Suicidal Ideation and Substance Use Among Middle and High School Students in Morocco

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection and Measures

2.4. Ethical Considerations and Procedure

2.5. Statistical Analyses

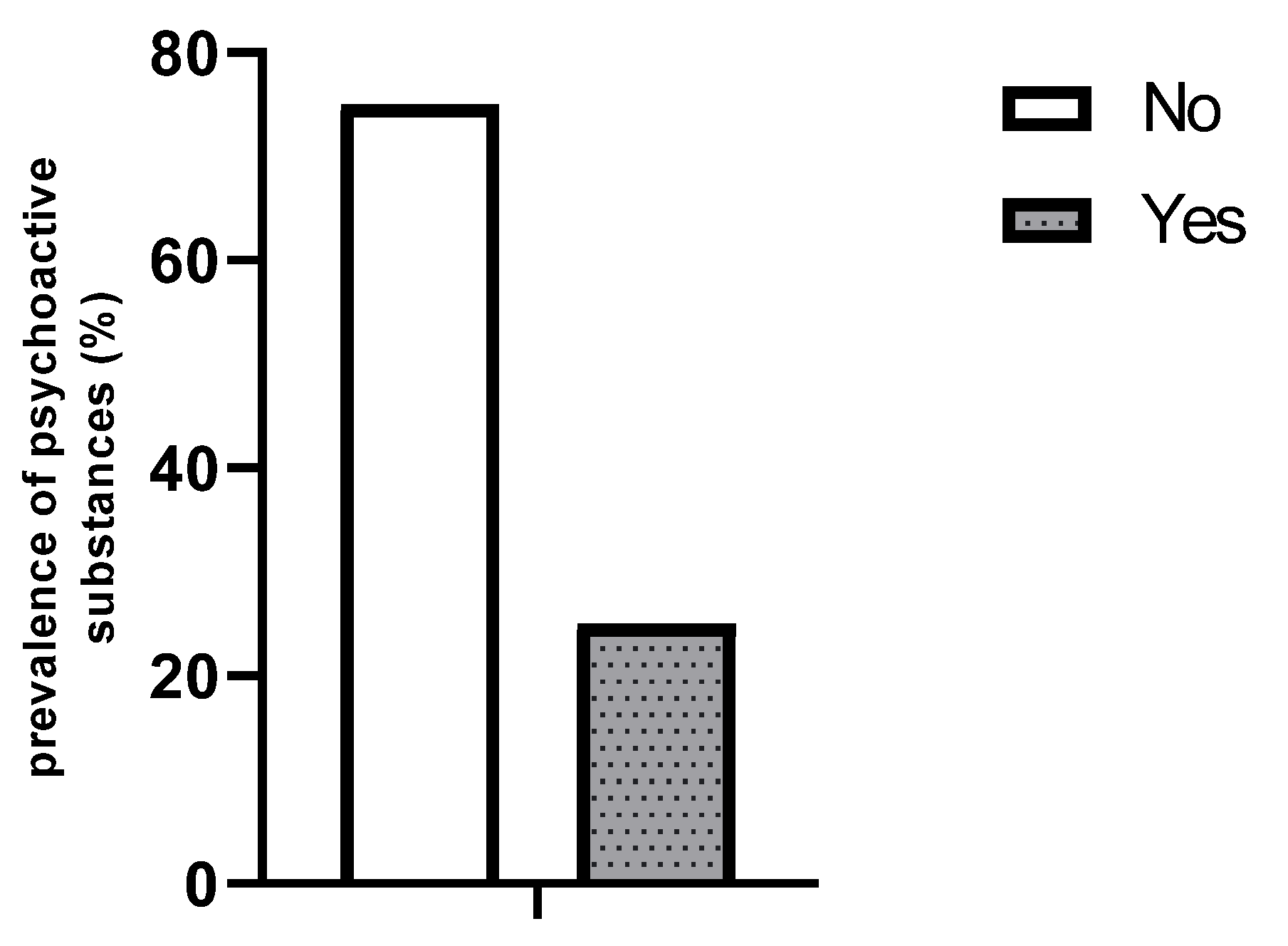

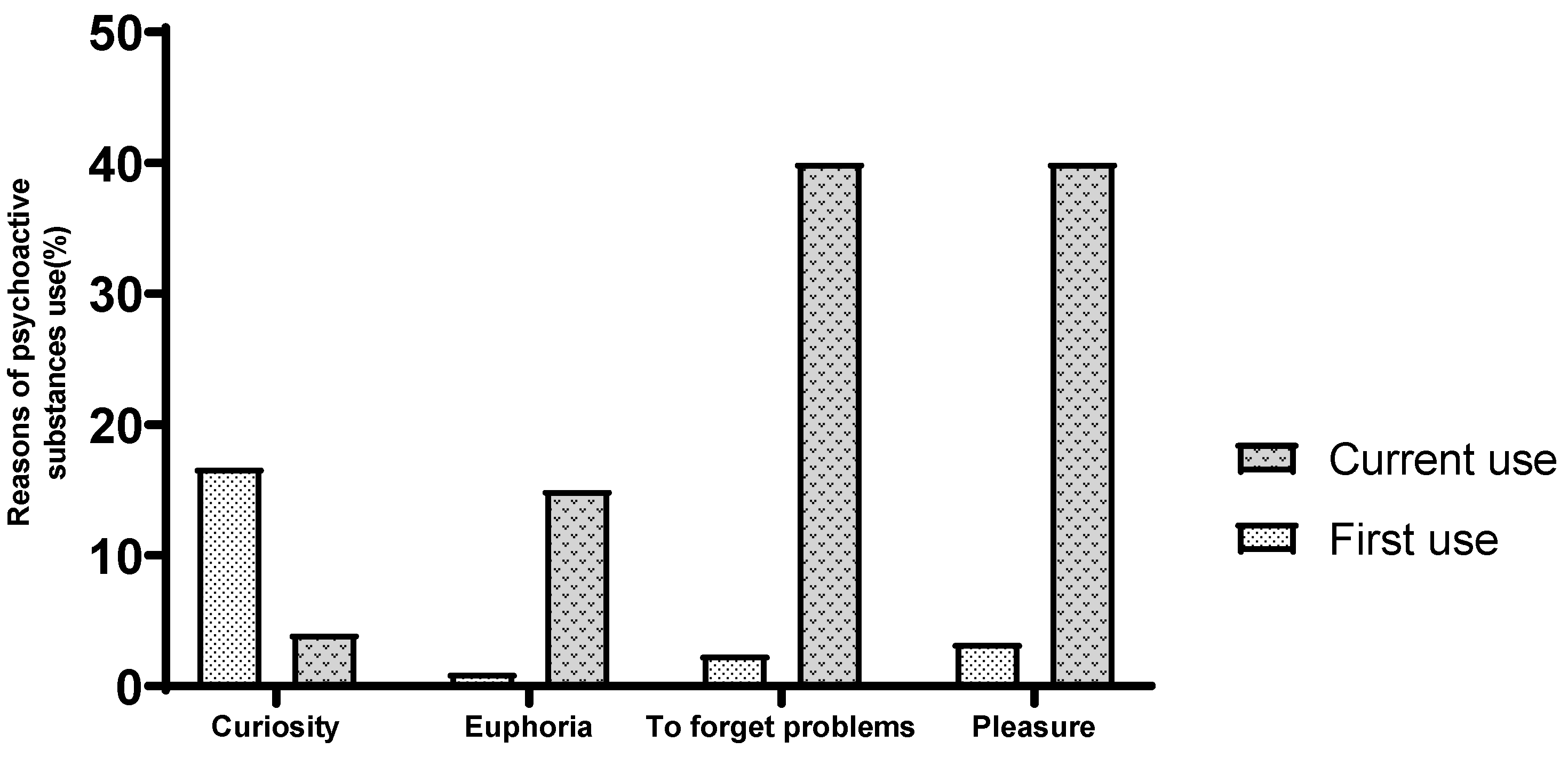

