1. Introduction

Smoking during pregnancy poses substantial risks to maternal and neonatal health, contributing to adverse outcomes such as stillbirth, preterm birth, birth defects, and low birth weight [

1]. Despite efforts to address this issue, maternal mortality and morbidity rates in Alabama continue to exceed national benchmarks, driven in part by high smoking prevalence among reproductive-age women and barriers to accessing prenatal care [

2]. According to the Alabama Maternal Mortality Review Committee, pregnancy-related mortality and near-miss events remain alarmingly high despite declines at the national level, highlighting the need for a localized understanding of delayed or suboptimal care [

3]. More crucially, regional studies have documented significant barriers impeding timely prenatal care utilization, such as transportation deficits, appointment delays, and stigma-driven informational gaps [

2,

3,

4]. These barriers collectively exacerbate the challenges faced by pregnant women, particularly smokers, in accessing essential healthcare services.

Historically, U.S. policy has alternated between punitive measures, such as criminalizing prenatal substance use, and public health-focused interventions aimed at providing support [

5]. In states like Alabama, the chemical endangerment law categorizes prenatal substance use as child endangerment, deterring some women from seeking care due to fear of legal repercussions [

6,

7]. In addition, the burden of disease and disability associated with smoking during pregnancy is continually changing. Therefore, it is essential to prioritize and update our understanding of the structural and social factors that contribute to this public health challenge to improve outcomes for those affected by this issue. Furthermore, long-term maternal outcomes, such as postpartum morbidity and mental health challenges, remain insufficiently addressed, particularly in settings where substance use stigma is prevalent [

8,

9].

While significant efforts have been made over the past decades to lessen the risks associated with smoking during pregnancy among women of reproductive age, substantial gaps remain in contextualizing the psychosocial factors that contribute to this problem and how to galvanize community action to address this ongoing health issue [

10]. Interestingly, past research has shown that psychosocial and behavioral interventions, like contingency management, motivational support, and cognitive behavioral therapies, are crucial to addressing substance use during pregnancy [

11]. Notwithstanding, establishing and implementing innovative, sustained strategies that can help identify at-risk pregnant women early and connect them to treatment remains a significant challenge in resource-constrained settings, underscoring the critical importance of information-seeking during the prenatal period.

Moreover, geographic factors and cultural nuances play a critical role in shaping the burden and disability associated with smoking during pregnancy, varying significantly across diverse care settings. The prevailing perspective suggests that culture significantly shapes behavior and communication, with its intricate nuances influencing beliefs and perceptions regarding substance and alcohol use [

12]. This insight underscores the importance of uncovering the multifaceted dynamics and interconnected factors that drive pregnant women affected by substance use to seek, access, and successfully receive care.

Against this backdrop, the Three Delays Model provides a structured framework to categorize and address multifaceted barriers at critical points in the prenatal care continuum [

13]. This framework identifies delays in seeking care, reaching healthcare facilities, and receiving adequate care, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of the obstacles that impact maternal and infant health outcomes. Delays in seeking care are often related to various factors, including informational barriers, insufficient awareness about pregnancy signs, and hesitancy in recognizing the importance of prenatal care. Systemic factors, such as transportation difficulties or clinic access issues, contribute to delays in reaching care [

2,

9], and delays in receiving care reflect structural barriers, such as long wait times and unsupportive clinic environments.

In the context of Alabama, these barriers are amplified by stigma and systemic challenges, making it crucial to employ frameworks like the Three Delays Model to improve maternal health outcomes. This study applies the Three Delays Model to assess whether informational, structural, and system barriers confound and thereby attenuate the crude association between prenatal smoking and maternal health.

Accordingly, the study tests two hypotheses:

Higher levels of prenatal care barriers, especially informational and system domains, are associated with poorer self-reported maternal health;

Adjusting for these barrier domains will substantially weaken or eliminate the crude association between prenatal smoking and poor maternal health.

Conceptual Framework and Study Aims

The Three Delays Model lists or delineates three stages at which barriers can impede prenatal care [

13]:

- I.

Delay 1 (Decision to Seek Care): This domain or phase focuses on informational/sociocultural barriers. It touches on issues like a lack of pregnancy awareness, fear of legal repercussions, or stigma that discourages the initial decision to seek care;

- II.

