Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors of Geographic Tongue: A Retrospective Analysis of 100 Polish Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

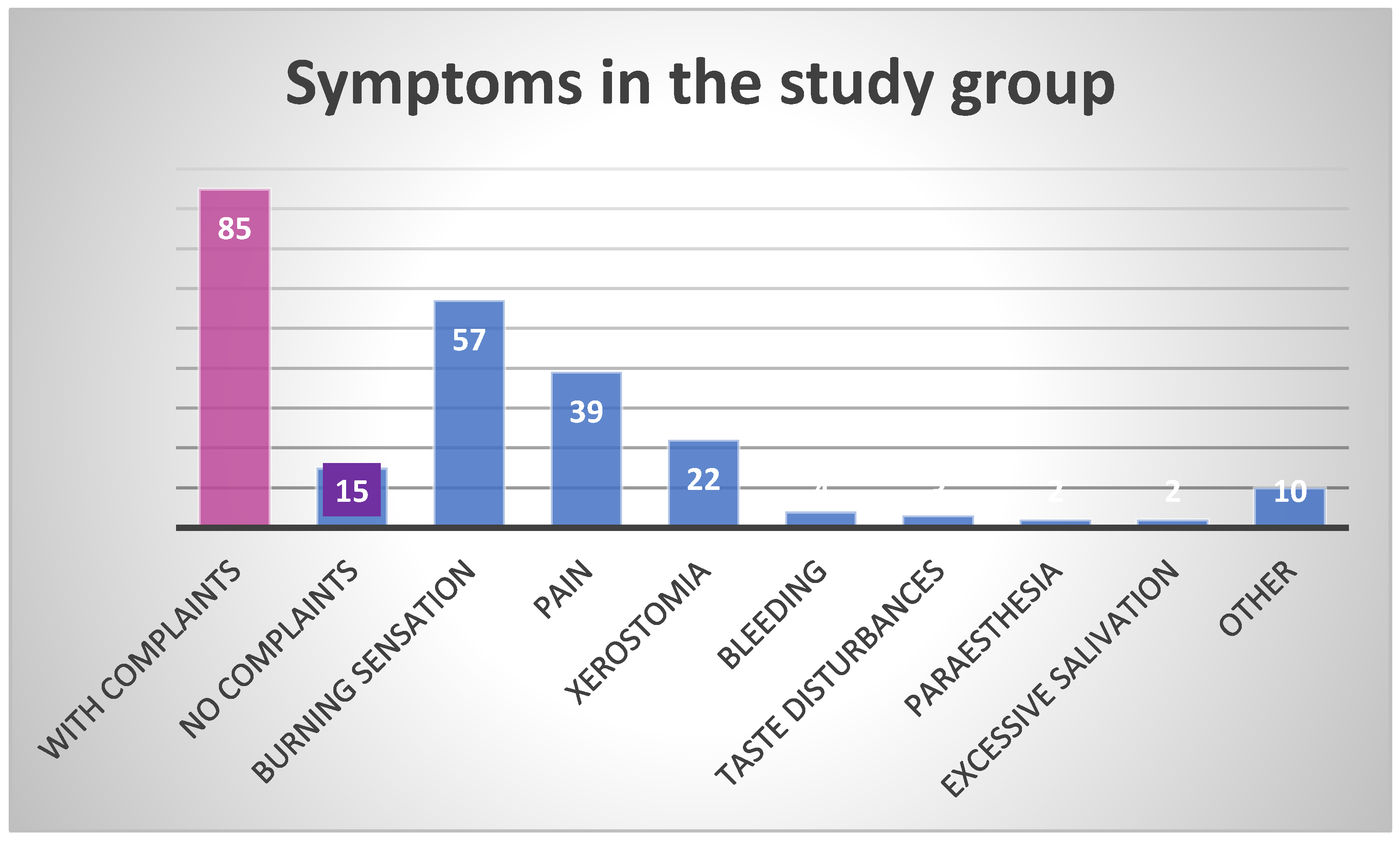

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations of This Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Netto, J.N.S.; Dias, M.C.; Garcia, T.R.U.; Amaral, S.M.; Miranda, Á.M.M.A.; Pires, F.R. Geographic stomatitis: An enigmatic condition with multiple clinical presentations. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2019, 11, e845–e849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assimakopoulos, D.; Patrikakos, G.; Fotika, C. Benign migratory glossitis or geographic tongue: An enigmatic oral lesion. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2002, 23, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogueta, C.I.; Ramírez, P.M.; Jiménez, O.C.; Cifuentes, M.M. Geographic Tongue: What a Dermatologist Should Know. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019, 110, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi, Y. Geographic tongue: What is this disease? J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2023, 21, 1465–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, B.E. Erythema migrans affecting the oral mucosa. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. 1955, 8, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hume, W.J. Geographic stomatitis: A critical review. J. Dent. 1975, 3, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picciani, B.L.; Domingos, T.A.; Teixeira-Souza, T.; Santos Vde, C.; Gonzaga, H.F.; Cardoso-Oliveira, J.; Gripp, A.C.; Dias, E.P.; Carneiro, S. Geographic tongue and psoriasis: Clinical, histopathological, immunohistochemical and genetic correlation—A literature review. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2016, 91, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullaa-Mikkonen, A.; Koskela, R.; Teppo, H. A clinical study of the association of geographic and fissured tongue with atopy. Clin. Allergy 1988, 18, 569–576. [Google Scholar]

- Banoczy, J.; Csiba, A. Migratory glossitis: A clinical histopathologic study. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. 1975, 39, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, R.; Simons, M.J. Geographic tongue—A manifestation of atopy. Br. J. Dermatol. 1979, 101, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novianti, Y.; Nur’aeny, N. Identifying Chili as a Risk Factor for the Geographic Tongue: A Case Report. J. Asthma Allergy 2023, 16, 1279–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dafar, A.; Bankvall, M.; Çevik-Aras, H.; Jontell, M.; Sjöberg, F. Lingual microbiota profiles of patients with geographic tongue. J. Oral. Microbiol. 2017, 9, 1355206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandini, D.B.; Bhavana, S.B.; Deepak, B.S.; Ashwini, R. Paediatric Geographic Tongue: A Case Report, Review and Recent Updates. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016, 10, ZE05-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jainkittivong, A.; Lanlais, R.P. Geographic tongue: Clinical characteristics of 188 cases. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2005, 1, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwazeh, A.M.G.; Almelaih, A.A. Tongue lesions in a Jordanian population. Prevalence, symptoms, subject’s knowledge and treatment provided. Med. Oral. Patol. Oral. Cir. Bucal 2011, 16, e745–e749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, Y.; Yan, W.; Zhou, Y. Association of psoriasis with geographic and fissured tongue in the Han population in southwestern China. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2024, 99, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.D.P.L.; de Oliveira, J.M.D.; Pauletto, P.; Munhoz, E.A.; Silva Guerra, E.N.; Massignan, C.; De Luca Canto, G. Worldwide prevalence of geographic tongue in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral. Dis. 2023, 29, 3091–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çağlayan, F.; Demir, S.; Tosun, Z.T.; Laloğlu, A. A cross-sectional study of tongue disorders among dental outpatients. J. Stomatol. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 126, 102118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasem, S.F.; Ashkanani, H.; Ali, A. Therapeutic Advancements in the Management of Psoriasis: A Clinical Overview and Update. Cureus 2025, 17, e79097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Álvarez, L.; García-Martín, J.M.; García-Pola, M.J. Association between geographic tongue and psoriasis: A systematic review and meta-analyses. J. Oral. Pathol. Med. 2019, 48, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łuszczek, W.; Mańczak, M.; Cisło, M.; Nockowski, P.; Wiśniewski, A.; Jasek, M.; Kuśnierczyk, P. Gene for the activating natural killer cell receptor, KIR2DS1, is associated with susceptibility to psoriasis vulgaris. Hum. Immunol. 