Perceptions and Practices of Interdisciplinary Action in an Intra-Hospital Support Team for Palliative Care: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting, Participants, and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Ethical Procedures

2.5. Data Analysis and Trustworthiness

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

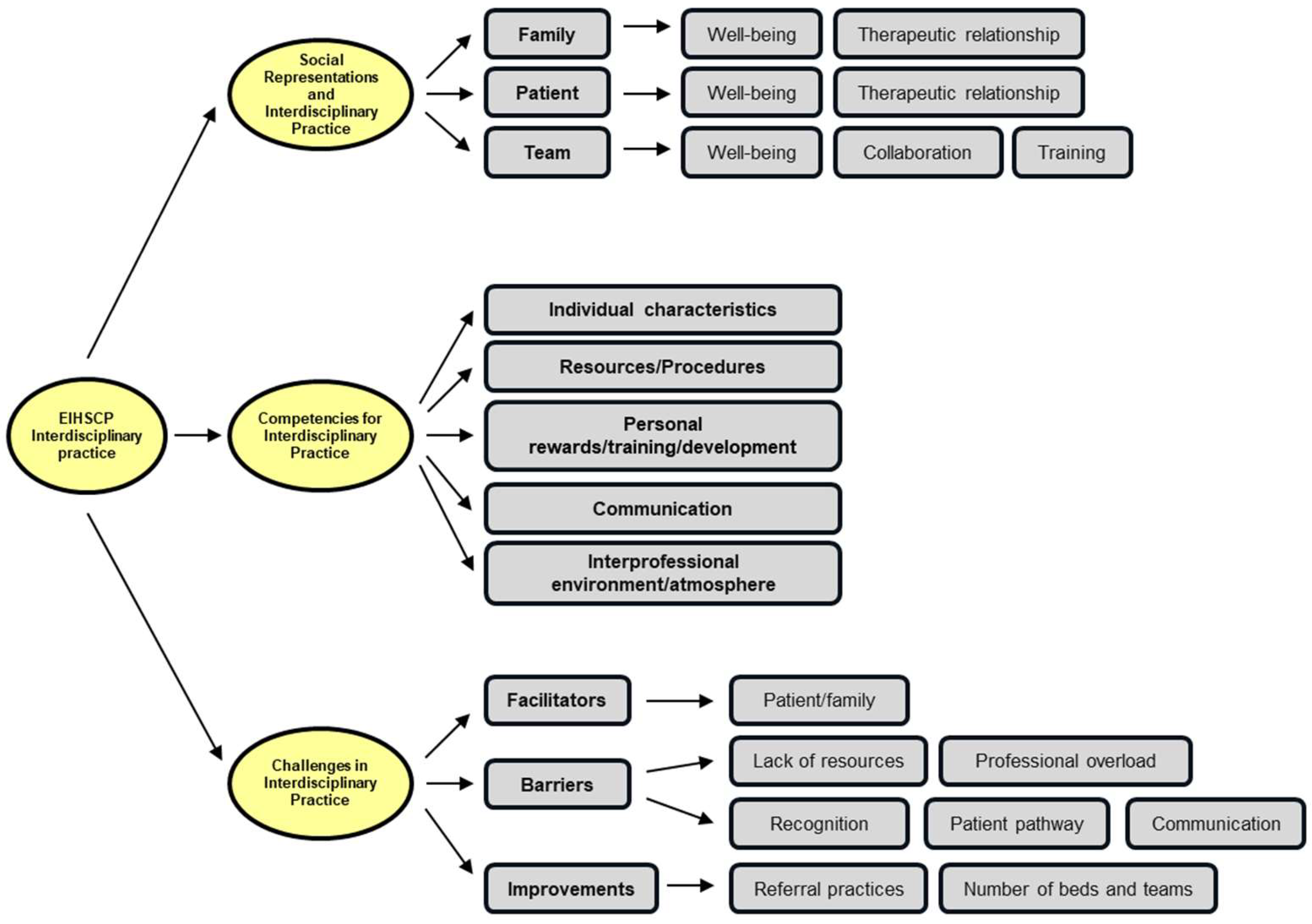

3.2. Study Results

3.2.1. Social Representations and Interdisciplinary Practice

- (a)

