Abstract

Background: Adolescence and young adulthood are critical periods during which psycho-emotional factors can significantly influence disease management and increase the risk of complications. This systematic review aims to examine the impact of body image, self-image, self-perception, and other psycho-emotional variables on the management of type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) in this population. Methods: This review follows the Cochrane Handbook, PRISMA 2020 guidelines and the JBI Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses. A comprehensive search was conducted across both general and discipline-specific databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Embase, CINAHL, APA PsycInfo, APA PsycArticles) between March and April 2025. The inclusion criteria focused on studies involving adolescents with T1DM that addressed relevant emotional or psychological aspects. Methodological quality was assessed using JBI tools. Data extraction was performed independently by four reviewers, with discrepancies resolved by consensus. A total of 25 studies met the inclusion criteria. Results: Body image concerns were found to be highly prevalent among adolescents and young adults with T1DM, and were associated with adverse outcomes such as disordered eating behaviors and suboptimal glycemic control. Gender differences were consistently reported, with adolescent girls and young women displaying greater body dissatisfaction and engaging more frequently in risky weight management practices, including insulin omission. Other factors, such as self-perception, diabetes-specific stress, and identity formation, also played significant roles in treatment adherence and psychosocial adaptation. Notably, this review reveals a lack of interventions specifically designed to address the psychological dimensions of T1DM. Conclusions: Body image and self-concept exert a substantial influence on T1DM management in adolescents and young adults, affecting both glycemic outcomes and psychosocial well-being. There is a pressing need for gender-sensitive and developmentally appropriate interventions that address body image, self-concept, and disease acceptance. Future research should prioritize longitudinal designs and the development and evaluation of targeted psycho-emotional support strategies.

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus comprises a group of chronic metabolic disorders characterized by impaired insulin production and elevated blood glucose levels [1]. According to the 11th edition of the IDF Diabetes Atlas (2025), approximately 589 million adults aged 20–79 are currently living with diabetes, representing 11.1% of the global population within this age group. Projections suggest that this number will increase substantially by 2050 [2].

Among its types, Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is insulin-dependent and typically diagnosed in childhood or adolescence. This early onset is associated with heightened vulnerability to both acute and chronic complications—biological, psycho-emotional, and social—during critical developmental periods [3]. It is currently estimated that approximately 9.1 million individuals worldwide are living with T1DM. Despite advances in clinical care and broader access to structured diabetes education, managing T1DM remains a significant challenge, particularly for adolescents and their families [2].

Poor glycemic control in individuals with T1DM can lead to serious biological complications, including microvascular and macrovascular alterations, which require careful the monitoring of parameters such as body mass index and continuous glucose levels [4]. On a psycho-emotional level, adolescents may develop problematic eating behaviors, identity disturbances, and negative perceptions of the disease, often manifested through dissatisfaction with body image, impaired self-concept, and diabetes-related distress [5]. At the social level, family dysfunctions and challenges in relational dynamics may further complicate disease management and everyday habits [6].

Among the different therapeutic approaches, health promotion stands out as a key strategy for empowering individuals and communities to take control of health determinants [7]. Within this framework, patient education—especially led by nurses in both hospital and community settings—is a fundamental intervention for managing chronic conditions. These educational processes aim to support people and their families in handling treatment effectively and preventing avoidable complications [7,8]. They also contribute to improving body image, treatment adherence, coping strategies, and self-care, thereby enhancing quality of life [4].

Existing research has shown that body image problems in people with T1DM are associated with several negative psychosocial and behavioral outcomes. However, most of these studies have focused on adult populations [9]. Few have examined the unique developmental and gender-specific challenges faced by adolescents and young adults living with T1DM, and no systematic review has yet been conducted to synthesize how psycho-emotional variables—specifically body image, self-image, self-perception, and identity—impact disease management in this group. This represents a critical gap in knowledge, as adolescence and young adulthood are periods when individuals are particularly sensitive to issues of physical appearance, peer comparison, autonomy, and emotional regulation, all of which may directly influence their capacity to adhere to complex treatment regimens [10].

Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze the effects of body image, self-image, self-perception, and other psycho-emotional aspects on the management of T1DM in adolescents and young adults. By identifying key psychological and social influences, this review aims to support the development of more comprehensive and developmentally appropriate interventions that address not only clinical outcomes, but also the emotional and identity-related dimensions of living with T1DM.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is a systematic review on the effects of the emotional aspects associated with T1DM on disease management. It was conducted following the Cochrane handbook, the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, and Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses [11,12,13]. A review protocol was registered in the Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/589RK). No changes were made to the information provided in the protocol.

The inclusion criteria were established based on the characteristics of the studies that could address the following research question formulated using the Population, Exposure, Outcome (PEO) framework [14]: How do emotional aspects associated with T1DM (E) in adolescents and young adults (P) influence disease management (O)?

Accordingly, studies were included if they (1) focused on adolescents (13–18 years) or young adults (19–24 years) diagnosed with T1DM, in accordance with the age classification defined by MeSH terminology, and (2) addressed the emotional, psychological, or psychosocial aspects related to the disease, such as body image, self-concept, or illness perception. No restrictions were placed on publication date, as the topic remains underexplored and limiting by date risked omitting relevant studies. Similarly, no language restrictions were applied; studies published in any language were considered, and translation tools were used as needed, in line with Cochrane recommendations [11].

Exclusion criteria included the following: studies that were not original research articles (e.g., conference abstracts, protocols, literature reviews, or meta-analyses); articles that had been retracted (verified through the Retraction Watch database); and studies that did not report data separately for adolescents and young adults when the sample included broader age ranges. Notably, no studies were excluded based on methodological quality or risk of bias at the eligibility stage; these factors were evaluated post-inclusion using the JBI critical appraisal tools [13].

