; Regal, C. Gesund Digital Arbeiten?! In Eine Studie Zu Digitalem Stress in Deutschland; Fraunhofer-Institut Für Angewandte Informationstechnik FIT: Augsburg, Germany; Bundesanstalt Für Arbeitsschutz Und Arbeitsmedizin, MF/M-Bayreuth: Dortmund, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sommovigo, V.; Bernuzzi, C.; Finstad, G.L.; Setti, I.; Gabanelli, P.; Giorgi, G.; Fiabane, E. How and When May Technostress Impact Workers’ Psycho-Physical Health and Work-Family Interface? A Study during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretherton, R.; Chaoman, H.; Chipchase, S. A Study to Explore Specific Stressors and Coping Strategies in Primary Dental Care Practice. Br. Dent. J. 2016, 220, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; Maglaras, L.; Ferrag, M.; Almomani, I. Digitization of Healthcare Sector: A Study on Privacy and Security Concerns. ICT Express 2023, 9, 571–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toon, M.; Collin, V.; Whitehead, P.; Reynolds, L. An Analysis of Stress and Burnout in UK General Dental Practitioners: Subdimensions and Causes. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 226, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topic | Category | Subcategory |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Sociodemographic and occupational characteristics of the participants | Practice-specific information data | Practice setup |

| Dental laboratory | ||

| Person-specific information | Specialization/treatment spectrum | |

| Work schedule | ||

| Professional career | ||

| Employment contract | ||

| Daily work routine | ||

| Age | ||

| Level of education | ||

| 2: Use and use evaluation of digital assistance systems in dental practices | Usage behavior | Digital assistance systems that are used |

| Usage behavior | ||

| Frequency of use | ||

| Subjective evaluation of use | Positive experience reports | |

| Negative experience reports | ||

| 3: Ethical challenges of the use of digital assistance systems in dental practices | Ethical challenges | Responsibility |

| Dealing with errors | ||

| Ethical questions | ||

| 4: Support needs and opportunities in digital dentistry | Needs assessment | Support measures |

| Willingness to learn | ||

| Support, maintenance | ||

| User-friendliness of digital tools |

| Theme | Subtheme |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic and occupational characteristics of the participants | |

| Use and use evaluation of digital assistance systems | Representation of the use of digital assistance systems Experiences with digital assistance systems: A practice-based evaluation

|

| Stress-inducing factors | Competitive pressures and strategic adaptations |

| Ethical challenges in the use of digital assistance systems | Responsibility and error attribution in digital workflows Broader ethical implications: data protection, over-treatment, and depersonalization |

| Support needs and learning methods for successful digital adoption | User-friendliness and application support Willingness to learn and age-related differences Support measures for sustainable digital implementation |

| Category | Characteristic | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 6 | 60 |

| Male | 4 | 40 | |

| Age | 20–29 | 3 | 30 |

| 30–39 | 4 | 40 | |

| 40–49 | 0 | 0 | |

| 50–59 | 3 | 30 | |

| Position | Assistant dentist | 2 | 20 |

| Employed dentist | 3 | 30 | |

| Practice owner | 5 | 50 | |

| Profession | Approbation | 2 | 20 |

| Promotion | 8 | 80 | |

| Years of work experience | 1–9 | 4 | 40 |

| 10–19 | 3 | 30 | |

| 20–29 | 2 | 20 | |

| 30–39 | 1 | 10 | |

| Working pensum (%) | 0–19 | 0 | 0 |

| 20–39 | 0 | 0 | |

| 40–59 | 1 | 10 | |

| 60–79 | 0 | 0 | |

| 80–100 | 9 | 90 | |

| (Practice-)Specialization | Implantology/dental surgery | 2 | 20 |

| Cranio-mandibular dysfunction (CMD)/ functional diagnostics | 2 | 20 | |

| Endodontics/parodontology | 2 | 20 | |

| General | 4 | 40 |

| Digital Tool | Application |

|---|---|

| Intraoral scanner | Fabrication of prosthetic restorations, e.g., crowns, interim splints (especially posterior region, all zirconia), and splints Implant work (abutments, crowns, and surgical guiding templates) Documentation for research, e.g., volume change |

| Digital X-ray | Endodontics, caries diagnostics, and periodontology |

| Intraoral camera | Visualization of dental plaque, caries, and tooth fractures (diagnosis and patient communication) |