- Team

(P9: Physician) It means seeing various professional groups working together, where the sum of each one’s skills is greater than the individual parts (…) It is interesting and challenging to manage the boundaries between doctor and nurse (…) social worker, psychologist, and other necessary professions. Another role of the inter-hospital team within the hospital is to work in the wards, engaging with other professionals who receive support from the interdisciplinary team.

(P10: Social worker) The broad range of interdisciplinary knowledge enables more comprehensive care, promoting better quality of life, strengthening the professional-patient relationship, and reducing anxiety and stress.

- (b)

- Patient

(P1: Physician) The interdisciplinary approach, being comprehensive and holistic, addresses most of the needs of patients requiring palliative care (…) it provides some patients with a space for sharing and being heard, allowing for the assessment and prioritization of symptoms and the implementation of the most appropriate pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapeutic plan.

(P7: Nurse) The social aspect (…) the patient is discharged, and it is precisely important to also be able to communicate everything in the post-hospital discharge period.

- (c)

- Family

(P6: Psychologist) Collaboration among all is essential to ensuring the well-being of both the patient and their family, not in isolation, as a physician or psychologist alone, but through a comprehensive approach and effective team communication, which I believe is fundamental.

(P10: Social worker) The interdisciplinary approach in palliative care can have a positive impact on both the patient and their family, enhancing their overall well-being.

(P11: Nurse) Ongoing and active training is of utmost importance.

3.2.2. Competencies for Interdisciplinary Practice

- (a)

- Individual characteristics

(P1: Physician) Empathic capacity allows for appropriately adjusted compassionate attitudes without paternalism (…) Scientific rigor in both the working method and therapeutic strategies used (…) taking care of ourselves, knowing ourselves, and practicing self-care.

(P11: Nurse) Becoming aware of others’ suffering without judgment and with honesty (…) fostering attitudes that provide genuine support, ensuring that patients always feel they have a team that does not abandon them (…) a team that is present, available, and fully engaged.

(P2: Nurse) In effective interdisciplinary practice (…) addressing complex symptoms, guiding processes with ethical and cultural sensitivity, applying knowledge of emotional and spiritual support (…) and the ability to facilitate decision-making.

(P4: Psychologist) Maintaining compassion, humanity, and responsibility toward the patient, while acknowledging their concerns, vulnerabilities, and upholding our honesty.

(P10: Social worker) For effective interdisciplinary practice in palliative care, it is essential for the team to develop self-care and self-awareness skills. We can only care for others if we ourselves are well.

- (b)

- Resources and Procedures

(P10: Social worker) Interdisciplinary practices highlight the importance of family conferences, (…) the most relevant professionals for that situation should be present, or others should be called in, (…) for example, a nutritionist for a specific case.

(P8: Social worker) The approach in the first consultations, after assessing the needs, involves a socio-family diagnosis, engaging with the family and the patient, and explaining the available resources within the team (…) one of the professionals I immediately mention or inform as being available is the psychologist (…) seriously (…) it is an emotional trigger.

(P4: Psychologist) (…) it extends to the family, addressing concerns both in terms of what is happening and in the ongoing support and management of the patient (…) whether during hospitalization or solely through palliative care consultations (…) when the patient is at home and comes in for follow-ups. In bereavement support (…) which is a natural continuation and the final form of care we can offer to the family after the patient’s passing.

(P2: Nurse) Collaboration in the development of individualized care plans.

(P11: Nurse) Team meetings are also essential for jointly developing strategies (…) as well as (…) holding family conferences, coordinating care at different stages, aligning approaches, managing symptoms, providing emotional and psychological support, and establishing an advanced care plan.

- (c)

- Personal rewards/training/development

(P5: Nurse) Theoretical training is highly important.