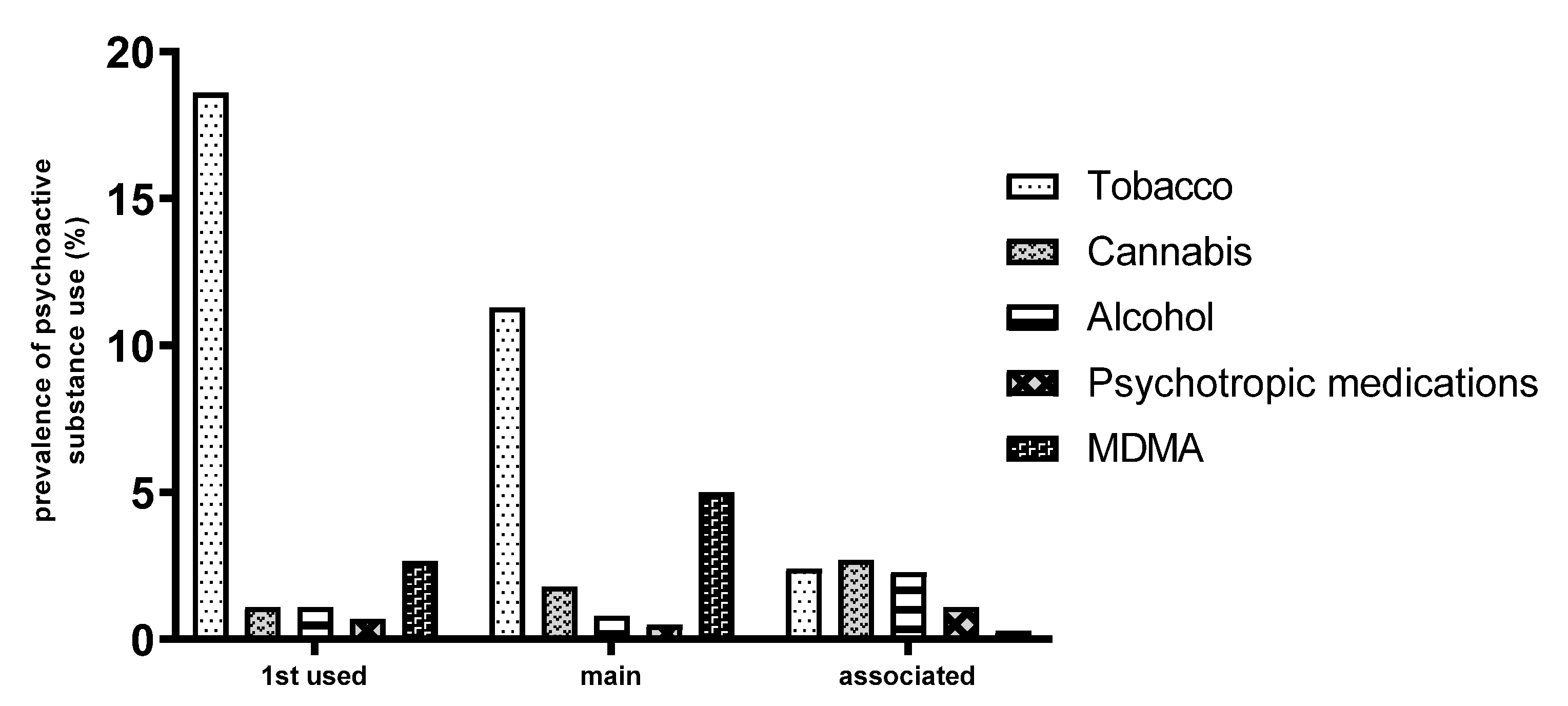

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE | Adverse Childhood Experiences |

