Turkish Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Validity, and Reliability of the Physical Activity and Social Support Scale (PASSS) in Physically Active Healthy Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Translation and Cultural Adaptation

2.3. Outcome Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Translation Process of the PASSS

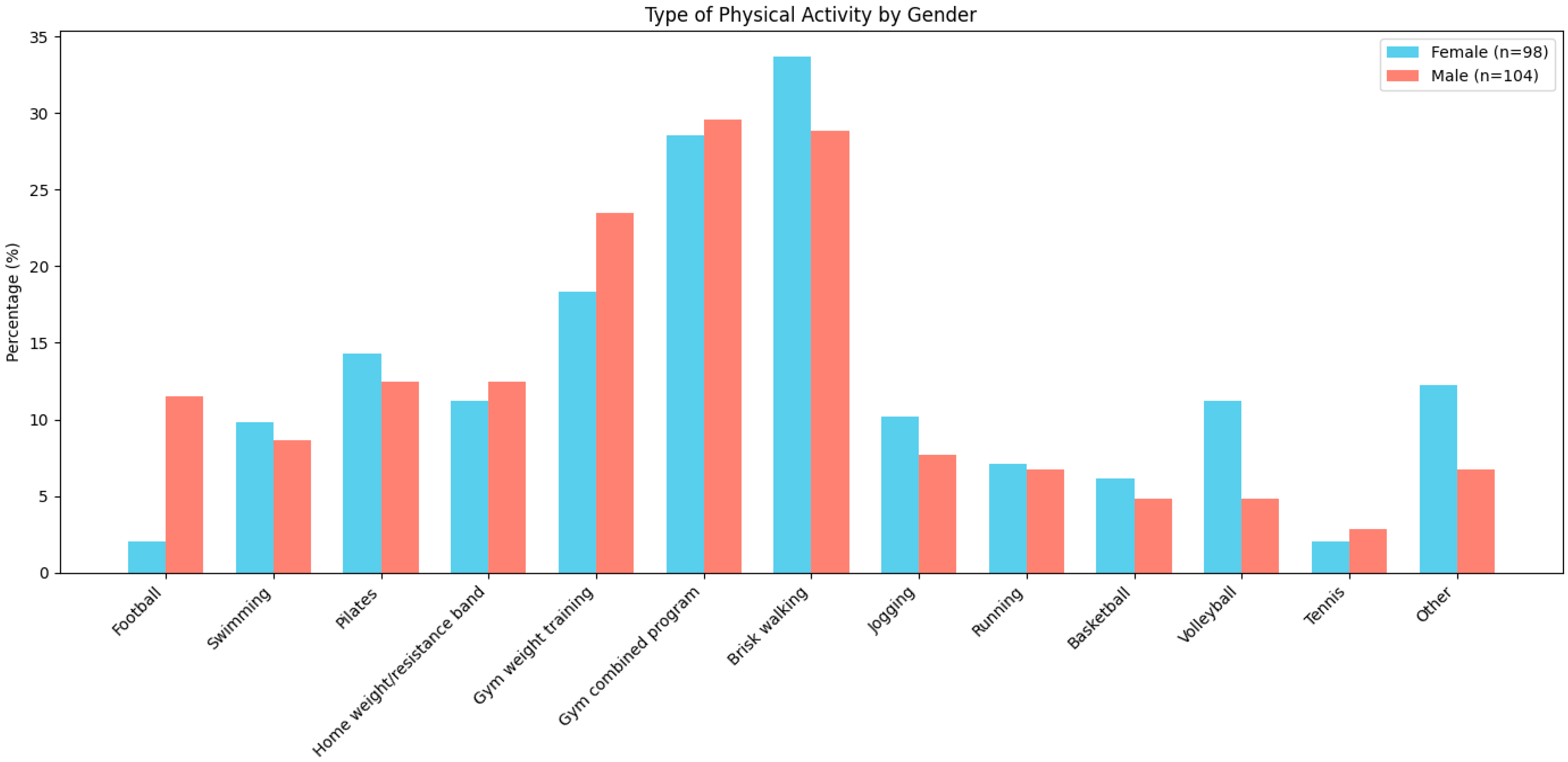

3.2. Sample Characteristics

3.3. Internal Consistency

3.4. Test–Retest Reliability

3.5. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

- -

- Emotional Support (items 1–4): Represents social interactions through which participants feel emotionally supported.