Information sources were consulted between March and April 2025. These were general databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Embase) and specific nursing, psychology, and psychiatry databases (CINAHL, APA PsycInfo, APA PsycArticles). No searches were conducted on websites, organizations, or other additional resources. The search strategy was developed using the MeSH thesaurus descriptors and free terms linked to the research question. These were modified with truncations and joined with Boolean strings: (adolescen* OR teen* OR “young adult*”) AND (“type 1 diabet*” OR “diabetes mellitus type 1” OR “T1DM” OR “T1D” OR “type 1 DM”) AND (“body imag*” OR “self-imag*” OR “self-perce*”) AND (“self-manag*” OR “self-car*” OR “patient educat*” OR “diabetes manag*” OR “glycemic control” OR “treatment adheren*” OR “patient compli*”). It should be noted that NOT was changed to AND NOT in Scopus due to its technical requirements.

The search strategy applied across the selected databases generated the results is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy applied in each database.

The reference selection process was conducted independently by four peer reviewers, based on the predefined eligibility criteria, and was structured in three stages: preprocessing, screening of titles and abstracts, and full-text review [12]. In cases of disagreement, consensus was reached through discussion among reviewers, and the opinion of a fifth reviewer was sought when necessary.

Inter-rater reliability during the study selection process was assessed using Cohen’s Kappa coefficient. The calculation followed the standard formula κ = [(Po − Pe)/(1 − Pe)], where Po represents the observed agreement and Pe represents the agreement expected by chance. Of the 80 full-text articles assessed for eligibility, reviewers agreed on 74, resulting in Po = 0.925. The expected chance agreement was Pe = 0.375. Substituting this into the formula yields κ = [(0.925 − 0.375)/(1 − 0.375)] = (0.55/0.625) = 0.88.

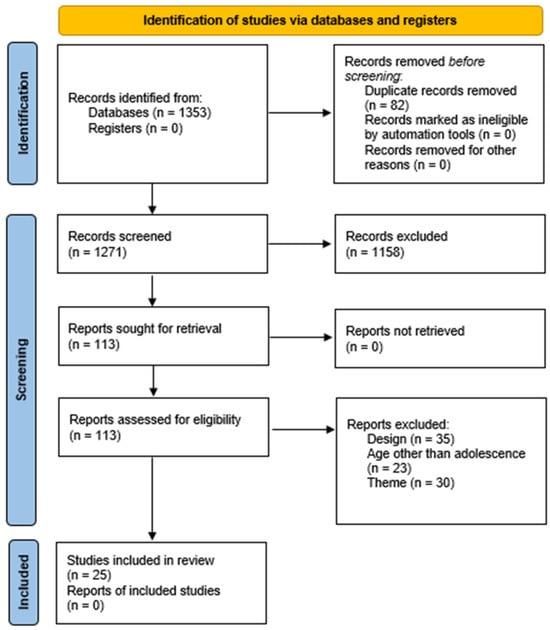

The reviewers used Zotero (version 7.0.15) for reference management, and the selection process is visually represented using a PRISMA 2020 flowchart [12] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Once the literature search was completed and the studies to be included in the present systematic review were selected, the JBI critical appraisal tool [13] was independently applied by four peer reviewers. This process helped identify the potential methodological biases present in the included studies and informed the interpretation of the results, considering the specific characteristics and limitations of each study design. For this review, the JBI checklists for analytical cross-sectional and longitudinal studies [15], randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [16], and qualitative research [17] were used. These critical appraisal checklists are part of the JBI systematic review methodology and are designed to assess the methodological quality of studies and the extent to which potential sources of bias have been addressed in their design, conduct, and analysis. Each checklist consists of a series of questions to be answered with “Yes”, “No”, “Unclear”, or “Not applicable”, followed by an overall appraisal to determine whether the study should be included, excluded, or if further information is required.

Common domains assessed across the checklists include the validity and reliability of exposure or treatment measurement, the identification and management of confounding factors, the validity and reliability of outcome measurement, and the appropriateness of the statistical analysis employed. The checklists are personalized to specific study designs; for example, the analytical cross-sectional checklist includes items on clearly defined inclusion criteria and detailed descriptions of participants and settings, the cohort study checklist addresses group similarity and follow-up strategies, the RCT checklist focuses on the randomization procedures and blinding of participants and personnel, and the qualitative research checklist assesses data analysis, synthesis, and presentation of findings, as well as transparency in the reporting of the methodological approach [13,15,16,17].

Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussions, and the opinion of a fifth reviewer was sought when consensus could not be reached. Inter-rater reliability was high (κ = 0.90), indicating almost perfect agreement according to the Landis and Koch classification [18].

The data extraction process was carried out independently by four peer reviewers using Microsoft Excel (version 2016). In cases of disagreement, consensus was reached through discussion among reviewers, and a fifth reviewer was consulted when necessary. Inter-rater reliability was high (κ = 0.92), indicating almost perfect agreement according to the Landis and Koch classification [18]. The data collected and recorded for each study included the following: (a) reference, authorship, year, and region of publication; (b) study design, intervention characteristics, variables examined, sample size, and JBI appraisal score; (c) study objective; and (d) findings related to the psycho-emotional aspects of T1DM. Confounding information was intentionally excluded from the analysis. In this review, one example of such confounding was the failure to disaggregate outcomes specific to adolescents when results were reported for broader age ranges that included, but did not isolate, adolescent participants.

A narrative synthesis was conducted using a conceptual domain-based grouping method. These domains were developed inductively based on recurring patterns and central topics across the studies, and they were subsequently refined through team discussions and consensus. The final domains used to structure the results were as follows: (1) the characteristics of the included studies; (2) the prevalence and correlates of body image concerns and self-perception; (3) the impact of body image concerns and self-perception on glycemic control and T1DM management; (4) T1DM-specific stress, identity, and coping mechanisms; and (5) intervention strategies and gaps related to the psycho-emotional aspects of T1DM management.