| ASQ | Ask Suicide-Screening Questions |

| DSM | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |

| PAS | Psychoactive substance |

| SIDAS | Suicidal Ideation Attributes Scale |

| SUD | Substance use disorder |

References

- Poorolajal, J.; Haghtalab, T.; Farhadi, M.; Darvishi, N. Substance use disorder and risk of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt and suicide death: A meta-analysis. J. Public Health 2016, 38, e282–e291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suicidio. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Chang, B.; Gitlin, D.; Patel, R. The depressed patient and suicidal patient in the emergency department: Evidence-based management and treatment strategies. Emerg. Med. Pract. 2011, 13, 1–23; quiz 23–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aishvarya, S.; Maniam, T.; Sidi, H.; Oei, T.P.S. Suicide ideation and intent in Malaysia: A review of the literature. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, S95–S100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, W.M. SIQ, Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire: Professional Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, T.; Goodman, R.; Meltzer, H. The British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey 1999: The prevalence of DSM-IV disorders. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2003, 42, 1203–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arria, A.M.; O’Grady, K.E.; Caldeira, K.M.; Vincent, K.B.; Wilcox, H.C.; Wish, E.D. Suicide ideation among college students: A multivariate analysis. Arch. Suicide Res. 2009, 13, 230–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai Kwok, S.Y.; Shek, D.T. Hopelessness, parent-adolescent communication, and suicidal ideation among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2010, 40, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.-M.; Seo, D.-J.; Kim, K.-Y.; Park, R.-D.; Kim, D.-H.; Han, Y.-S.; Kim, T.-H.; Jung, W.-J. Nematicidal activity of 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid purified from Terminalia nigrovenulosa bark against Meloidogyne incognita. Microb. Pathog. 2013, 59–60, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breet, E.; Goldstone, D.; Bantjes, J. Substance use and suicidal ideation and behaviour in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, C.; Huet, A.-S.; Castellanos-Ryan, N.; Fortier, L.; Le Blanc, M.; Hamaoui, S.; Geoffroy, M.-C.; Renaud, J.; Séguin, J.R. Substance use disorders and suicidality in youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis with a focus on the direction of the association. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baslam, A.; Azraida, H.; Rachida, A.; Boussaa, S.; Chait, A. Epidemiological Association of Parental Substance Use History and Mental Health Disorders in Central Morocco. Psychiatr. Ann. 2024, 54, E56–E66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaif, E.R.; Sussman, S.; Newcomb, M.D.; Locke, T.F. Suicidality, depression, and alcohol use among adolescents: A review of empirical findings. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2007, 19, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, R.D.; Margulies, T.; Davis, R.; Karam, E. Hopelessness, depression, and suicide intent. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1980, 41, 159–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, N.; Amit, N.; Suen, M.W. Psychological factors as predictors of suicidal ideation among adolescents in Malaysia. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Joshi, H.L. Suicidal ideation in relation to depression, life stress and personality among college students. J. Indian Acad. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 34, 259–265. [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi, T.; Nakao, M. The relationship between suicidal ideation and symptoms of depression in Japanese workers: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e003643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaei, R.; Viitasara, E.; Soares, J.; Sadeghi-Bazarghani, H.; Dastgiri, S.; Zeinalzadeh, A.H.; Bahadori, F.; Mohammadi, R. Suicidal ideation and its correlates among high school students in Iran: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tom, A.; Mahfoud, Z.R. Factors associated with suicidality among school attending adolescents in morocco. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 885258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241564779 (accessed on 14 August 2023).

- Mulenga, D.; Kwangu, M.; Njunju, E.M.; Siziya, S.; Mazaba, M.L. Suicidal ideation prevalence and its associated factors among in-school adolescents in Morocco. Int. Public Health J. 2017, 9, 465. [Google Scholar]

- Baslam, A.; Boussaa, S.; Raoui, K.; Kabdy, H.; Aitbaba, A.; El Yazouli, L.; Aboufatima, R.; Chait, A. Prevalence of Substance Use and Associated Factors Among Secondary School Students in Marrakech Region, Morocco. Psychoactives 2025, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baslam, A.; Kabdy, H.; Aitbaba, A.; Aboufatima, R.; Boussaa, S.; Chait, A. Substance use among university students and affecting factors in Central Morocco: A cross-sectional Study. Acad. J. Health Sci. Med. Balear. 2023, 38, 146–153. [Google Scholar]