- -

- Validation Support (items 5–8): Includes feedback and comparisons that help participants assess their competence relative to others.

- -

- Instrumental Support (items 17–20): Refers to tangible assistance facilitating participation in physical activity (e.g., equipment, childcare, transportation).

- -

- Companionship Support (items 13–16): Reflects feelings of social belonging and being part of a group.

- -

- Informational Support (items 9–12): Captures perceptions of receiving and sharing information related to physical activity.

3.6. Construct Validity

3.7. Convergent and Divergent Validity

3.8. Ceiling and Floor Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Set of Recommendations on the Marketing of Foods and Non-Alcoholic Beverages to Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241500210 (accessed on 15 June 2010).

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, R. Modeling health behavior change: How to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, W.C.; Baranowski, T.O.M.; Sallis, J.F. Family determinants of childhood physical activity: A social-cognitive model. In Advances in Exercise Adherence; Dishman, R.K., Ed.; Human Kinetics Publishers: Champaign, IL, USA, 1994; pp. 319–342. [Google Scholar]

- Trost, S.G.; Owen, N.; Bauman, A.E.; Sallis, J.F.; Brown, W. Correlates of adults’ participation in physical activity: Review and update. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 1996–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Gottlieb, B.H.; Underwood, L.G. Measuring and intervening in social support. In Social Relationships and Health; Cohen, S., Underwood, L.G., Gottlieb, B.H., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, A.E.; Reis, R.S.; Sallis, J.F.; Wells, J.C.; Loos, R.J.; Martin, B.W. Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Correlates of physical activity: Why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet 2012, 380, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, L.H.; Kreuter, M.W. Social environment and physical activity: A review of concepts and evidence. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarapicchia, T.M.F.; Amireault, S.; Faulkner, G.; Sabiston, C.M. Social support and physical activity participation among healthy adults: A systematic review of prospective studies. Int. Rev. Sport. Exerc. Psychol. 2017, 10, 50–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, L.; Tan, K.; Diener, E.; Gonzalez, E. Social relations, health behaviors, and health outcomes: A survey and synthesis. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2013, 5, 28–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, L.F.; Glass, T. Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. In Social Epidemiology; Berkman, L.F., Kawachi, I., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 137–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Grossman, R.M.; Pinski, R.B.; Patterson, T.L.; Nader, P.R. The development of scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors. Prev. Med. 1987, 16, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, T.E.; McAuley, E. Social support and efficacy cognitions in exercise adherence: A latent growth curve analysis. J. Behav. Med. 1993, 16, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malecki, C.K.; Demaray, M.K. Measuring perceived social support: Development of the child and adolescent social support scale (CASS). Psychol. Sch. 2002, 39, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Farias Júnior, J.C.; Mendonça, G.; Florindo, A.A.; de Barros,, M.V. Reliability and validity of a physical activity social support assessment scale in adolescents—ASAFA Scale. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2014, 17, 355–370, (In English, In Portuguese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golaszewski, N.M.; Bartholomew, J.B. The development of the physical activity and social support scale. J. Sport. Exerc. Psychol. 2019, 41, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Herold, F.; Kramer, A.F.; Ng, J.L.; Hossain, M.M.; Chen, J.; Kuang, J. Validity and reliability of the physical activity and social support scale among Chinese established adults. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2023, 53, 101793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazrati, Z.; Ranjbari, S.; Baniasadi, T.; Khajehaflaton, S. Effects of social support on participation of children with ADHD in physical activity: Mediating role of emotional wellbeing. J. Pediatr. Perspect. 