Trends of Korean Medicine Treatment for Parkinson’s Disease in South Korea: A Cross-Sectional Analysis Using the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service–National Patient Sample Database

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Source

2.2. Study Population

Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Calculation Methods

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethics Approval

3. Results

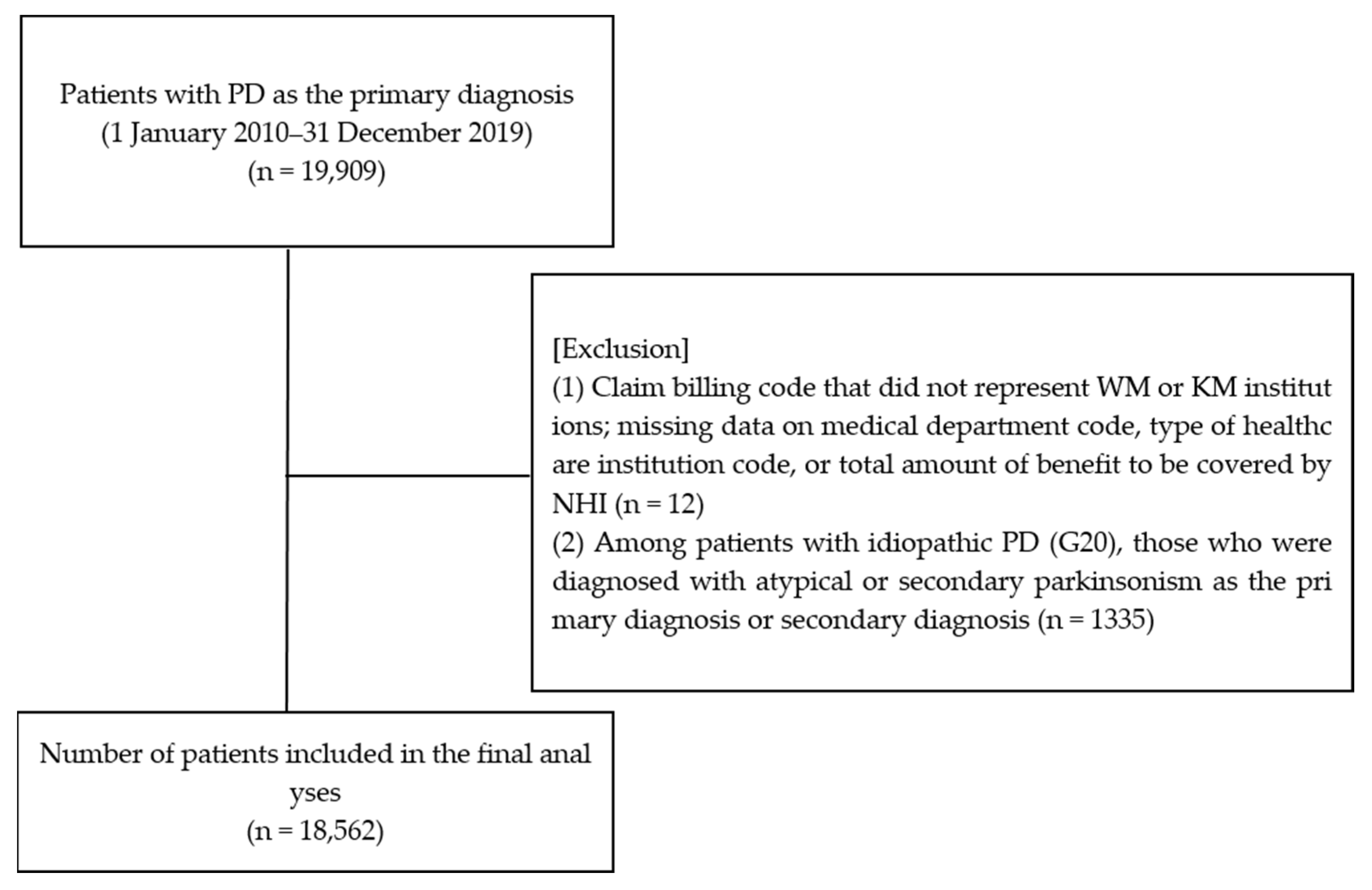

3.1. Patient Enrollment

3.2. Basic Patient Characteristics

3.3. Basic Medical Usage Characteristics

3.4. Annual Trends in the Total Number of Patients with PD Who Used Medical Services and the Ratio of KM Users

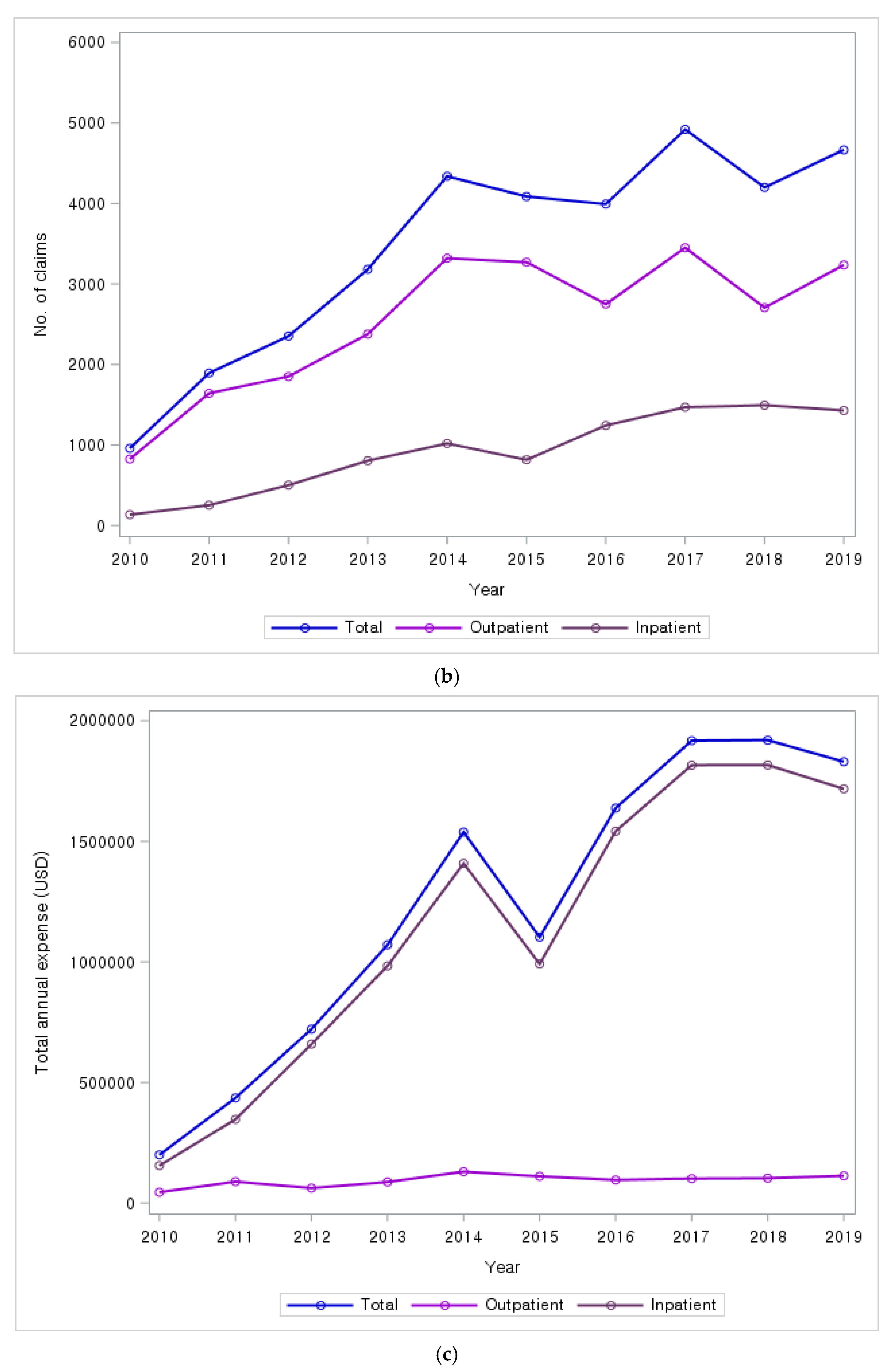

3.5. Annual Trends in the Number of Claims and Costs for Healthcare Utilization

3.6. Analysis of PD-Related KM Services Covered by NHI, Number of Claims, and Costs

3.7. Annual Trends in the Number of Claims and Costs for Major PD-Related KM Services Covered by NHI

3.8. Frequently Diagnosed Diseases in Claims for PD-Related KM Services

3.9. Analysis of WM Prescription Details for Patients with PD

3.10. Subgroup Analysis

3.10.1. Demographic Characteristics According to KM Utilization Frequency

3.10.2. Annual Trends and Patient Characteristics by KM Utilization and Anti-Dementia Drug Prescription

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAM | Complementary and alternative medicine |

| COMT | Catechol-o-methyl-transferase |

| HIRA | Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision |

| KM | Korean medicine |

| KPPS | King’s Parkinson’s disease Pain Scale |

| NHI | National Health Insurance |

| NPS | National Patient Sample |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| UPDRS | Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale |

| WM | Western medicine |

References

- Tansey, M.G.; Wallings, R.L.; Houser, M.C.; Herrick, M.K.; Keating, C.E.; Joers, V. Inflammation and immune dysfunction in Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 657–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, E.R. Principles of Nueral Science; Panmun Education Co., Ltd.: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2017; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, M.J.; Okun, M.S. Diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson disease: A review. JAMA 2020, 323, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Kim, S.; Suh, H.S. Current Status and Factors Affecting Prescription of Gastrointestinal Motility Drugs in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Yakhak Hoeji 2019, 63, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.h. Korean Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline for Parkinson’s Disease. In Representative Code: G20; National Institute for Korean Medicine Development; Koonja Publishing Inc.: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.E.; Choi, J.-k.; Lim, H.S.; Kim, J.H.; Cho, J.H.; Kim, G.S.; Lee, P.H.; Sohn, Y.H.; Lee, J.H. The prevalence and incidence of Parkinson’ s disease in South Korea: A 10-year nationwide population–based study. J. Korean Neurol. Assoc. 2017, 35, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2016 Statistics on Medical Expenses; Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service: Wonju-si, Republic of Korea, 2017.

