Expert Guidelines on the Use of Cariprazine in Bipolar I Disorder: Consensus from Southeast Asia

Abstract

1. Introduction

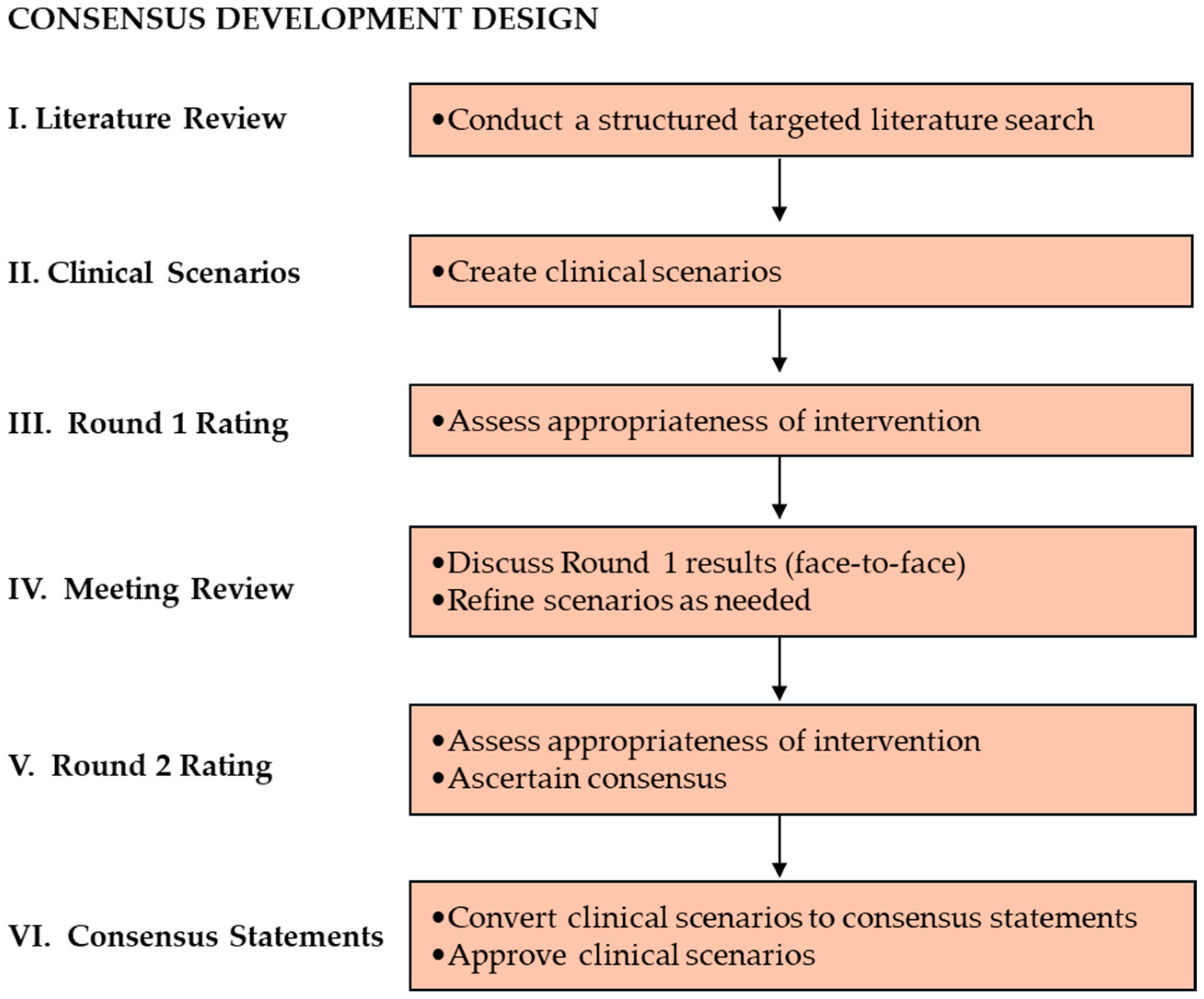

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Targeted Literature Review

2.2. Clinical Scenarios

2.3. First Round of Rating

2.4. Meeting Review

2.5. Second Round of Rating

2.6. Consensus Recommendations

3. Results