(P3: Nurse) Developing self-care and self-awareness skills.

(P8: Social worker) It is obvious that someone with basic training does not have the same level of knowledge as someone with a postgraduate degree. However, the basics provided me with a foundation to realize that I needed more detailed information and deeper knowledge. I believe that the more information is available, the more it facilitates practice.

(P1: Physician) It supports me in scientific rigor, the working methodology, and therapeutic strategies (…) Palliative medicine provides valuable guidance, along with continuous updates in pharmacology and other non-pharmacological approaches.

(P12: Nurse) Knowledge and skills are essential for the symptomatic management of total pain, as well as for providing support and information about community resources.

(P8: Social worker) I must say that when I was invited to take part in palliative care training, I approached it without any particular expectations. I went without fully knowing what to expect and wasn’t particularly motivated at first. However, this field turned out to be a pleasant surprise (…) I’m grateful to be here, knowing that, in some way, we are able to make a difference in the lives of individuals, or even many.

- (d)

- Communication

(P2: Nurse) The ability to communicate effectively, work as a team, and collaborate with other healthcare professionals plays a key role in addressing complex symptoms.

(P1: Physician) Agile and assertive communication is crucial, free from paternalism (…) ensuring high-quality interactions within the team (…) and meaningful communication with patients and caregivers.

(P6: Psychologist) Communication is essential in this type of work and intervention (…) whether with colleagues, families, or patients, as it can sometimes become complex and delicate.

(P12: Nurse) Empathy, sincerity, adapted communication, and ethics.

- (e)

- Interprofessional environment/atmosphere

(P10: Social worker) Being able to put ourselves in another’s place, recognizing their suffering without judgment, and honestly fostering attitudes that provide meaningful support during this stage of their life, while ensuring they always feel surrounded by a team that is present, engaged, and never abandons them.

(P6: Psychologist) Beyond inpatient care and the support provided to hospitalized patients, the family is also included in this process. There is always a concern for their well-being, both in understanding what is happening and in fostering a climate of mutual support.

(P1: Physician) There must be a commitment to ethical conduct with a high level of maturity.

(P8: Social worker) Being a truly interdisciplinary team and trusting one another are serious challenges in the fast-paced environment of a hospital setting.

3.2.3. Challenges in Interdisciplinary Practice

- (a)

- Facilitators

(P8: Social worker) I believe we need to have enough humanity to adapt to other professionals, because it’s not just about each person’s profession, obviously, everyone has their own approach. We’re also talking about professionals’ personal beliefs, their temperament, and the degree of openness each one brings (…) it’s about adapting to one another’s temperament and working style, so that the team can function as seamlessly as possible, always in service of the patient.

(P3: Nurse) Well-structured teams (…) are characterized by mutual respect among team members.

(P2: Nurse) It greatly facilitates the active participation of patients and their families.

- (b)

- Barriers

(P2: Nurse) Resources are lacking.

(P9: Physician) Unfortunately, the barrier that everyone remembers is the insufficient availability of resources, both in terms of quantity and dedicated time. We still encounter situations where teams only have a psychologist for 10 h a week (…) and the same goes for social workers. It doesn’t work, even if those professionals are highly competent.

(P2: Nurse) In terms of barriers, the emotional exhaustion of palliative care professionals is highlighted, as well as the absence of recognition by professionals from other areas.

(P9: Physician) The professionals work under too much stress, under emotional overload (…) they are professionals who are permanently at risk of developing… well, situations of despair and so on.

(P1: Physician) Recognition of the specialty by hierarchical superiors in administration and the Ministry of Health, as well as by civil society. Recognition of the emotional and moral exhaustion of professionals in this field (…) Inadequate patient-to-healthcare professional ratios.

(P2: Nurse) Stigma associated with palliative care.

(P3: Nurse) Difficulty in demystifying who palliative care is intended for.

(P1: Physician) Recognition of the specialty by hierarchical superiors of the administration and the Ministry of Health, as well as by civil society.