Delay 2 (Reaching Care): This phase or domain focuses on structural barriers, including transportation problems, work/school conflicts, childcare responsibilities, or out-of-pocket costs that obstruct travel to a facility;

- III.

Delay 3 (Receiving Care): This phase or domain highlights system barriers, including appointment availability, insurance restrictions, or provider delays that hinder the timely receipt of services once a facility is reached.

In this study, prenatal smoking serves as the exposure, while self-reported maternal health is the outcome. The three delay-domain barriers are evaluated as potential confounders that may attenuate the crude smoking health association. Because some barriers, such as stigma-related informational deficits, can both influence smoking behavior and directly impact health, treating them as confounders aligns with current causal-inference guidance [

14,

15]. Accordingly, the study addresses two aims:

Estimate the independent associations between each delay-domain barrier and maternal health status;

Determine whether adjusting for informational, structural, and system barriers reduces or eliminates the crude association between prenatal smoking and poor maternal health, after controlling for age, race/ethnicity, income, and BMI.

2. Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study utilized secondary de-identified data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) Phase 8 survey (2016–2021; N = 533) provided by the Alabama Department of Public Health. PRAMS is administered to women who have recently delivered a live infant and captures maternal behaviors and attitudes during pregnancy and the early postpartum period, typically 2–4 months after birth. The population of interest comprised women who experienced live births in Alabama from 2016 to 2021. The initial PRAMS Phase 8 data set used for analysis comprised 596 observations, deliberately selected based on key variables essential to addressing the research question, study aims, and the relevance of the Three Delays Model or framework. A total of 63 records missing any key variables were excluded, with listwise deletion applied across all analyses.

2.1. Measures

The study variables were conceptualized using the Three Delays Model. The outcome, maternal health status, was derived from PRAMS Qn22 items and dichotomized as good vs. poor based on self-report. Although PRAMS captures multiple substances, cigarette items showed the highest response reliability; prenatal smoking was measured with Qn42_CigaretteCategory (“In the last 3 months of your pregnancy, how many cigarettes on an average day?”) and recoded 0 = non-smoker, 1 = any smoking.

Delay-domain confounders

Delay 1—Informational barriers: latent trait θ_info from IRT modelling of Qn21i (I didn’t know I was pregnant), Qn21j (I didn’t want anyone else to know), and Qn21k (I didn’t want prenatal care), capturing stigma-related knowledge deficits;

Delay 2—Structural barriers: sum of Qn21b (financial constraints) + Qn21f (work/school conflicts) + Qn21h (no childcare);

Delay 3—System barriers: sum of Qn21a (appointment availability) + Qn21d (insurance/plan delays).

The covariates were age group (15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, and ≥40 y), race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic), household income (Qn79 categories), and BMI category (underweight, healthy, and overweight, obese).

Table 1 provides operational definitions, coding schemes, and the Qn21 mapping to delay domains;

Appendix A (

Table A2) lists full PRAMS wording for each barrier item.

Factors that influence substance use and smoking during pregnancy among women of reproductive age are multifaceted [

16,

17,

18]. Addressing this intractable public health crisis requires the application of an appropriate theoretical framework coupled with a steadfast commitment to sustainable resource allocation. This study employs the Three Delays Framework to provide critical insights into the multifaceted challenges women experience when seeking prenatal care services during pregnancy [

13]. By capturing the interplay of individual, community, and health system factors, this framework offers a structured approach to identifying modifiable barriers and their linkages, offering opportunities for effective policy realignment and addressing implementation gaps.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated to summarize sample characteristics and variable distributions. Multidimensional scaling (MDS) and hierarchical clustering techniques were used to assess the grouping of prenatal care barrier items. Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha (α) and McDonald’s omega (ω). Despite the low reliability estimates (ω = 0.11, 0.07, 0.14), the composites were retained because the items represent theoretically coherent domains within the Three Delays framework, and the study is intentionally exploratory. Item response theory (IRT) modeling was then applied to derive the latent informational barrier trait (θ_info), accounting for item difficulty and discrimination.