2022, 10, 16880–16886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamilla, R.A.; Kaushal, N.; Bigatti, S.M.; Keith, N.R. Comparing barriers and facilitators to physical activity among underrepresented minorities: Preliminary outcomes from a mixed-methods study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2025, 22, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capan, M.; Bigelow, L.; Kathuria, Y.; Paluch, A.; Chung, J. Analysis of multi-level barriers to physical activity among nursing students using regularized regression. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, N.H.; de Cerqueira Santos, A.; Mintrone, R.; Turner, K.; Sutton, S.K.; O’Connor, T.; Huang, J.; Lael, M.; Cruff, S.; Grassia, K.; et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and outcomes of Project Rally: Pilot study of a YMCA-based pickleball program for cancer survivors. Healthcare 2025, 13, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golaszewski, N.M.; LaCroix, A.Z.; Hooker, S.P.; Bartholomew, J.B. Group exercise membership is associated with forms of social support, exercise identity, and amount of physical activity. Int. J. Sport. Exerc. Psychol. 2022, 20, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçükibiş, H.F.; Eskiler, E. Social support scale in physical activities: Turkish adaptation, validity and reliability study. J. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2019, 6, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, S.; Çakır, B.; Kılınç, F.N.; Vergili, Ö.; Erdem, Y. Reliability and validity study of the Turkish version of the Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale for Healthy Behaviors. Asian Nurs. Res. 2018, 12, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldızer, G.; Bilgin, E.; Korur, E.N.; Novak, D.; Demirhan, G. The association of various social capital indicators and physical activity participation among Turkish adolescents. J. Sport. Health Sci. 2018, 7, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timurtaş, E.; Selçuk, H.; Çınar, E.; Demirbüken, İ.; Sertbaş, Y.; Polat, M.G. Personal, social, and environmental correlates of physical activity and sport participation in an adolescent Turkish population. Bull. Fac. Phys. Ther. 2022, 27, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B.; Bot, S.D.; de Boer, M.R.; van der Windt, D.A.; Knol, D.L.; Dekker, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eker, D. Cok boyutlu algilanan sosyal destek olceginin gozden gecirilmis formunun faktor yapisi, gecerlik ve guvenirligi. Turk. Psikiyatri Derg. 2001, 12, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Saglam, M.; Arikan, H.; Savci, S.; Inal-Ince, D.; Bosnak-Guclu, M.; Karabulut, E.; Tokgozoglu, L. International physical activity questionnaire: Reliability and validity of the Turkish version. Percept. Mot. Skills. 2010, 111, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soylu, C.; Kütük, B. Reliability and validity of the Turkish version of SF-12 health survey. Turk. Psikiyatri Derg. 2022, 33, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, S. Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient. J. Mood Disord. 2016, 6, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busschaert, C.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Van Holle, V.; Chastin, S.F.; Cardon, G.; De Cocker, K. Reliability and validity of three questionnaires measuring context-specific sedentary behaviour and associated correlates in adolescents, adults and older adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- DeVet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.; Mokkink, L.B.; Knol, D.L. Measurement in Medicine: A Practical Guide; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The Who Stepwise Approach to Noncommunicable Disease Risk Factor Surveillance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Minister of Health of Turkey. Turkey Nutrition and Health Research; Minister of Health of Turkey: Ankara, Turkey, 2014. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Tek, N.A.; Mortas, H.; Arslan, S.; Tatar, T.; Köse, S. The physical activity level is low in young adults: A pilot study from Turkey. Am. J. Public. Health Res. 2020, 8, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savcı, S.; Öztürk, M.; Arıkan, H.; İnce, D.; Tokgözoğlu, L. Physical activity levels of university students. Arch. Turk. Soc. Cardiol. 2006, 34, 166–172. [Google Scholar]