3. Results

A total of 25 studies were chosen for this systematic review (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of selected articles.

3.1. Methods and General Characteristics of the Studies

The included studies were conducted across various countries, including the United States [19,23,31,32,41], Italy [34,39,40], Belgium [35,42], Australia [27,36], Germany [28,30], the United Kingdom [21,43], the Netherlands [25], Malaysia [38], Sweden [20], Canada [33], Taiwan [22], Egypt [37], Palestine [26], South Korea [29], and Ethiopia [24].

The 25 studies were published across several years, starting in 1999 [21] and ending with the most recent publication in 2024 [42]. The study with the largest sample size was Vanderhaegen et al. [42] (n = 558), while the smallest sample size was found in Jeong et al. [29] (n = 14).

Regarding the quantitative design, this research includes twelve cross-sectional [19,22,24,25,26,27,32,34,37,40,41,43], eight longitudinal studies [21,28,30,31,33,35,39,42], and one randomized controlled trial [20]. On the other hand, three qualitative studies have been included [23,29,38]. Finally, the research includes one mixed-methods study [36].

The methodological quality assessment using JBI tools revealed overall moderate-to-high rigor across the included studies. Most cross-sectional studies scored between 7 and 8 out of 8, with several (e.g., [32,36,40]) achieving perfect scores. Longitudinal studies showed more variability, with scores ranging from 6 to 10 out of 11; Reference [35] stood out with the highest score, while others had notable limitations. The only randomized controlled trial [20] scored 9 out of 13, suggesting good quality. All of the qualitative studies included scored 10 out of 10, indicating excellent methodological consistency (Supplementary Tables S1–S4).

3.2. Prevalence, Correlates, and Gender Differences in Body Image Concerns, Emotional Responses, and Self-Perception

Several studies have explored the frequency and reasons behind body image concerns in adolescents and young adults with T1DM [25,32,39]. A significant interaction was found between gender and body mass index on body dissatisfaction, as well as between gender and body dissatisfaction on the desire for thinness [32]. Similarly, it was observed that most young people with T1DM tended to perceive themselves as thinner than they were and desired to be even thinner, and that body dissatisfaction was a unique predictor of problematic eating behaviors [39]. This desire for thinness and body dissatisfaction are confirmed in cross-sectional studies, such as the one by Eilander et al. [25], where almost half of adolescents with T1DM reported concerns about their body image and weight, and body dissatisfaction was significantly related to disturbed eating behaviors.

The influence of gender is consistently highlighted [19,26,32,38]. In addition to its significant interaction with other variables on body dissatisfaction and desire for thinness [32], other studies found that body image was a frequent concern among adolescents with T1DM, leading them to reduce food intake [38], and even found that a significant percentage of adolescent girls with T1DM, compared to those without the pathology, omitted or reduced their insulin dose to lose weight and were more likely to report body dissatisfaction [19]. This finding is reinforced by the study by Olmsted et al. [33], which identified that concern about weight and figure, as well as self-esteem based on appearance, were strong predictors of the development of eating disorders in adolescent girls with T1DM.

Other associated factors include concern about medical devices [23] and the greater evaluative salience of appearance in younger adults with T1DM [27]. In addition, other studies observed that adolescents with T1DM with higher body mass indexes tended to manifest disordered attitudes towards eating, with a greater impact on women [43], and these studies also confirmed a high prevalence of eating disorders in adolescents with T1DM, being more frequent in girls and significantly associated with body image problems [40]. More recent studies found a high prevalence of body dissatisfaction associated with eating disorders [24] and reported a significant proportion of adolescents with T1DM with poor body image [37].

3.3. Impact of Body Image Concerns and Self-Perception on Glycemic Control and T1DM Management

Several studies have shown a connection between body image concerns and diabetes management [25,28,32]. Elevated scores on the bulimia subscale were significant predictors of Hb A1c test [32]. Similarly, adolescents with eating disorders were found to have significantly higher Hb A1c levels and lower self-care confidence, showing impaired disease management [25]. At the family level, it was also found that, in single adolescents, a worse perception of body image mediated the relationship between a negative family climate and impaired glycemic control [28].

Insulin restriction, as a behavior associated with body image concerns, also negatively impacts glycemic control [21,27]. Younger adults who reported restricting insulin to control weight showed higher Hb A1c [27], with women being more affected [21].

Self-perception also plays a relevant role on glycemic control and T1DM management [22,26,31,40,43]. Studies found a negative correlation between perceived health and Hb A1c, as well as between a sense of coherence and Hb A1c in adolescents with T1DM, suggesting that better self-perception and sense of coherence are associated with better glycemic control [26] and that higher Hb A1c was observed in overweight/obese participants who were also at higher risk of disordered eating [31]. Other studies indicated that young people with T1DM who reported disordered attitudes towards eating tended to have worse glycemic control [40,43], so much so that greater variability in Hb A1c levels was associated with a higher risk of eating disorders in this population [22].

3.4. T1DM-Specific Stress, Identity, and Coping Mechanisms

Other studies have explored the psychosocial burden of living with this condition, particularly in relation to identity [23,35,42]. Adolescents with T1DM reported feelings of frustration and exhaustion due to the constant monitoring, even leading to the denial or refusal of treatment as a coping mechanism. However, a process of acceptance and adaptation over time was also observed [23]. Other studies found that rejection of the T1DM identity negatively predicted treatment adherence, and both rejection and absorption were associated with higher levels of disease-specific stress [35]. Stress and elevated Hb A1c levels were also found to predict the increased absorption of the disease identity [42].

Regarding coping mechanisms, a positive correlation was found between perceived health and sense of coherence in adolescents with T1DM [26], as well as a higher positive self-concept in those adolescents and young adults with optimal glycemic control [30]. Another study highlighted the strong desire of young adults with T1DM to be recognized as individuals beyond their diagnosis, experiencing frustration when their identity was reduced to their medical condition and expressing a longing for “normality” that sometimes led to self-care avoidance and feelings of embarrassment when managing diabetes in public [29].