3.1. Bipolar 1 Disorder: Impact, Problems, and Challenges

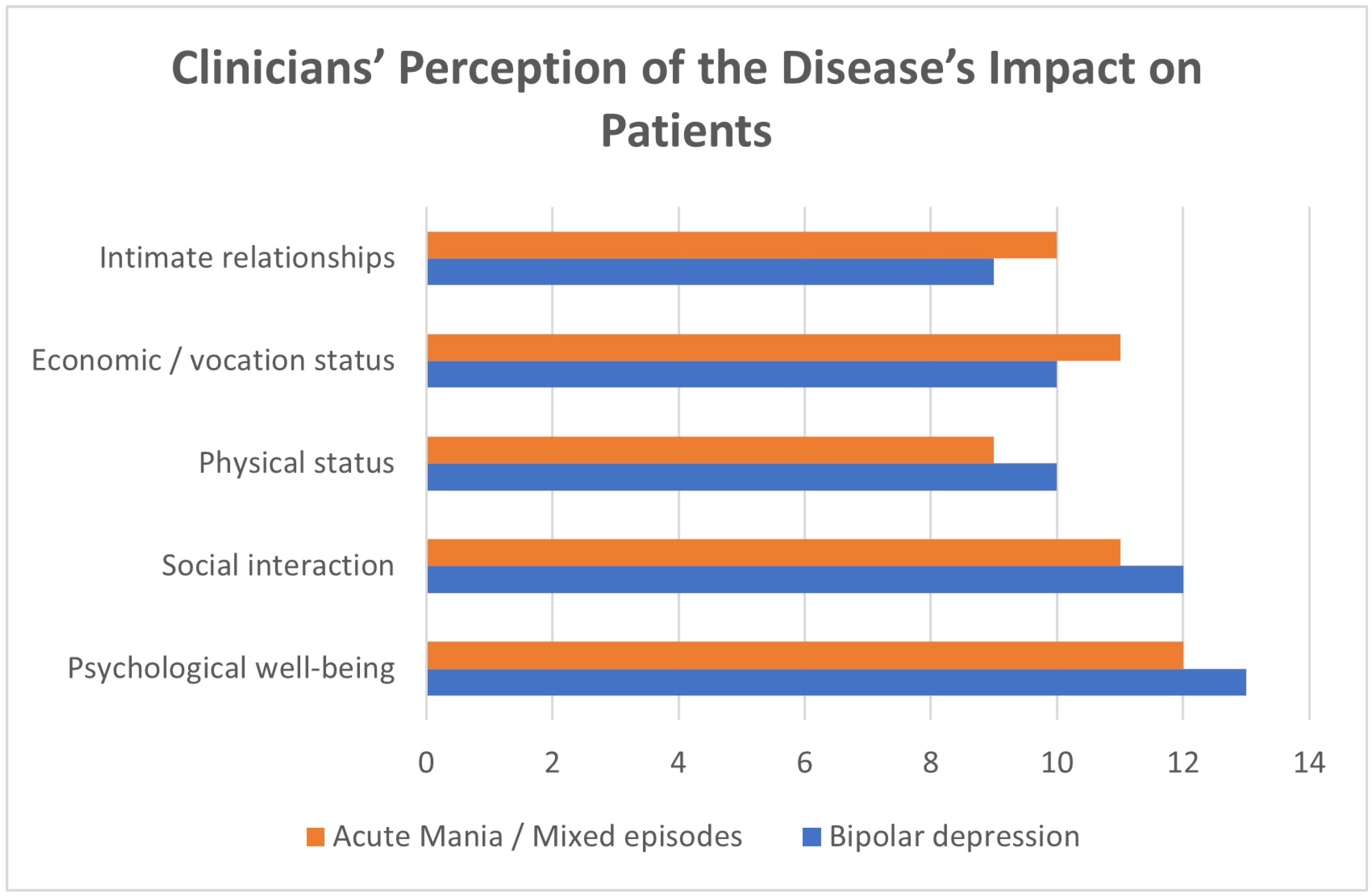

3.1.1. Clinicians’ Perception of the Disease’s Impact on Patients

3.1.2. Challenges in Screening and Diagnosis of BP1D

- Resources. The high patient load paired with inadequate human resource compounds the limited time of consultation. Added human resources that can mitigate time constraints in questionnaire administration are also limited.