- Kağıtçıbaşı, Ç. Family and Human Development Across Cultures: A View from the Other Side; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Yalçın, M.; Erel, Ö. Sosyal medya kullanımı ve kültürel farklılıklar: Türkiye’deki sosyal medya alışkanlıklarının incelenmesi. İletişim Araştırmaları Dergisi 2020, 34, 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Mendonça, G.; Cheng, L.A.; Mélo, E.N.; de Farias Júnior, J.C. Physical activity and social support in adolescents: A systematic review. Health Educ. Res. 2014, 29, 822–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | n = 202 |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean ± SD | 26.5 ± 6.1 |

| Range | 18–53 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 104 (51.5%) |

| Female | 98 (45.5%) |

| BMI | 23.3 ± 3.2 |

| Education | |

| High School | 5 (2.5%) |

| University | 159 (78.7%) |

| Master’s Degree | 38 (18.8%) |

| Activity Level According to IPAQ-SF | |

| Inactive | 11 |

| Minimally active | 102 |

| Active | 89 |

| Measure | Minimum | Maximum | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| IPAQ-SF total | 396 | 20,052 | 3393.62 (2692.02) |

| IPAQ-SF moderate | 0 | 2400 | 640.33 (516.69) |

| IPAQ-SF vigorous | 0 | 17,280 | 1641.58 (1964.67) |

| IPAQ-SF walking | 66 | 8316 | 1168.80 (1262.29) |

| MSPSS | 22 | 84 | 69.17 (13.47) |

| PCS-12 | 23 | 64 | 52.58 (0.50) |

| MCS-12 | 15 | 58 | 41.61 (0.62) |

| PASSS total | 1 | 7 | 4.90 (0.94) |

| PASSS emotional | 1 | 7 | 5.40 (1.44) |

| PASSS companionship | 1 | 7 | 5.23 (1.49) |

| PASSS instrumental | 1 | 7 | 5.41 (1.28) |

| PASSS informational | 1 | 7 | 4.95 (1.22) |

| PASSS validation | 1 | 7 | 3.54 (1.61) |

| Measure | PASSS Total (rho) | PASSS Emotional (rho) | PASSS Companionship (rho) | PASSS Instrumental (rho) | PASSS Informational (rho) | PASSS Validation (rho) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPAQ-SF total | 0.27 * | 0.05 | 0.34 * | 0.36 * | 0.06 | 0.11 |

| IPAQ-SF moderate | 0.17 * | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.17 * |

| IPAQ-SF vigorous | 0.22 * | 0.05 | 0.32 * | 0.21 * | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| MSPSS | 0.37 * | 0.37 * | 0.23 * | 0.41 * | 0.27 * | 0.10 |

| PCS-12 | 0.15 * | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.23 * |

| MCS-12 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Analay Akbaba, Y.; Aksan Sadıkoğlu, B.; Menengiç, K.N.; Besim Atakan, M.; Tongar, D.; Tokgoz, G.; Ayas, A.; Tongar, S.Ş.; Akgüller Eker, T. Turkish Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Validity, and Reliability of the Physical Activity and Social Support Scale (PASSS) in Physically Active Healthy Adults. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1343. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111343

Analay Akbaba Y, Aksan Sadıkoğlu B, Menengiç KN, Besim Atakan M, Tongar D, Tokgoz G, Ayas A, Tongar SŞ, Akgüller Eker T. Turkish Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Validity, and Reliability of the Physical Activity and Social Support Scale (PASSS) in Physically Active Healthy Adults. Healthcare. 2025; 13(11):1343. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111343

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnalay Akbaba, Yıldız, Büşra Aksan Sadıkoğlu, Kübra Nur Menengiç, Meltem Besim Atakan, Doğukan Tongar, Gulfidan Tokgoz, Alper Ayas, Sahra Şirvan Tongar, and Tuğba Akgüller Eker. 2025. "Turkish Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Validity, and Reliability of the Physical Activity and Social Support Scale (PASSS) in Physically Active Healthy Adults" Healthcare 13, no. 11: 1343. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111343

APA StyleAnalay Akbaba, Y., Aksan Sadıkoğlu, B., Menengiç, K. N., Besim Atakan, M., Tongar, D., Tokgoz, G., Ayas, A., Tongar, S. Ş., & Akgüller Eker, T. (2025). Turkish Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Validity, and Reliability of the Physical Activity and Social Support Scale (PASSS) in Physically Active Healthy Adults. Healthcare, 13(11), 1343. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111343