Assessing Postnatal Immunisation Services in a Low-Resource Setting: A Cross-Sectional Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting and Population

2.3. Sample and Sampling Techniques

2.4. Development of the Questionnaire

2.5. Data Collection Procedures

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Validity and Reliability Measures

2.8. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Practices of Postnatal Immunisation Services

3.3. Factor Analysis on Practices of Postnatal Immunisation Services

3.3.1. Communalities

3.3.2. Principal Component Analysis: Total Variance Explained

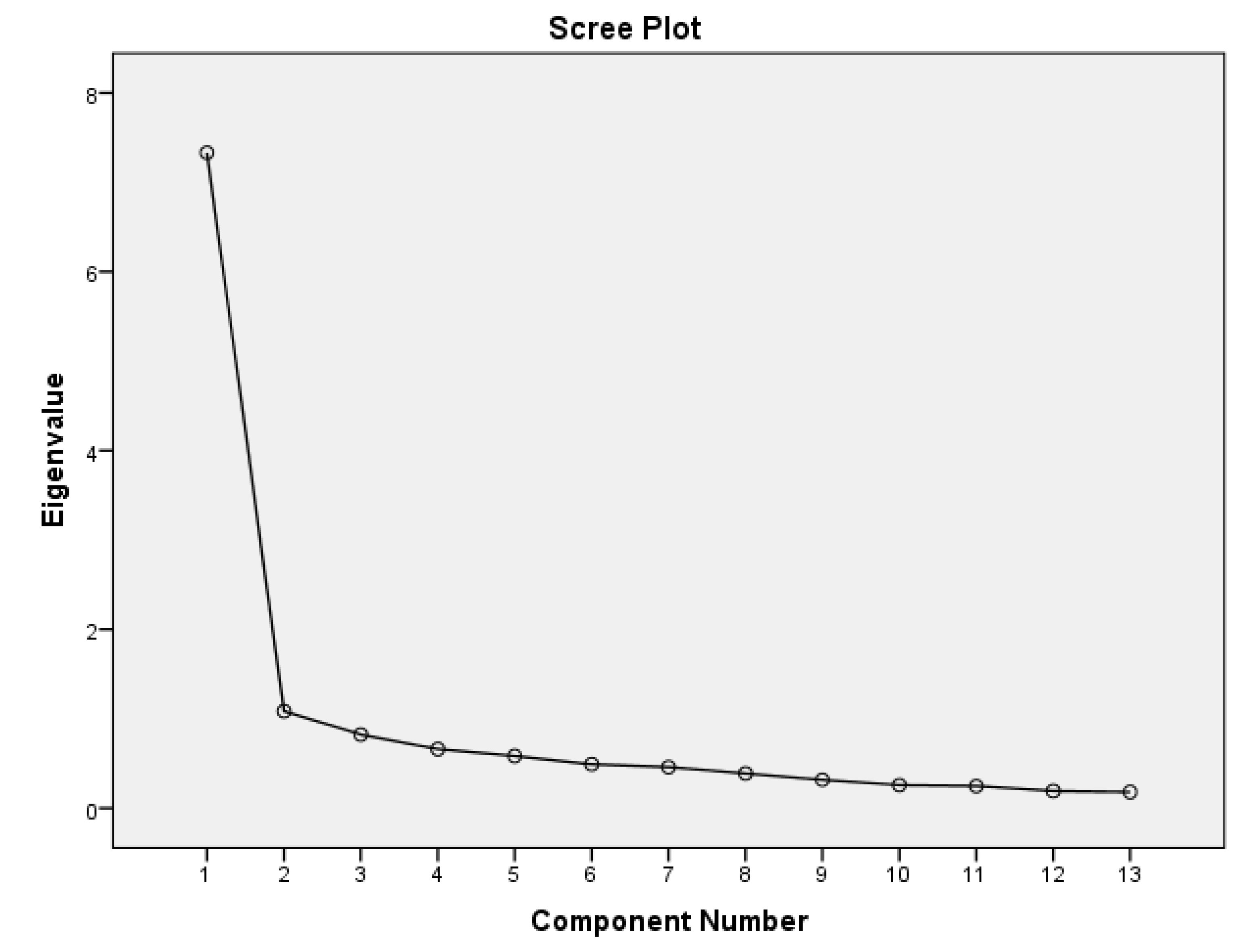

3.3.3. Scree Plot on Practices of Postnatal Immunisation

3.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis on Postnatal Immunisation Practices