- Psychiatric history. Incomplete history taking may lead to missed detection of subthreshold symptoms, manic episodes, and mixed features, as gathering of longitudinal data is necessary to identify the polarity index.

- Patient reliability. Patients may have an inclination to omit hypomanic states in their histories as they are often productive during these phases. Illness denial also contributes to delayed clinical consult.

- Rating scales. Screening tools, questionnaires and rating scales are often underutilized due to practicality issues. The possibility of rating scales not capturing the overall picture of a patient’s mood, such as the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) that may overlook bipolar 1 depression, risks misdiagnosis and outweighs any benefit to their use.

- Differential diagnoses. The differentiation of affective disorders with psychotic features from primary psychotic or thought disorders are also a notable diagnostic challenge. Challenges in assessment also include differentiation of bipolar disorder from unipolar depression (i.e., major depressive disorder with mixed features) and substance-induced mood disorder, as well as differentiation of bipolar 1 from bipolar 2 disorder.

- Comorbidities. The presence of personality disorders (e.g., borderline personality disorder) or a history of trauma with or without stress/trauma-related disorders can complicate assessment. The clinical presentation of bipolar disorder also tends to be atypical when substance use disorder is present.

3.1.3. Challenges in Management of BP1D

- Treatment adherence. Poor insight into their condition and denial of their illness often lead to poor adherence or engagement, and sometimes outright refusal, to the treatment plan.

- Pharmacologic management. Prompt medication effectiveness in instances where rapid response is needed while preventing development of contrapolar symptoms is a prominent concern. Clinicians may have difficulty choosing appropriate medication for their patients. Polypharmacy tends to prevail in symptom management. Tolerability issues including treatment-related adverse effects also affect patients’ treatment adherence.

- Healthcare system resources. With a limited number of psychotherapists across countries, some rely solely on pharmacotherapy-based treatments if psychotherapy services are not available. Problems with access to affordable medications and safety monitoring measures, as well as a shortage of suitable inpatient facilities are also concerns in the region.

3.2. General Recommendations on Best Practices for Screening, Diagnosis and Management of BP1D

3.3. Consensus Statements on Cariprazine’s Place in Therapy: Patient Characteristics to Consider

3.4. Cariprazine Dose Recommendations

Bipolar Depression

3.5. Treatment Duration

3.5.1. Bipolar Depression

3.5.2. Acute Mania/Mixed Episodes

3.6. Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events (TEAEs): Practical Recommendations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| α1/α2 | Alpha 1/Alpha 2 |

| 5HT1A | 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 1A |

| BP-1D | Bipolar 1 Disorder |

| CANMAT | Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments |

| CPG | Clinical Practice Guidelines |

| D2/D3 | Dopamine D2/Dopamine D3 |

| FAST | Reisberg Functional Assessment Screening Tool |

| GABA | Gamma-aminobutyric acid, γ-aminobutyric acid |

| HAM-A | Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| ISBD | International Society for Bipolar Disorders |