3.5. Interventions Strategies and Gaps in the Psycho-Emotional Aspects of T1DM Management

Regarding interventions, one based on the Guided Self-Determination-Young model improved glycemic control after 12 months in adolescents initiating continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion [20]. Another intervention based on insulin pump therapy was associated with a lower prevalence of eating disorders after several months of study [31]. These studies suggest that patient- and technology-centered interventions could have benefits regarding both metabolic and eating behavior aspects.

4. Discussion

This systematic review examines the impact of body image and self-concept on the treatment of T1DM, particularly among adolescents and young adults. The findings suggest that these populations are especially vulnerable to challenges related to body image perception, DEBs, and the integration of disease identity. These factors negatively influence glycemic control and psychosocial adjustment.

4.1. Identity Development and T1DM Management

Adolescence and early adulthood are periods of increased sensitivity due to asynchronous neurocognitive development, increased social demands, and the emergence of mental health problems [44]. During these stages, the construction of self-concept and the integration of a chronic disease into one’s personal identity are critical for the effective management of T1DM [23]. Longitudinal studies indicate that diabetes-related identity tends to evolve through phases of rejection, absorption, and acceptance. Rejection of this identity has been associated with a lower level of adherence to treatment and a higher level of diabetes-related distress, while acceptance and a sense of personal growth are linked to better adherence and reduced stress.

Managing T1DM imposes a considerable psychosocial burden, particularly when the self-definition process overlaps with a crucial stage of identity formation [45]. Qualitative studies have shown that young people with T1DM perceive the condition as a persistent disruption of daily life and a continuous source of stress, affecting not only their quality of life, but also their self-image and perception of their body.

The visibility of medical devices, such as insulin pumps or continuous glucose monitors, can contribute to discomfort and social stigmatization, particularly in school or social settings. This discomfort can lead to avoidant behaviors, including temporarily removing devices or refraining from using them in public, which compromises disease management and reinforces a sense of “abnormality” that negatively affects self-perception [46].

4.2. Eating Behaviors and Glycemic Control

One of the most concerning patterns identified in this review is the intentional restriction or omission of insulin as a weight control strategy, predominantly reported among young women with T1DM. This behavior, which is clinically dangerous and psychologically distressing, is associated with poorer glycemic control and a greater risk of microvascular complications [47]. The motivations that motivate them often include body dissatisfaction, social pressure, and a desire for physical normality, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions that address these psychosocial aspects.

The relationship between body image, DEBs, and glycemic control is complex and multifaceted [40]. Several studies have confirmed that body dissatisfaction is a significant predictor of DEBs in adolescents with T1DM. These behaviors, which range from dietary restriction to binge eating, have detrimental effects on glycemic outcomes. Potential mechanisms include emotional dysregulation, low self-esteem, and social pressures with respect to physical appearance. Furthermore, recent research suggests that variability in Hb A1c levels, in addition to average levels alone, is also linked to an increased risk of eating disorders, pointing to a dimension of metabolic instability that is associated with psychological distress.

Although most of the included studies focused on the psychosocial factors influencing eating behaviors and glycemic control in adolescents with T1DM, it is important to situate these behaviors within the broader context of global nutritional transitions. While the findings from Ahmad and Yuasa are not specific to T1DM, they highlight how rapid nutritional shifts—characterized by sedentary lifestyles and poor-quality diets—can contribute to metabolic risk and unhealthy weight gain beginning early in life. Such environments may exacerbate challenges in glycemic control for youth with T1DM, particularly when disordered eating patterns and body dissatisfaction are present [48].

4.3. Gender Differences

The findings of this review consistently highlight the critical role of gender in the manifestation of concerns about body image and the prevalence of DEBs among people with T1DM [49]. Adolescent girls and young women with T1DM exhibit higher levels of body dissatisfaction, a stronger desire for thinness, and a greater tendency to engage in risky weight management behaviors, such as deliberately reducing or skipping insulin doses. This pattern has been documented in multiple quantitative and qualitative studies, including both cross-sectional and longitudinal designs.

From a sociocultural perspective, these gender differences can be understood within the framework of normative beauty ideals, which disproportionately impact women, especially during adolescence, a developmental stage marked by intensified social pressure to conform to esthetic standards [10]. Internalization of these ideals can create a profound conflict between optimal management of diabetes, which often involves visible medical devices and treatment-induced changes in body weight, and the desire to conform to the social standards of an acceptable or desirable body [50].

This analysis gains additional relevance when contextualized within the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development of the United Nations, particularly Goal 3 (Good Health and Well-being) and Goal 5 (Gender Equality) [51]. Neglecting the influence of gender in the management of chronic diseases such as T1DM not only jeopardizes the physical and mental health of women, but also perpetuates structural disparities in access, quality of care, and health equity [52,53].

4.4. Influence of Family and Social Environment

Social and familial environment also plays a critical role in these dynamics. A negative family environment, as well as the perceived stigma related to the use of medical devices, has been associated with poorer body image and lower self-concept, which may indirectly affect glycemic control [8,54]. On the contrary, a positive perception of health and a high sense of coherence have been associated with better metabolic outcomes, suggesting that interventions targeting these factors could prove beneficial.

Self-esteem, particularly in relation to physical appearance, has emerged as a significant risk factor for the development of body dissatisfaction in adolescents with T1DM [55]. Studies included in this review report that low self-esteem correlates with increased weight-related concerns and negative body image, which, in turn, can hamper treatment adherence.

Additionally, longitudinal studies have shown that a negative family climate characterized by conflict, emotional unavailability, or excessive control over treatment can directly affect perceptions of body image in adolescents. In such cases, body image functions as a mediator variable between family dynamics and glycemic control, further highlighting its clinical relevance in the comprehensive treatment of T1DM.

