The Impact of Mindfulness Programmes on Anxiety, Depression and Stress During Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- Implement a mindfulness (MF) intervention during pregnancy;

- Measure its effects on anxiety, depression, or stress post-intervention.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Selection of Studies for Analysis

2.4. Data Extraction and Formulation

2.5. Risk of Bias and Level of Evidence

2.6. Effect Measures and Data Synthesis

3. Results

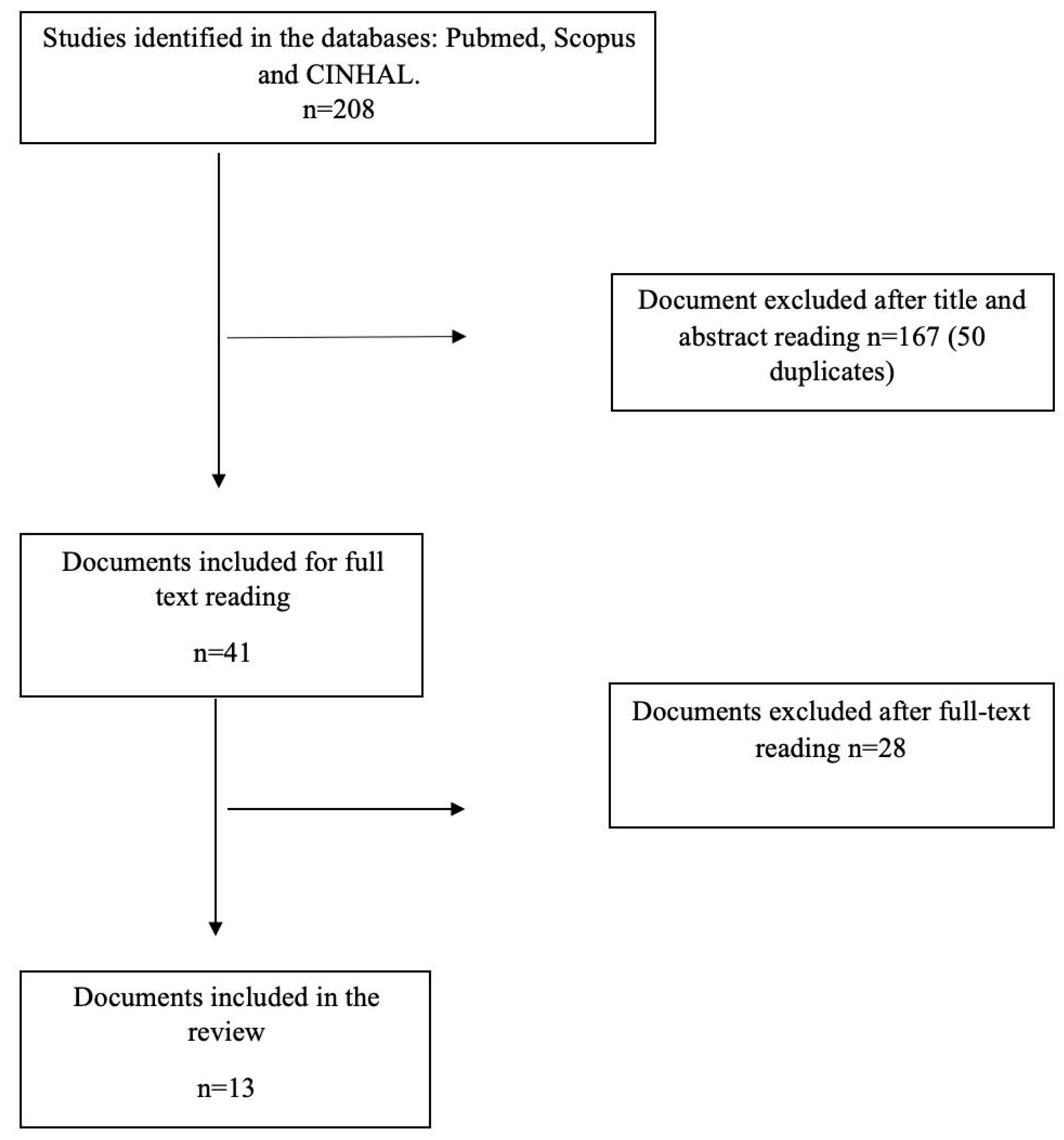

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Characteristics of the Studies Included

