Effects of Body Image and Self-Concept on the Management of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

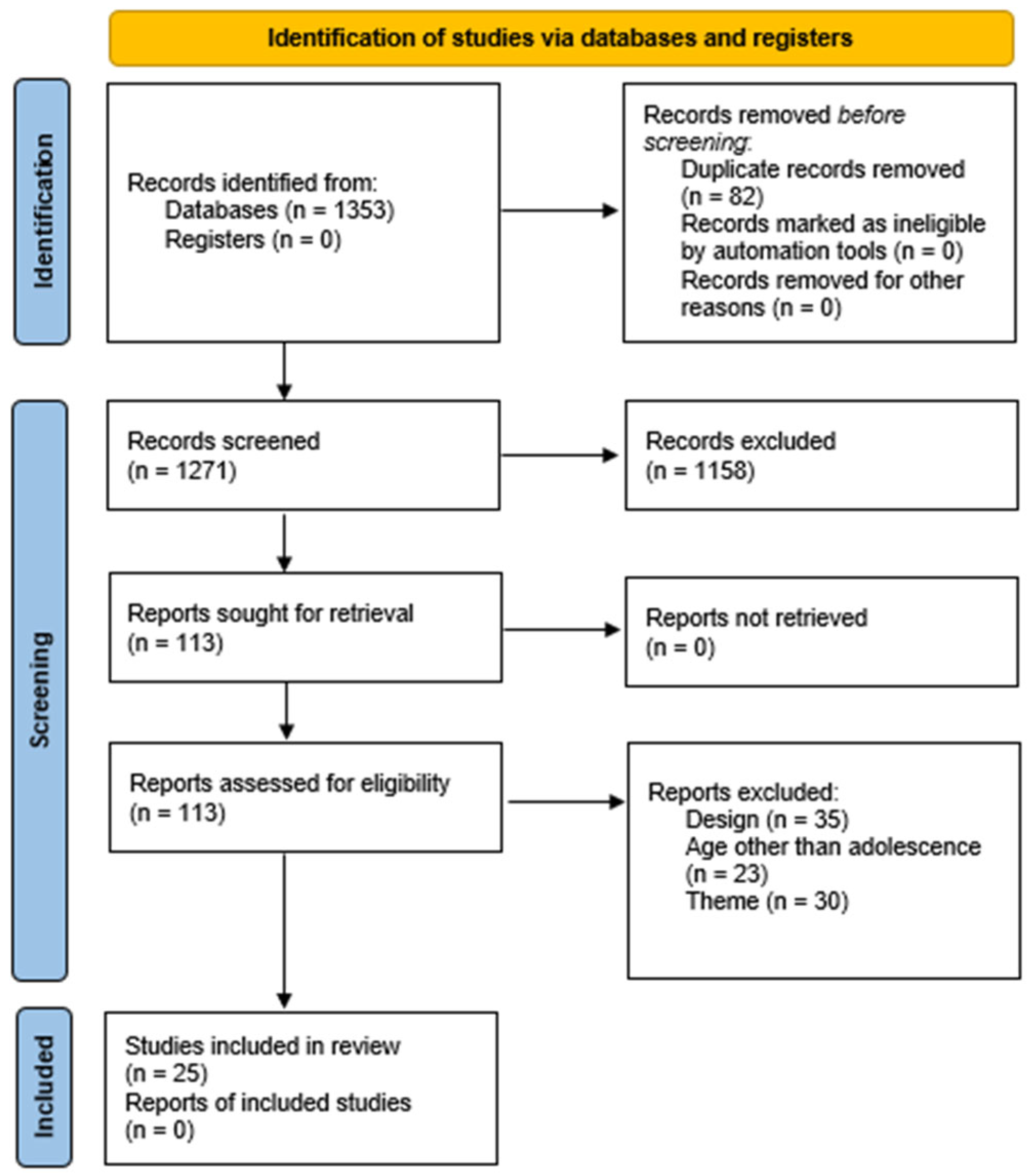

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Methods and General Characteristics of the Studies

3.2. Prevalence, Correlates, and Gender Differences in Body Image Concerns, Emotional Responses, and Self-Perception

3.3. Impact of Body Image Concerns and Self-Perception on Glycemic Control and T1DM Management

3.4. T1DM-Specific Stress, Identity, and Coping Mechanisms

3.5. Interventions Strategies and Gaps in the Psycho-Emotional Aspects of T1DM Management

4. Discussion

4.1. Identity Development and T1DM Management

4.2. Eating Behaviors and Glycemic Control

4.3. Gender Differences

4.4. Influence of Family and Social Environment

4.5. Limitations and Strengths

4.6. Future Perspectives

4.6.1. The Role of Technology in Psychological Support

4.6.2. Media and Social Media Influence

4.6.3. The Importance of Qualitative Approaches

4.6.4. Cross-Cultural Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| DEB | Disordered eating behavior |

| HbA1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| LGBT | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender |

| PEO | Person, Exposure, Outcome |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| T1DM | Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus |

References

- Garrido-Bueno, M.; Pabón-Carrasco, M.; Jiménez-Picón, N.; Romero-Castillo, R. Health Promotion in Glycemic Control and Emotional Well-Being of People with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas. 10th Edition. Available online: https://idf.org/about-diabetes/diabetes-facts-figures/ (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care 2021, 45, S17–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yapanis, M.; James, S.; Craig, M.E.; O’Neal, D.; Ekinci, E.I. Complications of Diabetes and Metrics of Glycemic Management Derived from Continuous Glucose Monitoring. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, e2221–e2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosak, L.; Stiglic, G. Cognitive and Emotional Perceptions of Illness in Patients Diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Healthcare 2024, 12, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prell, T.; Stegmann, S.; Schönenberg, A. Social Exclusion in People with Diabetes: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Results from the German Ageing Survey (DEAS). Sci. Rep. (Nat. Publ. Group) 2023, 13, 7113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Therapeutic Patient Education: Continuing Education Programmes for Health Care Providers in the Field of Prevention of Chronic Diseases: Report of a WHO Working Group; European Health 21 target 18, Developing Human resources for Health; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1998; ISBN 978-92-890-1298-0. [Google Scholar]