4.5. Limitations and Strengths

Despite the valuable insights provided by this review, it is important to recognize several limitations inherent in the included studies. A large proportion of the evidence is derived from cross-sectional designs, which limits the ability to establish causal relationships between body image concerns and diabetes management outcomes. Many studies also relied on self-reported data, which are subject to recall bias and social desirability effects. Furthermore, longitudinal studies remain scarce, impeding our complete comprehension of the long-term psychosocial trajectories associated with T1DM in adolescence and young adulthood.

In addition to methodological limitations, broader contextual factors should be considered. Cultural differences in body image ideals, health beliefs, and gender norms may influence how adolescents perceive themselves and manage their condition. These variables are often underreported or not accounted for in the literature, potentially limiting the generalizability of findings across different sociocultural contexts. In this way, future research should prioritize longitudinal, culturally sensitive designs that can capture the complex, evolving relationship between self-concept and chronic illness management.

Despite these limitations, this review has several strengths. It is the first to systematically synthesize evidence on the intersection between body image, self-concept, and disease management specifically in adolescents and young adults with T1DM. The utilization of a comprehensive search strategy, adherence to rigorous methodological standards (PRISMA, Cochrane Handbook, and JBI Checklist), and the inclusion of both qualitative and quantitative evidence provide a robust and multidimensional comprehension of the topic. This integrative perspective enhances the clinical relevance of the findings and supports the design of more targeted and developmentally appropriate interventions.

4.6. Future Perspectives

4.6.1. The Role of Technology in Psychological Support

The increasing use of advanced technologies in the management of T1DM, such as continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion and continuous glucose monitoring, has significantly transformed the experience of living with this condition. A peer-reviewed study suggests that these technologies do not negatively impact body image, at least in the short term. However, it is imperative to conduct longitudinal research focused on vulnerable subgroups to fully understand their influence on body perception, adherence to treatment, and mental health.

In this context, the emerging use of tools and digital platforms based on artificial intelligence (AI) presents a unique opportunity to monitor, predict, and intervene in a personalized manner when signs of psychological risk arise, such as the development of DEBs or the rejection of treatment [56]. The integration of AI with clinical and psychosocial data could enable automated early detection, thus improving clinical response and facilitating more accurate and timely interventions [57].

4.6.2. Media and Social Media Influence

Although the impact of media and social networks on body image has been widely documented in the general population [58], its specific influence on young individuals with T1DM is still lacking evidence. Digital platforms, although potentially a source of esthetic pressure and social comparison, can also serve as educational and health promotion tools if strategically used [59].

Digital campaigns, influencers living with T1DM, virtual support groups, and positive narratives on social media could play a meaningful role in reducing stigma, normalizing the use of medical devices, and improving self-concept among young people with diabetes [53,60].

4.6.3. The Importance of Qualitative Approaches

Given the prevalence of quantitative studies, qualitative research emerges as an essential tool for capturing the subjective experience of living with T1DM, particularly in relation to body image, self-concept, and coping strategies [61]. The qualitative studies reviewed revealed powerful narratives that involve frustration, shame, the desire for normalcy, and avoidance behaviors that shape the daily lives of many individuals with this condition.

These studies give attention to personal experiences, help identify psychosocial barriers often overlooked in biomedical models, and shed light on the emotional impact of factors such as the use of visible medical devices or body-related social commentary. Qualitative approaches are also critical for exploring the experiences of less represented groups (e.g., men with DEBs, LGBT individuals, ethnic minorities) who are frequently excluded from large-scale population studies [62].

Despite significant advances in the technological and metabolic management of T1DM, psycho-emotional care remains an often-neglected area, especially in relation to body image and self-perception. This review indicates that, although some preliminary efforts have been made, there is a notable lack of interventions specifically targeting the psychological dimensions of T1DM.

Although patient-centered models, such as Guided Self-Determination Young, have shown promise in improving glycemic control and adherence to treatment, their impact on body image, self-esteem, and DEB prevention has not been thoroughly evaluated [20]. Based on these findings, there is a clear need to foster the development and evaluation of interventions that directly and explicitly address concerns related to physical appearance, self-concept, and acceptance of disease.

Potential strategies include adapted cognitive behavioral therapy for people with T1DM, acceptance and commitment therapy focusing on the integration of disease identity, educational programs that combine body image literacy with diabetes management, and the promotion of peer emotional support networks [63]. These interventions should be gender and developmentally sensitive and should preferably be evaluated using randomized controlled trials with long-term follow-ups [64].

4.6.4. Cross-Cultural Perspectives

As this review incorporates studies conducted in diverse sociocultural settings—including the USA, Italy, Belgium, Malaysia, Egypt, and Palestine—the need for cross-cultural research becomes evident. Such research should explore how social norms, cultural values, and healthcare systems shape body image, self-esteem, and diabetes-related behaviors.

Concerns related to body image and weight, as well as coping strategies, are not universally experienced; stigma can take different forms depending on the cultural context, and local beauty ideals can exert varying levels of pressure [10]. Therefore, comparative studies are essential to identifying cultural similarities and differences in disease experience and to adapting clinical interventions accordingly.

A cross-cultural lens is also crucial for the development of culturally sensitive assessment tools and relevant educational programs that reflect local realities, avoiding the uncritical application of models developed in high-income countries without appropriate adaptation or validation [65].

5. Conclusions

This systematic review aimed to analyze the effects of body image, self-image, self-perception, and other psycho-emotional aspects on the management of T1DM in adolescents and young adults. The evidence gathered from 25 studies reveals the multifactorial and interrelated impact of these variables on both glycemic control and the psychosocial well-being of young individuals with T1DM.