- Kim, S.R.; Lee, T.Y.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, M.C.; Chung, S.J. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by Korean patients with Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2009, 111, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendran, P.R.; Thompson, R.E.; Reich, S.G. The use of alternative therapies by patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 2001, 57, 790–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, C.-L.; Wang, W.-W.; Lu, L.; Fu, D.-L.; Wang, X.-T.; Zheng, G.-Q. Epidemiology of complementary and alternative medicine use in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 20, 1062–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, H.S.; Yu, O.C.; Han, C.; Yang, K.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Moon, H.Y. A review on experimental studies of Parkinson’s disease in Korean medical journals. J. Orient. Neuropsychiatry 2017, 28, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.-B.; Kim, Y.-J.; Lee, H.-M.; Lee, H.-J.; Cho, S.-Y.; Park, J.-M.; Ko, C.-N.; Park, S.-U. Effects of Korean medicine on patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: A retrospective study. J. Intern. Korean Med. 2016, 37, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.-s.; Kim, H.-r.; Kim, S.-y.; Yim, T.-b.; Jin, C.; Kwon, S.; Cho, S.-y.; Jung, W.-s.; Moon, S.-k.; Park, J.-m. Effects of Korean Medicine on Pain in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Retrospective Study. J. Intern. Korean Med. 2020, 41, 947–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, M.; Kim, Y.; Choi, W.; Min, I.; Sun, J.; Hong, J.; Na, B.; Jung, W.; Moon, S.; et al. Case series of patients with parkinson syndrome visited in oriental medicine hospital. J. Soc. Stroke Korean Med. 2007, 8, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, L.; Kim, J.A.; Kim, S. A guide for the utilization of Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service National Patient Samples. Epidemiol. Health 2014, 36, e2014008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheon, C.; Jang, B.-H.; Ko, S.-G. A review of major secondary data resources used for research in traditional Korean medicine. Perspect Integr. Med. 2023, 2, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, J.L.; Valderrama-Chaparro, J.A.; Pinilla-Monsalve, G.D.; Molina-Echeverry, M.I.; Pérez Castaño, A.M.; Ariza-Araújo, Y.; Prada, S.I.; Takeuchi, Y. Parkinson’s disease prevalence, age distribution and staging in Colombia. Neurol. Int. 2020, 12, 8401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangpaisan, W.; Hori, H.; Brayne, C. Systematic review of the prevalence and incidence of Parkinson’s disease in Asia. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 19, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.W.; Kim, T.H.; Jin, C.; Jeon, J.H.; Choi, T.Y. Korean Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline for Parkinson’s Disease; National Institute for Korean Medicine Development: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.Y.; Jin, C.; Lee, J.; Lee, H.G.; Cho, S.Y.; Park, S.U.; Jung, W.S.; Moon, S.K.; Park, J.M.; Ko, C.N.; et al. Patients with Parkinson Disease in a Traditional Korean Medicine Hospital: A Five-Year Audit. Evid. Based Complement Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 6842863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.H.; Chiu, H.E.; Wu, S.Y.; Tseng, S.T.; Wu, T.C.; Hung, Y.C.; Hsu, C.Y.; Chen, H.J.; Hsu, S.F.; Kuo, C.E.; et al. Chinese Herbal Products for Non-Motor Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease in Taiwan: A Population-Based Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 615657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Z.; Geng, G.; Chen, W.; Dong, H.; Chen, L.; Zhan, S.; Li, T. Effectiveness and safety of acupuncture combined with madopar for parkinson—S disease: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Acupunct. Med. 2017, 35, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, H.; Kwon, S.; Cho, S.