- Arterberry, B.; Boyd, C.; West, B.; Schepis, T.; McCabe, S. DSM-5 Substance Use Disorders Among College-Age Young Adults in the United States: Prevalence, Remission and Treatment. J. Am. Coll. Health 2020, 68, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inman, D.D.; Matthews, J.; Butcher, L.; Swartz, C.; Meadows, A.L. Identifying the risk of suicide among adolescents admitted to a children’s hospital using the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2019, 32, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Spijker, B.A.J.; Batterham, P.J.; Calear, A.L.; Farrer, L.; Christensen, H.; Reynolds, J.; Kerkhof, A.J. The Suicidal Ideation Attributes Scale (SIDAS): Community-Based Validation Study of a New Scale for the Measurement of Suicidal Ideation. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2014, 44, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, H.; Bate, J.; Steele, M.; Dube, S.R.; Danskin, K.; Knafo, H.; Nikitiades, A.; Bonuck, K.; Meissner, P.; Murphy, A. Adverse childhood experiences, poverty, and parenting stress. Can. J. Behav. Sci./Rev. Can. Des Sci. Comport. 2016, 48, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.W.; McGrath, P.J.; Quitkin, F.M.; Klein, D.F. DSM-IV Depression with Atypical Features: Is It Valid? Neuropsychopharmacology 2009, 34, 2625–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beardslee, W.R.; Jacobson, A.M.; Hauser, S.T.; Noam, G.V.; Powers, S. An Approach to Evaluating Adolescent Adaptive Processes: Scale Development and Reliability. J. Am. Acad. Child Psychiatry 1985, 24, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.A.; Fulkerson, J.A.; Beebe, T.J. DSM-IV Substance Use Disorder Criteria for Adolescents: A Critical Examination Based on a Statewide School Survey. Am. J. Psychiatry 1998, 155, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.G.; Harris, E.S.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The patient health questionnaire for adolescents: Validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. J. Adolesc. Health 2002, 30, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagwa. Fiche Explicative de la Leçon: Coefficient de Corrélation de Pearson|Nagwa. Available online: https://www.nagwa.com/fr/explainers/143190760373/ (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Zarrouq, B.; Bendaou, B.; Elkinany, S.; Rammouz, I.; Aalouane, R.; Lyoussi, B.; Khelafa, S.; Bout, A.; Berhili, N.; Hlal, H.; et al. Suicidal behaviors among Moroccan school students: Prevalence and association with socio-demographic characteristics and psychoactive substances use: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinsohn, P.M.; Rohde, P.; Seeley, J.R.; Baldwin, C.L. Gender differences in suicide attempts from adolescence to young adulthood. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2001, 40, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, L.T. Suicidal ideation and substance use among adolescents and young adults: A bidirectional relation? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 142, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breslau, N.; Schultz, L.R.; Johnson, E.O.; Peterson, E.L.; Davis, G.C. Smoking and the Risk of Suicidal Behavior: A Prospective Study of a Community Sample. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echeverria, I.; Cotaina, M.; Jovani, A.; Mora, R.; Haro, G.; Benito, A. Proposal for the Inclusion of Tobacco Use in Suicide Risk Scales: Results of a Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, F.L.; Peterson, E.L.; Lu, C.Y.; Hu, Y.; Rossom, R.C.; Waitzfelder, B.E.; Owen-Smith, A.A.; Hubley, S.; Prabhakar, D.; Williams, L.K.; et al. Substance use disorders and risk of suicide in a general US population: A case control study. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2020, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalla, R.R.; Miguel, A.C.; Brietzke, E.; Caetano, R.; Laranjeira, R.; Madruga, C.S. Suicidal behavior among substance users: Data from the Second Brazilian National Alcohol and Drug Survey (II BNADS). Braz. J. Psychiatry 2019, 41, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, E.; Spilka, S.; Beck, F. Suicide, santé mentale et usages de substances psychoactives chez les adolescents français en 2014. Rev. D’épidémiologie Santé Publique 2017, 65, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrouq, B.; Bendaou, B.; El Asri, A.; Achour, S.; Rammouz, I.; Aalouane, R.; Lyoussi, B.; Khelafa, S.; Bout, A.; Berhili, N.; et al. Psychoactive substances use and associated factors among middle and high school students in the North Center of Morocco: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.T.; Dedding, C.; Pham, T.T.; Wright, P.; Bunders, J. Depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation among Vietnamese secondary school students and proposed solutions: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, M.S.; King, R.; Greenwald, S.; Fisher, P.; Schwab-Stone, M.; Kramer, R.; Flisher, A.J.; Goodman, S.; Canino, G.; Shaffer, D. Psychopathology associated with suicidal ideation and attempts among children and adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1998, 37, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herba, C.M.; Ferdinand, R.F.; van der Ende, J.; Verhulst, F.C. Long-term associations of childhood suicide ideation. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2007, 46, 1473–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, D.C.R.; Owen, L.D.; Pears, K.C.; Capaldi, D.M. Prevalence of Suicidal Ideation Among Boys and Men Assessed Annually from Ages 9 to 29 Years. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2008, 38, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamis, D.A.; Lester, D. Gender differences in risk and protective factors for suicidal ideation among college students. J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 2013, 27, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.; Whisman, M.A. Negative affect and cognitive biases in suicidal and nonsuicidal hospitalized adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1996, 35, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Júnior, E.B.; Fernandes, M.N.; Gherardi-Donato, E.C. Echoes of Early-Life Stress on Suicidal Behavior in Individuals with Substance Use Disorder. Enfermería Actual de Costa Rica 2023. Available online: http://www.scielo.sa.cr/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1409-45682023000100008&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Liu, J.; Fang, Y.; Gong, J.; Cui, X.; Meng, T.; Xiao, B.; He, Y.; Shen, Y.; Luo, X. Associations between suicidal behavior and childhood abuse and neglect: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 220, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, C.; Shugart, M.; Craighead, W.E.; Nemeroff, C.B. Neurobiological and psychiatric consequences of child abuse and neglect. Dev. Psychobiol. 2010, 52, 671–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boeninger, D.K.; Masyn, K.E.; Feldman, B.J.; Conger, R.D. Sex differences in developmental trends of suicide ideation, plans, and attempts among European American adolescents. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2010, 40, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, L.E. Development Through the Lifespan, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Matud, M.P. Gender differences in stress and coping styles. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 37, 1401–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Suicidal Ideation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Modality | No (n = 657) | Yes (n = 134) | χ2 | p | Odds Ratio (OR) (IC 95%) | p |