| MADRS | Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale |

| PANSS | Positive Scale, Negative Scale, and General Psychopathology Scale |

| RAM | RAND/UCLA Method |

| RAND/UCLA | RAND Corporation/University of California Los Angeles |

| RCBD | Rapid cycling bipolar disorders |

| TEAE | Treatment emergent adverse events |

| TLR | Targeted literature review |

References

- McIntyre, R.S.; Berk, M.; Brietzke, E.; Goldstein, B.I.; López-Jaramillo, C.; Kessing, L.V.; Malhi, G.S.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Majeed, A. Bipolar disorders. Lancet 2020, 396, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, V.; Fico, G.; De Prisco, M.; Gonda, X.; Rosa, A.R.; Vieta, E. Bipolar disorders: An update on critical aspects. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2025, 48, 101135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, K.; Sarkar, S.; Kattimani, S. Bipolar disorder in Asia: Illness course and contributing factors. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2017, 29, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teh, W.L.; Abdin, E.; Vaingankar, J.; Shafie, S.; Yiang Chua, B.; Sambasivam, R.; Zhang, Y.; Shahwan, S.; Chang, S.; Mok, Y.M.; et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorders in Singapore: Results from the 2016 Singapore Mental Health Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Mansur, R.; McIntyre, R.S. Mixed Specifier for Bipolar Mania and Depression: Highlights of DSM-5 Changes and Implications for Diagnosis and Treatment in Primary Care. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014, 16, PCC.13r01599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.L.; Zhu, J.F.; Shen, D.; Gao, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Jin, H.; Jin, W. New concept, definition and clinic of mixed unit in bipolar disorder. Arch. Psychiatry 2024, 2, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, D.; Reinares, M.; Goikolea, J.M.; Bonnin, C.M.; Gonzalez-Pinto, A.; Vieta, E. Polarity index of pharmacological agents used for maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012, 22, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natale, A.; Mineo, L.; Fusar-Poli, L.; Aguglia, A.; Rodolico, A.; Tusconi, M.; Amerio, A.; Serafini, G.; Amore, M.; Aguglia, E. Mixed depression: A mini-review to guide clinical practice and future research developments. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadock, B.J.; Sadock, V.A.; Ruiz, P. Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry, 12th ed.; Wolters Kluwer Health: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hett, D.; Morales-Muñoz, I.; Durdurak, B.B.; Carlish, M.; Marwaha, S. Rates and associations of relapse over 5 years of 2649 people with bipolar disorder: A retrospective UK cohort study. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2023, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abé, C.; Ching, C.R.K.; Liberg, B.; Lebedev, A.V.; Agartz, I.; Akudjedu, T.N.; Alda, M.; Alnæs, D.; Alonso-Lana, S.; Benedetti, F.; et al. Longitudinal structural brain changes in bipolar disorder: A multicenter neuroimaging study of 1232 individuals by the ENIGMA Bipolar Disorder Working Group. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 91, 708–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, S.M. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Applications, 5th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Malhi, G.S.; Bell, E.; Bassett, D.; Boyce, P.; Bryant, R.; Hazell, P.; Hopwood, M.; Lyndon, B.; Mulder, R.; Porter, R.; et al. The 2020, Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2021, 55, 7–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keramatian, K.; Chithra, N.K.; Yatham, L.N. The CANMAT and ISBD guidelines for the treatment of bipolar disorder: Summary and a 2023 update of evidence. Focus (Am. Psychiatr. Publ.) 2023, 21, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citrome, L. Cariprazine for bipolar depression: What is the number needed to treat, number needed to harm and likelihood to be helped or harmed? Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2019, 73, e13397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, A.; Keramatian, K.; Schaffer, A.; Yatham, L. Cariprazine in the treatment of bipolar disorder: Within and beyond clinical trials. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 769897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.; Aggarwal, R.; Khanna, D. Methods of formal consensus in classification/diagnostic criteria and guideline development. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 41, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tor, P.C.; Amir, N.; Fam, J.; Ho, R.; Ittasakul, P.; Maramis, M.M.; Ponio, B.; Purnama, D.A.; Rattanasumawong, W.; Rondain, E.; et al. A Southeast Asia Consensus on the Definition and Management of Treatment-Resistant Depression. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2022, 18, 2747–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, K.Y.; Muhdi, N.; Ali, N.H.; Amir, N.; Bernardo, C.; Chan, L.F.; Ho, R.; Ittasakul, P.; Kwansanit, P.; Mariano, M.P.; et al. A Southeast Asian expert consensus on the management of major depressive disorder with suicidal behavior in adults under 65 years of age. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destouches, S.; Molière, F.; Richieri, R.; Bougerol, T.; Charpeaud, T.; Genty, J.-B.; Dorey, J.; El-Hage, W.; Camus, V.; Doumy, O.; et al. Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Treatment-Resistant Depression: French Recommendations from Experts, the French Association for Biological Psychiatry and Neuropsychopharmacology and the Fondation FondaMental. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 262. [Google Scholar]