3.3. Results of MF in Anxiety, Stress, and Depression

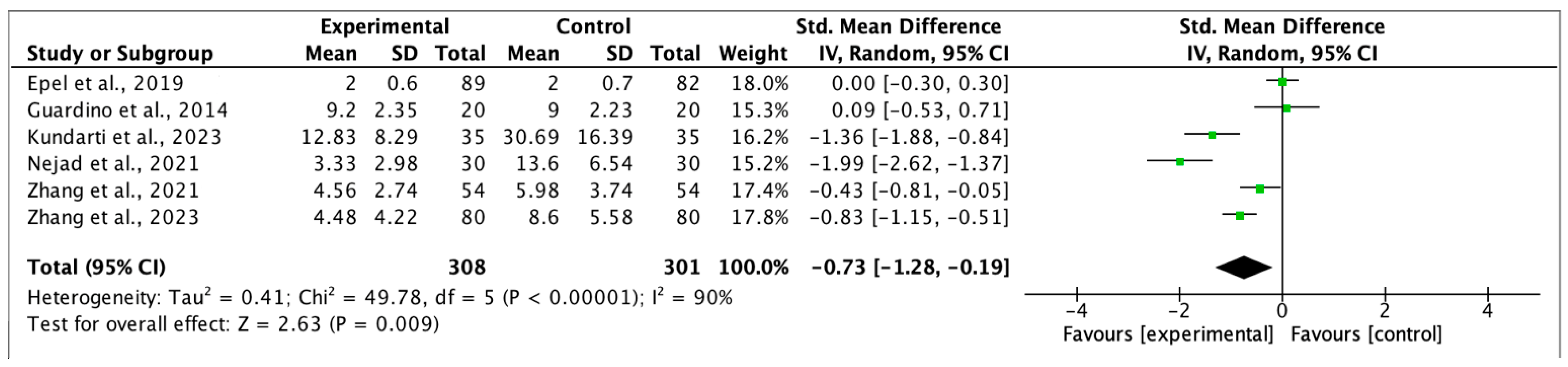

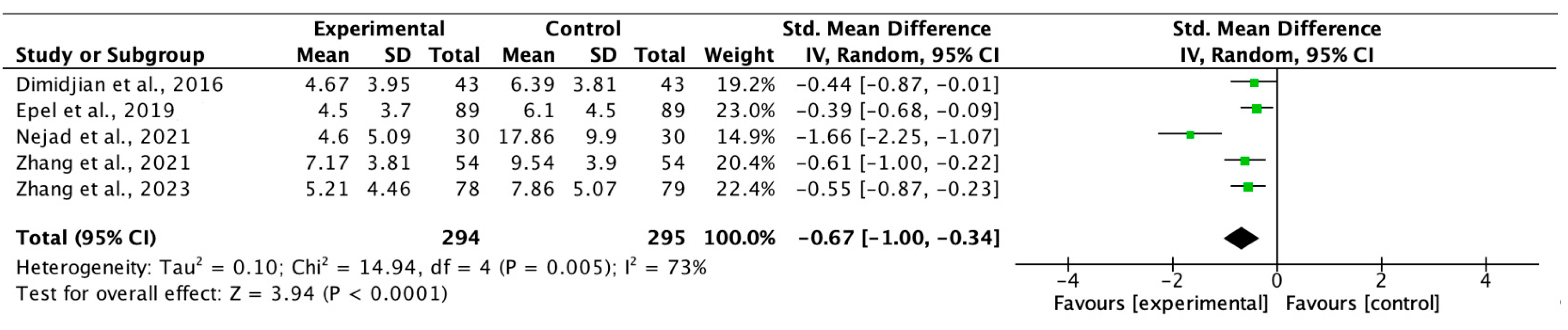

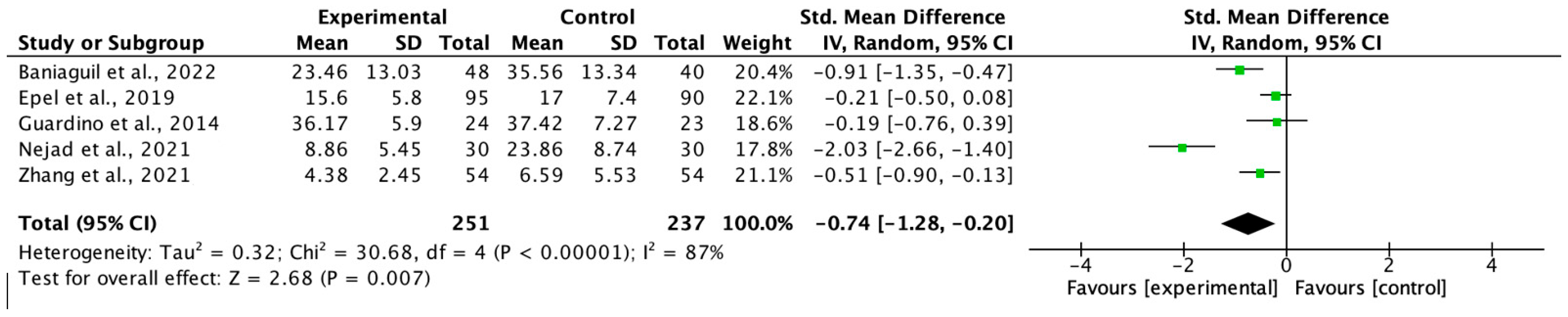

3.4. Results of the Meta-Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abatemarco et al., 2021 [29] Agampodi et al., 2019 [30] | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes |

| Agampodi et al., 2019 [30] | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes |

| Baniaghil et al., 2022 [31] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dimidjiam et al., 2016 [32] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Epel et al., 2019 [33] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Goodman et al., 2014 [34] | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Guardinoa et al., 2014 [35] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes |

| Kalmbach et al., 2023 [36] | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes |

| Kumdarti et al., 2023 [37] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes |

| Nejad et al., 2021 [38] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes |

| Pan et al., 2023 [39] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Zhang et al., 2023 [40] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Zhang et al., 2021 [41] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