| Age | Mean (±ET) | 15.98 (2.17) | 15.98 (2.07) | - | - | - | - |

| Gender | Female | 300 (45.7) | 77 (57.5%) | 6.2 | 0.01 | 1.16 (1.1–2.34) | 0.01 |

| Male | 357 (54.3) | 57 (42.5%) | 1 | ||||

| Parents | Biological | 648 (98.6%) | 127 (94.8%) | 10.74 | 0.005 | 0.29 (0.1–0.8) | 0.02 |

| Adoptive | 9 (1.4%) | 6 (4.5%) | 1 | ||||

| Educational Level | 1st M. School | 74 (11.3%) | 18 (13.4%) | Ns | Ns | Ns | Ns |

| 2nd M. School | 92 (14.0%) | 18 (13.4%) | |||||

| 3rd M. School | 109 (16.6%) | 19 (14.2%) | |||||

| 1st H. School | 105 (16.0%) | 24 (17.9%) | |||||

| 2nd H. School | 102 (15.5%) | 18 (13.4%) | |||||

| 3rd H. School | 175 (26.6%) | 37 (27.6%) | |||||

| Place of Residence | Rural | 154 (23.4%) | 14 (10.4%) | 12.4 | 0.006 | Ns | |

| Urban | 503 (76.6%) | 120 (89.6%) | |||||

| Father’s Working Status | No | 55 (8.4%) | 11 (8.2%) | Ns | Ns | Ns | ns |

| Yes | 602 (91.6%) | 123 (91.8%) | |||||

| Mother’s Working Status | No | 562 (85.5%) | 113 (84.3%) | Ns | Ns | Ns | ns |

| Yes | 95 (14.5%) | 95 (14.5%) | |||||

| Mother’s Medical History | No | 501 (76.3%) | 88 (65.7%) | 6.55 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Yes | 156 (23.7%) | 46 (34.3%) | 1.67 (1.12–2.5) | ||||

| Father’s Medical History | No | 536 (81.6%) | 101 (75.4%) | Ns | Ns | Ns | ns |

