Ecological Beeswax Breast Pads Promote Breastfeeding in First-Time Mothers from the Valencian Community (Spain): A Randomized Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- First-time mothers during the third trimester of pregnancy with a desire to breastfeed and who signed the informed consent.

- Only participants who attended the WHO educational program and those in the intervention group used the breast areolas daily.

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Before starting the study, exclusion criteria were established: atopy and/or dermatological problems; mental health conditions; allergies to bee products; and not speaking or understanding Spanish.

- The following cases were eliminated as exclusion criteria, although they were not designed as exclusion criteria: pregnant woman who did not go to the scheduled hospital to give birth; hospitalization of the newborn for any reason; and did not attend the midwife’s office during the days following postpartum discharge and were considered losses.

2.3. Sampling Size

2.4. Intervention

2.5. Main Variable

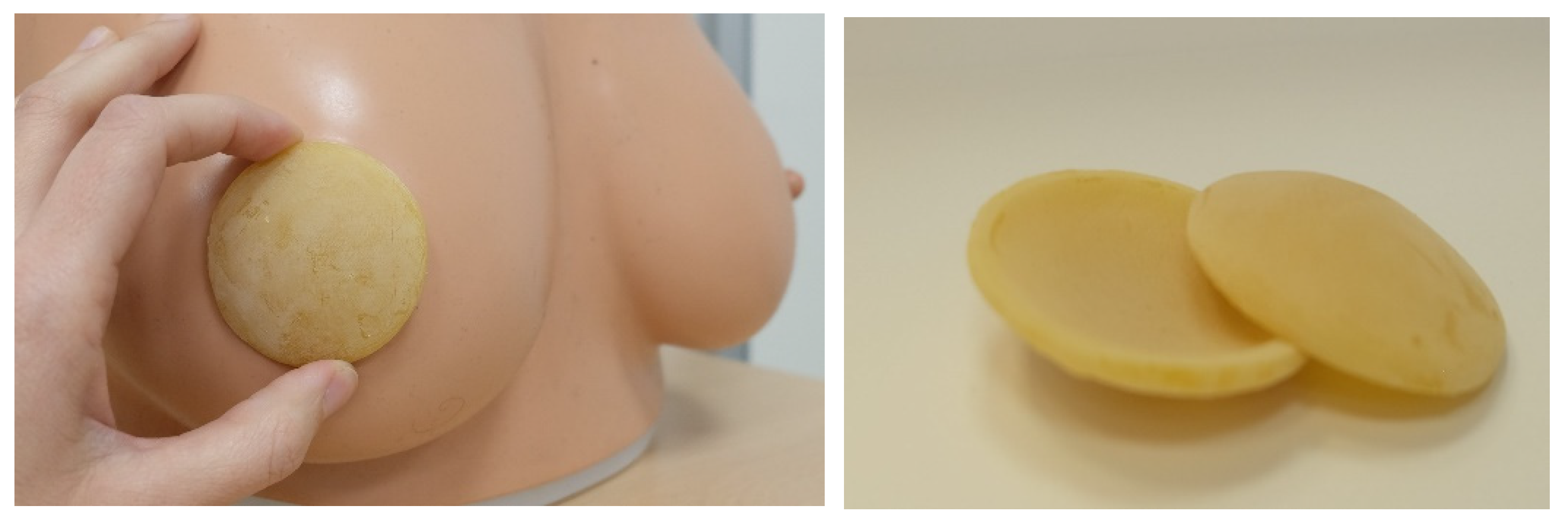

2.6. Description of the Beeswax Discs (Mamaceram®)

3. Ethical Issues

4. Statistical Analysis

5. Results

Characteristics of the Participants

6. Discussion

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions

9. Implications for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Infant and Young Child Feeding. 2023 Dec. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Thompson, J.M.D.; Tanabe, K.; Moon, R.Y.; Mitchell, E.A.; McGarvey, C.; Tappin, D.; Blair, P.S.; Hauck, F.R. Duration of Breastfeeding and Risk of SIDS: An Individual Participant Data Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20171324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, N.T.; Li, F.; Lee-Sarwar, K.A.; Tun, H.M.; Brown, B.P.; Pannaraj, P.S.; Bender, J.M.; Azad, M.B.; Thompson, A.L.; Weiss, S.T.; et al. Meta-analysis of effects of exclusive breastfeeding on infant gut microbiota across populations. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.; Raman, G.; Trikalinos, T.; Lau, J.; Ip, S. Interventions in primary care to promote breastfeeding: An evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008, 149, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patro-Gołąb, B.; Zalewski, B.M.; Polaczek, A.; Szajewska, H. Duration of Breastfeeding and Early Growth: A Systematic Review of Current Evidence. Breastfeed. Med. 2019, 14, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroon, S.; Das, J.K.; Salam, R.A.; Imdad, A.; Bhutta, Z.A. Breastfeeding promotion interventions and breastfeeding practices: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13 (Suppl. S3), S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.L.; Lu, D.F.; Tsay, P.K. Rooming-In and Breastfeeding Duration in First-Time Mothers in a Modern Postpartum Care Center. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, L.; Hand, I.L.; Noble, A. The Effect of Breastfeeding in the First Hour and Rooming-In of Low-Income, Multi-Ethnic Mothers on In-Hospital, One and Three Month High Breastfeeding Intensity. Children 2023, 10, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Chillerón, M.J.; Mena-Tudela, D.; Cervera-Gasch, Á.; González-Chordá, V.M.; Soriano-Vidal, F.J.; Quesada, J.A.; Castro-Sánchez, E.; Vila-Candel, R. Influence of Health Literacy on Maintenance of Exclusive Breastfeeding at 6 Months Postpartum: A Multicentre Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagla, M.; Mrvoljak-Theodoropoulou, I.; Vogiatzoglou, M.; Giamalidou, A.; Tsolaridou, E.; Mavrou, M.; Dagla, C.; Antoniou, E. Association between Breastfeeding Duration and Long-Term Midwifery-Led Support and Psychosocial Support: Outcomes from a Greek Non-Randomized Controlled Perinatal Health Intervention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, C.; McCormick, F.M.; Renfrew, M.J.; Wade, A.; King, S.E. Support for breastfeeding mothers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007, 1, CD001141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. 2003. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/42590/9241562218.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2017).