2004, 65, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Berki, D.M.; Choon, S.E.; Burden, A.D.; Allen, M.A.; Andrew, D.; Smith, C.H. IL36RN mutations in geographic tongue and generalized pustular psoriasis. Hum. Genet. 2016, 135, 569–573. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzaga, H.F.; Torres, E.A.; Alchorne, M.M.; Gerbase-Delima, M. Both psoriasis and benign migratory glossitis are associated with HLA-Cw6. Br. J. Dermatol. 1996, 135, 368–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudko, A.; Kurnatowska, A.J.; Kurnatowski, P. Prevalence of fungi in cases of geographical and fissured tongue. Ann. Parasitol. 2013, 59, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marks, R.; Tait, B. HLA antigens in geographic tongue. TSANA2 1980, 15, 6–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Huang, P.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Ni, C.; Wang, Y.; Shen, J.; Li, C.; Kang, L.; Chen, J.; et al. Mutations in IL36RN are associated with geographic tongue. Hum. Genet. 2017, 136, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- İpek, R.; Akalın, A.; Habiloğlu, E.; Hattapoğlu, S.; Pirinççioğlu, A.G. The fourth family in the world with a novel variant in the ATP5MK gene: Four siblings with complex V (ATP synthase) deficiency. Neurogenetics 2025, 26, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, R.G.; Cano, A.; Ortiz, A.; Espina, M.; Prat, J.; Muñoz, M.; Severino, P.; Souto, E.B.; García, M.L.; Pujol, M.; et al. Psoriasis: From Pathogenesis to Pharmacological and Nano-Technological-Based Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picciani, B.L.S.; Domingos, T.A.; Teixeira-Souza, T.; Fausto-Silva, A.K.; Dias, E.P.; Carneiro, S. Evaluation of the Th17 pathway in psoriasis and geographic tongue. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2019, 94, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafar, A.; Bankvall, M.; Garsjö, V.; Jontell, M.; Çevik-Aras, H. Salivary levels of interleukin-8 and growth factors are modulated in patients with geographic tongue. Oral. Dis. 2017, 23, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, R.S. Nutritional deficiencies and geographic tongue. J. Chronic Dis. 1964, 17, 627–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honarmand, M.; Farhad Mollashahi, L.; Shirzaiy, M.; Sehhatpour, M. Geographic Tongue and Associated Risk Factors among Iranian Dental Patients. Iran. J. Public. Health 2013, 42, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cigic, L.; Galic, T.; Kero, D.; Simunic, M.; Medvedec Mikic, I.; Kalibovic Govorko, D.; Biocina Lukenda, D. The Prevalence of celiac disease in patients with geographic tongue. J. Oral. Pathol. Med. 2016, 45, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dafar, A.; Çevik-Aras, H.; Robledo-Sierra, J.; Mattsson, U.; Jontell, M. Factors associated with geographic tongue and fissured tongue. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2016, 74, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubiche, T.; Valenza, B.; Chevreau, C.; Fricain, J.C.; Del Giudice, P.; Sibaud, V. Geographic tongue induced by angiogenesis inhibitors. Oncologist 2013, 18, e16–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Garcia, M.; Roman-Sainz, J.; Silvestre-Torner, N.; Tabbara Carrascosa, S. Bevacizumab-Induced Geographic Tongue. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2021, 11, e2021043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, S.; Burge, F. Geographical tongue induced by axitinib. BMJ Case Rep. 2015, 2015, bcr2015211318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, A.; Lodolo, M.; Sonis, S. Oral mucosal toxicities in oncology. Expert. Opin. 2025, 26, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullaa-Mikkonen, A.; Kotilainen, R. The Prevalence of oral carriers of Candida in patients with tongue abnormalities. J. Dent. 1983, 11, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanth, V.J.; Singh, A. Geographic tongue. CMAJ 2021, 193, E1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaubal, T.; Bapat, R. Geographic Tongue. Am. J. Med. 2017, 130, e533–e534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dick, T.N.A.; Santos, L.R.; Gonçalves, K.S.; Silva-Junior, G.O.; Dziedzic, A.; Aredes, M.M.; Junior, A.S.; Gonzaga, H.F.; Dias, E.P.; Picciani, B.L.S. Study of the Correlation between the Extent and Clinical Severity, and the Histopathological Characteristics of Geographic Tongue. Folia Morphol 2024. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.M.; Silva, D.R.; Caldas, A.L. Geographic tongue: A review of the literature with a focus on the treatment approaches. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2020, 95, 628–634. [Google Scholar]