- Santa Cruz-Álvarez, P.; Ruiz-Trillo, C.A.; Pérez-Morales, A.; Cortés-Lerena, A.; Gamero-Dorado, C.; Garrido-Bueno, M. Educación Terapéutica Enfermera Sobre El Control Glucémico y Bienestar Emocional En Adolescentes Con Diabetes Mellitus de Tipo 1 Durante La Transición Hospitalaria. Endocrinol. Diabetes Y Nutr. 2025, 72, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inns, S.J.; Chen, A.; Myint, H.; Lilic, P.; Ovenden, C.; Su, H.Y.; Hall, R.M. Comparative Analysis of Body Image Dissatisfaction, Depression, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adults with Type 1 Diabetes: A Case-Control Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino, M.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F.; Rubio-Zarapuz, A.; Villanueva-Tobaldo, C.V.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Body Perceptions and Psychological Well-Being: A Review of the Impact of Social Media and Physical Measurements on Self-Esteem and Mental Health with a Focus on Body Image Satisfaction and Its Relationship with Cultural and Gender Factors. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.4 (Updated August 2023); Cochrane: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JBI. 2025 JBI Critical Appraisal Tools|JBI. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Tawfik, G.M.; Dila, K.A.S.; Mohamed, M.Y.F.; Tam, D.N.H.; Kien, N.D.; Ahmed, A.M.; Huy, N.T. A Step by Step Guide for Conducting a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Simulation Data. Trop. Med. Health 2019, 47, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufunaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetc, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al. Systematic Reviews of Etiology and Risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., Jordan, Z., Eds.; JBI: Kochi, India, 2024; ISBN 978-0-6488488-2-0. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, T.H.; Stone, J.C.; Sears, K.; Klugar, M.; Tufanaru, C.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. The Revised JBI Critical Appraisal Tool for the Assessment of Risk of Bias for Randomized Controlled Trials. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative Research Synthesis: Methodological Guidance for Systematic Reviewers Utilizing Meta-Aggregation. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackard, D.M.; Vik, N.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Schmitz, K.H.; Hannan, P.; Jacobs, D.R. Disordered Eating and Body Dissatisfaction in Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes and a Population-Based Comparison Sample: Comparative Prevalence and Clinical Implications. Pediatr. Diabetes 2008, 9, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brorsson, A.L.; Leksell, J.; Andersson Franko, M.; Lindholm Olinder, A. A Person-centered Education for Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes—A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatr. Diabetes 2019, 20, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryden, K.S.; Neil, A.; Mayou, R.A.; Peveler, R.C.; Fairburn, C.G.; Dunger, D.B. Eating Habits, Body Weight, and Insulin Misuse. A Longitudinal Study of Teenagers and Young Adults with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 1999, 22, 1956–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.-C.; Chou, Y.-Y.; Pan, Y.-W.; Ou, T.-Y.; Tsai, M.-C. Correlates of Disordered Eating and Insulin Restriction Behavior and Its Association with Psychological Health in Taiwanese Youths with Diabetes Mellitus. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commissariat, P.V.; Kenowitz, J.R.; Trast, J.; Heptulla, R.A.; Gonzalez, J.S. Developing a Personal and Social Identity with Type 1 Diabetes During Adolescence. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, L.; Haile, D.; Egata, G. Disordered Eating Behaviours and Body Shape Dissatisfaction among Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes: A Cross Sectional Study. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilander, M.M.A.; de Wit, M.; Rotteveel, J.; Aanstoot, H.J.; Bakker-van Waarde, W.M.; Houdijk, E.C.A.M.; Nuboer, R.; Winterdijk, P.; Snoek, F.J. Disturbed Eating Behaviors in Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. How to Screen for Yellow Flags in Clinical Practice? Pediatr. Diabetes 2017, 18, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elissa, K.; Bratt, E.-L.; Axelsson, A.B.; Khatib, S.; Sparud-Lundin, C. Self-Perceived Health Status and Sense of Coherence in Children with Type 1 Diabetes in the West Bank, Palestine. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2020, 31, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawlik, N.R.; Elias, A.J.; Bond, M.J. Appearance Investment, Quality of Life, and Metabolic Control Among Women with Type 1 Diabetes. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2016, 23, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, A.C.; Seiffge-Krenke, I.; Laursen, B. Body Image Mediates Negative Family Climate and Deteriorating Glycemic Control for Single Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. Fam. Syst. Health 2015, 33, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.M.; Quinn, L.; Kim, N.; Martyn-Nemeth, P. Health-Related Stigma in Young Adults with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2018, 56, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyckx, K.; PHD; Seiffge-Krenke, I. PHD Continuity and Change in Glycemic Control Trajectories from Adolescence to Emerging Adulthood: Relationships with Family Climate and Self-Concept in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowitz, J.T.; Alleyn, C.A.; Phillips, R.; Muir, A.; Young-Hyman, D.; Laffel, L.M.B. Disordered Eating Behaviors in Youth with Type 1 Diabetes: Prospective Pilot Assessment Following Initiation of Insulin Pump Therapy. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2013, 15, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, L.; Johnson, S.; Prine, J.; Banks, R.; Desrosiers, P.; Silverstein, J. Disordered Eating, Body Mass, and Glycemic Control in Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmsted, M.P.; Colton, P.A.; Daneman, D.; Rydall, A.C.; Rodin, G.M. Prediction of the Onset of Disturbed Eating Behavior in Adolescent Girls with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 1978–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peducci, E.; Mastrorilli, C.; Falcone, S.; Santoro, A.; Fanelli, U.; Iovane, B.; Incerti, T.; Scarabello, C.; Fainardi, V.; Caffarelli, C.; et al. Disturbed Eating Behavior in Pre-Teen and Teenage Girls and Boys with Type 1 Diabetes. Acta Bio-Medica Atenei Parm. 2019, 89, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassart, J.; Oris, L.; Prikken, S.; Goethals, E.R.; Raymaekers, K.; Weets, I.; Moons, P.; Luyckx, K. Illness Identity and Adjusting to Type I Diabetes: A Four-Wave Longitudinal Study. Health Psychol. 2021, 40, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, C.; Lin, A.; Smith, G.; Yeung, A.; Strauss, P.; Nicholas, J.; Davis, E.; Jones, T.; Gibson, L.; Richters, J.; et al. The Impact of Externally Worn Diabetes Technology on Sexual Behavior and Activity, Body Image, and Anxiety in Type 1 Diabetes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2020, 14, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salah, N.; Hashem, M.; Abdeen, M. Body Image Perception among Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus; Relation to Glycemic Variability, Depression and Disordered Eating Behaviour. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2024, 97, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sien, P.L.M.; Jamaludin, N.I.A.; Samrin, S.N.A.; Shanita, N.S.; Ismail, R.; Zaini, A.A.; Sameeha, M.J. Causative Factors of Eating Problems among Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: A Qualitative Study. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncone, A.; Cascella, C.; Chianese, A.; Galiero, I.; Zanfardino, A.; Confetto, S.; Perrone, L.; Iafusco, D. Changes in Body Image and Onset of Disordered Eating Behaviors in Youth with Type 1 Diabetes over a Five-Year Longitudinal Follow-Up. J. Psychosom. Res. 2018, 109, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troncone, A.; Cascella, C.; Chianese, A.; Zanfardino, A.; Piscopo, A.; Borriello, A.; Casaburo, F.; del Giudice, E.M.; Iafusco, D. Body Image Problems and Disordered Eating Behaviors in Italian Adolescents with and Without Type 1 Diabetes: An Examination With a Gender-Specific Body Image Measure. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 556520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, J.; Nansel, T.R.; Haynie, D.L.; Mehta, S.N.; Laffel, L.M.B. Disordered Eating Behaviors Are Associated with Poorer Diet Quality in Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 1810–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderhaegen, J.; Raymaekers, K.; Prikken, S.; Claes, L.; Van Laere, E.; Campens, S.; Moons, P.; Luyckx, K. Personal and Illness Identity in Youth with Type 1 Diabetes: Developmental Trajectories and Associations. Health Psychol. 2024, 43, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.E.; Smith, E.L.; Coker, S.E.; Hobbis, I.C.A.; Acerini, C.L. Testing an Integrated Model of Eating Disorders in Paediatric Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Pediatr. Diabetes 2015, 16, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on the Neurobiological and Socio-behavioral Science of Adolescent Development and Its Applications; Backes, E.P.; Bonnie, R.J. Adolescent Development. In The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bombaci, B.; Torre, A.; Longo, A.; Pecoraro, M.; Papa, M.; Sorrenti, L.; La Rocca, M.; Lombardo, F.; Salzano, G. Psychological and Clinical Challenges in the Management of Type 1 Diabetes during Adolescence: A Narrative Review. Children 2024, 11, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanning, M.S.; Tanenbaum, M.L.; Wong, J.J.; Hood, K.K. Barriers to Continuous Glucose Monitoring in People with Type 1 Diabetes: Clinician Perspectives. Diabetes Spectr. 2020, 33, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beam, A.B.; Wiebe, D.J.; Berg, C.A. Insulin Restriction, Emotion Dysregulation, and Depressive Symptoms in Late Adolescents with Diabetes. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2021, 46, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, I.; Yuasa, M. Childhood Obesity in South-Asian Countries: A Systematic Review (Causes and Prevention). Juntendo Med. J. 2018, 64, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araia, E.; King, R.M.; Pouwer, F.; Speight, J.; Hendrieckx, C. Psychological Correlates of Disordered Eating in Youth with Type 1 Diabetes: Results from Diabetes MILES Youth-Australia. Pediatr. Diabetes 2020, 21, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Morros, A.; Berenguera, A.; Millaruelo, L.; Buil-Cosiales, P.; Gomez Garcia, C.; Cos, X.; Ávila Lachica, L.; Artola, S.; Millaruelo, J.M.; Mauricio, D.; et al. Impact of Gender on Patient Experiences of Self-Management in Type 2 Diabetes: A Qualitative Study. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2024, 18, 1885–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN DESA. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ciarambino, T.; Crispino, P.; Leto, G.; Mastrolorenzo, E.; Para, O.; Giordano, M. Influence of Gender in Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complication. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Bueno, M.; Dorcé, N.; Zaldívar Fernández, M.C. Narrativas de Género Sobre Diabetes Mellitus En Foros Online: Un Proyecto de Investigación Etnográfica Digital. In Innovación en Salud: Nuevas Estrategias Para la Enseñanza y la Investigación; del Mar Simón Márquez, M., Barragán Martín, A.B., Molina Moreno, P., Gázquez Linares, J.J., Martínez Casanova, E., Eds.; Dialnet: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2025; ISBN 979-13-990275-3-2. [Google Scholar]