- Aldalili, A.Y.A.; El Mahalli, A.A. Research Title: Factors Associated with Cessation of Exclusive Breastfeeding. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 14, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babakazo, P.; Bosonkie, M.; Mafuta, E.; Mvuama, N.; Mapatano, M.A. Common breastfeeding problems experienced by lactating mothers during the first six months in Kinshasa. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renfrew, M.J.; McCormick, F.M.; Wade, A.; Quinn, B.; Dowswell, T. Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 5, CD001141, Update in: Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2, CD001141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Trivedi, D. Cochrane Review Summary: Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2018, 19, 529–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohandas, S.; Andrenacci, P.; Duque, T. Summary of a Cochrane review: Effect of breastfeeding support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies. Explore 2023, 19, 874–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, J.C.; Ashton, E.; Hardwick, C.M.; Rowan, M.K.; Chia, E.S.; Fairclough, K.A.; Menon, L.L.; Scott, C.; Mather-McCaw, G.; Navarro, K.; et al. Nipple Pain in Breastfeeding Mothers: Incidence, Causes and Treatments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 12247–12263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, A.; Rahimi, V.B.; Soheili-Far, S.; Askari, N.; Rahmanian-Devin, P.; Sanei-Far, Z.; Sahebkar, A.; Rakhshandeh, H.; Askari, V.R. A Systematic Review on Prevention and Treatment of Nipple Pain and Fissure: Are They Curable? J. Pharmacopunct. 2018, 21, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE (Instituto Nacional de Estadística). Encuesta Nacional de Salud. 26 June 2018. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176783&menu=resultados&idp=1254735573175#_tabs-1254736195650 (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Martín-Ramos, S.; Domínguez-Aurrecoechea, B.; García Vera, C.; Lorente García Mauriño, A.M.; Sánchez Almeida, E.; Solís-Sánchez, G. Breastfeeding in Spain and the factors related to its establishment and maintenance: LAyDI Study (PAPenRed). Aten Primaria 2024, 56, 102772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund. Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Breastfeeding Policy Brief (WHO/NMH/NHD/14.7); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/149022/WHO_NMH_NHD_14.7_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Kurek-Górecka, A.; Górecki, M.; Rzepecka-Stojko, A.; Balwierz, R.; Stojko, J. Bee Products in Dermatology and Skin Care. Molecules 2020, 25, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nong, Y.; Maloh, J.; Natarelli, N.; Gunt, H.B.; Tristani, E.; Sivamani, R.K. A review of the use of beeswax in skincare. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 2166–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placzek, M.; Friede, T. Clinical trials with nested subgroups: Analysis, sample size determination and internal pilot studies. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2018, 27, 3286–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RNAO (Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario Breastfeeding). Promoting and Supporting the Initiation, Exclusivity, and Continuation of Breastfeeding in Newborns, Infants and Young Children. 2018. Available online: https://rnao.ca/bpg/guidelines/breastfeeding-promoting-and-supporting-initiation-exclusivity-and-continuation (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- UNICEF. From the First Hour of Life. Making the Case for Improved infant And Young Child Feeding Everywhere. 2016. Available online: https://healthynewbornnetwork.org/resource/2016/from-the-first-hour-of-life-making-the-case-for-improved-infant-and-young-child-feeding-everywhere/ (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Regan, A.K.; Swathi, P.A.; Nosek, M.; Gu, N.Y. Measurement of Health-Related Quality of Life from Conception to Postpartum Using the EQ-5D-5L Among a National Sample of US Pregnant and Postpartum Adults. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2023, 21, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Hoz Cáceres, D.; Jiménez-García, J.F.; Rosanía-Arroyo, S.; Vásquez-Munive, M.; Álvarez-Miño, L.; Jiménez-García, J.F.; Rosanía-Arroyo, S.; Vásquez-Munive, M.; Álvarez-Miño, L. Systematic review of the causes and treatments for nipple cracks during breastfeeding. Entramado 2019, 15, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Tomori, C.; Hernández-Cordero, S.; Baker, P.; Barros, A.J.D.; Bégin, F.; Chapman, D.J.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M.; McCoy, D.; Menon, P.; et al. 2023 Lancet Breastfeeding Series Group. Breastfeeding: Crucially important, but increasingly challenged in a market-driven world. Lancet 2023, 401, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.S.; Vieira, F.; Valadares Guimarães, J.; Del’Angelo Aredes, N.; Hetze Campbell, S. Lanolina y educación para la salud en la prevención de dolor y lesiones en los pezones: Ensayo clínico aleatorizado. Enf. Clin. 2021, 31, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad; Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Guía de Práctica Clínica Sobre Lactancia Materna. 2017. Available online: https://www.aeped.es/sites/default/files/guia_de_lactancia_materna.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Perić, O.; Pavičić Bošnjak, A.; Mabić, M.; Tomić, V. Comparison of Lanolin and Human Milk Treatment of Painful and Damaged Nipples: A Randomized Control Trial. J. Hum. Lact. 2023, 39, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Cordero, M.; Villar, N.M.; Barrilao, R.G.; Cortés, M.E.; López, A.M. Application of Extra Virgin Olive Oil to Prevent Nipple Cracking in Lactating Women. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2015, 12, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agea-Cano, I.; Calero-García, M.J.; Fuentes, A.G.C.; Linares-Abad, M. Eficacia del aceite de oliva ecológico en las grietas del pezón y dolor durante el amamantamiento. Evidentia 2021, 18, e13849. [Google Scholar]

- Nageeb, H.; Fadel, E.; Hassan, N. Olive oil on nipple trauma among lactating mothers. Mansoura Nurs. J. 2018, 5, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmawgoud Ahmed, N.; Ibrahim Badawy Othman, A.; Ahmed Kanona, A.; Mostafa Amer, H.; Salah Shalaby, N.; Bassuoni Elsharkawy, N. A randomized Controlled Study on the Effects of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Compared to Breast Milk on Painful and Damaged Nipples During Lactation. Egypt. J. Health Care 2020, 11, 702–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Control Group (n = 69); n (%); Mean ± SD | Intervention Group (n = 77); n (%); Mean ± SD | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31.8 ± 4.7 | 31.2 ± 5.2 | 0.415 |