(P3: Nurse) There is a lack of community-based services to ensure continuity of care for these patients and their families (…) which is crucial for the patient care pathway.

(P2: Nurse) Differences in values, perspectives, as well as cultural and linguistic barriers.

(P3: Nurse) Difficulty in communication with other teams.

- (c)

- Improvements

(P5: Nurse) Good practices to ensure timely referral (before the patient is admitted to the team and during discharge planning).

(P5: Nurse): The need to share and disseminate the core principles of palliative care.

(P9: Physician) There are many people experiencing collective anxieties within the general population. People are in the hospital, at home, wherever they choose (…) with the right to make that choice.

(P1: Physician) It is essential to promote health literacy in the field of palliative care (…) and to promote meaningful research in this area.

(P4: Psychologist) We have six temporary inpatient beds (…) which is not enough to meet the demand and needs of the population.

(P9: Physician) As long as a response is available, which is itself another limitation, the coordinating role of teams, both internally and with others, working together, is not always easy (…) it relies on highly intensive communication among all parties involved.

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PC | Palliative care |

| EIHSCPs | In-Hospital Palliative Care Support Teams |

| SNS | National Health System (Serviço Nacional de Saúde in Portuguese) |

Appendix A. Interview Guide

- Q1: What does interdisciplinary practice in palliative care within a hospital-based interdisciplinary team mean to you?

- Q2: In what ways does training in palliative care contribute to an interdisciplinary practice centered on the needs of patients and families within a hospital-based interdisciplinary team?

- Q3: How does interdisciplinary practice in palliative care influence the person receiving care, as well as the professional–patient relationship? Could you provide some examples?

- Q4: What knowledge and skills do you consider essential for effective interdisciplinary practice in palliative care?

- Q5: What interdisciplinary practices or activities do you engage in as part of your professional routine? Could you give some examples?

- Q6: What attitudes and values do you believe are necessary for interdisciplinary work in palliative care? Can you share any examples?

- Q7: What barriers do you identify to interdisciplinary practice in palliative care?

- Q8: What facilitators do you recognize in supporting interdisciplinary practice in palliative care?

- Q9: Is there anything else you would like to add regarding this topic?