-Y.; Jung, W.-S.; Moon, S.-K.; Park, J.-M.; Ko, C.-N.; Park, S.-U. Effectiveness and safety of acupuncture in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Complement. Ther. Med. 2017, 34, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Lim, Y.W.; Kim, E.; Park, S.U. Review on the effect of acupuncture on Parkinson’s disease over the last 5 years. J. Korean Med. 2022, 43, 112–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.S.; Kim, H.R.; Kim, S.Y.; Yim, T.B.; Jin, C.; Kwon, S.W.; Cho, S.Y.; Jung, W.S.; Moon, S.K.; Park, J.M.; et al. Clinical characteristics of pain in patients with Parkinson’s disease who have visited a Korean medical hospital: A retrospective chart review. J. Korean Med. 2020, 41, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doo, K.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Cho, S.-Y.; Jung, W.-S.; Moon, S.-K.; Park, J.-M.; Ko, C.-N.; Kim, H.; Park, H.-J.; Park, S.-U. A prospective open-label study of combined treatment for idiopathic Parkinson’s disease using acupuncture and bee venom acupuncture as an adjunctive treatment. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2015, 21, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.R.; So, H.Y.; Choi, E.; Kang, J.H.; Kim, H.Y.; Chung, S.J. Influencing effect of non-motor symptom clusters on quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2014, 347, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, P.; Antonini, A.; Colosimo, C.; Marconi, R.; Morgante, L.; Avarello, T.P.; Bottacchi, E.; Cannas, A.; Ceravolo, G.; Ceravolo, R. The PRIAMO study: A multicenter assessment of nonmotor symptoms and their impact on quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2009, 24, 1641–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Hong, J.H.; Lee, P.H.; Son, Y.H.; Park, S.Y. The Incidence of Cognitive Decline (Mild Cognitive Impairment, Dementia) and Factors Affecting Cognitive Decline After the Onset of Parkinson’s Disease; Ilsan Hospital of the National Health Insurance Corporation: Goyang-si, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Jeon, B.S. Prevalence and Characteristics of Nonmotor Symptoms in Korean Parkinson’s Disease Patients and Its Relationship With Experience of Alternative Therapies. J. Korean Neurol. Assoc. 2013, 31, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.-Y.; Lee, J.-D.; Lee, S.-H.; Koh, H.-K. Anti-inflammatory Effect of Bee Venom Acupuncture at Sinsu (BL23) in a MPTP Mouse Model of Parkinson Disease. J. Acupunct. Res. 2009, 26, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Park, W.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, J.I.; Koh, H.K. Neuroprotective and Anti-inflammatory Effects of Bee Venom Acupuncture on MPTP-induced Mouse. J. Korean Acupunct. Moxibustion Soc. 2010, 27, 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Gazewood, J.D.; Richards, D.R.; Clebak, K. Parkinson disease: An update. Am. Fam. Physician 2013, 87, 267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.-H.; Lim, S. Clinical effectiveness of acupuncture on Parkinson disease: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2017, 96, e5836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Use of WM/KM Services | Total | Non-KM Users | KM Users | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | No. of Patients | Percentage (%) | No. of Patients | Percentage (%) | No. of Patients | Percentage (%) | |