- Azar, S.; Maroun Abou Jaoude, N.; Kędzia, A.; Niechciał, E. Barriers to Type 1 Diabetes Adherence in Adolescents. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, A.; Tanveer, F.; Sharif, F. Sadia Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Symptoms and Its Associated Risk Factors in Touchscreen Tablet Computer Users. Rawal Med. J. 2020, 45, 382–384. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchison, D. AI-Readiness in the Eating Disorders Field. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alowais, S.A.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Alsuhebany, N.; Alqahtani, T.; Alshaya, A.I.; Almohareb, S.N.; Aldairem, A.; Alrashed, M.; Bin Saleh, K.; Badreldin, H.A.; et al. Revolutionizing Healthcare: The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Clinical Practice. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiotsa, B.; Naccache, B.; Duval, M.; Rocher, B.; Grall-Bronnec, M. Social Media Use and Body Image Disorders: Association between Frequency of Comparing One’s Own Physical Appearance to That of People Being Followed on Social Media and Body Dissatisfaction and Drive for Thinness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahramani, A.; de Courten, M.; Prokofieva, M. The Potential of Social Media in Health Promotion beyond Creating Awareness: An Integrative Review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtz, B.E.; Kanthawala, S. #T1DLooksLikeMe: Exploring Self-Disclosure, Social Support, and Type 1 Diabetes on Instagram. Front. Commun. 2020, 5, 510278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.E.; Cooper, H.C.; Milton, B. The Lived Experiences of Young People (13–16 Years) with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and Their Parents—A Qualitative Phenomenological Study. Diabet. Med. 2013, 30, e17–e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povlsen, L.; Olsen, B.; Ladelund, S. Diabetes in Children and Adolescents from Ethnic Minorities: Barriers to Education, Treatment and Good Metabolic Control. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 50, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juarascio, A.S.; Forman, E.M.; Herbert, J.D. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Versus Cognitive Therapy for the Treatment of Comorbid Eating Pathology. Behav. Modif. 2010, 34, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, K.K.; Hilliard, M.; Piatt, G.; Ievers-Landis, C.E. Effective Strategies for Encouraging Behavior Change in People with Diabetes. Diabetes Manag. 2015, 5, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempler, N.F.; Laursen, D.H.; Glümer, C. Culturally Sensitive Diabetes Education Supporting Ethnic Minorities with Type 2 Diabetes. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, ckz186.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Strategy | Search Date | Outcomes | Selected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (“adolescen*”[All Fields] OR “teen*”[All Fields] OR “young adult*”[All Fields]) AND (“type 1 diabet*”[All Fields] OR “diabetes mellitus type 1”[All Fields] OR “T1DM”[All Fields] OR “T1D”[All Fields] OR “type 1 DM”[All Fields]) AND (“body imag*”[All Fields] OR “self imag*”[All Fields] OR “self perce*”[All Fields]) AND (“self manag*”[All Fields] OR “self car*”[All Fields] OR “patient educat*”[All Fields] OR “diabetes manag*”[All Fields] OR “glycemic control”[All Fields] OR “treatment adheren*”[All Fields] OR “patient compli*”[All Fields]) | 01/03/25 | 57 | 5 |

| WOS | (adolescen* OR teen* OR “young adult*”) AND (“type 1 diabet*” OR “diabetes mellitus type 1” OR “T1DM” OR “T1D” OR “type 1 DM”) AND (“body imag*” OR “self-imag*” OR “self-perce*”) AND (“self-manag*” OR “self-car*” OR “patient educat*” OR “diabetes manag*” OR “glycemic control” OR “treatment adheren*” OR “patient compli*”) (Topic) | 07/03/25 | 82 | 1 |

| CINAHL | (adolescen* OR teen* OR “young adult*”) AND (“type 1 diabet*” OR “diabetes mellitus type 1” OR “T1DM” OR “T1D” OR “type 1 DM”) AND (“body imag*” OR “self-imag*” OR “self-perce*”) AND (“self-manag*” OR “self-car*” OR “patient educat*” OR “diabetes manag*” OR “glycemic control” OR “treatment adheren*” OR “patient compli*”) | 13/03/25 | 35 | 3 |

| Scopus | 20/03/25 | 73 | 3 | |

| Embase | (adolescen* OR teen* OR ‘young adult*’) AND (‘type 1 diabet*’ OR ‘diabetes mellitus type 1′/exp OR ‘diabetes mellitus type 1′ OR ‘t1dm’/exp OR ‘t1dm’ OR ‘t1d’ OR ‘type 1 dm’) AND (‘body imag*’ OR ‘self-imag*’ OR ‘self-perce*’) AND (‘self-manag*’ OR ‘self-car*’ OR ‘patient educat*’ OR ‘diabetes manag*’ OR ‘glycemic control’/exp OR ‘glycemic control’ OR ‘treatment adheren*’ OR ‘patient compli*’) | 25/03/25 | 82 | 6 |

| APA PsycInfo | “(adolescen* OR teen* OR (“young adult” OR “young adulthood” OR “young adults”)) AND (“type 1 diabet*” OR “diabetes mellitus type 1” OR “T1DM” OR “T1D” OR “type 1 DM”) AND ((“body image” OR “body images” OR “body imaging”) OR “self-imag*” OR “self-perce*”) AND (“self-manag*” OR “self-car*” OR (“patient education”) OR (“diabetes management”) OR “glycemic control” OR (“treatment adherence”) OR (“patient compliance”))” | 01/04/25 | 972 | 4 |

| APA PsycArticles | 02/04/25 | 52 | 3 | |

| Total | 1353 | 25 |

| Author, Year, Reference and Region | Methodology: 1. Design 2. Intervention 3. Variables of interest 4. Sample 5. JBI Score | Aim | Main Results and Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ackard et al. [19] 2008 United States | Cross-sectional study. Without intervention. Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) group: 143 adolescents (73 men and 70 women) who participated in the AHEAD study. The average age was 15.3 years. Comparison group (general population): 4746 youth (2377 men, 2357 women, and 12 of unspecified sex) who participated in Project EAT. The mean age was 14.9 years. JBI: 5/8. | To compare the prevalence of disordered eating and body dissatisfaction among adolescents with T1DM and a sample of young people from the general population. | Adolescents with T1DM did not have a higher risk of unhealthy weight-control behaviors or weight dissatisfaction compared to other adolescents. In fact, they reported less weight dissatisfaction and were less likely to engage in some unhealthy weight-control behaviors. Furthermore, they consumed meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) more frequently than their peers without diabetes. However, despite medical supervision, the study identified a concerning prevalence of insulin manipulation as a means of weight control among youth with T1DM. Specifically, a significant percentage of girls (10.3%) and a small percentage of boys (1.4%) with diabetes reported skipping insulin doses or taking less than prescribed to lose weight or prevent weight gain. This finding is of great concern given the serious medical complications associated with inadequate glycemic control. Further analysis revealed that adolescents with diabetes who manipulated insulin were more likely to report body dissatisfaction than those with diabetes who did not. Approximately 45.5% of youth with diabetes who manipulated insulin were very dissatisfied or dissatisfied with their weight, compared to 10.9% of those who did not. No significant differences in Body Mass Index (BMI) were found between these two groups. |