References

- Ashcroft, R.; Bobbette, N.; Moodie, S.; Miller, J.; Adamson, K.; Smith, M.A.; Donnelly, C. Strengthening collaboration for interprofessional primary care teams: Insights and key learnings from six disciplinary perspectives. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2024, 37, S68–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radbruch, L.; De Lima, L.; Knaul, F.; Wenk, R.; Ali, Z.; Bhatnaghar, S.; Blanchard, C.; Bruera, E.; Buitrago, R.; Burla, C.; et al. Redefining Palliative Care-A New Consensus-Based Definition. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2020, 60, 754–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nancarrow, S.A.; Booth, A.; Ariss, S.; Smith, T.; Enderby, P.; Roots, A. Ten Principles of Good Interdisciplinary Teamwork. Hum. Resour. Health 2013, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuel, L.L.; Back, A.L. Palliative Care: Core Skills and Clinical Competencies, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Marston, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kesonen, P.; Salminen, L.; Kero, J.; Aappola, J.; Haavisto, E. An Integrative Review of Interprofessional Teamwork and Required Competence in Specialized Palliative Care. OMEGA-J. Death Dying 2024, 89, 1047–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, A.; Gonyea, J.; Wensley, T.; Nizza, M. High-quality patient-centered palliative care: Interprofessional team members’ perceptions of social workers’ roles and contribution. J. Interprof. Care 2024, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaseghi, F.; Yarmohammadian, M.H.; Raeisi, A. Interprofessional collaboration competencies in the health system: A systematic review. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2022, 27, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, M.; Encarnação, P.; Lumini, M.J. Cuidados paliativos, conforto e espiritualidade. In Autocuidado: Um Foco Central da Enfermagem; Escola Superior de Enfermagem do Porto, Ed.; Escola Superior de Enfermagem do Porto: Porto, Portugal, 2022; pp. 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Centro de Informação Regional das Nações Unidas para a Europa Ocidental. Guia Sobre Desenvolvimento Sustentável: 17 Objetivos para Transformar o Nosso Mundo. Available online: https://www.unric.org/pt (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Peeler, A.; Afolabi, O.; Harding, R. Palliative care is an overlooked global health priority: Improving access and tackling inequities in palliative care globally would help to reduce preventable suffering. BMJ 2024, 387, q2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, S.; Castillo, G.F.; Salas, E. How to overcome the nine most common teamwork barriers. Organ. Dyn. 2023, 52, 101006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xyrichis, A.; Rose, L. Interprofessional collaboration in the intensive care unit: Power sharing is key (but are we up to it?). Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2024, 80, 103536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presidência do Conselho de Ministros. (7 November 2023). Decreto-Lei n.º 102/2023: Procede à Criação, Com Natureza de Entidades Públicas Empresariais, de Unidades Locais de Saúde. Diário da República, 1.ª Série, N.º 215. Available online: https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/decreto-lei/102-2023-217386782 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Mollman, M.E.; Gierach, M.; Sedlacek, A. Palliative care knowledge following an interdisciplinary palliative care seminar. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2023, 41, 1002–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelas, M.L.V. Dor Total nos doentes com metastização óssea. Cad. Saúde 2008, 1, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamondi, C.; Larkin, P.; Payne, S. Core competencies in palliative care: An EAPC white paper on palliative care education—Part 1. Eur. J. Palliat. Care 2013, 20, 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Gamondi, C.; Larkin, P.; Payne, S. Core competencies in palliative care: An EAPC white paper on palliative care education—Part 2. Eur. J. Palliat. Care 2013, 20, 140–145. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, J.L.; Warren, J.S. The Case for Understanding Interdisciplinary Relationships in Health Care. Ochsner J. 2023, 23, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeck, J.; Meissner, F.; Ditscheid, B.; Krause, K.; Wedding, U.; Gebel, C.; Marschall, U.; Meyer, G.; Schneider, W.; Freytag, A. Utilization and quality of primary and specialized palliative homecare in nursing home residents vs. community dwellers: A claims data analysis. BMC Palliat. Care 2025, 24, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, J.H.; Yan, J.; Hoffman, S.J. A WHO report: Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. J. Allied Health 2010, 39, 196–197. [Google Scholar]

- Radbruch, L.; Foley, K.; De Lima, L.; Praill, D.; Fürst, C.J. The Budapest Commitments: Setting the goals a joint initiative by the European Association for Palliative Care, the International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care and Help the Hospices. Palliat. Med. 2007, 21, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radbruch, L.; Leget, C.; Bahr, P.; Müller-Busch, C.; Ellershaw, J.; de Conno, F.; Berghe, P.V. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: A white paper from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliat. Med. 2016, 30, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radbruch, L.; Payne, S. White paper on standards and norms for hospice and palliative care in Europe: Part 1. Eur. J. Palliat. Care 2009, 16, 278–289. [Google Scholar]