| Total | 18,562 | 100.0 | 16,744 | 90.2 | 1797 | 9.6 | |

| Sex | Male | 7290 | 39.3 | 6653 | 39.7 | 630 | 35.1 |

| Female | 11,272 | 60.7 | 10,091 | 60.3 | 1167 | 64.9 | |

| Age (years) | <50 | 431 | 2.3 | 379 | 2.3 | 52 | 2.9 |

| 50–59 | 1447 | 7.8 | 1265 | 7.6 | 179 | 10.0 | |

| 60–69 | 3783 | 20.4 | 3393 | 20.3 | 388 | 21.6 | |

| ≥70 | 12,901 | 69.5 | 11,707 | 69.9 | 1178 | 65.6 | |

| Payer type | NHI | 16,456 | 88.7 | 14,823 | 88.5 | 1618 | 90.0 |

| Medicaid | 2026 | 10.9 | 1843 | 11.0 | 177 | 9.9 | |

| VHS | 80 | 0.4 | 78 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.1 | |

|

No. of Claims (Cases) |

Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 149,794 | 100.0 | |

| Type of visit | Outpatient | 119,414 | 79.7 |

| Inpatient | 30,380 | 20.3 | |

| Medical institutions | Hospitals (tertiary/general) | 83,710 | 55.9 |

| Convalescent hospitals | 31,971 | 21.3 | |

| Clinics | 17,984 | 12.0 | |

| KM hospitals | 2257 | 1.5 | |

| KM clinics | 13,380 | 8.9 | |

| Public health centers | 492 | 0.3 | |

| Rank | Diagnosis Code | Name of Diagnosis | No. of Claims (Cases) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (M00–M99) | 78,318 | 58.6 |

| 2 | U | Codes for special purposes (U00–U99) | 14,640 | 11.0 |

| 3 | S | Injury, poisoning, and certain other consequences of external causes (S00–T98) | 12,235 | 9.2 |

| 4 | R | Symptoms, signs, and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified (R00–R99) | 8776 | 6.6 |

| 5 | G | Diseases of the nervous system (G00–G99) | 7053 | 5.3 |

| 6 | K | Diseases of the digestive system (K00–K93) | 3243 | 2.4 |

| 7 | I | Diseases of the circulatory system (I00–I99) | 2874 | 2.2 |

| 8 | F | Mental and behavioral disorders (F00–F99) | 2142 | 1.6 |

| ATC Category | NHI Claims | Cost | Cost per Claim (USD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Claims (Cases) | Percentage (%) | Total Cost (USD) | Percentage (%) | ||