| Brorsson et al. [20] 2019 Sweden | Randomized clinical trial. The intervention group attended seven group sessions over a five-month period, using the GSD-Y model. The control group received standard care. Variables: Glycated hemoglobin (Hb A1c) at 6 and 12 months, self-perceived health, health-related quality of life, family conflicts, self-efficacy, and use of continuous glucose monitoring. The sample consisted of n = 41 women and n = 28 men. Their ages ranged from 12 to 17.99 years. JBI: 9/13. | To evaluate whether the person-centered education and communication model, called Guided Self-Determination-Young (GSD-Y), improves glycemic control, self-rated health, health-related quality of life, reduces diabetes-related family conflicts, and improves self-efficacy in adolescents who initiate continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) therapy with their parents. | When adjusted for sex and family conflict, there were no differences in Hb A1c between the intervention and control groups at enrollment; 8.4% (SD 0.9%) vs. 8.8% (SD 1.2%) (68 [SD 10.2] vs. 73 [SD 12.7] mmol/mol, p = 0.06); or at 6 months: 7.6% (SD 0.9%) vs. 8.0% (SD 1.0%) (60 [SD 9.8] vs. 64 [SD 10.4] mmol/mol, p = 0.19). At 12 months, a difference was detected between the groups: 7.8% (SD 1.1%) vs. 8.6% (SD 1.1%) (62 (SD 11.4) vs. 70 (SD 12.1) mmol/mol, p = 0.009). When analyses were performed for boys and girls separately and adjusted for family conflict, a difference was detected for boys after 12 months: 7.4% (SD 0.9%) vs. 8.3% (SD 1.1%) (57.0 (SD 10.1) vs. 67.3 (SD 11.5) mmol/mol, p = 0.019). In boys, an intervention effect was identified after 6 months: −1.0% (SE 0.3%) (−11.1 [SE 3.7] mmol/mol, p = 0.004) and 12 months: −1.0% (SE 0.3%) (−11.2 [SE 3.5] mmol/mol, p = 0.002). In girls, a difference was only identified in the control group after 6 months: −0.8% (SE 0.3%) (−8.2 [SE 3.7] mmol/mol, p = 0.029). The level of family conflicts was 25 (25, 27) at the beginning (n = 66), 25 (24, 28) at 6 months (n = 48) and 24 (23, 27) at 12 months (n = 39). At baseline, the intervention group perceived more family conflicts related to diabetes (intervention 25 vs. control 22, p = 0.027), but there were no differences were observed at six months (intervention 24 vs. control 23, p = 0.258) or twelve months (intervention 22 vs. control 24, p = 0.417). At baseline, the control group had a higher total score on the Swe-DES “Readiness to Change” domain and a lower perceived physical burden of diabetes. There were no differences in health, health-related quality of life, or diabetes burden between the groups at 6 or 12 months. There were no significant differences in Hb A1c values between adolescents who used CGM and those who did not use it at any time during the study. |

| Bryden et al. [21] 1999 UK | Longitudinal observational study. Quantitative approach with analysis of data collected over 8 years. Without intervention Eating habits, weight, glycemic control, and insulin use were monitored in adolescents with T1DM. Anthropometric variables: Weight, height, body mass index (BMI). Psychological variables: Concern about body shape and weight, dietary restriction, and presence of eating disorders (measured with the Eating Disorder Examination). Insulin Use: Record of intentional omission or reduction in insulin for weight control. Glycemic control: Glycosylated hemoglobin (Hb A1c) levels. Diabetic complications: Urine albumin/creatinine ratio and presence of microvascular complications (retinopathy, nephropathy, hypertension). Initial population: 76 adolescents (43 men and 33 women) with T1DM, aged 11–18 years, assessed in 1989–1990 and diagnosed with diabetes at least one year before the start of the study. Follow-up: 65 of the original 76 participants (86%) were reassessed between 1997 and 1998, when they were aged 20–28 years (one of the non-interviewees died of diabetic ketoacidosis, another died of severe mental disability due to a severe hypoglycemic episode). JBI: 6/11. | To examine the relationship between dietary habits, insulin misuse, changes in body weight, and their impact on glycemic control and diabetic complications in adolescents with T1DM over eight years. To explore the relationship between eating disorders/insulin misuse and glycemic control, as well as the presence of diabetic complications. | Height, weight, and BMI; formula: [(observed population mean)/population SD], appropriate for the subject’s sex and age. Initial and follow-up assessment of eating disorder features was performed using the Eating Disorders Examination. The interview was adapted to distinguish between behaviors necessary for diabetes management, such as avoiding sugary foods for glycemic control, and those attributable to an eating disorder, such as extreme dietary restriction for figure and weight control. At each assessment, subjects were asked whether they had ever reduced or omitted insulin use to lose weight. At the follow-up assessment, past and present misuse and its probable duration were determined. Weight gain: Both men and women increased their weight and BMI from adolescence to adulthood, with women being overweight at both assessments. Weight concern: Increased significantly in both sexes, reflected in higher levels of dietary restriction. Women showed significantly greater concern about weight and shape at follow-up than during adolescence. Of the women who expressed greater weight concern at follow-up, 72% had a BMI of one standard deviation greater than at baseline. Men showed a similar pattern of greater concern at follow-up, although at much lower levels than women at both assessments. Weight change in men, but not in women, correlated with change in level of dietary restraint (rs = 0.42; p = 0.008). Eating disorders: No cases of anorexia or bulimia nervosa were identified, but mild forms of eating disorders were observed, especially in women. Six subjects (one man and five women) from either the initial assessment (n = 3) or the follow-up interview (n = 3) met criteria for eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS), either with markedly abnormal behavior (n = 3), such as recurrent self-induced vomiting or laxative use, or with abnormal importance given to shape and weight (n = 3). One woman was classified as having EDNOS at both assessments. She was diagnosed with bulimia nervosa between the completion of the initial and follow-up interviews, and has been receiving treatment for several years. Insulin misuse: 30% of women admitted to intentionally reducing or omitting insulin to control their weight. The duration of misuse varied considerably, with a minimum of 3 months and an average of 2 years. Forty-five percent of women with microvascular complications had engaged in this practice. Four women who had abused insulin were among the six subjects classified as having a clinical eating disorder (CED). No women admitted to insulin abuse at the follow-up evaluation. No men admitted to deliberate insulin abuse in any of the evaluations. Glycemic control: No relationship was observed between subjects with EDNOS and glycemic control, nor was there any difference between the glycemic control of subjects with EDNOS with abnormal behavior (vomiting, laxative use) and those with abnormal psychiatric behavior. The mean Hb A1c of the ten women who admitted to intentional insulin misuse was worse than that of the remaining women, both at baseline (10.3 ± 1.1 vs. 9.5 ± 2.0) and at follow-up (9.7 ± 1.8 vs. 9.2 ± 1.9), although none of the differences were statistically significant. Risk of complications: Insulin omission was associated with poor glycemic control and could contribute to the development of diabetic complications. Of the women who developed microvascular complications, five (46%) deliberately misused insulin (one was diagnosed with EDNOS at baseline and one with EDNOS during follow-up). Two women had laser-treated proliferative retinopathy, two had nephropathy, and one had both laser-treated proliferative retinopathy and nephropathy. No significant associations were observed between baseline eating disorders or insulin misuse and the development of diabetic complications. An overall mean Hb A1c over the 8 year period between baseline and follow-up shows significantly worse long-term glycemic control in these subjects. |

| Chou et al. [22] 2023 Taiwan | Quantitative. Without intervention. n = 110 patients with T1DM and n = 32 with Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). All were receiving insulin treatment at a tertiary care center. Age, mean (SD): T1DM 17.70 years (5.05); T2DM 16.19 years (4.14) JBI: 7/8. | To investigate the clinical and behavioral interrelationship between eating disorders and insulin restriction and their association with psychological health. | Patients with T1DM tended to be less concerned about body image and used medication less as a method of weight control. Regarding the univariate regression analysis, it was observed that the CR of the TFEQ-R21 scale was (OR = 2.37, [95% CI: 1.04–5.40]), body image (OR = 2.07, [95% CI: 1.25–3.44]), diet (OR = 6.48, [95% CI: 2.50–16.77]), and excessive exercise (OR = 8.42, [95% CI: 1.51–46.85]), which were associated with an mSCOFF score of 2 or higher. In contrast, only Hb A1c-SD (OR = 2.18, [95% CI 1.07–4.42]), body image (OR = 1.83, [95% CI 1.05–3.20]), and diet (OR = 4.74, [95% CI 1.70–13.23]) were associated with an mSCOFF score of 2 or higher. Hierarchical regression analysis showed a lower standard deviation of Hb A1c (odds ratio = 2.1 8, [95% CI: 1.07–4.42]), body image (1.83, [1.05–3.20]), and diet (4.74, [1.70–13.23]) associated with disordered eating behavior (DEB) and clinical and behavioral correlations between eating disorders and insulin restriction (ED/IR). Furthermore, ED/IR behavior was associated with anxiety (1.17 [1.08–1.27]) and depression (1.12 [1.03–1.22]). Across the different forms, it was observed that mSCOFF scores were consistently associated with depression and anxiety according to the HADS questionnaire, even after controlling for clinical and behavioral parameters. In the fully adjusted model, an mSCOFF score of 2 or higher was associated with a 17% increased OR for anxiety and a 12% increased OR for depression according to the HADS questionnaire. |