| Yes | 121 (18.4%) | 33 (24.6%) | |||||

| Mother’s Psychiatric History | No | 620 (94.4%) | 120 (89.6%) | 4.28 | 0.003 | 1 | 0.04 |

| Yes | 37 (5.6%) | 14 (10.4%) | 1.95 (1.02–3.72) | ||||

| Father’s Psychiatric History | No | 643 (97.9%) | 126 (94.0%) | 6.01 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Yes | 14 (2.1%) | 8 (6.0%) | 2.91 (1.19–7.09) | ||||

| Father’s Legal History | No | 641 (97.6%) | 122 (91.0%) | 13.85 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 16 (2.4%) | 12 (9.0%) | 3.94 (1.81–8.53) | ||||

| Mother’s Substance Use | No | 654 (99.5%) | 130 (97.0%) | 8.12 | 0.004 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Yes | 3 (0.5%) | 4 (3.0%) | 6.7 (1.48–30.32) | ||||

| Father’s Substance Use | No | 515 (78.4%) | 76 (56.7%) | 27.66 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 142 (21.6%) | 58 (43.3%) | 2.76 (1.87–4.08) | ||||

| Suicidal Ideation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Modality | No (n = 657) | Yes (n = 134) | χ2 | p | OR (IC 95%) | p |

| Parental Relationships | Very Good | 224 (34.1%) | 33 (24.6%) | 28.68 | <0.001 | 1 | |

| Good | 227 (34.6%) | 30 (22.4%) | ns | ||||

| Average | 193 (29.4%) | 61 (45.5%) | 2.14 (1.34–3.41) | 0.001 | |||

| Poor | 13 (2.0%) | 10 (7.5%) | 5.22 (2.11–12.86 | <0.001 | |||

| Sibling Relationships | Very Good | 204 (31.4%) | 28 (20.9%) | 33.82 | <0.001 | 0.37 (0.16–0.84) | 0.01 |

| Good | 316 (48.1%) | 47 (35.1%) | 0.4 (0.18–0.88) | 0.02 | |||

| Average | 108 (16.4%) | 49 (36.6%) | ns | ||||

| Poor | 27 (4.1%) | 10 (7.5%) | 1 | ||||

| Friend Relationships | Very Good | 183 (27.9%) | 31 (23.1%) | 13.36 | 0.004 | 1 | |

| Good | 309 (47.0%) | 49 (36.6%) | ns | ||||

| Average | 143 (21.8%) | 45 (33.6%) | 1.85 (1.11–3.08) | 0.01 | |||

| Poor | 22 (3.3%) | 9 (6.7%) | 2.41 (1.01–5.72) | 0.04 | |||

| Teacher Relationships | Very Good | 138 (21.0%) | 20 (14.9%) | 15.25 | 0.002 | 1 | |

| Good | 316 (48.1%) | 60 (44.8%) | ns | ||||

| Average | 171 (26.0%) | 36 (26.9%) | ns | ||||

| Poor | 32 (4.9%) | 18 (13.4%) | 3.88 (1.84–8.16) | <0.001 | |||

| Suicidal Ideation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Modality | No | Yes | χ2 | p | OR (IC 95%) | p |

| Sleep duration | >10 h | 71 (10.8%) | 30 (22.4%) | 64.39 | <0.001 | ns | |

| between 8 h and 10 h | 171 (26.0%) | 29 (21.6%) | |||||

| between 6 h and 8 h | 375 (57.1%) | 43 (32.1%) | |||||

| <4 h | 40 (6.1%) | 32 (23.9%) | |||||

| Medical history | No | 561 (85.4%) | 94 (70.1%) | 18.15 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 96 (14.6%) | 40 (29.9%) | 2.48 (1.62–3.81) | ||||

| Surgical history | No | 588 (89.5%) | 110 (82.1%) | 5.88 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 69 (10.5%) | 24 (17.9%) | 1.85 (1.12–3.08) | ||||

| Legal history | No | 637 (97.0%) | 123 (91.8%) | 7.88 | 0.005 | 1 | 0.007 |

| Yes | 20 (3.0%) | 11 (8.2%) | 2.84 (1.33–6.09) | ||||

| Suicidal Ideation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Modality | No | Yes | χ2 | p | OR (IC 95%) | p |