| Model scanners | Scanning plaster models (prosthetics) |

| DVT | Pre-surgical baseline assessment (wisdom tooth extraction and cyst exposures) and implant planning |

| Practice management software | Staff management, communication, quality control (efficient operations) |

| Online training tools | Continuous professional development (accessible ongoing training) |

| Patient education software | Treatment plan and consent form signing (enhancing patient interaction) |

| CAD/CAM technologies | Planning and production of dental prostheses (skill-dependent outcomes) |

| Digital facebows | Recording and evaluating temporo-mandibular joint (TMJ) trajectories (precise prosthetic design) |

| 3D printers | Producing dental models (streamlined fabrication and improved efficiency) |

| Negative Experiences | Details |

|---|---|

| Technical problems | Malfunctions, handling difficulties |

| Extensive error analysis | |

| Unstable networks | |

| Risk of cyber-attacks | |

| Poorly suited IT infrastructure | |

| Low user friendliness | Reliant on the user’s experience |

| Systems’ potential not fully realized | |

| Non-intuitive workflows | |

| Lack of interoperability between different digital systems | |

| Clinical documentation | High traceability and controllability |

| Increased workload | Strict data protection measures |

| Need for additional analog safeguards | |

| System monitoring/controlling | |

| Staff training | |

| Transition process | |

| Training | Insufficient training for staff |

| Digital transformation | Further complications due to the transition process |

| Undefined areas of responsibilities | |

| Costs | High substantial expenses for acquisition, maintenance, research and development |

| Rapid obsolescence of older devices, necessitating new purchases, increasing financial burdens | |

| Results | Inaccuracy of results in some cases |

| Limited indications | |

| High substance removal |

| Positive Experiences | Details |

|---|---|

| Availability of information | Enhancement of the availability of information Quick and simultaneous accessibility to patient data across all computers |

| General reduction of workload and time-savings | Improved communication with dental labs and staff Immediate use of data sets No need for physical storage and archiving Easier delegation of tasks Standardization of procedures Increased efficiency and safety for practitioners Comfortable handling Good integration of the software into existing workflows |

| Transparency | Better readability and a more comprehensive overview of patient data Ensuring transparent documentation Easy comparability of records Enhancement of the accuracy and clarity of information |

| Results | High aesthetic outcomes, particularly in prosthetics Excellent visualization of structures, e.g., through DVT images Wide range of indications Minimization of contamination risks by reducing the need for paper records |

| IT support | Technical support available from software companies |

| Patients | More comfortable experience during treatments Positive impact on communication between the dentist and the patient Fostering better understanding and trust |

| Techno-Stressors | Causes |

|---|---|

| Techno-overload | Management of multiple tasks at the same time |

| Own claim to work faster and more efficiently | |

| Competitive pressure | |

| Rapid technological developments | |

| Techno-uncertainty | Lack of digital skills |

| Familiarization with digital work processes | |

| System instability | |

| Techno-complexity | Complex, non-intuitive digital work processes |

| Software errors, equipment failures, technical problems | |

| Time-consuming troubleshooting | |

| Lack of technical support | |

| Dependency on technology | |

| Techno-insecurity | Risk of inadequate data protection/higher data protection regulations |

| Risk of over-treatment | |

| Techno-invasion | Loss of control or responsibility |

| Reduction of personalization |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gebhardt, J.S.; Harth, V.; Groneberg, D.A.; Mache, S. Digitalization in Dentistry: Dentists’ Perceptions of Digital Stressors and Resources and Their Association with Digital Stress in Germany—A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121453

Gebhardt JS, Harth V, Groneberg DA, Mache S. Digitalization in Dentistry: Dentists’ Perceptions of Digital Stressors and Resources and Their Association with Digital Stress in Germany—A Qualitative Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(12):1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121453

Chicago/Turabian StyleGebhardt, Julia Sofie, Volker Harth, David A. Groneberg, and Stefanie Mache. 2025. "Digitalization in Dentistry: Dentists’ Perceptions of Digital Stressors and Resources and Their Association with Digital Stress in Germany—A Qualitative Study" Healthcare 13, no. 12: 1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121453

APA StyleGebhardt, J. S., Harth, V., Groneberg, D. A., & Mache, S. (2025). Digitalization in Dentistry: Dentists’ Perceptions of Digital Stressors and Resources and Their Association with Digital Stress in Germany—A Qualitative Study. Healthcare, 13(12), 1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121453