| Goldberg Depression (pre) | 1.9 ± 1.8 | 1.9 ± 1.8 | 0.930 |

| Goldberg Anxiety (pre) | 3.0 ± 2.3 | 3.2 ± 2.3 | 0.639 |

| EQ5D mobility (pre) | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.118 |

| EQ5D personal care (pre) | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.881 |

| EQ5D activities of daily living (pre) | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.254 |

| EQ5D pain/discomfort (pre) | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 0.508 |

| EQ5D anxiety/depression (pre) | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 0.996 |

| Self-perception of health status (pre) | 81.9 ± 13.1 | 85.5 ± 13.1 | 0.126 |

| Prepartum discomfort | 25 (36.2) | 31 (40.3) | 0.617 |

| Working outside the home | 45 (66.2) | 44 (57.9) | 0.307 |

| Inverted nipple | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.6) | 0.625 |

| Air and sun on the chest | 5 (7.2) | 9 (11.7) | 0.363 |

| Variable | Control Group (n = 65); n (%); Mean ± SD | Intervention Group (n = 71); n (%); mean ± SD | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age (weeks) | 39.4 ± 1.3 | 39.5 ± 1.1 | 0.618 |

| Vaginal birth | 48 (73.8) | 56 (80.0) | 0.396 |

| Breastfeeding start (hours) | 1.6 ± 5.0 | 1.7 ± 4.8 | 0.966 |

| Easy latch to the chest | 48 (73.8) | 55 (78.6) | 0.519 |

| Need for help | 31 (47.7) | 29 (37.7) | 0.464 |

| Goldberg Depression (post) | 2.2 ± 2.1 | 1.7 ± 2.1 | 0.175 |

| Goldberg Anxiety (post) | 2.9 ± 2.5 | 2.7 ± 2.1 | 0.533 |

| EQ5D mobility (post) | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.254 |

| EQ5D personal care (post) | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.820 |

| EQ5D activities of daily living (post) | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.319 |

| EQ5D pain/discomfort (post) | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 0.307 |

| EQ5D anxiety/depression (post) | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 0.832 |

| Self-perception of health status (post) | 77.8 ± 15.1 | 80.6 ± 18.6 | 0.354 |

| Postpartum discomfort | 43 (66.2) | 50 (71.4) | 0.508 |

| Variable | Control Group n/Nt (%) | Intervention Group n/Nt (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