| Early trauma | No | 195 (29.7%) | 11 (8.2%) | 26.46 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 462 (70.3%) | 123 (91.8%) | 4.72 (2.49–8.94) | ||||

| DSM depression | No | 439 (66.8%) | 20 (14.9%) | 123 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 218 (33.2%) | 114 (85.1%) | 11.47 (6.94–18.96) | ||||

| DSM addiction | No | 588 (89.5%) | 102 (76.1%) | 22.00 | <0.001 | 1 | |

| Mild | 4 (0.6%) | 3 (2.2%) | Ns | ||||

| Moderate | 13 (2%) | 10 (7.5%) | 4.43 (1.89–10.38) | <0.001 | |||

| Severe | 52 (7.9%) | 19 (14.2%) | 2.10 (1.19–3.7) | <0.001 | |||

| Age at Onset | PAS Consumption Expenses (MAD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum | 7 | 20 |

| Maximum | 19 | 2500 |

| Mean | 14.28 | 454.83 |

| Standard Deviation (n) | 1.70 | 480 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (1) | r | 1 | 0.195 ** | 0.052 | 0.152 ** | 0.119 ** | −0.054 | 0.025 | 0.003 | 0.172 ** |

| p | 0.000 | 0.170 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.158 | 0.509 | 0.942 | 0.000 | ||

| Expenses (2) | r | 0.109 ** | 1 | 0.068 | 0.119 ** | 0.145 ** | 0.029 | 0.121 ** | 0.132 ** | 0.651 ** |

| p | 0.002 | 0.104 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.493 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.000 | ||

| ACE score (3) | r | 0.043 | 0.068 | 1 | 0.441 ** | 0.477 ** | 0.126 ** | 0.161 ** | 0.215 ** | 0.045 |

| p | 0.225 | 0.104 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.237 | ||

| DSM depression (4) | r | 0.182 ** | 0.119 ** | 0.441 ** | 1 | 0.503 ** | 0.193 ** | 0.552 ** | 0.523 ** | 0.077 * |

| p | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.043 | ||

| Suicidal risks (5) | r | 0.109 ** | 0.145 ** | 0.477 ** | 0.503 ** | 1 | 0.217 ** | 0.313 ** | 0.372 ** | 0.090 * |

| p | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.018 | ||

| Suicidal ideation at birth (6) | r | 0.011 | 0.029 | 0.126 ** | 0.193 ** | 0.217 ** | 1 | 0.236 ** | 0.300 ** | 0.044 |

| p | 0.754 | 0.493 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.252 | ||

| Suicidal ideation last month (7) | r | 0.048 | 0.121 ** | 0.161 ** | 0.552 ** | 0.313 ** | 0.236 ** | 1 | 0.732 ** | 0.127 ** |

| p | 0.176 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | ||

| SIADS (8) | r | 0.016 | 0.132 ** | 0.215 ** | 0.523 ** | 0.372 ** | 0.300 ** | 0.732 ** | 1 | 0.126 ** |

| p | 0.643 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | ||

| DSM substance abuse (9) | 0.173 ** | 0.651 ** | 0.045 | 0.077 * | 0.090 * | 0.044 | 0.127 ** | 0.126 ** | 1 | |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.237 | 0.043 | 0.018 | 0.252 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baslam, A.; Azraida, H.; Boussaa, S.; Chait, A. Suicidal Ideation and Substance Use Among Middle and High School Students in Morocco. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101178

Baslam A, Azraida H, Boussaa S, Chait A. Suicidal Ideation and Substance Use Among Middle and High School Students in Morocco. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101178

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaslam, Abdelmounaim, Hajar Azraida, Samia Boussaa, and Abderrahman Chait. 2025. "Suicidal Ideation and Substance Use Among Middle and High School Students in Morocco" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101178

APA StyleBaslam, A., Azraida, H., Boussaa, S., & Chait, A. (2025). Suicidal Ideation and Substance Use Among Middle and High School Students in Morocco. Healthcare, 13(10), 1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101178