References

- González Merlo, J.; Laílla Vicens, J.M.; Fabre González, E.; González Bosquet, E. Obstetricia, 6th ed.; Elsevier: Barcelona/Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez López, E.; Aldana Calva, E.; Carreño Meléndez, J.; Sánchez Bravo, C. Alteraciones Psicológicas en la Mujer Embarazada. Psicol. Iberoam. 2006, 14, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Răchită, A.; Strete, G.E.; Suciu, L.M.; Ghiga, D.V.; Sălcudean, A.; Mărginean, C. Psychological Stress Perceived by Pregnant Women in the Last Trimester of Pregnancy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, G.M.; Correia, J.M.; Esparza, P.; Saxena, S.; Maj, M. The WPA-WHO Global Survey of Psychiatrists’ Attitudes Towards Mental Disorders Classification. World Psychiatry 2011, 10, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Stubbs, B.; Koyanagi, A.; Dragioti, E.; Jacob, L.; Carvalho, A.F.; Radua, J.; et al. Environmental risk factors, protective factors, and biomarkers for postpartum depressive symptoms: An umbrella review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 140, 104761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauskopf, V.; Valenzuela, P. Depresión perinatal: Detección, diagnóstico y estrategias de tratamiento. Rev. Médica Clínica Las Condes 2020, 31, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). Depresión. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/health-topics/depression#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Del Moral, A.O.; Romero, A.M.R.; Iglesias, Y.G. [Postpartum depression: Suspicion criteria, diagnosis and treatment]. FMC Form. Médica Contin. En Atención Primaria 2020, 27, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5: Manual de Diagnóstico Diferencial; Editorial Médica Panamericana S.A.: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, M.; Amato, R.; Chávez, J.G.; Ramirez, M.; Rangel, S.; Rivera, L.; López, J. Depresión y ansiedad en embarazadas. Salus 2013, 17, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, H.; Hidaka, N.; Kawagoe, C.; Odagiri, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Ikeda, T.; Ishizuka, Y.; Hashiguchi, H.; Takeda, R.; Nishimori, T.; et al. Prenatal psychological stress causes higher emotionality, depression-like behavior, and elevated activity in the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Neurosci. Res. 2007, 59, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Health Data Exchange. Seattle: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. 2019. Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results?params=gbd-api-2019-permalink/716f37e05d94046d6a06c1194a8eb0c9 (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Dunkel Schetter, C.; Rahal, D.; Ponting, C.; Julian, M.; Ramos, I.; Hobel, C.J.; Coussons-Read, M. Anxiety in pregnancy and length of gestation: Findings from a large population-based study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184356. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36154104/doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0184356 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Huizink, A.C.; Mulder, E.J.H.; Robles de Medina, P.G.; Visser, G.H.A.; Buitelaar, J.K. Is pregnancy anxiety a distinctive syndrome? Early Hum. Dev. 2004, 79, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Stress at the Workplace; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/stress (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Wedel, H.K. Depresion, ansiedad y disfuncion familiar en el embarazo. Rev. Médica Sinerg. 2018, 3, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Paredes, J.F.; Jácome-Pérez, N. Depresión en el embarazo. Rev. Colomb. De Psiquiatria 2019, 48, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonari, L.; Pinto, N.; Ahn, E.; Einarson, A.; Steiner, M.; Koren, G. Perinatal risks of untreated depression during pregnancy. Can. J. Psychiatry 2004, 49, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bergh, B.R.; Mulder, E.J.; Mennes, M.; Glover, V. Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioural development of the fetus and child: Links and possible mechanisms. A review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005, 29, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, S.H.; Lam, R.W.; Parikh, S.V.; Patten, S.B.; Ravindran, A.V. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of majordepressive disorder in adults. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 117, S1–S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schetter, C.D.; Tanner, L. Anxiety, depression and stressin pregnancy. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2012, 25, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Coming to Our Senses: Healing Ourselves and the World Through Mindfulness; Hachette: London, UK, 2005; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Sanchez, L.; Garcia-Banda, G.; Servera, M.; Verd, S.; Filgueira, A.; Cardo, E. Benefits of mindfulness in pregnant women. Medicina 2020, 80, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Woolhouse, H.; Mercuri, K.; Judd, F.; Brown, S.J. Antenatalmindfulness intervention to reduce depression, anxiety and stress: A pilot randomised controlled trial of theMindBabyBody program in an Australian tertiary maternityhospital. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T. Prenatal depression effects on early development: A review. Infant Behav. Dev. 2011, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepes-Nuñez, J.J.; Urrútia, G.; Romero-García, M.; Alonso-Fernández, S. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM). Levels of Evidence. 2009. Available online: http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=1025 (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatemarco, D.J.; Gannon, M.; Short, V.L.; Baxter, J.; Metzker, K.M.; Reid, L.; Catov, J.M. Mindfulness in Pregnancy: A Brief Intervention for Women at Risk. Matern. Child Health J. 2021, 25, 1875–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agampodi, T.; Katumuluwa, S.; Pattiyakumbura, T.; Rankaduwa, N.; Dissanayaka, T.; Agampodi, S. Feasibility of incorporating mindfulness based mental health promotion to the pregnancy care program in Sri Lanka: A pilot study. F1000Research 2019, 7, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baniaghil, A.S.; Ebrahimi, F.; Aghili, S.M.; Behnampour, N.; Moghasemi, S. The effectiveness of group counseling based on mindfulness on pregnancy worries and stress in Nulligravida women: A randomized field trial. J. Nurs. Midwifery Sci. 2022, 9, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimidjian, S.; Goodman, S.H.; Felder, J.N.; Gallop, R.; Brown, A.P.; Beck, A. Staying well during pregnancy and the postpartum: A pilot randomized trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for the prevention of depressive relapse/recurrence. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 84, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epel, E.; Laraia, B.; Coleman-Phox, K.; Leung, C.; Vieten, C.; Mellin, L.; Kristeller, J.L.; Thomas, M.; Stotland, N.; Bush, N.; et al. Effects of a Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Distress, Weight Gain, and Glucose Control for Pregnant Low-Income Women: A Quasi-Experimental Trial Using the ORBIT Model. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2019, 26, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, J.H.; Guarino, A.; Chenausky, K.; Klein, L.; Prager, J.; Petersen, R.; Forget, A.; Freeman, M. CALM Pregnancy: Results of a pilot study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for perinatal anxiety. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2014, 17, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardino, C.M.; Schetter, C.D.; Bower, J.E.; Lu, M.C.; Smalley, S.L. Randomised controlled pilot trial of mindfulness training for stress reduction during pregnancy. Psychol. Health 2014, 29, 334–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmbach, D.A.; Cheng, P.; Reffi, A.N.; Ong, J.C.; Swanson, L.M.; Fresco, D.M.; Walch, O.; Seymour, G.M.; Fellman-Couture, C.; Bayoneto, A.D.; et al. Perinatal Understanding of Mindful Awareness for Sleep (PUMAS): A single-arm proof-of-concept clinical trial of a mindfulness-based intervention for DSM-5 insomnia disorder during pregnancy. Sleep Med. 2023, 108, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundarti, F.I.; Komalyna, I.N.T.; Titisari, I.; Kiswati, K.; Jamhariyah, J. Kiswati Assessing the Effects of Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Anxiety and Cortisol in Pregnancy. Univers. J. Public Health 2023, 11, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, F.K.; Shahraki, K.A.; Nejad, P.S.; Moghaddam, N.K.; Jahani, Y.; Divsalar, P. The influence of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on stress, anxiety and depression due to unwanted pregnancy: A randomized clinical trial. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2021, 62, E82–E88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, W.-L.; Lin, L.-C.; Kuo, L.-Y.; Chiu, M.-J.; Ling, P.-Y. Effects of a prenatal mindfulness program on longitudinal changes in stress, anxiety, depression, and mother–infant bonding of women with a tendency to perinatal mood and anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Mao, F.; Wu, L.; Huang, Y.; Sun, J.; Cao, F. Effectiveness of Digital Guided Self-help Mindfulness Training During Pregnancy on Maternal Psychological Distress and Infant Neuropsychological Development: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e41298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, P.; Sun, J.; Sun, Y.; Shao, D.; Cao, D.; Cao, F. Prenatal stress self-help mindfulness intervention via social media: A randomized controlled trial. J. Ment. Health 2021, 32, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbar, S.M.; Oyarzabal, A.J.B.; Oyarzabal, E.A. Meditation and Mindfulness in Pregnancy and Postpartum: A Review of the Evidence. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 64, 661–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhillon, A.; Sparkes, E.; Duarte, R.V. Mindfulness-Based Interventions During Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 1421–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Li, H.; Wang, D.; Shan, L.; Wang, F.; Kang, Y. Efficacy of nondrug interventions in perinatal depression: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 317, 114916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, W.-L.; Chang, C.-W.; Chen, S.-M.; Gau, M.-L. Assessing the effectiveness of mindfulness-based programs on mental health during pregnancy and early motherhood—A randomized control trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, B.; Wang, T.; Wu, Z.; Huang, X.; Li, S. Effect of mindfulness meditation on depression during pregnancy: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 963133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Martín, M.D.; Guillén-Gallego, I. Efectividad del uso del mindfulness durante el embarazo, el parto y el posparto. Matronas Prof. 2020, 21–22, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Aktürk, S.O.; Yılmaz, T. Mindfulness in Pregnancy, Childbirth and Parenting. Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Hemşirelik Fakültesi Elektron. Derg. 2023, 16, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, H.S.; Urizar, G.G.; Yim, I.S. The influence of mindfulness and social support on stress reactivity during pregnancy. Stress Health 2019, 35, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isgut, M.; Smith, A.K.; Reimann, E.S.; Kucuk, O.; Ryan, J. The impact of psychological distress during pregnancy on the developing fetus: Biological mechanisms and the potential benefits of mindfulness interventions. J. Perinat. Med. 2017, 45, 999–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansen, S.L.; Robakis, T.K.; Williams, K.E.; Rasgon, N.L. Management of perinatal depression with non-drug interventions. BMJ 2019, 364, l322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization WHO. Recommendations: Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550215 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Feli, R.; Heydarpour, S.; Yazdanbakhsh, K.; Heydarpour, F. The effect of mindfulness-based counselling on the anxiety levels and childbirth satisfaction among primiparous pregnant women: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökbulut, N.; Cengizhan, S.Ö.; Akça, E.I.; Ceran, E. The effects of a mindfulness-based stress reduction program and deep relaxation exercises on pregnancy-related anxiety levels: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2024, 30, e13238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s); Year and Country of Publication; [Paper No.] | Study Design | Sample Size and Mean Age of Participants | Description of MF Intervention | Anxiety | Depression | Stress | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) Pre- | Mean (SD) Post- | Mean (SD) Pre- | Mean (SD) Post- | Mean (SD) Pre- | Mean (SD) Post- | ||||