3.4.1. Model Fits Indices

3.4.2. Factor Loadings and Significance on the Practices of Postnatal Immunisation

3.4.3. Reliability and Validity on the Practices of Postnatal Immunisation

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

4.3. Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EPI | Expanded Programme on Immunisation |

| BCG | Bacillus Calmette-Guérin |

| OPV | Oral polio vaccine |

| DPT | Diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus |

| PNC | Postnatal care |

| SEM | Socio-Ecological Model |

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| KMO | Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SRMR | Standardised Root Mean Square Residual |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

| IFI | Incremental Fit Index |

References

- Fleurant-Ceelen, A.; Tunis, M.; House, A. What is new in the Canadian Immunization Guide: November 2016 to November 2018. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2018, 44, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhalaria, P.; Kumar, P.; Kapur, S.; Singh, A.K.; Verma, A.K.; Agarwal, D.; Tripathi, B.; Taneja, G. Path to full immunisation coverage, role of each vaccine and their importance in the immunisation programme: A cross-sectional analytical study of India. BMJ Public Health 2025, 3, e001290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budu, E.; Darteh, E.K.M.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Seidu, A.-A.; Dickson, K.S. Trend and determinants of complete vaccination coverage among children aged 12–23 months in Ghana: Analysis of data from the 1998 to 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Surveys. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budu, E.; Seidu, A.-A.; Agbaglo, E.; Armah-Ansah, E.K.; Dickson, K.S.; Hormenu, T.; Hagan, J.E.; Adu, C.; Ahinkorah, B.O. Maternal healthcare utilization and full immunization coverage among 12–23 months children in Benin: A cross sectional study using population-based data. Arch. Public Health 2021, 79, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konje, E.T.; Hatfield, J.; Sauve, R.; Kuhn, S.; Magoma, M.; Dewey, D. Late initiation and low utilization of postnatal care services among women in the rural setting in Northwest Tanzania: A community-based study using a mixed method approach. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Ghana 2020 Annual Report; WHO Regional Office for Africa: Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo, 2021; Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/who-ghana-2020-annual-report (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Danso, S.E.; Frimpong, A.; Seneadza, N.A.H.; Ofori, M.F. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of caregivers on childhood immunization in Okaikoi sub-metro of Accra, Ghana. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1230492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donfouet, H.P.P.; Agesa, G.; Mutua, M.K. Trends of inequalities in childhood immunization coverage among children aged 12–23 months in Kenya, Ghana, and Côte d’Ivoire. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintyamena, U.; Azizatunnisa’, L.; Ahmad, R.A.; Mahendradhata, Y. Scaling up public health interventions: Case study of the polio immunization program in Indonesia. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanpaabadai, E.A.; Adiak, A.A.; Nukpezah, R.N.; Adokiya, M.N.; Adjei, S.E.; Boah, M. Population-based cross-sectional study of factors influencing full vaccination status of children aged 12–23 months in a rural district of the Upper East Region, Ghana. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, A.; Issaka, J.; Ayebeng, C.; Okyere, J. Influence of women empowerment on childhood (12–23 months) immunization coverage: Recent evidence from 17 sub-Saharan African countries. Trop. Med. Health 2023, 51, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, B.; Aborigo, R.A.; Dalaba, M.; Opare, J.K.L.; Conklin, L.; Bonsu, G.; Amponsa-Achiano, K. Community Barriers, Enablers, and Normative Embedding of Second Year of Life Vaccination in Ghana: A Qualitative Study. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2023, 11, e2200496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeboah, D.; Owusu-Marfo, J.; Agyeman, Y.N. Predictors of malaria vaccine uptake among children 6–24 months in the Kassena Nankana Municipality in the Upper East Region of Ghana. Malar. J. 2022, 21, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, K.; Joga, A.; Dutse, U.; Hasan, K.; Aziz, A.; Ansari, U.; Gidado, Y.; Baba, M.C.; Gamawa, A.I.; Mohammad, R.; et al. Impact of universal home visits on child health in Bauchi State, Nigeria: A stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girma Tareke, K.; Feyissa, G.T.; Kebede, Y. Exploration of barriers to postnatal care service utilization in Debre Libanos District, Ethiopia: A descriptive qualitative study. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2022, 3, 986662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yawson, A.E.; Bonsu, G.; Senaya, L.K.; Yawson, A.O.; Eleeza, J.B.; Awoonor-Williams, J.K.; Banskota, H.K.; Agongo, E.E.A. Regional disparities in immunization services in Ghana through a bottleneck analysis approach: Implications for sustaining national gains in immunization. Arch. Public Health 2017, 75, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, K.; Pacheco, G.; Plum, A. State dependence in immunization and the role of discouragement. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2023, 51, 101313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caperon, L.; Saville, F.; Ahern, S. Developing a socio-ecological model for community engagement in a health programme in an underserved urban area. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogardus, R.L.; Martin, R.J.; Richman, A.R.; Kulas, A.S. Applying the Socio-Ecological Model to barriers to implementation of ACL injury prevention programs: A systematic review. J. Sport Health Sci. 2019, 8, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J. Cross-Sectional Survey Design. In SAGE Research Methods; Sage Publishing: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, A.M. Sample Size Determination in Survey Research. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2020, 26, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Lela, O.Q.B.; Bahari, M.B.; Al-Abbassi, M.G.; Basher, A.Y. Development of a questionnaire on knowledge, attitude and practice about immunization among Iraqi parents. J. Public Health 2011, 19, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadh, A.I.; Hassali, M.A.; Al-Lela, O.Q.; Bux, S.H.; Elkalmi, R.M.; Hadi, H. Immunization knowledge and practice among Malaysian parents: A questionnaire development and pilot-testing. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasundaram, N. Factor Analysis: Nature, Mechanism and Uses in Social and Management Science Research. J. Cost Manag. Account. 2009, 37, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Goretzko, D.; Siemund, K.; Sterner, P. Evaluating Model Fit of Measurement Models in Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2024, 84, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sürücü, L.; Maslakçi, A. Validity and Reliability in Quantitative Research. Bus. Manag. Stud. Int. J. 2020, 8, 2694–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetene, S.M.; Negash, W.D.; Shewarega, E.S.; Asmamaw, D.B.; Belay, D.G.; Teklu, R.E.; Aragaw, F.M.; Alemu, T.G.; Eshetu, H.B.; Fentie, E.A. Determinants of full immunization coverage among children 12–23 months of age from deviant mothers/caregivers in Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis using 2016 demographic and health survey. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1085279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelagay, A.A.; Worku, A.G.; Bashah, D.T.; Tebeje, N.B.; Gebrie, M.H.; Yeshita, H.Y.; Cherkose, E.A.; Ayana, B.A.; Lakew, A.M.; Bitew, D.A.; et al. Complete childhood vaccination and associated factors among children aged 12–23 months in Dabat demographic and health survey site, Ethiopia, 2022. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asefa, A.; Getachew, B.; Belete, A.M.; Molla, D. Knowledge and Practice on Birth Preparedness, Complication Readiness among Pregnant Women Visiting Debreberhan Town Governmental Health Institutions, North-East Ethiopia. J. Women’s Health Care 2022, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bangura, J.B.; Xiao, S.; Qiu, D.; Ouyang, F.; Chen, L. Barriers to childhood immunization in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibraheem, R.; Akintola, M.; Abdulkadir, M.; Ameen, H.; Bolarinwa, O.; Adeboye, M. Effects of call reminders, short message services (SMS) reminders, and SMS immunization facts on childhood routine vaccination timing and completion in Ilorin, Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 2021, 21, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosef, T.; Getachew, D.; Weldekidan, F. Health professionals’ knowledge and practice of essential newborn care at public health facilities in Bench-Sheko Zone, southwest Ethiopia. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiano, G.; Nardi, A. Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19. Public Health 2021, 194, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuwarda, R.F.; Ramzan, I.; Weekes, L.; Kayser, V. Vaccine Hesitancy: Contemporary Issues and Historical Background. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attwell, K.; Dube, E.; Gagneur, A.; Omer, S.B.; Suggs, L.S.; Thomson, A. Vaccine Acceptance: Science, Policy, and Practice in a ‘Post-Fact’ World. Vaccine 2019, 37, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omomila, J.; Ogunyemi, A.; Kanma-Okafor, O.; Ogunnowo, B. Vaccine-related knowledge and utilization of childhood immunization among mothers in urban Lagos. Niger. J. Paediatr. 2020, 47, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Freq. | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 18–22 | 18 | 9.8 |