| Anti-Parkinson drugs | |||||

| Dopa and dopa derivatives | 5365 | 15.2 | 432,592 | 27.2 | USD 81 |

| Dopamine agonists | 3368 | 9.5 | 383,182 | 24.1 | USD 114 |

| Amantadine derivatives | 1359 | 3.8 | 19,529 | 1.2 | USD 14 |

| Monoamine oxidase B inhibitors | 911 | 2.6 | 127,181 | 8.2 | USD 140 |

| COMT inhibitor | 114 | 0.3 | 13,059 | 0.8 | USD 115 |

| Others | |||||

| Alimentary tract and metabolism | 4082 | 11.5 | 74,542 | 4.7 | USD 18 |

| Anti-dementia drugs | 4025 | 11.4 | 245,852 | 15.4 | USD 61 |

| Cardiovascular system | 3028 | 8.6 | 99,540 | 6.2 | USD 33 |

| Anxiolytics | 1739 | 4.9 | 11,374 | 0.7 | USD 7 |

| Pain medications | 1447 | 4.1 | 25,663 | 1.6 | USD 18 |

| Antidepressants | 1286 | 3.6 | 23,499 | 1.5 | USD 18 |

| Drugs for constipation | 1274 | 3.6 | 7784 | 0.5 | USD 6 |

| Blood and blood-forming organs | 1082 | 3.1 | 21,037 | 1.3 | USD 19 |

| Anticonvulsants | 976 | 2.8 | 4630 | 0.3 | USD 5 |

| Tertiary amines | 860 | 2.4 | 3556 | 0.2 | USD 4 |

| Other nervous system medications | 714 | 2.0 | 11,956 | 0.8 | USD 17 |

| Use of KM Services | Total | <20 | ≥20 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | No. of Patients | Percentage (%) | No. of Patients | Percentage (%) | No. of Patients | Percentage (%) | |

| Total | 1797 | 100.0 | 1559 | 86.8 | 238 | 13.2 | |

| Sex | Male | 630 | 35.1 | 521 | 33.4 | 109 | 45.8 |

| Female | 1167 | 64.9 | 1038 | 66.6 | 129 | 54.2 | |

| Age (years) | <50 | 52 | 2.9 | 45 | 2.9 | 7 | 2.9 |

| 50–59 | 179 | 10.0 | 143 | 9.2 | 36 | 15.1 | |

| 60–69 | 388 | 21.6 | 308 | 19.8 | 80 | 33.6 | |

| ≥70 | 1178 | 65.6 | 1063 | 68.2 | 115 | 48.3 | |

| KM ≥ 1 with Anti-Dementia Drug Prescription | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | Percentage (%) | No. of Claims | Percentage (%) | ||

| Total | 634 | 100.0 | 4025 | 100.0 | |

| Year | 2010 | 13 | 2.1 | 72 | 1.8 |

| 2011 | 26 | 4.1 | 156 | 3.9 | |

| 2012 | 32 | 5.1 | 187 | 4.7 | |

| 2013 | 52 | 8.2 | 345 | 8.6 | |

| 2014 | 76 | 12.0 | 480 | 11.9 | |

| 2015 | 73 | 11.5 | 415 | 10.3 | |

| 2016 | 90 | 14.2 | 622 | 15.5 | |

| 2017 | 84 | 13.3 | 590 | 14.7 | |

| 2018 | 92 | 14.5 | 621 | 15.4 | |

| 2019 | 96 | 15.1 | 537 | 13.3 | |

| KM ≥ 1 with Anti-Dementia Drug Prescription | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | Percentage (%) | ||

| Total | 634 | 100.0 | |

| Sex | Male | 201 | 31.7 |

| Female | 433 | 68.3 | |

| Age (years) | <50 | 1 | 0.2 |

| 50–59 | 25 | 3.9 | |

| 60–69 | 110 | 17.4 | |

| ≥70 | 498 | 78.6 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, B.; Kim, H.; Lee, Y.-S.; Lee, Y.J.; Jung, I.C.; Kim, J.Y.; Ha, I.-H. Trends of Korean Medicine Treatment for Parkinson’s Disease in South Korea: A Cross-Sectional Analysis Using the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service–National Patient Sample Database. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101207

Kim B, Kim H, Lee Y-S, Lee YJ, Jung IC, Kim JY, Ha I-H. Trends of Korean Medicine Treatment for Parkinson’s Disease in South Korea: A Cross-Sectional Analysis Using the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service–National Patient Sample Database. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101207

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, BackJun, Huijun Kim, Ye-Seul Lee, Yoon Jae Lee, In Chul Jung, Ju Yeon Kim, and In-Hyuk Ha. 2025. "Trends of Korean Medicine Treatment for Parkinson’s Disease in South Korea: A Cross-Sectional Analysis Using the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service–National Patient Sample Database" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101207

APA StyleKim, B., Kim, H., Lee, Y.-S., Lee, Y. J., Jung, I. C., Kim, J. Y., & Ha, I.-H. (2025). Trends of Korean Medicine Treatment for Parkinson’s Disease in South Korea: A Cross-Sectional Analysis Using the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service–National Patient Sample Database. Healthcare, 13(10), 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101207