| Abatemarco et al., 2021 USA [29] | Experimental study MF-based intervention for pregnant women at high risk for preterm birth, considering stress, anxiety, and depression, together with race (African American) and low socioeconomic status. | Sample: n = 35 Age 18–24 years: n = 7 (20.0%) Age 25–35 years; n = 24 (68.6%) Age ≥ 36 years: n = 4 (11.4%) Completed first part of the study (Post 1) n = 27 (77%) Completed seven months postpartum (Post 2) n = 19 (54%) | Six two-hour sessions (once weekly) during pregnancy, focusing on stress, anxiety, MF, and depression. Study variables evaluated 2 months post-intervention and during the postpartum period (7 months post-intervention). Questionnaires used to evaluate the study variables:

| Baseline n = 35 13.0 (0.53) | POST 1 n = 27 11.2 (0.57) POST 2 n = 19 10.2 (0.74) | Baseline n = 35 11.3 (0.98) | POST 1 n = 27 1.4 (1.16) POST 2 n = 19 8.2 (1.2) | Baseline n = 35 20.7 (1.0) | POST 1 n = 27 16.5 (1.2) POST 2 n = 19 15.7 (1.3) |

| Agampodi et al., 2019 Sri Lanka [30] | Experimental study Incorporating an MF-based programme into prenatal care. | Sample size predetermined, not calculated n = 12–15 Final sample size: n = 12 Age: 18–30 years Characteristics of participants

| Eight sessions, of 2–3 h, once weekly. Semi-structured, anonymous, self-administered questionnaires were used to determine the cultural appropriateness, utility and feasibility of the programme. Overall goal: to promote mental well-being. | --- | --- | --- | --- | n = 12 All participants reported a change in how they responded to stressful situations, such as household and work tasks. Moreover, they worked more efficiently, achieving greater comfort and relaxation, in body and mind. | 7 of the 8 women observed reduced stressors in their daily lives and gained a sense of calm. 3 of the 8 women felt they were better able to control their anger. |

| Baniaghil et al., 2022 Iran [31] | Randomised field study To determine the effect of MF-based group counselling on worries and stress for women during a first pregnancy. | 114 women, never previously pregnant. Divided into two groups: Intervention group (n = 53) Age (mean ± SE) 26.21 ± 4.61 years Control group (n = 61) Age (mean ± SE) 25.52 ± 4.38 years Gestational age 12–20 weeks | For the intervention group, eight weekly sessions of 120–150 min) Data were compiled and groups formed using the Pregnancy Worries and Stress Questionnaire PSWQ Each intervention group completed the PWSQ at the end of the eighth session. Simultaneously, the control groups were asked over the phone to complete the questionnaire again on the same day or the day after the intervention groups’ last session. Based on the available data, all 96 participants in both the intervention and control groups completed the questionnaire upon con-clusion of the final session. | --- | --- | --- | --- | 23.46 (13.03) | 34.96 (15.88) Mean pregnancy stress and worry scores before and after MF-based group counselling improved by 11 units. |

| Dimidjian et al., 2016 USA [32] | Randomised clinical trial Applying MF-based cognitive therapy versus usual care to prevent the recurrence of perinatal depression. | 86 pregnant women with a history of depression. Divided into two groups: Intervention group: 43 women underwent MF-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) for Perinatal Depression Age: 30.98 (SE: 4.08) years 26 women completed the intervention Control group: 43 women received usual treatment (UT) 36 women completed the intervention Age: 28.72 (SE: 5.50) years | 8 sessions, of which 7 were practical. Each 6-day week was considered a session. Total duration: 42 days. To consider the intervention completed, at least 4 sessions must be attended. The first session consisted of an SCID-I/P interview (diagnosis and statistics of mental disorders) and a DSM-IV interview (to evaluate the presence of personality disorders). The possible recurrence of depression was assessed by Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation, a semi-structured interview, consistent with DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria at 8 weeks and 1 month prepartum and 1 and 6 months postpartum, to assess recurrence status after the intervention. The Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS) was used to assess the severity of depression symptoms. This evaluation was performed at baseline, immediately before randomisation, midway through, and immediately following the intervention, at each session of MBCT-PD, and monthly for the remainder of pregnancy and up to six months postpartum 8-item self-reported Client Satisfaction Questionnaire completed at the 8-week and 6-month postpartum assessments. | --- | --- | First, the power of the statistical test comparing MBCT-PD and UT was calculated. For this population sample (n = 86), the dropout rate was 19.8% during follow-up, the statistical power obtained was 71.4% and 81.4% for the two- and one-tailed tests, respectively For a 30% difference in the relapse rate, the statistical power was 84.3%. | MF group Relapses at 6 months: 18.4% Control group Relapses at 6 months: 50.2% For the MF group, the risk of relapse was 30% lower. According to CSQ-8, 90% of the MF participants were committed and highly satisfied. | --- | --- |

| Epel et al., 2019 USA [33] | Quasi-experimental study Stress can provoke excessive weight gain. Analysis of MF-based stress reduction (Mindful Moms Training, MMT). | n = 215 Divided into two groups: Control group (n = 105) Age (SD) = 28.0 (6.0) years Completed the intervention: n = 90 Intervention group (n = 110) Age (SD) = 27.8 (5.7) years Completed the intervention: n= 95 | 8 weekly sessions of 2 h of Mindful Moms Training (MMT) 2 booster telephone sessions, 1 postpartum group session Participants completed the following questionnaires on psychological distress, eating patterns, and exercise at baseline and 8 weeks post-intervention.