| 23–26 | 41 | 22.3 | |

| 27–30 | 56 | 30.4 | |

| 31–34 | 29 | 15.8 | |

| 35–38 | 25 | 13.6 | |

| 39–42 | 12 | 6.5 | |

| Above 42 | 3 | 1.6 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 54 | 29.3 |

| Married | 87 | 47.3 | |

| Consensual Union | 7 | 3.8 | |

| Never married | 3 | 1.7 | |

| Divorced | 33 | 17.9 | |

| Religion | Christian | 142 | 77.2 |

| Islam | 42 | 22.8 | |

| Number of Children | 1 | 60 | 32.6 |

| 2 | 65 | 35.3 | |

| 3 | 38 | 20.7 | |

| 4 | 18 | 9.8 | |

| 5 | 3 | 1.6 | |

| Occupational Status | Employed (full-time) | 60 | 32.6 |

| Employed (part-time) | 29 | 15.7 | |

| Self-employed | 68 | 37.0 | |

| Unemployed | 27 | 14.7 | |

| Education attainment | No education | 14 | 7.6 |

| Basic education | 15 | 8.2 | |

| Secondary education | 45 | 24.5 | |

| Tertiary education | 76 | 41.2 | |

| Postgraduate | 11 | 6.0 | |

| Vocational | 23 | 12.5 | |

| Partner’s level of education | No education | 7 | 3.8 |

| Basic education | 7 | 3.8 | |

| Secondary education | 29 | 15.8 | |

| Tertiary education | 102 | 55.4 | |

| Postgraduate | 25 | 13.6 | |

| Vocational | 14 | 7.6 | |

| Residence | Urban | 106 | 57.6 |

| Peri-Urban | 35 | 19.0 | |

| Rural | 43 | 23.4 | |

| Distance from your home to the postnatal clinic | Below 30 min | 33 | 17.9 |

| About 30 min to one hour | 70 | 38.1 | |

| Above one hour | 81 | 44.0 | |

| Mode of transportation | On foot | 27 | 14.7 |

| By car | 157 | 85.3 | |

| Gender of the infant | Male | 73 | 39.7 |

| Female | 111 | 60.3 | |

| Pregnancy status | Planned | 116 | 63.1 |

| Unplanned | 58 | 31.5 | |

| Unmet needs | 10 | 5.4 | |

| Place of delivery | Home | 8 | 4.3 |

| Health facilities | 168 | 91.3 | |

| TBA | 8 | 4.4 | |

| Number of PNC visits | One time | 27 | 14.7 |

| Two time | 84 | 45.7 | |

| More than two times | 73 | 39.6 | |

| The last vaccine the infant received | At birth | 18 | 9.8 |

| Six weeks | 75 | 40.8 | |

| Ten weeks | 27 | 14.7 | |

| Fourteen weeks | 53 | 28.7 | |

| Not sure | 11 | 6.0 | |

| Mother’s tetanus-diphtheria | No dose received | 7 | 3.8 |

| 1 dose received | 42 | 22.8 | |

| 2 doses received | 77 | 41.8 | |

| 3 doses received | 58 | 31.6 |

| Statements | Mean | Mode | Std. Deviation | Percentiles | IQR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 50 | 75 | |||||

| I adhere to the recommended vaccine schedule provided by the healthcare professional in ensuring that my infant receive vaccination at the appropriate times. | 3.857 | 4 | 1.075 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 1 |

| I am satisfied with the communication methods used to remind me on fellow ups for postnatal immunisation appointments | 3.698 | 4 | 1.139 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| I am offered comprehensive resource on postnatal immunisation education and vaccine preventable diseases | 3.788 | 4 | 1.009 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| I understand the importance of postnatal immunisation for the health and well-being of my infant. | 3.757 | 4 | 1.098 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Postnatal immunisation services adequately address my cultural and linguistic needs. | 3.778 | 4 | 0.907 