Age categories were collapsed into three groups (15–24, 25–34, and ≥35 years), while household income was categorized as ≤USD 20k, USD 20–40k, and >USD 40k to ensure adequate cell sizes. Multivariable logistic regression was the sole inferential technique employed. The baseline model included smoking status and sociodemographic covariates (age band, race/ethnicity, income band, and BMI). A second model incorporated informational, structural, and system barriers as confounders. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported, and model fit was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test and variance-inflation diagnostics, with no multicollinearity detected.

The adjusted model was specified as follows:

All analyses were conducted in R 4.4.2 using the following packages: dplyr, tidyr, psych, and broom.

3. Results

The initial PRAMS Phase 8 data set comprised 596 observations. After excluding 63 records with missing key variables (listwise deletion), 533 remained for analysis.

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Table 2 displays frequencies and percentages for all key study variables (maternal health status, smoking status, income, BMI, age group, and race/ethnicity), except for the Qn21 barrier item frequencies, which are moved to

Table A1 for ease of reading. For example, 53.8% of respondents were classified as having good maternal health, while 46.2% had poor maternal health. In addition, 60.2% were categorized as non-smokers, and 39.8% were smokers.

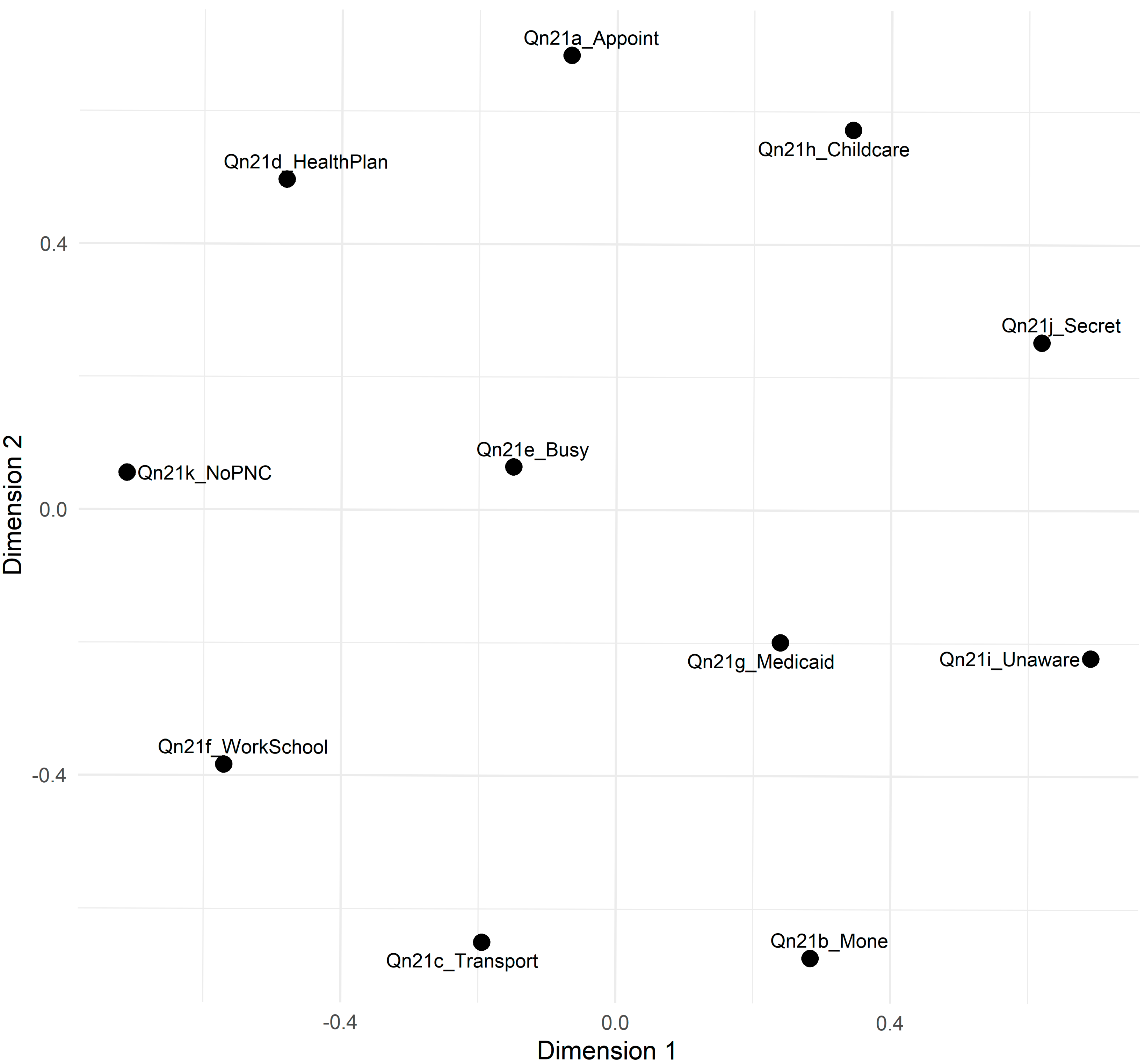

3.2. IRT-Derived Informational Barriers

Figure 1 shows the two-dimensional MDS plot, where items cluster in patterns suggestive of distinct barrier domains. Items associated with financial or scheduling constraints, like

I didn’t have enough money or insurance to pay for my visit (Qn21b) and

I couldn’t get an appointment (Qn21a), appeared in one region, and items reflecting knowledge or secrecy barriers, like

I didn’t know that I was pregnant (Qn21i), and

I didn’t want anyone else to know I was pregnant (Qn21j), appeared in another. These patterns provide initial evidence that these items may capture multiple underlying dimensions of prenatal care barriers, aligning partially with the Three Delays Model. For a full list of the Qn21 items and their corresponding barrier domains, please refer to