- Mangat, G.; Sharma, S. MSR36 How Does the Use of Different Targeted Literature Review (TLR) Methodologies Impact the Research Output? A Case Study of Structured vs. Focused Vs. Pearl Growing Approach. Value Health 2023, 26, S284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; Lalu, M.; Glanville, J.; Tricco, A.; Stewart, L.; Brennan, S.; Shamseer, L.; Thomas, J.; Bossuyt, P.; et al. The PRISMA 2020, Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372 (Suppl. 1), n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketter, T.A. Monotherapy versus combined treatment with second-generation antipsychotics in bipolar disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008, 69, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragguett, R.M.; McIntyre, R.S. Cariprazine for the treatment of bipolar depression: A review. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2024, 19, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gesi, C.; Paletta, S.; Palazzo, M.C.; Dell’Osso, B.; Mencacci, C.; Cerveri, G. Cariprazine in three special different areas: A real-world experience. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021, 17, 3581–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, L.L.; Schettler, P.J.; Akiskal, H.S.; Coryell, W.; Leon, A.C.; Maser, J.D.; Solomon, D.A. Residual symptom recovery from major affective episodes in bipolar disorders and rapid episode relapse/recurrence. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2008, 65, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrabie, M.; Marinescu, V.; Talaşman, A.; Tăutu, O.; Drima, E.; Micluţia, I. Cognitive impairment in manic bipolar patients: Important, understated, significant aspects. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry. 2015, 14, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Daniel, D.G.; Vieta, E.; Laszlovszky, I.; Goetghebeur, P.J.; Earley, W.R.; Patel, M.D. The efficacy of cariprazine on cognition: A post hoc analysis from phase II/III clinical trials in bipolar mania, bipolar depression, and schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2023, 28, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; McIntyre, R.S.; Cutler, A.J.; Earley, W.R.; Nguyen, H.B.; Adams, J.L.; Yatham, L.N. Efficacy of cariprazine in patients with bipolar depression and higher or lower levels of baseline anxiety: A pooled post hoc analysis. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2024, 39, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroff, S.N.; Ungvari, G.S.; Gazdag, G. Treatment of schizophrenia with catatonic symptoms: A narrative review. Schizophr. Res. 2024, 263, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.S. Cariprazine in an adolescent with Tourette syndrome with comorbid attention deficit hyperactive disorder and depression: A case report. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csehi, R.; Dombi, Z.B.; Sebe, B.; Molnár, M.J. Real-life clinical experience with cariprazine: A systematic review of case studies. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 827744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Sol Calderon, P.; Izquierdo de la Puente, A.; Fernández Fernández, R.; García Moreno, M. Use of cariprazine as an impulsivity regulator in an adolescent with non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal attempts: Case report. Eur. Psychiatry 2023, 66, S739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Quiroga, A.; Alvarez-Mon, M.A.; Mora, F.; Quintero, J. Cariprazine as an anti-impulsive treatment in a case series of patients with HIV and chemsex practices. J. Clin. Images Med. Case Rep. 2022, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusaroli, M.; Raschi, E.; Giunchi, V.; Menchetti, M.; Rimondini Giorgini, R.; De Ponti, F.; Poluzzi, E. Impulse control disorders by dopamine partial agonists: A pharmacovigilance-pharmacodynamic assessment through the FDA adverse event reporting system. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022, 25, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazu, L.; Morera-Herreras, T.; Garcia, M.; Aguirre, C.; Lertxundi, U. Do cariprazine and brexpiprazole cause impulse control symptoms? A case/non-case study. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021, 50, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, D.; Patrick, C.J.; Kennealy, P.J. Role of serotonin and dopamine system interactions in the neurobiology of impulsive aggression and its comorbidity with other clinical disorders. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2008, 13, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseligkaridou, G.; Egger, S.T.; Spiller, T.R.; Schneller, L.; Frauenfelder, F.; Vetter, S.; Seifritz, E.; Burrer, A. Relationship between antipsychotic medication and aggressive events in patients with a psychotic disorder hospitalized for treatment. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatham, L.N.; Chakrabarty, T.; Bond, D.J.; Schaffer, A.; Beaulieu, S.; Parikh, S.V.; McIntyre, R.S.; Milev, R.V.; Alda, M.; Vazquez, G.; et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) recommendations for the management of patients with bipolar disorder with mixed presentations. Bipolar Disord. 2021, 23, 767–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indications | Rating | Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| For an adult patient diagnosed with bipolar 1 depression, | |||