| Commissariat et al. [23] 2016 USA | Qualitative. Without intervention. Hb A1c, a total of 5 questions about living with diabetes and self-image with diabetes n = 40. Forty-seven percent of the participants were women (n = 19). Participants ranged in age from 13 to 30 years. The mean age of the sample was 16.15 ± 1.89 years. JBI: 10/10. | Exploring the incorporation of T1DM into self-identity among adolescents. | One of the main themes is diabetes as a burden on daily life. Within this theme, adolescents’ express feelings of frustration and exhaustion due to the constant need to monitor their health. “It’s like going through an epic journey where you know you’re not going to reach a finish line, but everybody tells you it’s about trying. It’s difficult to look yourself in the face in the morning if you know you haven’t done what you need to do, and so I feel like diabetes is associated with a big guilt trip, and it’s life-long, and it sucks, hard” (19-year-old female). In some cases, adolescents choose denial or rejection of treatment as a way to cope with the disease. “I think I almost sabotage myself sometimes because I want to get back at it or rebel. I think it’s interesting what the mind does sometimes. I sabotage myself. Like too eating much or not bolusing the way I should. I’m only harming myself, not anyone else. It’s just a really bad habit that I formed” (17-year-old female). Concerns about body image are also present, as some adolescents have been the subject of negative comments or ridicule due to the medical devices they use. “In public, I didn’t like checking my blood sugar and taking needles because someone would always ask, ‘What is that, what’re you doing?’ I had an incident before where I was actually made fun of, for having a really old pump. Then I took my pump off and didn’t wear it for almost 2 years because I was insecure about it” (17-year-old female). However, other adolescents describe a process of acceptance and adaptation over time. “Now I’m at a place where it’s just I’ve accepted it. It’s something I know I’m going to live with for the rest of my life, I know there’s nothing I can do except learn to take care of it and be healthy about it… you just have to learn the steps necessary for you to be a healthy member of society and for you to learn that this is what you have to deal with” (18-year-old female). |

| Daniel et al. [24] 2023 Ethiopia | Cross-sectional study. Without intervention. The study focused on the prevalence of disordered eating behaviors and how they related to body shape dissatisfaction in a group of adolescents with T1DM receiving medical care in hospitals in Addis Ababa. The study sample consisted of a total of 395 adolescents with diabetes. Regarding age, participants ranged in age from 10 to 19 years. The median (±IQR) age of participants was 15 (±11 to 19) years, and the majority (approximately 61%) were in their early teens (11–15 years). 52.2% were women and 47.8% were men. JBI: 7/8. | To assess the magnitude of DEBs and their relationship with body shape dissatisfaction among adolescents with diabetes in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. | The results revealed a high prevalence of BDDs in this population, reaching 43.3% in the past 30 days. Furthermore, 20.3% of adolescents reported dissatisfaction with their body shape. One of the most relevant findings was the significant association between body dissatisfaction and the presence of BDDs. Adolescents dissatisfied with their body were 2.2 times more likely to develop DEBs. In addition to body image, other factors significantly associated with BDDs included having a family history of diabetes mellitus, being in late adolescence (16–19 years), experiencing diabetic complications, and being overweight. Regarding the types of eating behaviors observed, a higher prevalence of non-purging behaviors, such as skipping meals and avoiding glycemic control, was identified, rather than more aggressive practices such as self-induced vomiting. Furthermore, scores on the DEPS-R scale were significantly higher among adolescents with body dissatisfaction, overweight, and those from higher-income families. However, no significant differences were found in these scores between males and females. The study’s findings highlight that DEBs constitute a significant health problem among adolescents with T1DM in this context. Furthermore, factors such as negative body image, overweight, family background, and health complications associated with diabetes significantly contribute to the development of these behaviors. |

| Eilander et al. [25] 2017 Netherlands | Quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional. Without intervention. Age, age at onset, duration of diabetes, family structure, type of treatment, Hb A1c n = 103. The mean age was 13.5 years (SD = 1.49); n = 53, 51.5% of participants were girls. JBI: 6/8. | To explore the prevalence of DEBs and associated ‘yellow flags’. | In total, 80.4% (n = 83) of participants used an insulin pump as part of their treatment. The mean Hb A1c was 8.0% (SD = 0.64) [range: 5.1–15.8%]. The mean age-adjusted BMI (BMIz) was 0.64 (SD = 1.0). The mean age at diabetes onset was 7.0 years (SD = 3.9), and the duration of diabetes was 6.5 years (SD = 3.8). In total, 46.5% of adolescents with T1DM reported concerns about their body image and weight. Eight percent of participants exceeded the clinical threshold for DEBs. Adolescents with DEBs had higher Hb A1c levels, with a statistically significant difference (p = 0.004). These adolescents were also found to have lower confidence in their self-care and diabetes management (p = 0.015), which is associated with a reduction in their quality of life (p = 0.007). Adolescents with DEBs showed significant impairment in diabetes management (p < 0.001). Body dissatisfaction was related to the presence of DEBs (p < 0.001), while BMI was not. Dieting frequency was found to be a significant risk factor for the development of DEBs (p = 0.001). |

| Elissa et al. [26] 2020 Palestine | Quantitative, cross-sectional study. Without intervention. n = 300 healthy children aged 8–18 from six primary, secondary and high schools in the north, south and central West Bank. JBI: 7/8. | To measure perceived health status in adolescents and sense of coherence (SOC) in children with T1DM and to examine possible correlations between sociodemographic and medical characteristics. | Regarding self-perceived health status, men showed a higher level compared to women, M = 84.0 (SD = 11.44) versus 75.21 (SD = 17.86), p = 0.008, on the generic scale. The study found a positive correlation between self-perceived health status and SOC, directly proportional; higher self-perceived health status was associated with higher SOC (p < 0.001). Furthermore, a negative correlation was found between perceived health status and Hb A1c (p = 0.003). The higher the perceived health, the lower the Hb A1c, i.e., the better the glycemic control. The relationship between SOC and Hb A1c was found to be negative (p = 0.012), where a higher SOC was associated with a lower Hb A1c. |

| Gawlik et al. [27] 2015 Australia | Quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional. Without intervention. Age, diabetes duration, quality of life, salience, Hb A1c, body image, adjustment to diabetes n = 177. The mean age of participants was 36.32 years (SD = 11.33, n = 176), with a range of 18 to 68 years. JBI: 5/8. | To study and evaluate the associations between the appearance investment component of body image, age, quality of life, and self-reported metabolic control. | The mean duration of diabetes was 18.39 years (SD = 11.15, n = 176), with a range from 1 to 48 years. The mean self-reported Hb A1c was 7.84% (SD = 1.63, n = 169), with a range from 4.5 to 14.7%. The results showed that self-evaluative salience (the degree to which appearance influences self-worth) was higher in younger participants (p < 0.001), those with a lower quality of life (p < 0.001), and those with better metabolic control (p < 0.001). On the other hand, motivational salience (the degree of attention and effort devoted to appearance) was not significantly associated with any of the study variables. Participants who reported restricting insulin to control their weight showed higher self-evaluative salience (p < 0.001), lower quality of life (p < 0.001), and worse levels of metabolic control (higher Hb A1c, p < 0.05). The prevalence of insulin restriction in the sample was 21%. The study also confirmed that hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia were associated with a worse quality of life (p < 0.01). |

| Hartl et al. [28] 2015 Germany | Quantitative, descriptive, longitudinal. Without intervention. Age, age of diagnosis, family type, perceived family climate, body image, relationship status n = 109. The mean age of participants was 15.84 years (SD = 1.44), with a range of 13 to 19 years. The sample consisted of n = 51 (46.8%) girls and n = 58 (53.2%) boys. JBI: 9/11. | To assess whether body image mediates longitudinal links between family climate and changes in glycemic control in adolescents. | The majority of participants came from families with two biological parents (n = 94, 86%). Among adolescents who were not in a romantic relationship, body image mediated the relationship between family climate and changes in glycemic control over time. A worse family climate at age 16 was associated with worse body image perception at the same year (β = 0.56, p < 0.001), which in turn predicted deterioration in glycemic control between ages 16 and 17 (β = −0.43, p < 0.05). The direct relationship between family climate and glycemic control was no longer significant when body image was included in the analysis (indirect effect: β = −0.24, SE = 0.09, p = 0.007). In adolescents who were in a romantic relationship, no significant associations were found between family climate and changes in glycemic control (β = −0.02, p > 0.05), nor was there a mediating effect of body image (indirect effect: β = 0.00, SE = 0.004, p > 0.05). Furthermore, the correlation between body image and glycemic control at age 17 was negative and significant only in single adolescents (r = −0.54, p < 0.001), whereas it was not observed in those with a partner (r = −0.02, p > 0.05). |