Concerns about body image were found to be highly prevalent, particularly among adolescent girls and young women, and were frequently associated with DEBs, including insulin omission as a method of weight control. These behaviors, in turn, contribute to poorer glycemic control and increased risk of complications. Self-concept and self-perception also emerged as critical factors influencing adherence to treatment and adjustment to the disease, with low self-esteem and negative self-image correlating with worse clinical and emotional outcomes.

Moreover, identity issues, especially difficulties in integrating the disease into one’s self-concept, were linked to denial, treatment nonadherence, and emotional distress. Adolescents who demonstrated higher levels of disease acceptance tended to show better adherence and improved metabolic outcomes, whereas those who internalized stigma or rejected their illness experienced higher psychological burden.

These findings emphasize the need for clinical approaches that go beyond metabolic control, addressing the emotional, cognitive, and social dimensions of diabetes management. Interventions should be gender-sensitive and developmentally personalized, incorporating body image work, emotional regulation strategies, and self-concept strengthening into routine diabetes care. Nurses, psychologists, and interdisciplinary teams have a key role in designing and delivering these integrative interventions.

Finally, future research should focus on longitudinal studies to better understand the causal relationships and temporal dynamics between psycho-emotional factors and diabetes outcomes, as well as focusing on evaluating the efficacy of psychosocial interventions that target body image, self-perception, and disease acceptance in this vulnerable population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare13121425/s1, Table S1. Scores of analytical cross-sectional studies; Table S2. Scores of longitudinal studies; Table S3. Score of randomized controlled trial; Table S4. Scores of qualitative research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.-B., M.N.-S., M.S.G.-L., J.F.-R., A.R.-A. and P.F.-L.; Data curation, M.G.-B., M.N.-S., M.S.G.-L., J.F.-R., A.R.-A. and P.F.-L.; Formal analysis, M.G.-B., M.N.-S., M.S.G.-L., J.F.-R., A.R.-A. and P.F.-L.; Investigation, M.G.-B., M.N.-S., M.S.G.-L., J.F.-R., A.R.-A. and P.F.-L.; Methodology, M.G.-B., M.N.-S., M.S.G.-L., J.F.-R., A.R.-A. and P.F.-L.; Project administration, M.G.-B., J.F.-R. and P.F.-L.; Resources, M.G.-B., M.N.-S., M.S.G.-L., J.F.-R., A.R.-A. and P.F.-L.; Software, M.G.-B., M.N.-S., M.S.G.-L., J.F.-R., A.R.-A. and P.F.-L.; Supervision, M.G.-B., M.N.-S., M.S.G.-L., J.F.-R., A.R.-A. and P.F.-L.; Validation, M.G.-B., M.N.-S., M.S.G.-L., J.F.-R., A.R.-A. and P.F.-L.; Visualization, M.G.-B., M.N.-S., M.S.G.-L., J.F.-R., A.R.-A. and P.F.-L.; Writing—original draft, M.G.-B., M.N.-S., M.S.G.-L., J.F.-R., A.R.-A. and P.F.-L.; Writing—review and editing, M.G.-B., M.N.-S., M.S.G.-L., J.F.-R., A.R.-A. and P.F.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available within this article and Supplementary Files.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript (displayed in alphabetical order):

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| DEB | Disordered eating behavior |

| HbA1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| LGBT | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender |

| PEO | Person, Exposure, Outcome |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| T1DM | Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus |

References

- Garrido-Bueno, M.; Pabón-Carrasco, M.; Jiménez-Picón, N.; Romero-Castillo, R. Health Promotion in Glycemic Control and Emotional Well-Being of People with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas. 10th Edition. Available online: https://idf.org/about-diabetes/diabetes-facts-figures/ (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care 2021, 45, S17–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yapanis, M.; James, S.; Craig, M.E.; O’Neal, D.; Ekinci, E.I. Complications of Diabetes and Metrics of Glycemic Management Derived from Continuous Glucose Monitoring. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, e2221–e2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosak, L.; Stiglic, G. Cognitive and Emotional Perceptions of Illness in Patients Diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Healthcare 2024, 12, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prell, T.; Stegmann, S.; Schönenberg, A. Social Exclusion in People with Diabetes: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Results from the German Ageing Survey (DEAS). Sci. Rep. (Nat. Publ. Group) 2023, 13, 7113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Therapeutic Patient Education: Continuing Education Programmes for Health Care Providers in the Field of Prevention of Chronic Diseases: Report of a WHO Working Group; European Health 21 target 18, Developing Human resources for Health; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1998; ISBN 978-92-890-1298-0. [Google Scholar]