- Diniz-Freitas, M.; García-García, A. Geographic tongue and oral cancer: A study of 8 cases. J. Oral. Pathol. Med. 2005, 34, 562–566. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Nivash, S.; Mann, B.K. Matched case-control study to examine association of psoriasis and migratory glossitis in India. Indian. J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2013, 79, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Álvarez, L.; García-Pola, M.J.; Garcia-Martin, J.M. Geographic tongue: Predisposing factors, diagnosis and treatment. A systematic review. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2018, 218, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomb, R.; Hajj, H.; Nehme, E. Manifestations buccales du psoriasis [Oral lesions in psoriasis]. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 2010, 137, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picciani, B.L.; Souza, T.T.; Santos Vde, C.; Domingos, T.A.; Carneiro, S.; Avelleira, J.C.; Azulay, D.R.; Pinto, J.M.; Dias, E.P. Geographic tongue and fissured tongue in 348 patients with psoriasis: Correlation with disease severity. Sci. World J. 2015, 2015, 564326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaee, R.; Hajheydari, Z.; Moghaddam, A.Y.; Seyyed Alireza Moraveji, S.A.; Ravandi, B.F. Prevalence of Oral Mucosal Lesions and Their Association with Severity of Psoriasis among Psoriatic Patients Referred To Dermatology Clinic: A Cross-Sectional Study in Kashan/Iran. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 5, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olejnik, M.; Osmola-Mańkowska, A.; Ślebioda, Z.; Adamski, Z.; Dorocka-Bobkowska, B. Oral mucosal lesions in psoriatic patients based on disease severity and treatment approach. J. Oral. Pathol. Med. 2020, 49, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślebioda, Z.; Szponar, E.; Linke, K. Comparative analysis of the oral cavity status in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. J. Stomatol. 2011, 64, 3–4, 212–224. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Pan, D.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, T.; Zhou, Y. The risk factors associated with geographic tongue in a southwestern Chinese population. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. 2022, 134, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, J.; Shenkman, A.; Stavropoulos, F.; Melzer, E. Oral signs and symptoms in relation to disease activity and site of involvement in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Oral. Dis. 2003, 9, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garsjö, V.; Dafar, A.; Jontell, M.; Çevik-Aras, H.; Bratel, J. Increased levels of calprotectin in the saliva of patients with geographic tongue. Oral. Dis. 2020, 26, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majster, M.; Almer, S.; Bostr€om, E.A. Salivary calprotectin is elevated in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2019, 107, 104528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, L.J.; Baghdady, V.S. prevalence of geographic and plicated tongue in 6090 Iraqi school children. Community Dent. Oral. Epidemiol. 1982, 10, 214–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar-Odeh, N.S.; Hayajneh, W.A.; Abu-Hammad, O.A.; Hammad, H.M.; Al-Wahadneh, A.M.; Bulos, N.K.; Mahafzah, A.M.; Shomaf, M.S.; El-Maaytah, M.A.; Bakri, F.G. Orofacial findings in chronic granulomatous disease. Report of twelve patients and review of literature. BMC Res. Notes 2010, 3, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shulman, J.D.; Carpenter, W.M. Prevalence and risk factors associated with geographic tongue among US adults. Oral. Dis. 2006, 12, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miloglu, O.; Göregen, M.; Akgül, H.M.; Acemoglu, H. The prevalence and risk factors associated with benign migratory glossitis lesions in 7619 Turkish dental outpatients. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. Endod. 2009, 107, e29–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koay, C.L.; Lim, J.A.; Siar, C.H. The Prevalence of tongue lesions in Malaysian dental outpatients from the Klang Valley area. Oral. Dis. 2011, 17, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hume’s Classification | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Geographic tongue, without geographic lesions elsewhere in the mouth |