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| I feel satisfied with the level of comfort and privacy provided during postnatal immunisation sessions for me and my infant. | 3.439 | 4 | 1.107 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| I am satisfied with the professionalism and expertise demonstrated by healthcare providers delivering postnatal immunisation services. | 3.497 | 4 | 1.079 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Postnatal immunisation services offer me adequate information on potential vaccine side effects and how to manage them | 3.672 | 4 | 0.967 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| The location and hours of operation is convenient for my infant’s postnatal immunisation services. | 2.735 | 2 | 1.417 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| I maintain records of my infant’s postnatal immunisations including the types of vaccines received and the date administered in the vaccination booklets provided by the hospital. | 3.825 | 4 | 0.835 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| I receive adequate support and guidance for managing any adverse reactions or side effects. | 3.513 | 4 | 1.019 | 2.5 | 4 | 4 | 1.5 |

| I seek information and support from healthcare providers at the hospital regarding postnatal immunisations including questions or concerns about the immunisation process or vaccine safety. | 3.508 | 4 | 1.109 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| I recommend postnatal immunisation services to other parents/caregivers based on my experience. | 3.926 | 4 | 0.919 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 1 |

| Statement: Good Postnatal Immunisation Practices | Initial | Extraction |

|---|---|---|

| I am satisfied with the communication methods used to remind me on fellow ups for postnatal immunisation appointments | 1.000 | 0.718 |

| I understand the importance of postnatal immunisation for the health and well-being of my infant. | 1.000 | 0.746 |

| I feel satisfied with the level of comfort and privacy provided during postnatal immunisation sessions for me and my infant. | 1.000 | 0.756 |

| I am satisfied with the professionalism and expertise demonstrated by healthcare providers delivering postnatal immunisation services. | 1.000 | 0.706 |

| Statement: Inadequate Postnatal Immunisation Practices | Initial | Extraction |

| I adhere to the recommended vaccine schedule provided by the healthcare professional in ensuring that my infant receive vaccination at the appropriate times. | 1.000 | 0.668 |

| I am offered comprehensive resource on postnatal immunisation education and vaccine preventable diseases | 1.000 | 0.682 |

| Postnatal immunisation services adequately address my cultural and linguistic needs. | 1.000 | 0.529 |

| Postnatal immunisation services offer me adequate information on potential vaccine side effects and how to manage them. | 1.000 | 0.647 |

| The location and hours of operation is convenient for my infant’s postnatal immunisation services. | 1.000 | 0.625 |

| I maintain records of my infant’s postnatal immunisations including the types of vaccines received and the date administered in the vaccination booklets provided by the hospital. | 1.000 | 0.536 |