- Santa Cruz-Álvarez, P.; Ruiz-Trillo, C.A.; Pérez-Morales, A.; Cortés-Lerena, A.; Gamero-Dorado, C.; Garrido-Bueno, M. Educación Terapéutica Enfermera Sobre El Control Glucémico y Bienestar Emocional En Adolescentes Con Diabetes Mellitus de Tipo 1 Durante La Transición Hospitalaria. Endocrinol. Diabetes Y Nutr. 2025, 72, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inns, S.J.; Chen, A.; Myint, H.; Lilic, P.; Ovenden, C.; Su, H.Y.; Hall, R.M. Comparative Analysis of Body Image Dissatisfaction, Depression, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adults with Type 1 Diabetes: A Case-Control Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino, M.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F.; Rubio-Zarapuz, A.; Villanueva-Tobaldo, C.V.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Body Perceptions and Psychological Well-Being: A Review of the Impact of Social Media and Physical Measurements on Self-Esteem and Mental Health with a Focus on Body Image Satisfaction and Its Relationship with Cultural and Gender Factors. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.4 (Updated August 2023); Cochrane: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JBI. 2025 JBI Critical Appraisal Tools|JBI. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Tawfik, G.M.; Dila, K.A.S.; Mohamed, M.Y.F.; Tam, D.N.H.; Kien, N.D.; Ahmed, A.M.; Huy, N.T. A Step by Step Guide for Conducting a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Simulation Data. Trop. Med. Health 2019, 47, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufunaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetc, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al. Systematic Reviews of Etiology and Risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., Jordan, Z., Eds.; JBI: Kochi, India, 2024; ISBN 978-0-6488488-2-0. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, T.H.; Stone, J.C.; Sears, K.; Klugar, M.; Tufanaru, C.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. The Revised JBI Critical Appraisal Tool for the Assessment of Risk of Bias for Randomized Controlled Trials. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative Research Synthesis: Methodological Guidance for Systematic Reviewers Utilizing Meta-Aggregation. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackard, D.M.; Vik, N.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Schmitz, K.H.; Hannan, P.; Jacobs, D.R. Disordered Eating and Body Dissatisfaction in Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes and a Population-Based Comparison Sample: Comparative Prevalence and Clinical Implications. Pediatr. Diabetes 2008, 9, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brorsson, A.L.; Leksell, J.; Andersson Franko, M.; Lindholm Olinder, A. A Person-centered Education for Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes—A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatr. Diabetes 2019, 20, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryden, K.S.; Neil, A.; Mayou, R.A.; Peveler, R.C.; Fairburn, C.G.; Dunger, D.B. Eating Habits, Body Weight, and Insulin Misuse. A Longitudinal Study of Teenagers and Young Adults with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 1999, 22, 1956–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.-C.; Chou, Y.-Y.; Pan, Y.-W.; Ou, T.-Y.; Tsai, M.-C. Correlates of Disordered Eating and Insulin Restriction Behavior and Its Association with Psychological Health in Taiwanese Youths with Diabetes Mellitus. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commissariat, P.V.; Kenowitz, J.R.; Trast, J.; Heptulla, R.A.; Gonzalez, J.S. Developing a Personal and Social Identity with Type 1 Diabetes During Adolescence. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, L.; Haile, D.; Egata, G. Disordered Eating Behaviours and Body Shape Dissatisfaction among Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes: A Cross Sectional Study. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilander, M.M.A.; de Wit, M.; Rotteveel, J.; Aanstoot, H.J.; Bakker-van Waarde, W.M.; Houdijk, E.C.A.M.; Nuboer, R.; Winterdijk, P.; Snoek, F.J. Disturbed Eating Behaviors in Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. How to Screen for Yellow Flags in Clinical Practice? Pediatr. Diabetes 2017, 18, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elissa, K.; Bratt, E.-L.; Axelsson, A.B.; Khatib, S.; Sparud-Lundin, C. Self-Perceived Health Status and Sense of Coherence in Children with Type 1 Diabetes in the West Bank, Palestine. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2020, 31, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawlik, N.R.; Elias, A.J.; Bond, M.J. Appearance Investment, Quality of Life, and Metabolic Control Among Women with Type 1 Diabetes. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2016, 23, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, A.C.; Seiffge-Krenke, I.; Laursen, B. Body Image Mediates Negative Family Climate and Deteriorating Glycemic Control for Single Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. Fam. Syst. Health 2015, 33, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.M.; Quinn, L.; Kim, N.; Martyn-Nemeth, P. Health-Related Stigma in Young Adults with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2018, 56, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyckx, K.; PHD; Seiffge-Krenke, I. PHD Continuity and Change in Glycemic Control Trajectories from Adolescence to Emerging Adulthood: Relationships with Family Climate and Self-Concept in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowitz, J.T.; Alleyn, C.A.; Phillips, R.; Muir, A.; Young-Hyman, D.; Laffel, L.M.B. Disordered Eating Behaviors in Youth with Type 1 Diabetes: Prospective Pilot Assessment Following Initiation of Insulin Pump Therapy. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2013, 15, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, L.; Johnson, S.; Prine, J.; Banks, R.; Desrosiers, P.; Silverstein, J. Disordered Eating, Body Mass, and Glycemic Control in Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmsted, M.P.; Colton, P.A.; Daneman, D.; Rydall, A.C.; Rodin, G.M. Prediction of the Onset of Disturbed Eating Behavior in Adolescent Girls with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 1978–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peducci, E.; Mastrorilli, C.; Falcone, S.; Santoro, A.; Fanelli, U.; Iovane, B.; Incerti, T.; Scarabello, C.; Fainardi, V.; Caffarelli, C.; et al. Disturbed Eating Behavior in Pre-Teen and Teenage Girls and Boys with Type 1 Diabetes. Acta Bio-Medica Atenei Parm. 2019, 89, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassart, J.; Oris, L.; Prikken, S.; Goethals, E.R.; Raymaekers, K.; Weets, I.; Moons, P.; Luyckx, K. Illness Identity and Adjusting to Type I Diabetes: A Four-Wave Longitudinal Study. Health Psychol. 2021, 40, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, C.; Lin, A.; Smith, G.; Yeung, A.; Strauss, P.; Nicholas, J.; Davis, E.; Jones, T.; Gibson, L.; Richters, J.; et al. The Impact of Externally Worn Diabetes Technology on Sexual Behavior and Activity, Body Image, and Anxiety in Type 1 Diabetes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2020, 14, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salah, N.; Hashem, M.; Abdeen, M. Body Image Perception among Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus; Relation to Glycemic Variability, Depression and Disordered Eating Behaviour. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2024, 97, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sien, P.L.M.; Jamaludin, N.I.A.; Samrin, S.N.A.; Shanita, N.S.; Ismail, R.; Zaini, A.A.; Sameeha, M.J. Causative Factors of Eating Problems among Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: A Qualitative Study. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncone, A.; Cascella, C.; Chianese, A.; Galiero, I.; Zanfardino, A.; Confetto, S.; Perrone, L.; Iafusco, D. Changes in Body Image and Onset of Disordered Eating Behaviors in Youth with Type 1 Diabetes over a Five-Year Longitudinal Follow-Up. J. Psychosom. Res. 2018, 109, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troncone, A.; Cascella, C.; Chianese, A.; Zanfardino, A.; Piscopo, A.; Borriello, A.; Casaburo, F.; del Giudice, E.M.; Iafusco, D. Body Image Problems and Disordered Eating Behaviors in Italian Adolescents with and Without Type 1 Diabetes: An Examination With a Gender-Specific Body Image Measure. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 556520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, J.; Nansel, T.R.; Haynie, D.L.; Mehta, S.N.; Laffel, L.M.B. Disordered Eating Behaviors Are Associated with Poorer Diet Quality in Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 1810–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderhaegen, J.; Raymaekers, K.; Prikken, S.; Claes, L.; Van Laere, E.; Campens, S.; Moons, P.; Luyckx, K. Personal and Illness Identity in Youth with Type 1 Diabetes: Developmental Trajectories and Associations. Health Psychol. 2024, 43, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.E.; Smith, E.L.; Coker, S.E.; Hobbis, I.C.A.; Acerini, C.L. Testing an Integrated Model of Eating Disorders in Paediatric Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Pediatr. Diabetes 2015, 16, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on the Neurobiological and Socio-behavioral Science of Adolescent Development and Its Applications; Backes, E.P.; Bonnie, R.J. Adolescent Development. In The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bombaci, B.; Torre, A.; Longo, A.; Pecoraro, M.; Papa, M.; Sorrenti, L.; La Rocca, M.; Lombardo, F.; Salzano, G. Psychological and Clinical Challenges in the Management of Type 1 Diabetes during Adolescence: A Narrative Review. Children 2024, 11, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanning, M.S.; Tanenbaum, M.L.; Wong, J.J.; Hood, K.K. Barriers to Continuous Glucose Monitoring in People with Type 1 Diabetes: Clinician Perspectives. Diabetes Spectr. 2020, 33, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beam, A.B.; Wiebe, D.J.; Berg, C.A. Insulin Restriction, Emotion Dysregulation, and Depressive Symptoms in Late Adolescents with Diabetes. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2021, 46, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, I.; Yuasa, M. Childhood Obesity in South-Asian Countries: A Systematic Review (Causes and Prevention). Juntendo Med. J. 2018, 64, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araia, E.; King, R.M.; Pouwer, F.; Speight, J.; Hendrieckx, C. Psychological Correlates of Disordered Eating in Youth with Type 1 Diabetes: Results from Diabetes MILES Youth-Australia. Pediatr. Diabetes 2020, 21, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Morros, A.; Berenguera, A.; Millaruelo, L.; Buil-Cosiales, P.; Gomez Garcia, C.; Cos, X.; Ávila Lachica, L.; Artola, S.; Millaruelo, J.M.; Mauricio, D.; et al. Impact of Gender on Patient Experiences of Self-Management in Type 2 Diabetes: A Qualitative Study. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2024, 18, 1885–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN DESA. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ciarambino, T.; Crispino, P.; Leto, G.; Mastrolorenzo, E.; Para, O.; Giordano, M. Influence of Gender in Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complication. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Bueno, M.; Dorcé, N.; Zaldívar Fernández, M.C. Narrativas de Género Sobre Diabetes Mellitus En Foros Online: Un Proyecto de Investigación Etnográfica Digital. In Innovación en Salud: Nuevas Estrategias Para la Enseñanza y la Investigación; del Mar Simón Márquez, M., Barragán Martín, A.B., Molina Moreno, P., Gázquez Linares, J.J., Martínez Casanova, E., Eds.; Dialnet: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2025; ISBN 979-13-990275-3-2. [Google Scholar]