| Control group Baseline 2.1 (0.7) MF Group Baseline 2.1 (0.6) | Control group 2.0 (0.6) MF Group 2.0 (0.7) | Control group Baseline 6.8 (4.9) MF Group Baseline 7.6 (5.6) Depression (β = −2.00; 95% CI = −3.39, 0.62) | Control group 6.1 (4.5) MF Group 4.5 (3.7) * | Control group Baseline 18.4 (6.6) MF Group Baseline 19.1 (6.6) Perceived stress (β = −2.01, 95% CI = −3.93, −0.09) | Control group 17.0 (7.4) MF Group 15.6 (5.8) * * Sample size varied due to missing data, ranging from 167 to 170 for the final sample with complete data for each measure. * p < 0.05 |

| Goodman et al., 2014 USA [34] | Experimental study Analysis of CALM Pregnancy programme for pregnant women with generalised anxiety disorder, high levels of anxiety, or symptoms of worry. | n = 24 of whom 23 attended an average of 6.96 sessions) 21 women (87.5%) attended at least 6 of the 8 sessions Mean age (SD) = 33.5 (4.4) years Range: 27–45 years | 8 weekly group sessions of 2 h (groups of 6–12 women) 30–40 min of home practice daily during the intervention. Instruments used:

| Baseline n = 11 (47.8%) | n = 7 (63.6%) (recovered) n = 2 (18.2%) (Significantly improved) | Baseline n = 23 (100%) | Post-MF n = 11 (47.8%) (recovered) n = 5 (21.7%) (significantly improved) | --- | --- |

| Guardino et al., 2014 USA [35] | Controlled randomised clinical trial (experimental study) MF-based intervention for women experiencing high levels of perceived stress and anxiety during pregnancy. | n = 47 Divided into two groups: Intervention group n = 24 Mindful awareness practical classes Completed the intervention: n = 20 Control group (n = 23) Completed the intervention: n = 20 Mean age of participants: 33.13 years (SD = 4.79) | Six weeks of 2 h MF classes at the Mindful Institute of the Semel Institute at UCLA. The following online questionnaires were completed immediately post-intervention (Time 1) and 6 weeks later (Time 2). Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire FFMQ Perceived Stress Scale PSS Pregnancy Specific Anxiety PSA Pregnancy-Related Anxiety Scale PRA Spielberger’s Trait Anxiety Inventory STAI The participants in the control group were given a booklet each trimester of pregnancy with information on childbirth, postpartum feeding, and infant care. | MF Group Baseline PSA 11.63 (2.96) Control group PSA 10.70 (2.79) MF Group Baseline STAI 45.69 (7.64) Control group Baseline STAI 44.37 (10.98) | MF Group POST 1 PSA 7.65 (1.73) POST 2 PSA 9.20 (2.35) Control group POST 1 PSA 8.95 (3.00) Control group POST 2 PSA 9.00 (2.23) MF Group POST 1 STAI 39.47 (6.27) POST 2 STAI 38.11 (8.78) Control group POST 1 STAI 37.35 (11.51) POST 2 STAI 36.19 (10.84) | --- | --- | MF Group Baseline PSS 41.81 (6.00) Control group Baseline PSS 39.91 (8.55) | MF Group POST 1 PSS 37.30 (5.38) POST 2 PSS 36.17 (5.90) Control group POST 1 PSS 35.80 (8.01) POST 2 PSS 37.42 (7.27) |

| Kalmbach et al., 2023 USA [36] | Controlled randomised clinical trial Study conducted to determine whether cognitive behavioural therapy (the Perinatal Understanding of Mindful Awareness for Sleep (PUMAS) programme) is effective in combating prenatal insomnia, depression, and cognitive arousal. | One group: n= 12 11 PUMAS patients (91.7%) completed the 6 sessions Age = 22 to 36 years (30.33 ± 4.23) (Mean ± SD) | 6 weekly individual telemedicine (i.e., video) sessions of 60 min. PUMAS The results were evaluated by:

Self-efficacy in MF meditation was assessed after the intervention. | --- | --- | pre PUMAS Baseline EPDS 8.67 ± 5.33 | post- PUMAS EPDS 3.42 ± 2.75 | --- | --- |

| Kundarti et al., 2023 Indonesia [37] | Quasi-experimental study (randomised control study) MF-based intervention to measure and reduce levels of anxiety and cortisol during pregnancy. | n = 70 Divided into two groups: Intervention group (n = 35) Mean age: 23.80 ± 2.96 years Control group n = 35 Mean age: 25.31 ± 3.03 years | Eight 2 h MF sessions, once weekly. The PASS questionnaire was completed. A DBC blood cortisol test with competitive ELISA I was performed, after obtaining informed consent. Data on anxiety and blood cortisol were collected at baseline and after 8 weeks (post-test). | MF Group Baseline 34.77 (17.26) Control group 39.23 (20.56) | MF Group POST 12.83 (8.29) Control group 30.69 (16.39) | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Nejad et al., 2021 Iran [38] | Randomised clinical trial To evaluate how an MF-based stress reduction programme influences stress, anxiety, and depression resulting from an unplanned pregnancy. | n = 60 with unplanned pregnancy Divided into two groups: Intervention group (n = 30) Mean age: 28.93 ± 5.62 years Control group n = 30 Mean age: 29.30 ± 6.32 years | 8 MF-based stress reduction sessions (2 h/session, once weekly), plus home practice and recorded audio. Results were assessed using the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale DASS-21, at baseline and after the 8 sessions. | MF Group Baseline 13.20 (7.05) Control group 12.20 (6.06) | MF Group POST 3.33 (2.98) Control group 13.6 (6.54) | MF Group Baseline 19.80 (16.13) Control group 18.8 (7.95) | MF Group POST 4.6 (5.09) Control group 17.86 (9.9) | MF Group Baseline 23.86 (0.859) Control group 25.40 (8.07) | MF Group Baseline 8.86 (5.45) Control group 23.86 (8.74) |

| Pan et al., 2023 Taiwan [39] | Longitudinal randomised clinical trial Testing the effect of a perinatal MF programme on stress, anxiety, depression, and bonding in women with a perinatal mood and anxiety disorder. | n = 102 Divided into two groups: Intervention group (n = 51) Completed intervention n = 33 Mean age (SD): 33.52 ± 4.91 years Control group n = 51 Completed intervention n = 33 Mean age (SD): 32.88 ± 3.90 years | 8-week prenatal MF programme, with one 2 h session each week. Results were assessed using the following instruments:

Efficacy of the intervention was assessed:

Depression and stress were measured at T0, T1, T2, T3, and T4. Anxiety was measured at T0, T1, and T2. | MF Group Baseline 24.21 Control group 22.69 | MF Group POST 17.53 T1 (B = 0.84. p < 0.001. ES = 0.74; large effect) T2 (B = 0.85. p < 0.001; ES = 0.47; moderate effect) Control group 18.05 | MF Group Baseline 12.88 (2.99) Control group 13.70 (3.78) | MF Group Baseline 9.12 (T1) 9.18 (T2) 7.18 (T3) 9.43 (T4) This decrease was significant for the MF group at T1 (B = −0.69. p < 0.001. ES = 0.52): T2 (B = 0.73. p < 0.001. ES = 0.22). (no effect) Control group 11.67 (T1) 10.36 (T2) 9.79 (T3) 10.55 (T4) | MF Group Baseline 18.45 (4.91) Control group 18.97 (3.78) | MF Group Baseline 14.18 (T1) 14.85 (T2) 13.88 (T3) 14.40 (T4) (slight) The decrease was significant for the MF group at T1 (B = −0.26, p < 0.001, ES = 0.53) and T2 (B = 0.62, p < 0.001, ES = 0.29). After delivery, the z scores for PSS fell in the MF group (B = 0.62, p < 0.001; B = −0.66, p < 0.001) and the effect size was small to moderate at T3 and T4 (ES = 0.56; 0.21) Control group 16.76 (T1) 16.12 (T2) 16.64 (T3) 15.57 (T4) |

| Zhang et al., 2023 China [40] | Randomised clinical trial Conducted to determine the effectiveness of a guided digital self-help MF-based intervention in reducing maternal psychological distress and improving the child’s neuropsychological performance. | n = 160 Randomly divided into two groups: Digital GSH-MBI group n = 80 Mean age (SD) 30.36 (4.65) years Completed intervention: n = 69 11 did not complete Control group n = 80 Mean age (SD) 30.21 (3.93) years Completed intervention: n = 66 14 did not complete Dropout rate: 25/160, 15.6% Mean age (SD) 30 (4.29) years | 6 weeks/6 modules. Guided digital self-help MF-based intervention, using 10–20 m video modules via WeChat mini-program. On the first day of each week, a video was screened. On the remaining 6 days of each week, the participants had formal audio-based practices and assignments focused on mindful breathing and body scanning, plus informal MF practices in everyday life or 3 min space-to-breathe exercises. Outcomes were assessed at 6 weeks and at 6 months postpartum, using the following scales and questionnaires.