- Radbruch, L.; De Lima, L.; Lohmann, D.; Gwyther, E.; Payne, S. The Prague Charter: Urging governments to relieve suffering and ensure the right to palliative care. Palliat. Med. 2013, 27, 101–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. Available online: www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Twycross, R. Cuidados Paliativos, 2nd ed.; Climepsi Editores: Lisbon, Portugal, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lagerin, A.; Melin-Johansson, C.; Holmberg, B.; Godskesen, T.; Hjorth, E.; Junehag, L.; Lundh Hagelin, C.; Ozanne, A.; Sundelöf, J.; Udo, C. Interdisciplinary strategies for establishing a trusting relation as a pre-requisite for existential conversations in palliative care: A grounded theory study. BMC Palliat. Care 2025, 24, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- República Portuguesa. Relatório Sobre a Implementação da Agenda 2030 Para o Desenvolvimento Sustentável. 2017. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/14966Portugal(Portuguese)2.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Afonso, R.; Novo, A.; Martins, P. Fisioterapia em Cuidados Paliativos: Da Evidência à Prática; Lusodidacta: Sintra, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Comissão Nacional de Cuidados Paliativos. Serviços Integrados de Cuidados Paliativos nas Unidades Locais de Saúde; Direção Executiva do Serviço Nacional de Saúde: Lisboa, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, W.C.; Dias, A.A.S.; Amorim, J.; Silva, C.M.A.; Silva, J.A.; Justa, J.W.O.S.; Silva, G.B.; Santos, G.A.; Santos, E.O.; Oliveira, M.E.L.; et al. Cuidados paliativos: Abordagem multidisciplinar na promoção da qualidade de vida para pacientes em sofrimento. Braz. J. Implant. Health Sci. 2024, 6, 2735–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruera, E. Palliative Care Interdisciplinary Teams in Acute Care Hospitals and Cancer Centers: A Job for Sisyphus. J. Palliat. Med. 2024, 27, 976–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 4th ed.; National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care: Richmond, VA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McLaney, E.; Morassaei, S.; Hughes, L.; Davies, R.; Campbell, M.; Di Prospero, L. A framework for interprofessional team collaboration in a hospital setting: Advancing team competencies and behaviours. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2022, 35, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comissão Nacional de Cuidados Paliativos. Plano Estratégico para o Desenvolvimento dos Cuidados Paliativos em Portugal Continental: Biénio 2023–2024; Direção Executiva do Serviço Nacional de Saúde: Lisboa, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, D.V.L. A Fisioterapia em Cuidados Paliativos no Doente idoso em Contexto Domiciliário: Uma Revisão Scoping. Master’s Dissertation, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Lisbon, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual. Psychol. 2022, 9, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Ranfagni, S. A Step-by-Step Process of Thematic Analysis to Develop a Conceptual Model in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant | Age | Gender | Profession | Professional Experience (Years) | Professional Experience in PC (Years) | Advanced Training in PC | Other PC Training |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 41 | Male | Physician | 15 | 7 | Yes | No |

| P2 | 30 | Female | Nurse | 15 | 6 | No | Yes |

| P3 | 41 | Female | Nurse | 15 | 9 | Yes | Yes |

| P4 | 36 | Female | Psychologist | 11 | 6 | Yes | Yes |

| P5 | 38 | Female | Nurse | 15 | 9 | Yes | Yes |

| P6 | 28 | Female | Psychologist | 1 | 1 | No | Yes |

| P7 | 26 | Female | Nurse | 5 | 2 | No | No |

| P8 | 47 | Female | Social worker | 17 | 14 | No | Yes |

| P9 | 52 | Male | Physician | 30 | 23 | Yes | Yes |

| P10 | 39 | Male | Social worker | 15 | 13 | Yes | Yes |

| P11 | 41 | Female | Nurse | 15 | 14 | Yes | Yes |

| P12 | 47 | Female | Nurse | 17 | 7 | Yes | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cruz, C.; Querido, A.; Pedrosa, V.V. Perceptions and Practices of Interdisciplinary Action in an Intra-Hospital Support Team for Palliative Care: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101179

Cruz C, Querido A, Pedrosa VV. Perceptions and Practices of Interdisciplinary Action in an Intra-Hospital Support Team for Palliative Care: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101179

Chicago/Turabian StyleCruz, Célio, Ana Querido, and Vanda Varela Pedrosa. 2025. "Perceptions and Practices of Interdisciplinary Action in an Intra-Hospital Support Team for Palliative Care: A Qualitative Study" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101179

APA StyleCruz, C., Querido, A., & Pedrosa, V. V. (2025). Perceptions and Practices of Interdisciplinary Action in an Intra-Hospital Support Team for Palliative Care: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare, 13(10), 1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101179