| Jeong et al. [29] 2018 South Korea | Descriptive qualitative study using focus groups. Two focus group sessions were conducted with a total of 14 participants. A semi-structured conversation format with an interview guide and verbal probing techniques were used to obtain participants’ responses. n = 14 participants. Regarding gender, there were nine women (64.3%) and five men (35.7%). The participants’ ages ranged from 20 to 34 years (mean = 26.5 years; SD = 4.5 years). JBI: 10/10. | To explore health-related stigma among young adults with T1DM using descriptive qualitative methods in focus groups. | The results revealed five main themes. First, participants expressed a strong desire to be recognized as people and not just as individuals with a disease, feeling frustration when their identity was reduced to their medical condition. They also expressed a longing for normality and to be equal to their peers without T1DM, which sometimes led them to avoid self-monitoring their glucose and insulin. Embarrassment about managing diabetes in public caused stress and promoted concealment of their self-care practices. Another important finding was anger and distress stemming from stereotypes and lack of knowledge about T1DM, along with distrust from family members and healthcare professionals regarding their ability to manage the disease independently. In terms of body image and self-image, stigma negatively affected participants’ self-perception. The feeling of being seen only because of their diagnosis and low self-esteem associated with social devaluation contributed to a negative identity. The desire to “be like everyone else” reflected how diabetes generated feelings of difference compared to their peers. |

| Luyckx et al. [30] 2009 Germany | Eight-phase longitudinal cohort study. Family climate (at times 1–4) and self-concept (at times 1–4 and 6) were assessed. Times 1–4 covered adolescence, with mean ages of 14 to 17 years, respectively. Times 5–8 covered emerging adulthood, with mean ages of 21 to 25 years, respectively. Glycemic control, general family climate, and self-concept. n = 72 people with T1DM. At time 1, the start of the study, the mean age was 13.72 years (SD = 1.46). The age range covered adolescence (mean ages 14–17 years) and emerging adulthood (mean ages 21–25 years). 37 women and 35 men. JBI: 7/11. | To determine developmental patterns of glycemic control in young people with T1DM throughout adolescence and emerging adulthood, and to assess relationships with overall family climate and self-concept. | Throughout adolescence and emerging adulthood, the study identified three distinct trajectories of glycemic control in people with T1DM: optimal, moderate, and impaired. The data showed that those with optimal glycemic control tended to maintain a higher positive self-concept, especially at key points in the study. Conversely, those with impaired control scored lowest on this psychological dimension. From late adolescence onward, these trajectories began to differentiate more clearly, intensifying during emerging adulthood. Both family climate and self-concept in middle and late adolescence were observed to act as psychosocial markers associated with these trajectories. Self-concept was assessed using the Offer Self-Image Questionnaire, which includes dimensions of the psychological self—such as impulse control, emotional tone, and body image—and the coping self. Although body image was not analyzed independently, it was considered an essential component of overall self-concept. These findings reinforce previous research indicating a significant relationship between self-concept and the evolution of glycemic control. They also highlight the importance of fostering a positive self-concept in adolescents with T1DM, as this could translate into sustained benefits for disease management. In particular, it has been observed that adolescents may experience lower self-esteem and greater distress related to their condition, factors possibly linked to self-image, although this dimension has not been explored in detail. Ultimately, this research highlights the role of self-concept as a relevant psychosocial factor in the treatment and progression of T1DM, and suggests that strengthening this dimension during adolescence could contribute to better long-term glycemic control. |

| Markowitz et al. [31] 2013 USA | Quantitative, control study. Without intervention. Sample: At baseline there were 43 young people (45% women) with T1DM, although the analyses include only the 37 participants, aged 10–17 years, who completed the Diabetes Specific Eating Problems Score (DSPS-R) at all three time points. JBI: 6/11. | To investigate the DSPS-R, a validated measure of risk for both diabetes-specific and general eating disorders. | Those enrolled in the study had a mean Hb A1c level of 8.3–1.3% (68%–14.5 mmol/mol) at baseline. DEPS-R scores decreased over time (p = 0.01). The overall rate of high-risk eating disorders was low. Overweight/obese youth experienced more DEBs than normal-weight participants. DEPS-R scores correlated with body mass index z score at all three time points and with Hb A1c at 1 and 6 months. Hb A1c did not change significantly and was higher in overweight/obese participants than in normal-weight participants (8.7% [72 mmol/mol] vs. 7.8% [62 mmol/mol]; p = 0.005). One-third of participants decreased A1c by 0.5% (5 mmol/mol), one-third increased it by ±0.5% (5 mmol/mol), and one-third remained within 0.5% (5 mmol/mol). There was a significant difference in DEPS-R scores between men and women, with women scoring higher (women, 11.0 [25th–75th percentile, 8.0–15.0]; men, 5.0 [25th–75th percentile, 2.5–11.2]; p = 0.04). Furthermore, those with overweight/obesity obtained significantly higher DEPS-R scores than those with normal weight. |

| Meltzer et al. [32] 2001 USA | Quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional. Without intervention. Eating Disorders Inventory; Body dissatisfaction, desire for thinness, and bulimia, Hb A1c, BMI n = 152. The sample consisted of 54% boys and 46% girls. The mean age of the children was 14.45 years (SD = 1.99), while the mean disease duration was 6.08 years (SD = 3.49). JBI: 8/8. | To examine the relationship between disordered eating attitudes and behaviors, BMI, and glycemic control in adolescents with T1DM. | Regarding pubertal development, 5.4% of the participants were in Tanner stage 1, 10.9% in stage 2, 14.0% in stage 3, 27.1% in stage 4, and 42.6% in stage 5. The mean HbA₁c was 9.04% (SD = 1.67), while the mean body mass index (BMI) was 22.02 kg/m2 (SD = 4.36). Regarding body dissatisfaction, the interaction between gender and BMI was found to be significant (β = 1.08, p = 0.03), suggesting that the relationship between BMI and body dissatisfaction varies by gender; however, neither gender (β = −0.54, p = 0.17) nor BMI alone (β = −0.11, p = 0.64) were significant predictors, with the model explaining 32.8% of the variance (r2 = 0.328, F = 18.24). In relation to bulimia, the interaction between age and gender was a significant predictor (β = 0.59, p < 0.001), indicating that the influence of age on bulimia symptoms varies by gender, while neither age (β = −0.15, p = 0.11) nor gender alone (β = −0.17, p = 0.16) were significant predictors, with the model explaining 20.5% of the variance (r2 = 0.205, F = 10.05). For thinness desire, the interaction between gender and body dissatisfaction was significant (β = 0.72, p = 0.01), suggesting that the impact of body dissatisfaction on thinness desire differs by gender, while neither gender (β = 0.12, p = 0.17) nor body dissatisfaction alone (β = −0.05, p = 0.85) were significant, with the model explaining 55.6% of the variance (r2 = 0.556, F = 53.82). Regarding BMI, bulimia symptoms were a significant predictor (β = 0.21, p = 0.03), with the model explaining 5.7% of the variance (r2 = 0.057, F = 6.41). Finally, in glycemic control measured by HbA₁c, disease duration (β = 0.25, p = 0.01), high scores on the bulimia subscale (β = 0.19, p = 0.05), and obesity (β = 0.16, p = 0.09) were significant predictors, with the model explaining 12.2% of the variance (r2 = 0.122, F = 4.55). |

| Olmsted et al. [33] 2008 Canada | Prospective cohort study. Body mass index (BMI) percentile, concern about weight and figure, global and appearance-based self-esteem, and depression. n = 126 girls with T1DM. At the start of the study, the participants were between 9 and 13 years old. JBI: 8/11. | To identify predictors of the onset of DEBs in adolescents with T1DM. | The study revealed that certain psychological and physical factors are closely related to the onset of DEBs, accounting for 48.2% of its occurrence. This integrative model includes concerns about weight and shape, self-esteem—both global and focused on physical appearance—BMI percentile, and depressive symptoms. When analyzing each factor separately, concerns about weight and shape, as well as self-esteem related to physical appearance, were found to be the strongest predictors of the development of DEBs, explaining 21.0% and 20.0% of the variance, respectively. Global self-esteem was also significant, although with a lesser impact, explaining 4.4% of the variance. The results showed that girls who, one or two years before starting DEBs, had a high BMI, greater body concerns, impaired self-esteem—especially related to appearance—and depressive symptoms were more likely to develop these types of behaviors. |