| 1 | … cariprazine monotherapy is preferred in most cases | Appropriate | 8 (8–9) |

| 2 | … cariprazine combination therapy with other mood stabilizers (e.g., lithium, divalproex) is suitable in certain scenarios. | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| 3 | … cariprazine is suitable as a first-line treatment. | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| 4 | … cariprazine is suitable in first episode bipolar 1 depression. | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| For an adult patient diagnosed with bipolar 1 depression, cariprazine is suitable for patients with: | |||

| 5 | … suicidal ideation or behavior | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| 6 | … cognitive symptoms (e.g., problems with concentration, mental calculation, solving problems, learning new information) | Appropriate | 9 (8–9) |

| 7 | … functional impairment | Appropriate | 8 (8–9) |

| 8 | … partial adherence or non-adherence to previous medications | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| 9 | … older age (>65 years old) | Appropriate | 8 (6–9) |

| 10 | … anhedonia | Appropriate | 8 (6–9) |

| For an adult patient diagnosed with bipolar 1 depression, cariprazine is suitable for patients with the following clinical features: | |||

| 11 | … need for rapid response is required, e.g., patients at risk of suicide, with psychotic features, or who have medical complications, including dehydration | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| 12 | … anxious distress | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| 13 | … mixed features | Appropriate | 8 (8–9) |

| 14 | … rapid cycling | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| 15 | … psychotic features | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| 16 | … melancholia features | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| 17 | … atypical features | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| 18 | … postpartum onset (without breastfeeding) | Appropriate | 8 (6–9) |

| 19 | … catatonia | Appropriate | 7 (2–9) |

| For an adult patient diagnosed with bipolar 1 depression, cariprazine is suitable for patients with the following co-morbidities: | |||

| 20 | … substance use disorder | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| 21 | … impulse control disorders | Appropriate | 8 (6–9) |

| 22 | … anxiety disorders | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| 23 | … obsessive compulsive disorder | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| 24 | …. ADHD | Appropriate | 7 (5–9) |

| 25 | … personality disorders | Appropriate | 8 (6–9) |

| 26 | … metabolic disorders | Appropriate | 7 (7–9) |

| Indications | Rating | Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| For an adult patient diagnosed with bipolar 1 disorder in an acute mania/mixed episode, | |||

| 1 | … cariprazine monotherapy is preferred in most cases. | Appropriate | 8 (8–9) |

| 2 | … cariprazine combination therapy with other mood stabilizers (e.g., lithium, divalproex) is suitable in certain scenarios. | Appropriate | 8 (8–9) |

| 3 | … cariprazine is suitable as a first-line treatment. | Appropriate | 8 (8–9) |

| 4 | … cariprazine is suitable in first episode mania. | Appropriate | 8 (8–9) |

| For an adult patient diagnosed with bipolar 1 disorder in an acute mania/mixed episode, cariprazine is suitable for patients with: | |||

| 5 | … suicidal ideation or behavior | Appropriate | 8 (8–9) |

| 6 | … agitation as monotherapy | Appropriate | 8 (8–9) |

| 7 | … agitation in combination with benzodiazepine | Appropriate | 9 (8–9) |

| 8 | … cognitive symptoms (e.g., problems with concentration, mental calculation, solving problems, learning new information) | Appropriate | 9 (8–9) |