- Azar, S.; Maroun Abou Jaoude, N.; Kędzia, A.; Niechciał, E. Barriers to Type 1 Diabetes Adherence in Adolescents. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, A.; Tanveer, F.; Sharif, F. Sadia Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Symptoms and Its Associated Risk Factors in Touchscreen Tablet Computer Users. Rawal Med. J. 2020, 45, 382–384. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchison, D. AI-Readiness in the Eating Disorders Field. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alowais, S.A.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Alsuhebany, N.; Alqahtani, T.; Alshaya, A.I.; Almohareb, S.N.; Aldairem, A.; Alrashed, M.; Bin Saleh, K.; Badreldin, H.A.; et al. Revolutionizing Healthcare: The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Clinical Practice. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiotsa, B.; Naccache, B.; Duval, M.; Rocher, B.; Grall-Bronnec, M. Social Media Use and Body Image Disorders: Association between Frequency of Comparing One’s Own Physical Appearance to That of People Being Followed on Social Media and Body Dissatisfaction and Drive for Thinness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahramani, A.; de Courten, M.; Prokofieva, M. The Potential of Social Media in Health Promotion beyond Creating Awareness: An Integrative Review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtz, B.E.; Kanthawala, S. #T1DLooksLikeMe: Exploring Self-Disclosure, Social Support, and Type 1 Diabetes on Instagram. Front. Commun. 2020, 5, 510278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.E.; Cooper, H.C.; Milton, B. The Lived Experiences of Young People (13–16 Years) with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and Their Parents—A Qualitative Phenomenological Study. Diabet. Med. 2013, 30, e17–e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povlsen, L.; Olsen, B.; Ladelund, S. Diabetes in Children and Adolescents from Ethnic Minorities: Barriers to Education, Treatment and Good Metabolic Control. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 50, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juarascio, A.S.; Forman, E.M.; Herbert, J.D. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Versus Cognitive Therapy for the Treatment of Comorbid Eating Pathology. Behav. Modif. 2010, 34, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, K.K.; Hilliard, M.; Piatt, G.; Ievers-Landis, C.E. Effective Strategies for Encouraging Behavior Change in People with Diabetes. Diabetes Manag. 2015, 5, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempler, N.F.; Laursen, D.H.; Glümer, C. Culturally Sensitive Diabetes Education Supporting Ethnic Minorities with Type 2 Diabetes. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, ckz186.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).