| 2 | Geographic tongue, accompanied by geographic lesions elsewhere in the mouth |

| 3 | Atypical, fixed, or abortive, tongue lesions, whether or not accompanied by geographic lesions elsewhere in the mouth |

| 4 | Geographic lesions elsewhere in the mouth without the presence of a geographic tongue |

| Netto et al.’s classification | |

| 1 | Geographic tongue |

| 2 | Geographic stomatitis without tongue involvement |

| 3 | Geographic stomatitis with geographic tongue |

| 4 | Geographic tongue associated with cutaneous diseases (i.e., psoriasis) |

| 5 | Geographic stomatitis without tongue involvement associated with cutaneous diseases (i.e., psoriasis) |

| 6 | Geographic stomatitis with geographic tongue associated with cutaneous diseases (i.e., psoriasis) |

| n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 100 (100%) | |

| Gender distribution | ||

| Females | 52 (52%) | 0.5716 |

| Males | 48 (48%) | |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | 19 (19%) | <0.0001 |

| Urban | 81 (81%) | |

| Habits | ||

| Smokers | 13 (13%) | <0.0001 |

| Non-smokers | 87 (87%) | |

| Total | Females | Males | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD, range [years]) | 51.6 ± 22.2 16–101 | 57.0 ± 20.8 16–101 | 46.0 ± 22.5 18–95 | 0.0126 |

| n, % of TSP * | F (n = 52) | M (n = 48) | p | <40 y.o. (n = 43) | >40 y.o. (n = 57) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients reporting complaints | 85 (85%) | 46 | 39 | 0.3167 | 34 | 51 | 0.0150 |

| Number of patients not reporting any complaints | 15 (15%) | 6 | 9 | 0.4206 | 9 | 6 | 0.4206 |