| I receive adequate support and guidance for managing any adverse reactions or side effects. | 1.000 | 0.647 |

| I seek information and support from healthcare providers at the hospital regarding postnatal immunisations including questions or concerns about the immunisation process or vaccine safety. | 1.000 | 0.655 |

| I recommend postnatal immunisation services to other parents/caregivers based on my experience. | 1.000 | 0.503 |

| Component | Initial Eigenvalues | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % of Variance | Cumulative% | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative% | |

| Adherence to schedule | 7.333 | 56.407 | 56.407 | 7.333 | 56.407 | 56.407 |

| Satisfaction with postnatal immunisation communication | 1.084 | 8.338 | 64.745 | 1.084 | 8.338 | 64.745 |

| Offered comprehensive resources. | 0.822 | 6.324 | 71.069 | |||

| Understand the importance of immunisation | 0.659 | 5.068 | 76.137 | |||

| Immunisation adequately addresses my culture and linguistic needs | 0.582 | 4.480 | 80.617 | |||

| Satisfaction with level of comfort and privacy | 0.490 | 3.770 | 84.387 | |||

| Satisfaction with professionalism | 0.459 | 3.530 | 87.916 | |||

| Immunisation services offer me adequate information | 0.387 | 2.980 | 90.897 | |||

| Convenient location and hours of operation | 0.315 | 2.423 | 93.320 | |||

| Maintain immunisation records of my infant | 0.256 | 1.973 | 95.293 | |||

| Receive adequate support and guidance | 0.244 | 1.878 | 97.171 | |||

| Seek information and support from healthcare providers | 0.190 | 1.461 | 98.632 | |||

| Recommendation of postnatal immunisation services | 0.178 | 1.368 | 100.000 | |||

| 95% Confidence Interval | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Indicator | Estimate | Std. Error | z-Value | p | Lower | Upper |

| Immunisation Adherence | Comprehensive resources | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Recommend postnatal immunisation | 0.683 | 0.075 | 9.114 | <0.001 | 0.536 | 0.830 | |

| Cultural needs | 0.706 | 0.073 | 9.652 | <0.001 | 0.562 | 0.849 | |

| Information on Vaccine effects | 0.913 | 0.073 | 12.509 | <0.001 | 0.770 | 1.056 | |

| Seeking information on immunisation | 1.054 | 0.083 | 12.622 | <0.001 | 0.890 | 1.217 | |

| Adherence to immunisation | 0.912 | 0.084 | 10.808 | <0.001 | 0.747 | 1.078 | |

| Effective communication | Comfort and privacy | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Professionalism and expertise | 0.938 | 0.072 | 13.012 | <0.001 | 0.796 | 1.079 | |

| Convenient location | 0.867 | 0.105 | 8.231 | <0.001 | 0.660 | 1.073 | |

| Adequate support and guidance | 0.859 | 0.069 | 12.488 | <0.001 | 0.724 | 0.994 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abukari, A.S.; Gaddah, R.; Ayivor, E.V.; Haruna, I.S.; Korsah, E.K. Assessing Postnatal Immunisation Services in a Low-Resource Setting: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121389

Abukari AS, Gaddah R, Ayivor EV, Haruna IS, Korsah EK. Assessing Postnatal Immunisation Services in a Low-Resource Setting: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Healthcare. 2025; 13(12):1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121389

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbukari, Alhassan Sibdow, Rejoice Gaddah, Emmanuella Vincentia Ayivor, Ibrahim Sadik Haruna, and Emmanuel Kwame Korsah. 2025. "Assessing Postnatal Immunisation Services in a Low-Resource Setting: A Cross-Sectional Survey" Healthcare 13, no. 12: 1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121389

APA StyleAbukari, A. S., Gaddah, R., Ayivor, E. V., Haruna, I. S., & Korsah, E. K. (2025). Assessing Postnatal Immunisation Services in a Low-Resource Setting: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Healthcare, 13(12), 1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121389