Table A2 (

Appendix A).

To assess the relationship between different types of delays (seeking, reaching, and receiving care) and maternal health status, bivariate analyses were conducted using chi-square tests. The results indicated that the Delay Seeking factor was significantly associated with maternal health status (χ2(3) = 23.11, p < 0.001). In contrast, the Delay Reaching (χ2(1) = 2.59, p = 0.462) and Delay Receiving (χ2(1) = 4.42, p = 0.229) factors showed no significant associations. These findings suggest that, at the bivariate level, variations in Delay Seeking are the only factor significantly linked to differences in maternal health outcomes.

Expanding on these bivariate findings, it is noteworthy that although the Delay in Seeking barrier showed a significant bivariate association with maternal outcomes (χ2(3) = 23.11, p < 0.001), this effect was not retained in the multivariable models, suggesting that its impact is confounded or mediated by other barriers.

3.3. Multivariable Logistic Regression

Baseline results, which included smoking status and sociodemographic covariates, showed no significant association between prenatal smoking and poor maternal health (OR = 0.83, 95% CI [0.58, 1.17]). After adjusting for informational, structural, and system barriers as confounders, the association further attenuated and remained non-significant (adjusted OR = 0.72, 95% CI [0.50, 1.03]). Informational barriers (OR = 2.42,

p < 0.001) and system-level barriers (OR = 1.77,

p = 0.047) were the only factors that significantly increased the odds of poor maternal health, whereas structural barriers were not statistically significant. Model calibration was adequate (Hosmer–Lemeshow

p = 0.61), and variance-inflation factors were ≤1.7, indicating no multicollinearity.

Table 3 provides the full model estimates, while the baseline versus adjusted smoking odds ratio is listed in

Appendix B,

Table A3.

As shown in

Table 3, after controlling for sociodemographic factors and the three delay domains, informational and system barriers, rather than smoking status, emerge as the strongest determinants of poor maternal health.