Assessment schedule: T1: Baseline (12–20 weeks’ gestation) T2: Immediately after the intervention (approx. 20–28 weeks’ gestation) T3: Before birth (36–37 weeks’ gestation) T4: At 6 weeks postpartum T5: At 3 months postpartum T6: At 6 months postpartum. The effect of the intervention was analysed using generalised estimating equations. | Control group Baseline 5.80 (3.14) (T1) 5.61 (3.04) (T2) 6.18 (3.83) (T3) 7.31 (4.49) (T4) 5.90 (4.71) (T5) 5.90 (4.76) (T6) R/C Pregnancy 21.88 (4.64) (T1) 23.15 (5.55) (T2) 24.22 (5.77) (T3) | MF group Post 5.56 (2.61) (T1) 3.14 (2.74) (T2) 3.32 (3.19) (T3) 4.49 (3.63) (T4) 4.34 (3.31) (T5) 3.75 (3.28) (T6) Wald χ25 = 24.7; p < 0.001) R/C Pregnancy 22.61 (4.53) (T1) 19.47 (4.03) (T2) 19.41 (4.98) (T3) Wald χ22 = 46.5; p < 0.001) | Control group Baseline 9.43 (3.26) (T1) 7.86 (5.07) (T2) 8.60 (5.58) (T3) 9.25 (6.34) (T4) 8.27 (6.31) (T5) 8.45 (6.53) (T6) | MF group Baseline 8.91 (3.54) (T1) 5.21 (4.46) (T2) 4.48 (4.22) (T3) 5.81 (5.27) (T4) 5.25 (4.47) (T5) 5.54 (5.44) (T6) (Wald χ25 =20.6; p = 0.001) | --- | --- |

| Zhang et al. (2021) China [41] | Randomised clinical trial Conducted to examine the effectiveness of an MF-based intervention in reducing prenatal stress compared to participation in a health education (HE) group. | n = 108 Divided into two groups: Intervention group: n = 54 Control group n = 54 Mean age (SD) 28.85 (3.60) years Range: 21–42 years | 30 m weekly sessions for 4 weeks via WeChat plus 30–45 m daily MF practice. Depression and anxiety were assessed using EPDS and GAD-7 in the last week and in the final 2 weeks. Perceived stress was assessed with the Perceived Stress Scale-4 PSS-4 The severity of fatigue was assessed using the Fatigue Severity Scale FSS The effect of the intervention was analysed using generalised estimating equations. Assessment schedule: T1: Baseline T2: Immediately after the intervention T3: 15 weeks after the intervention | Control group 5.63 (3.06) (T1) 5.98 (3.74) (T2) 5.90 (3.37) (T3) | MF Group 5.73 (2.66) (T1) 4.56 (2.74) (T2) 4.83 (1.78) (T3) The main effects of study group, time, and group-time interaction for anxiety were not significant: (Wald v2 = 3.46. p = 0.063; Wald v2 = 1.49. p = 0.475; Wald v2 ¼5.16. p = 0.076. | Control group 10.35 (2.64) (T1) 9.54 (3.90) (T2) 10.14 (4.33) (T3) | MF Group 9.88 (3.21) (T1) 7.17 (3.81) (T2) 7.39 (3.29) (T3) Main significant effect for the group: (Wald v2 = 5.00. p = 0.005) and for time (Wald v2 ¼22.85. p < 0.001). and one non-significant effect for the group-time interaction (Wald v2 = 6.01. p = 0.049) for depression. | Control group 5.86 (2.15) (T1) 6.59 (5.53) (T2) 6.95 (2.77) (T3) | MF Group 5.51 (2.25) (T1) 4.38 (2.45) (T2) 3.14 (2.07) (T3) Main significant effect for the group (Wald v2 = 30.47, p < 0.001) and a main non-significant effect for time (Wald v2 = 2.40, p = 0.301), and a significant effect for the group—perceived stress interaction (Wald v2 ¼26.94, p < 0.001). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vázquez-Lara, M.D.; Ruger-Navarrete, A.; Mohamed-Abdel-Lah, S.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Fernández-Carrasco, F.J.; Rodríguez-Díaz, L.; Caparros-Gonzalez, R.A.; Palomo-Gómez, R.; Riesco-González, F.J.; Vázquez-Lara, J.M. The Impact of Mindfulness Programmes on Anxiety, Depression and Stress During Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1378. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121378

Vázquez-Lara MD, Ruger-Navarrete A, Mohamed-Abdel-Lah S, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Fernández-Carrasco FJ, Rodríguez-Díaz L, Caparros-Gonzalez RA, Palomo-Gómez R, Riesco-González FJ, Vázquez-Lara JM. The Impact of Mindfulness Programmes on Anxiety, Depression and Stress During Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare. 2025; 13(12):1378. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121378

Chicago/Turabian StyleVázquez-Lara, María Dolores, Azahara Ruger-Navarrete, Samia Mohamed-Abdel-Lah, José Luis Gómez-Urquiza, Francisco Javier Fernández-Carrasco, Luciano Rodríguez-Díaz, Rafael A. Caparros-Gonzalez, Rocío Palomo-Gómez, Francisco Javier Riesco-González, and Juana María Vázquez-Lara. 2025. "The Impact of Mindfulness Programmes on Anxiety, Depression and Stress During Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Healthcare 13, no. 12: 1378. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121378

APA StyleVázquez-Lara, M. D., Ruger-Navarrete, A., Mohamed-Abdel-Lah, S., Gómez-Urquiza, J. L., Fernández-Carrasco, F. J., Rodríguez-Díaz, L., Caparros-Gonzalez, R. A., Palomo-Gómez, R., Riesco-González, F. J., & Vázquez-Lara, J. M. (2025). The Impact of Mindfulness Programmes on Anxiety, Depression and Stress During Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare, 13(12), 1378. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121378