| Total number of complaints | 139 | 82 | 57 | 0.0029 | 52 | 87 | <0.0001 |

| Symptom | |||||||

| Burning sensation | 57 (57%) | 36 | 21 | 0.0188 | 22 | 35 | 0.0417 |

| Pain | 39 (39%) | 21 | 18 | 0.5924 | 17 | 22 | 0.3722 |

| Xerostomia | 22 (22%) | 12 | 10 | 0.6513 | 5 | 17 | 0.0067 |

| Bleeding | 4 (4%) | 1 | 3 | 0.3124 | 2 | 2 | 1.0000 |

| Taste disturbances | 3 (3%) | 3 | 0 | 0.0810 | 1 | 2 | 0.5607 |

| Paresthesia | 2 (2%) | 1 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1 | 1.0000 |

| Excessive saliva production | 2 (2%) | 1 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1 | 1.0000 |

| Other | 10 (10%) | 7 | 3 | 0.1944 | 3 | 7 | 0.1944 |

| Patient | Age | Sex | Systemic Comorbidities | Oral Comorbidities | Habits | Histopathologic Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 89 | F | HT | Denture-induced ulcer | NR | Inflammatory infiltrate without dysplasia |

| TJ | 71 | M | COPD, HT, cardiovascular disorders, prostatic hyperplasia | Lichen planus, oral melanotic macule | NR | Hyperkeratosis and lymphocytic infiltrate |

| Oral Condition | n = % of TSP * |

|---|---|

| Candidiasis | 13 |

| Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) | 10 |

| Fissured tongue (FT) | 6 |

| Linea alba | 6 |

| Lichen planus (LP) | 5 |

| Denture stomatitis | 3 |

| Trauma-induced ulcer | 3 |

| Gingivitis | 3 |

| Angioma | 3 |

| Cheilitis | 2 |

| Systemic Diseases | n (%) | F (n = 52) | M (n = 48) | p | <40 y.o. (n = 43) | >40 y.o. (n = 57) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease reported | 76 (76%) | 43 | 33 | 0.1452 | 24 | 52 | <0.0001 |

| Disease not reported | 24 (24%) | 9 | 15 | 0.1917 | 19 | 5 | 0.0023 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 37 (37%) | 20 | 17 | 0.5849 | 3 | 17 | 0.0047 |

| Gastrointestinal diseases | 24 (24%) | 16 | 8 | 0.0817 | 7 | 17 | 0.0296 |

| Thyroid disorders | 18 (18%) | 17 | 1 | 0.0001 | 8 | 10 | 0.6212 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 15 (14%) | 7 | 8 | 0.7883 | 1 | 6 | 0.0544 |

| Allergy | 13 (13%) | 6 | 7 | 0.7742 | 6 | 7 | 0.7742 |

| Asthma | 8 (8%) | 3 | 5 | 0.4705 | 3 | 5 | 0.4705 |

| Neurological diseases | 3 (3%) | 2 | 1 | 0.5607 | 1 | 2 | 0.5607 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 3 (3%) | 1 | 2 | 0.5607 | 0 | 3 | 0.0810 |

| Psoriasis | 1 (1%) | 1 | 0 | 0.3161 | 0 | 1 | 0.3161 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ślebioda, Z.; Drożdżyńska, J.; Karpińska, A.; Krzyżaniak, A.; Kasperczak, M.; Tomoń, N.; Wiśniewska, P.; Wyganowska, M.L. Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors of Geographic Tongue: A Retrospective Analysis of 100 Polish Patients. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1299. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111299

Ślebioda Z, Drożdżyńska J, Karpińska A, Krzyżaniak A, Kasperczak M, Tomoń N, Wiśniewska P, Wyganowska ML. Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors of Geographic Tongue: A Retrospective Analysis of 100 Polish Patients. Healthcare. 2025; 13(11):1299. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111299

Chicago/Turabian StyleŚlebioda, Zuzanna, Julia Drożdżyńska, Aleksandra Karpińska, Aleksandra Krzyżaniak, Marianna Kasperczak, Natalia Tomoń, Paulina Wiśniewska, and Marzena Liliana Wyganowska. 2025. "Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors of Geographic Tongue: A Retrospective Analysis of 100 Polish Patients" Healthcare 13, no. 11: 1299. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111299

APA StyleŚlebioda, Z., Drożdżyńska, J., Karpińska, A., Krzyżaniak, A., Kasperczak, M., Tomoń, N., Wiśniewska, P., & Wyganowska, M. L. (2025). Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors of Geographic Tongue: A Retrospective Analysis of 100 Polish Patients. Healthcare, 13(11), 1299. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111299