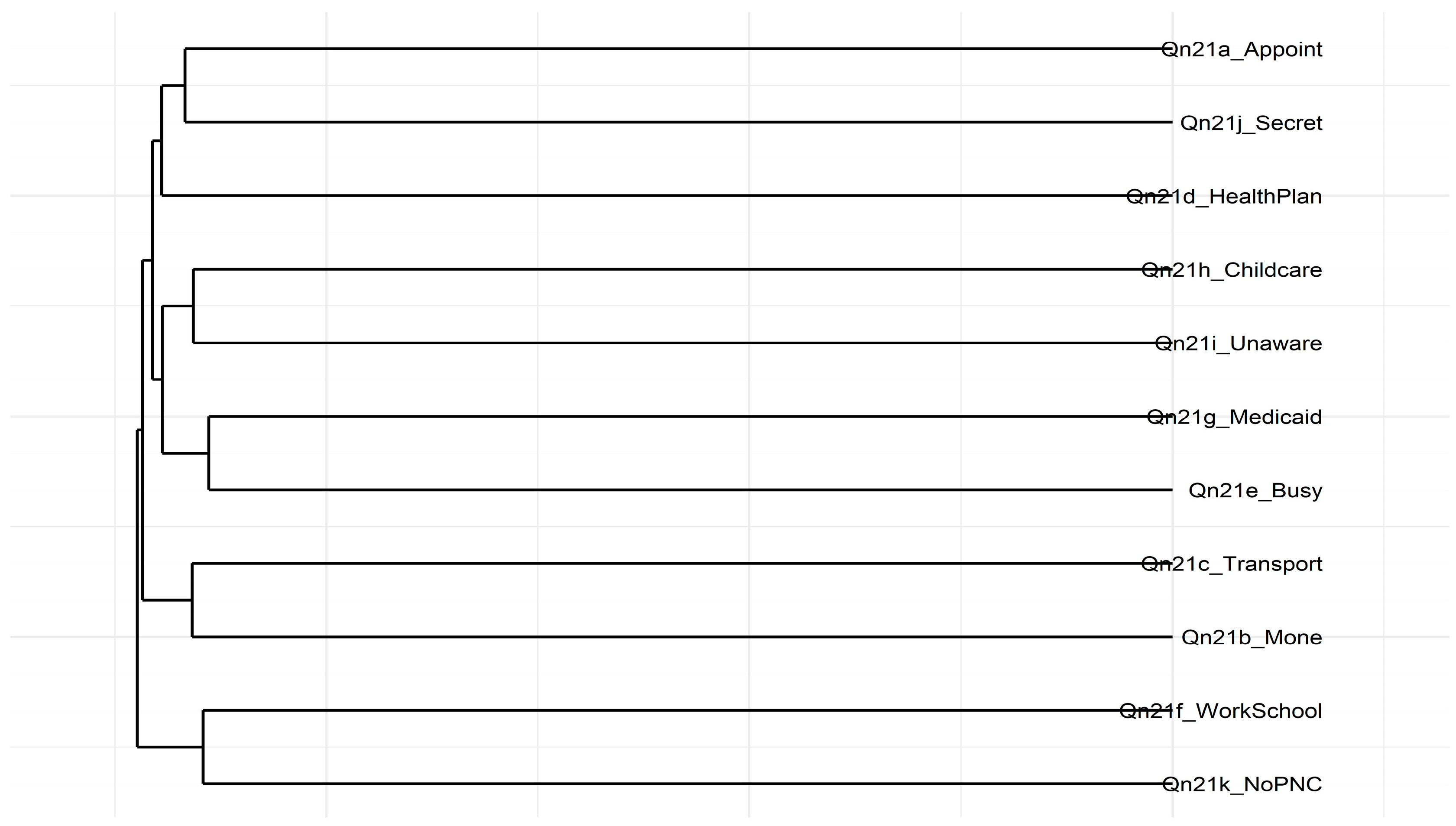

3.4. Hierarchical Clustering Analysis

A hierarchical clustering analysis was performed to identify distinct groups of prenatal care barriers. This method shows how specific barriers cluster together, offering insights into their relationships and guiding targeted perinatal interventions.

Figure 2 depicts the hierarchical clustering dendrogram for the Qn21 items, which were hypothesized as representing different domains of prenatal care barriers. Several notable clusters emerged.

For instance, I didn’t have enough money or insurance to pay for my visit (Qn21b), and I couldn’t take time off from work or school (Qn21f) are grouped, showing a potential overlap in financial and work-related constraints. Similarly, I didn’t have my Medicaid card (Qn21g), I had too many other things going on (Qn21e), and I didn’t know that I was pregnant (Qn21i) formed another cluster, revealing a set of logistical or knowledge-related barriers. Conversely, I didn’t want anyone else to know I was pregnant (Qn21j), and I didn’t want prenatal care (Qn21k) appeared as a distinct pair, potentially capturing personal or privacy concerns associated with pregnant women not seeking prenatal care.