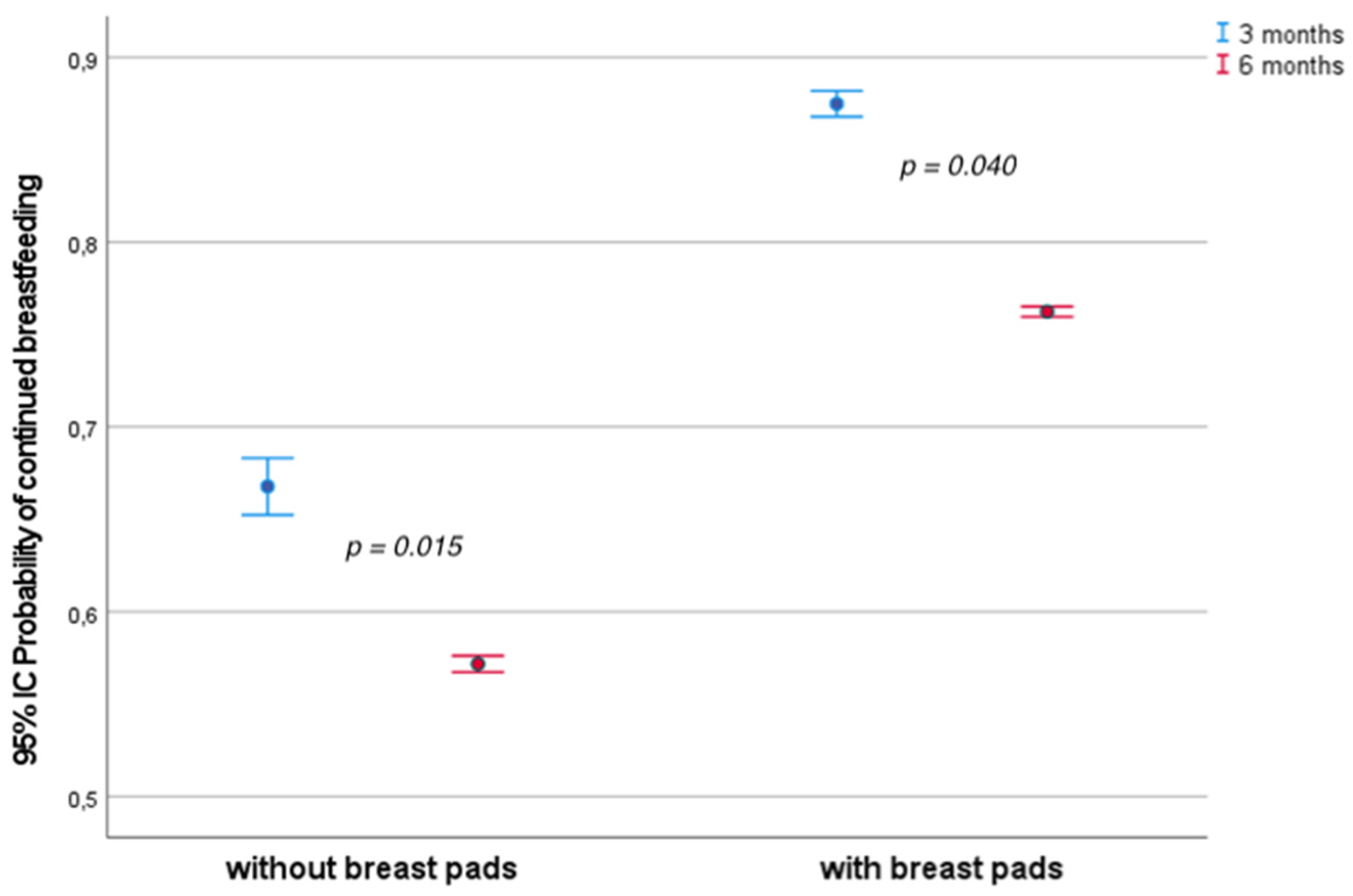

| Continued breastfeeding at 3 months | 42/62 (66.7) | 57/64 (87.7) | 0.004 |

| Continued breastfeeding at 6 months | 36/63 (57.1) | 45/59 (76.3) | 0.025 |

| Breastfeeding at 3 Months * | Breastfeeding at 6 Months ** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Adjusted OR 95% CI | p-Value | Adjusted OR 95% CI | p-Value |

| Type of delivery (vaginal vs. cesarean) | 0.561 (0.211–1.490) | 0.246 | 0.814 (0.324–2.045) | 0.662 |

| Use of breast pads | 3.129 (1.249–7.839) | 0.015 | 2.282 (1.038–5.016) | 0.040 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pastor-Pagés, I.; Ausina-Marquez, V.; Rizo-Baeza, M.M.; Cortés-Castell, E.; Noreña-Peña, A. Ecological Beeswax Breast Pads Promote Breastfeeding in First-Time Mothers from the Valencian Community (Spain): A Randomized Trial. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1330. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111330

Pastor-Pagés I, Ausina-Marquez V, Rizo-Baeza MM, Cortés-Castell E, Noreña-Peña A. Ecological Beeswax Breast Pads Promote Breastfeeding in First-Time Mothers from the Valencian Community (Spain): A Randomized Trial. Healthcare. 2025; 13(11):1330. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111330

Chicago/Turabian StylePastor-Pagés, Irene, Verónica Ausina-Marquez, María Mercedes Rizo-Baeza, Ernesto Cortés-Castell, and Ana Noreña-Peña. 2025. "Ecological Beeswax Breast Pads Promote Breastfeeding in First-Time Mothers from the Valencian Community (Spain): A Randomized Trial" Healthcare 13, no. 11: 1330. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111330

APA StylePastor-Pagés, I., Ausina-Marquez, V., Rizo-Baeza, M. M., Cortés-Castell, E., & Noreña-Peña, A. (2025). Ecological Beeswax Breast Pads Promote Breastfeeding in First-Time Mothers from the Valencian Community (Spain): A Randomized Trial. Healthcare, 13(11), 1330. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111330