| Peducci et al. [34] 2018 Italy | Quantitative. Without intervention. n = 85 preadolescents and adolescents with T1DM (60% women). 60% were adolescents of mean age 13.4 ± 4.8 years. The mean age of onset of T1DM was 7.1 ± 4.0 years. JBI: 7/8. | The objective was to investigate eating patterns and eating behaviors in the adolescent population with T1DM. | The study highlighted that 43 of the patients (50.5%) reported binge eating episodes. In total, 20% of the binges were deliberate, and 17.6% suppressed or decreased their insulin dose. These were more common in patients who binge ate(χ2 = 4.58; p < 0.03). Binge eating was more common in girls than in boys. Of the 51 girls, 21.5% (or 11 girls) reported skipping insulin doses to lose weight. Of these, 10 were overweight. In contrast, only 2 boys manipulated insulin doses to do so (χ2 = 3.87; p = 0.049). Regarding Hb A1c values, there were no significant differences between girls who reported binge eating (7.8 ± 0.6%) and those who did not (7.3 ± 1.2%). |

| Rassart et al. [35] 2021 Belgium | Quantitative, descriptive, longitudinal (3 years). Without intervention. Age, sex, disease duration, treatment type, disease identity, diabetes-related distress, treatment adherence, Hb A1c. n = 276. Participants ranged in age from 14 to 15 years (mean = 19 years). 19.54% were female. JBI: 10/11. | To examine developmental trajectories of illness identity and potential associations between illness identity and diabetes-specific functioning. | Results indicated small but significant increases in acceptance (slope = 0.05, p < 0.01) and absorption (slope = 0.03, p < 0.05) and a decrease in rejection (slope = −0.08, p < 0.001). Refusal was found to negatively predict treatment adherence one year later (standardized coefficient = −0.08, p < 0.05), whereas enrichment was found to positively predict it (standardized coefficient = 0.06, p < 0.05). Furthermore, treatment adherence subsequently predicted higher levels of enrichment (standardized coefficient = 0.05, p < 0.05) and lower absorption (standardized coefficient = −0.05, p < 0.05). Both refusal and absorption predicted higher levels of diabetes-specific stress 1 year later (refusal: standardized coefficient = 0.09, p < 0.05; absorption: standardized coefficient = 0.10, p < 0.01). Stress and elevated Hb A1c levels were also found to predict increased absorption 1 year later (stress: standardized coefficient = 0.11, p < 0.01; Hb A1c: standardized coefficient = 0.06, p < 0.05). |

| Robertson et al. [36] 2020 Australia | Mixed-methods study. Without intervention. Sexual behavior and activity, body image, and anxiety, both in people with T1DM who use continuous insulin infusion (CSII) and continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) technologies, and in those who do not. n = 285 participants with T1DM. Mean age: 34.5 ± 13.3 years, with an age range of 16 to 60 years. 53% (n = 152) of respondents were women, 46% (n = 132) were men. JBI: 8/8; 10/10. | To explore the impact of external diabetes technologies on sexual behavior and activity, body image, and anxiety in adopters and non-adopters of these devices. | Despite common concerns about the visibility of technologies such as CSII, especially among women who report feeling more self-conscious about having devices attached to their bodies, research found no clear evidence that these tools have a negative impact on body image. The study revealed no significant differences in body dissatisfaction—measured using the Stunkard Figure Rating Scales—between those who use technologies such as CSII or CGM and those who do not. This absence of differences persisted even when analyzing the data by gender and age. This suggests that the decision not to adopt these technologies is not necessarily related to greater body image concerns or associated anxiety, as is sometimes assumed. In other words, although some patients with T1DM prefer to avoid visible devices for personal reasons, this preference does not appear to be linked to greater body dissatisfaction. |

| Salah et al. [37] 2022 Egypt | Qualitative, cross-sectional study. Without intervention. n = 60 adolescents with T1DM, patients of the Pediatric Diabetes Clinic at Ain Shams University Children’s Hospital between December 2020 and March 2021. The mean age of the studied adolescents with T1D was 13.35 ± 3.28 years. They were 35 females (58.3%) and 25 males (41.7%). JBI: 7/8. | The objective of the study is to compare DEB (prevalent comorbidity among adolescents with T1DM) in adolescents with T1DM receiving different therapies and correlate it with body image, glycemic control, and depressive symptoms. | Of the 60 adolescents, 14 had a poor body image (23.3%); of the remaining 46, 42 had a moderate body image (70%), and only 4 had a good body image (6.7%). Of all of them, 22 adolescents with T1DM had depression (36.7%). Another data that the study demonstrated was that no significant relationship was found between socioeconomic level and DEB (p = 0.634). |

| Sien et al. [38] 2020 Malaysia | Qualitative. Without intervention. Gender, age, relatives with T1DM. n = 15. Most participants were female (n = 11, 73.3%), while males accounted for a smaller proportion (n = 4, 26.7%). The majority were aged 13–15 years (n = 10, 66.7%), followed by those in the 16–18 age group (n = 4, 26.7%), and a smaller number in the 10–12 age group (n = 1, 6.7%). JBI: 10/10. | To determine the factors of eating disorders in adolescents with T1DM. | Regarding family history of T1DM, only n = 1, 6.7% of participants reported a family history of the disease, while the vast majority n = 14, 93.3% had no family history. One of the main themes is pressure, which comes from different sources such as school life, family, and friends. Adolescents mention that their academic load and school activities make it difficult to eat regularly, leading them to skip meals. “(Skip lunch time) because the schedule at school is quite busy, there’s a lot to do, so there’s no time to queue and buy food…” (021, female, 13 years old). Social pressure also influences their relationship with food, as criticism or comments about their food intake affect their behavior. “Because when eating with friends, they say ‘Why are you eating so much? Don’t be like this.’ But when I’m in front of the locker, I just eat how much I want and it feels like eating alone is much better…” (038, female, 14 years old). The family is also a source of pressure when they insist, they eat a certain way. “Because I think she (mother) always eat three times a day and maybe she does not understand that I’m not hungry and do not want to eat. Grandma as well. (They will tell me) you will lose weight (and that’s) unhealthy…” (007, female, 13 years old). Another theme identified is the physiological factor. Several adolescents report that their lack of appetite or fatigue influences their eating behavior, leading them to skip meals. “I skipped the morning meal because I’m not hungry, so I don’t even need to eat if I’m not hungry…” (007, female, 13 years old). Body image is a common concern, especially among adolescent girls, who report that their dissatisfaction with their bodies leads them to reduce their food intake to avoid weight gain. “Because I keep gaining weight after (I was) diagnosed with diabetes, so I just wanted my weight to be 50 kg and I am a female, so I wanted to be beautiful…” (021, female, 13 years old). Another relevant issue is the low adherence to insulin intake and dietary control. Some participants acknowledge that they struggle to control their food intake and that, despite knowing they should moderate it, they are unable to do so. “My weight gained because I keep eating too much and I just cannot stop eating…” (038, female, 14 years old). In some cases, adolescents view insulin administration as annoying and do not give it the importance it deserves. “Sometimes I forgot to take insulin…” (021, female, 13 years old). Fear is also a factor influencing the development of eating disorders. “The doctor said it’s very dangerous if I keep gaining weight, so I just wanted my weight to be 40 kg, like that only…” (038, female, 14 years old). |