These groupings largely align with the patterns observed in the Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) analysis shown in

Figure 1. However, the dendrogram does not wholly separate the items into three discrete clusters corresponding to the Three Delays Model. Instead, the results suggest that some barriers, like money and work constraints, may cut across multiple theoretical domains. Composite scores for each cluster were created to understand their relationship to maternal health outcomes. Further steps involve refining these item groupings and examining how they relate to maternal health outcomes.

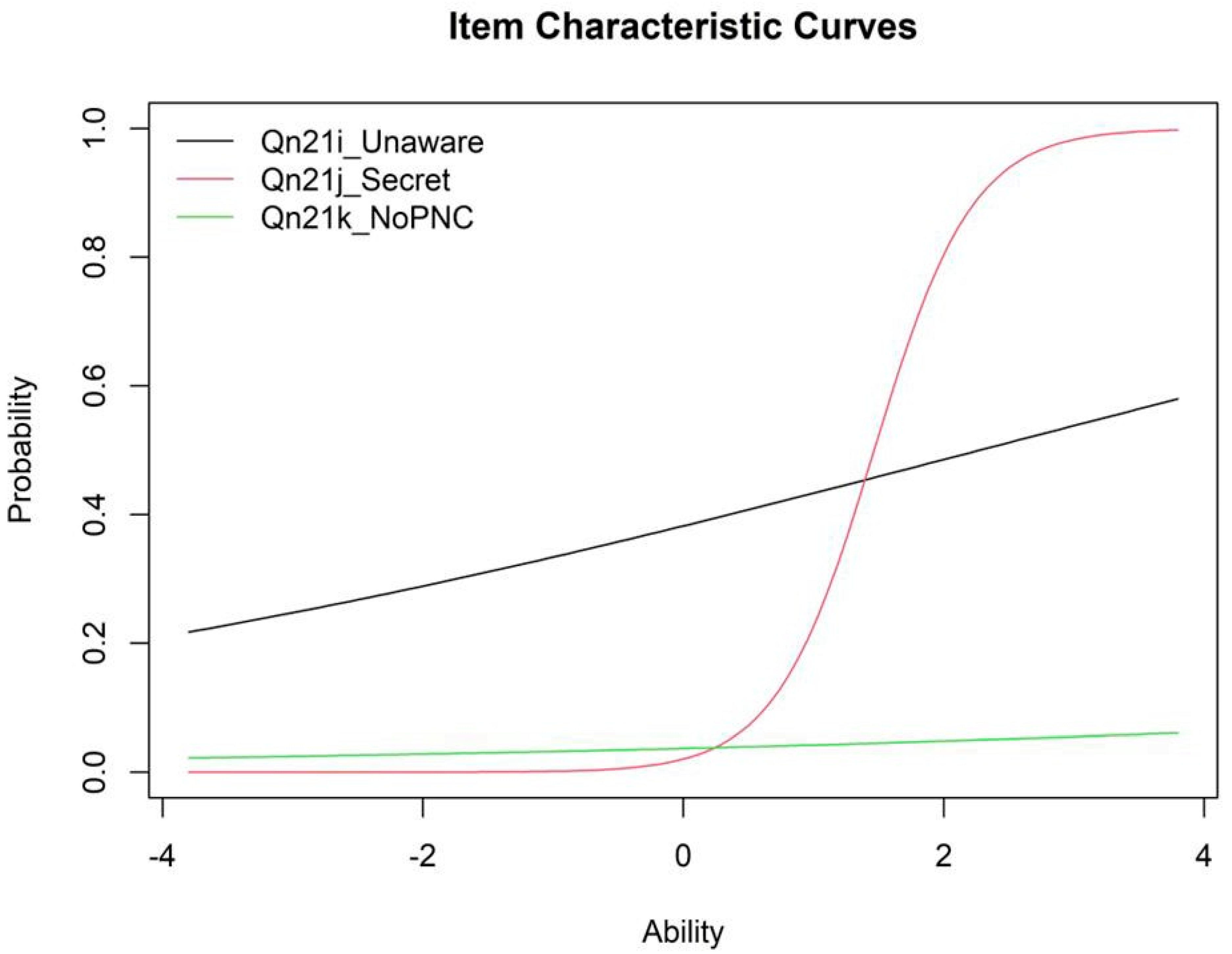

3.5. Item Characteristics Curves

Figure 3 illustrates the item characteristic curves (ICCs) for the informational barriers’ items, underscoring their discriminative properties under a two-parameter logistic (2PL) IRT model. For instance,