| 9 | … functional impairment | Appropriate | 8 (8–9) |

| 10 | … partial adherence or non-adherence to previous medications | Appropriate | 8 (8–9) |

| 11 | … older age (>65 years old) | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| 12 | … anhedonia | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| For an adult patient diagnosed with bipolar 1 disorder in an acute mania/mixed episode, cariprazine is suitable for patients with the following clinical features: | |||

| 13 | … need for rapid response is required, e.g., patients at risk of suicide, with psychotic features, or who have medical complications, including dehydration. | Appropriate | 8 (8–9) |

| 14 | … anxious distress | Appropriate | 8 (8–9) |

| 15 | … mixed features | Appropriate | 8 (8–9) |

| 16 | … concurrent depressive symptoms | Appropriate | 8 (8–9) |

| 17 | … rapid cycling | Appropriate | 8 (8–9) |

| 18 | … psychotic features | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| 19 | … hostility | Appropriate | 8 (8–9) |

| 20 | … irritability/disruptive-aggressive behavior | Appropriate | 8 (8–9) |

| 21 | … catatonia | Appropriate | 8 (8–9) |

| 22 | … postpartum onset (without breastfeeding) | Appropriate | 8 (7–8) |

| For an adult patient diagnosed with bipolar 1 disorder in an acute mania/mixed episode, cariprazine is suitable for patients with the following co-morbidities: | |||

| 23 | … substance use disorder | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| 24 | … impulse control disorders | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| 25 | … anxiety disorders | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| 26 | … obsessive compulsive disorder | Appropriate | 8 (7–9) |

| 27 | …. ADHD | Appropriate | 8 (7–8) |

| 28 | … personality disorders | Appropriate | 7 (6–8) |

| 29 | … metabolic disorders | Appropriate | 8 (7–8) |

| Suggestions for Lower Dose | Suggestions for Higher Dose |

|

|

| Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events Associated with Cariprazine | Current Practices |

| Tardive Syndromes | |

| Tardive syndromes, i.e., akathisia, parkinsonism, dystonic reactions |

|

| Sleep Disturbances | |

| Insomnia |

|

| Somnolence/sedation |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sulaiman, A.H.; Amin, M.M.; Ang, J.K.; Ho, R.; Nik Jaafar, N.R.; Ng, C.G.; Wibowo Nurhidayat, A.; Paholpak, P.; Pariwatcharakul, P.; Sanguanvichaikul, T.; et al. Expert Guidelines on the Use of Cariprazine in Bipolar I Disorder: Consensus from Southeast Asia. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111304

Sulaiman AH, Amin MM, Ang JK, Ho R, Nik Jaafar NR, Ng CG, Wibowo Nurhidayat A, Paholpak P, Pariwatcharakul P, Sanguanvichaikul T, et al. Expert Guidelines on the Use of Cariprazine in Bipolar I Disorder: Consensus from Southeast Asia. Healthcare. 2025; 13(11):1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111304

Chicago/Turabian StyleSulaiman, Ahmad Hatim, Mustafa M. Amin, Jin Kiat Ang, Roger Ho, Nik Ruzyanei Nik Jaafar, Chong Guan Ng, Adhi Wibowo Nurhidayat, Pongsatorn Paholpak, Pornjira Pariwatcharakul, Thitima Sanguanvichaikul, and et al. 2025. "Expert Guidelines on the Use of Cariprazine in Bipolar I Disorder: Consensus from Southeast Asia" Healthcare 13, no. 11: 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111304

APA StyleSulaiman, A. H., Amin, M. M., Ang, J. K., Ho, R., Nik Jaafar, N. R., Ng, C. G., Wibowo Nurhidayat, A., Paholpak, P., Pariwatcharakul, P., Sanguanvichaikul, T., Ung, E. K., Wardani, N. D., & Yeo, B. (2025). Expert Guidelines on the Use of Cariprazine in Bipolar I Disorder: Consensus from Southeast Asia. Healthcare, 13(11), 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111304