| Troncone et al. [39] 2018 Italy | Quantitative, descriptive, longitudinal (5 years). Without intervention. Age, Hb A1c, age at onset, BMI, body image perception and satisfaction (Collin body silhouette), problematic eating behaviors (PEBEQ). n = 8. At baseline, the mean age of participants was 7.86 years (SD = 1.5) with a range of 5.1 to 10.06 years, while at follow-up the mean increased to 12.7 years (SD = 1.49) with a range of 10.07 to 15.08 years. JBI: 8/11. | To examine changes over a five-year period in body image accuracy and dissatisfaction, as well as relationships with DEBs, in young patients with T1DM. | HbA1c values remained relatively stable between baseline (8.16 SD = 0.94) and follow-up (7.92 SD = 1.08). The age at onset of the condition averaged 4.69 years (SD = 2.247), and disease duration increased from 2.9 years (SD = 2.44) at baseline to 7.4 years (SD = 2.23) at follow-up. A significant increase in BMI was observed, from −0.19 (SD = 1.26) at baseline to 0.97 (SD = 0.76, p < 0.001) at follow-up. Regarding weight category, the percentage of underweight participants decreased from 37.3% at baseline to 0% at follow-up, while the percentage of normal weight participants increased from 31.3% to 29.9%. An increase was seen in the proportion of overweight participants, rising from 25.4% to 43.3%, and in obesity, rising from 6% to 26.8%. At baseline and follow-up, the majority of subjects, over 70%, selected a perceived weight figure category that was thinner than their actual weight. Initially, 50.7% of participants chose an ideal figure category that was thinner than their perceived weight, regardless of their actual BMI. However, at follow-up, the majority of subjects, 52.3%, showed no discrepancy between their ideal weight and their perceived weight. An analysis of differences between mean perceived/ideal body image category and BMI weight category showed that participants tended to perceive themselves as thinner than they actually were at both baseline (t(66) = 5.131, p < 0.001) and follow-up (t(66) = 16.046, p < 0.001), and that they desired to be thinner than their actual body size at both measurements (baseline t(66) = −3.081, p ≤ 0.01; follow-up t(66) = 15.893, p < 0.001). No significant differences were found between baseline and follow-up assessments in body size estimation accuracy (F(1,66) = 1.415, p = 0.24) or body image dissatisfaction (F(1,66) = 1.499, p = 0.22), even when gender differences were considered in both comparisons (gender × misperception score interaction: F(1,65) = 0.576, p = 0.45; gender × FID score interaction: F(1,65) = 1.466, p = 0.23). No significant differences were found between men and women on the total PEBEQ score (t(65) = −0.341, p = 0.7), although body dissatisfaction was found to uniquely predict the score on this questionnaire (β = 0.272, p = 0.02), while body image misperception did not show a significant relationship with DEBs (β = 0.019, p = 0.88). |

| Troncone et al. [40] 2020 Italy | Cross-sectional study. Without intervention. The variables of interest were body image problems, eating disorder symptoms in parents, and emotional and behavioral difficulties related to the presence of DEBs in a group of adolescents with T1DM. n = 200 adolescents with T1DM. Participants ranged in age from 13.02 to 18.05 years, with a mean age of 15.24 years (standard deviation = 1.45). There were 102 boys and 98 girls. JBI: 8/8. | To examine the associations of DEBs with body image problems, parental eating disorder symptoms, and emotional and behavioral problems in adolescents with T1DM. | The main results of this study indicate that a significant proportion of Italian adolescents with T1DM present DEBs, with a prevalence of 36.5%, being more frequent in girls. Adolescents with T1DM and DEBs showed worse metabolic control, higher BMI levels, greater eating disorder symptoms, and significantly more body image problems, as well as greater emotional and behavioral difficulties compared to those without DEBs. When comparing adolescents with T1DM with a normative sample, both boys and girls with T1DM reported more eating disorder symptoms, greater internalization of social attractiveness ideals, and increased emotional and behavioral problems. A hierarchical regression analysis identified pressure to conform to social norms regarding body image and externalizing symptoms as significant predictors of BDDs in both sexes. |

| Tse et al. [41] 2012 USA | Quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional. Without intervention Age, diet reports, Hb A1c, BMI, eating problems with diabetes, attitude toward eating, treatment adherence. n = 151. Age range: 8–18 years old although the current investigation was limited to those higher or equal to 13 years old. JBI: 7/8. | To expand current knowledge on DEBs in adolescents with T1DM by examining the relationship of DEBs with dietary intake and attitudes toward healthy eating. | Forty-eight percent of participants were female. Adolescents at risk for eating disorders showed a higher prevalence of overweight/obesity compared to the low-risk group (59.1% vs. 40.9%, p = 0.01). They also had lower diet quality (HEI-2005: 45.9% vs. 53.7%, p = 0.003) and higher intakes of total fat (38.2% vs. 34.4% of total energy, p = 0.01) and saturated fat (14.0% vs. 12.2%, p = 0.007). No significant differences were observed in total energy intake (p = 0.48) or in the distribution of macronutrients from carbohydrates (p = 0.11) and proteins (p = 0.15). Regarding eating attitudes, the at-risk group showed lower self-efficacy for healthy eating (3.5 vs. 3.9, p = 0.005), greater perceived barriers to healthy eating (2.4 vs. 1.9, p < 0.001), and higher negative outcome expectations (2.9 vs. 2.1, p < 0.001). They also reported lower satisfaction with their diet (3.9 vs. 4.3, p = 0.004). Regarding diabetes management, the at-risk group showed lower adherence to treatment in both adolescent self-report (65.4 vs. 76.2, p < 0.001) and parental report (69.1 vs. 77.0, p = 0.002). They also monitored their glucose less frequently (3.2 vs. 4.7 times/day, p = 0.002) and had higher glycosylated hemoglobin levels (Hb A1c: 10.1% vs. 8.6%, p < 0.001). |

| Vanderhaegen et al. [42] 2024 Belgium | Quantitative, descriptive, longitudinal. Without intervention. Personal identity trajectory classes, levels of illness integration. n = 558. The sample consisted of n = 257 (46.06%) men and n = 301 (53.94%) women. The mean age was 18.85 years (SD = 3.24). JBI: 7/11. | To examine whether youth with T1DM belonging to different personal identity trajectories developed four dimensions of disease identity differently. | The mean age at diabetes diagnosis was 11.22 years (SD = 5.52). The majority of participants used injections (n = 437, 78.74%), while n = 118 (21.26%) used an insulin pump. An increase in acceptance over time was found (slope = 0.05, p < 0.01) and a decrease in rejection (slope = −0.08, p < 0.001). Absorption showed a slight increase (slope = 0.03, p < 0.05). Treatment adherence one year later was negatively predicted by rejection (β = −0.08, p < 0.05) and positively predicted by enrichment (β = 0.06, p < 0.05). In turn, greater treatment adherence predicted an increase in the feeling of enrichment over time (β = 0.05, p < 0.05). Both absorption and rejection in illness identity were found to predict higher levels of diabetes-specific distress one year later (rejection: β = 0.09, p < 0.05; absorption: β = 0.10, p < 0.01). Furthermore, distress and poor glycemic control predicted increased absorption in illness identity one year later (distress: β = 0.11, p < 0.01; Hb A1c: β = 0.06, p < 0.05). |

| Wilson et al. [43] 2015 England | Cross-sectional study. Without intervention. Eating disorder symptoms/attitudes/behaviors in youth with T1DM, along with diabetes-specific risk factors (BMI, glycemic control, diabetes-related family conflict) and general risk factors (dysfunctional perfectionism, self-esteem, gender, and parental eating disorder symptoms). n = 50 young people between the ages of 14 and 16 with T1DM. Of these participants, 30 were women and 20 were men. JBI: 7/8. | To examine risk factors for eating disorders in young people with T1DM. | Research shows that young people with T1DM who exhibit disordered eating attitudes and behaviors tend to have a higher BMI, poorer glycemic control, lower self-esteem, and greater family conflict. Women are more affected, especially in terms of body dissatisfaction. It is concluded that, in addition to BMI and blood glucose, it is key to consider self-esteem and family environment in assessment and therapeutic intervention. The findings revealed that adolescent girls with a higher body mass index (BMI-z) tended to report more disordered eating attitudes and behaviors than their male peers, suggesting that the impact of weight on body dissatisfaction is greater in women. In parallel, self-esteem was analyzed using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. The results showed that young people with disturbed eating attitudes and behaviors had significantly lower self-esteem than those without such disorders. This low self-esteem was not only more common in those with eating disorders, but also served as a clear marker to distinguish these young people from the rest. Taken together, the data demonstrate how body image and self-image are deeply intertwined in the context of T1DM, affecting women more intensely and highlighting the importance of self-esteem as a key factor in the detection and understanding of eating disorders. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garrido-Bueno, M.; Núñez-Sánchez, M.; García-Lozano, M.S.; Fagundo-Rivera, J.; Romero-Alvero, A.; Fernández-León, P. Effects of Body Image and Self-Concept on the Management of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121425

Garrido-Bueno M, Núñez-Sánchez M, García-Lozano MS, Fagundo-Rivera J, Romero-Alvero A, Fernández-León P. Effects of Body Image and Self-Concept on the Management of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(12):1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121425

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarrido-Bueno, Miguel, Marta Núñez-Sánchez, María Soledad García-Lozano, Javier Fagundo-Rivera, Alba Romero-Alvero, and Pablo Fernández-León. 2025. "Effects of Body Image and Self-Concept on the Management of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 13, no. 12: 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121425

APA StyleGarrido-Bueno, M., Núñez-Sánchez, M., García-Lozano, M. S., Fagundo-Rivera, J., Romero-Alvero, A., & Fernández-León, P. (2025). Effects of Body Image and Self-Concept on the Management of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 13(12), 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121425