I didn’t know that I was pregnant (Qn21i) portrays a relatively flat slope, indicating low discrimination. In contrast,

I didn’t want anyone else to know I was pregnant (Qn21j) shows a sharply declining curve, consistent with its strong discrimination and high negative loading, and

I didn’t want prenatal care (Qn21k) demonstrates a steep slope, reflecting moderate-to-high discrimination.

These patterns show that I didn’t want anyone else to know I was pregnant (Qn21j) and I didn’t want prenatal care (Qn21k) are particularly effective in differentiating respondents along the latent trait of informational barriers, while I didn’t know that I was pregnant (Qn21i) contributes less to differentiation. Despite the limited discrimination of I didn’t know that I was pregnant (Qn21i), the items collectively capture a meaningful latent construct of informational barriers to prenatal care.

The ICCs visually highlight how each item differentiates across levels of the latent trait, further emphasizing the critical role of informational barriers in understanding maternal health outcomes. Although I didn’t know that I was pregnant (Qn21i) demonstrated low discrimination, it was retained to preserve theoretical completeness. Future studies may consider excluding this item.

4. Discussion

This cross-sectional study is the first to extend the Three Delays Model to prenatal smoking, identifying system and informational barriers, rather than structural constraints or smoking itself, as the primary factors associated with poor maternal health. Fear of mandatory reporting and its related stigma likely exacerbate Delay 1, discouraging pregnant smokers from seeking timely care [

6,

7,

19]. Although the Three Delays Model is widely applied in maternal health research [

13,

20,

21], its use in examining smoking during pregnancy remains limited. The study findings indicate that informational and system barriers independently predict adverse maternal outcomes and substantially attenuate the crude smoking health association, emphasizing the need for tailored educational campaigns that enhance awareness and navigation of prenatal services among high-risk populations.

To align with the Three Delays framework, prenatal care barriers were categorized into structural, informational, and system domains. Consistent with previous PRAMS analyses in Alabama [

2], Georgia [

3], and Mississippi [

4], as well as national maternal health reports [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28], informational and system barriers remained significant even after adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, income, and BMI. These barriers align with broader frameworks addressing substance use during pregnancy, such as contextual models of opioid crises [

22]. Additionally, polysubstance use, combining smoking with alcohol or opioids, worsens prenatal health disparities [

23], reinforcing the importance of maternal healthcare strategies designed to address worsening outcomes [

24,

25]. Global maternal health guidelines stress the need for equitable access to care, highlighting targeted prenatal outreach for high-risk populations [

26].

Since the barrier domains act as confounders rather than mediators in the adjusted multivariable logistic regression model, the exploratory mediation and SEM outputs remain available in

Appendix B (

Table A3 and

Table A4) for readers interested in alternative causal specifications. However, these supplementary analyses do not alter the primary conclusion that informational and system barriers are the predominant contributors to poor maternal health in this cohort. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to assess mediation pathways, following methodological best practices for response shift detection and item response theory applications [

27,

28]. Findings from Tennessee PRAMS further reinforce these patterns, highlighting persistent disparities in maternal health access [

29]. These results suggest that interventions addressing informational deficits, such as culturally tailored prenatal education modules, and system frictions, including appointment availability and insurance navigation, may yield greater improvements in maternal health than smoking-cessation messaging alone.

4.1. Implications for Theory and Practice

The study findings highlight the value of the Three Delays Model for analyzing barriers to prenatal care and their influence on maternal outcomes. System and informational barriers emerged as the most vital obstacles for pregnant smokers: inadequate appointment availability, insurance hurdles, and limited knowledge about prenatal services compound the challenges of navigating care.

Low maternal health literacy has long been linked to sub-optimal maternal and child health outcomes, including reduced access to essential services [

30]. Likewise, language barriers and health communication anxiety among linguistic minorities can exacerbate disparities [

31], while cultural norms and health-seeking behaviors shape service use in rural or diverse communities [

32].

Importantly, disparities in postpartum care reinforce the need for equitable approaches. Interrante et al. [

33] showed that race, geography, and insurance type affect receipt of recommended postpartum visits, underscoring the interconnected social and structural determinants of health. Shang et al. [

9] demonstrated that early, targeted postpartum interventions reduce depression and anxiety among women with pregnancy complications, and Pacho et al. [

34] found that substance use during pregnancy increases the risk of postpartum depression. Culturally tailored health education materials have been shown to improve patient engagement and health outcomes, especially among underserved populations [

35].

Practical recommendations include establishing integrated antenatal substance counselling clinics and adopting a “no wrong door” referral system so that patients receive needed services regardless of entry point. Routine postpartum follow-ups are also essential to maintain continuity of care. In Alabama, interventions should prioritize easy-to-understand, culturally tailored prenatal care information and community support referrals, complemented by case management services to sustain health gains. Addressing systemic issues, such as appointment scheduling, transportation, and insurance barriers, should be a policy priority. Investments in telehealth and mobile clinics could further reduce geographic inequities.

Because informational and system barriers confound the smoking health association, tackling these domains may yield substantial improvements in maternal health beyond smoking cessation messaging alone.

4.2. Study Limitations

This study has several limitations that merit consideration. First, it focuses exclusively on smoking as a substance use behavior. This tobacco-only focus may overlook broader substance use patterns, such as alcohol or opioid use, that also influence maternal health outcomes. Future PRAMS modules should expand their scope to capture the full spectrum of substance use during pregnancy.

Second, the study findings are specific to Alabama and may not generalize to other states or regions. PRAMS incorporates state-specific core questions and sampling methods, which may limit cross-state comparability. Notwithstanding, this geographic specificity is also a strength, as it provides actionable insights for policymakers and practitioners in Alabama’s unique demographic and healthcare context.

Third, several additional sociodemographic and reproductive variables like maternal education level, marital status, parity (number of children), and pregnancy intendedness, align with the Three Delays framework as potential influences on the decision to seek care (Delay 1) or the ability to reach care (Delay 2). For instance, maternal education shapes health literacy and recognition of prenatal needs, and marital status and household structure provide social support for transportation and childcare. Parity affects caregiving responsibilities, and pregnancy intendedness reflects motivation to engage in care.

However, a substantial portion of the complete-case sample had missing information on one or more of these variables, and including them in multivariable models would have markedly reduced the analytic sample and risked biased estimates. Although conceptually relevant, these factors were excluded to preserve analytic validity. Future research with more complete data should examine their specific roles within the prenatal care continuum.

Fourth, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences, and associations observed cannot establish temporal ordering or definitively confirm mediation versus confounding. Fifth, some composite measures exhibited low internal consistency, requiring advanced techniques such as item response theory (IRT) to derive latent traits. While IRT addresses reliability concerns, it may obscure item-level nuances. Qualitative studies or longitudinal designs could complement these findings by providing richer, context-specific insights into prenatal care barriers and their impact on maternal health.

5. Conclusions

In this cross-sectional analysis of PRAMS Phase 8 data from Alabama, the Three Delays Model was applied to examine how barriers to prenatal care influence maternal health among pregnant smokers. After adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, income, and BMI, smoking status was not significantly associated with poor maternal health (adjusted OR = 0.72, 95% CI [0.50, 1.03]). Instead, informational barriers (OR = 2.42, p < 0.001) and system-level barriers (OR = 1.77, p = 0.047) emerged as the strongest predictors.

These findings underscore that, although smoking remains a vital public health target, the most immediate opportunities for improving maternal health lie in addressing modifiable obstacles to care, such as increasing awareness of prenatal services and streamlining appointment and insurance processes. Mediation and SEM results have been moved to

Appendix B to ensure transparency while maintaining focus on the primary message that enhancing prenatal care utilization through targeted education campaigns and system-level reforms may yield greater improvements in maternal health than focusing exclusively on smoking cessation.

Future research should employ longitudinal designs, incorporate a broader set of sociodemographic and psychosocial covariates, and evaluate barrier-reduction strategies across diverse settings to confirm and extend these findings.