Physical Activity Influences Negative Emotion Among College Students in China: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Psychological Resilience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Physical Activity Rating Scale

2.2.2. Depression-Anxiety-Stress Scale

2.2.3. Psychological Resilience

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Test for Common Method Variance

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

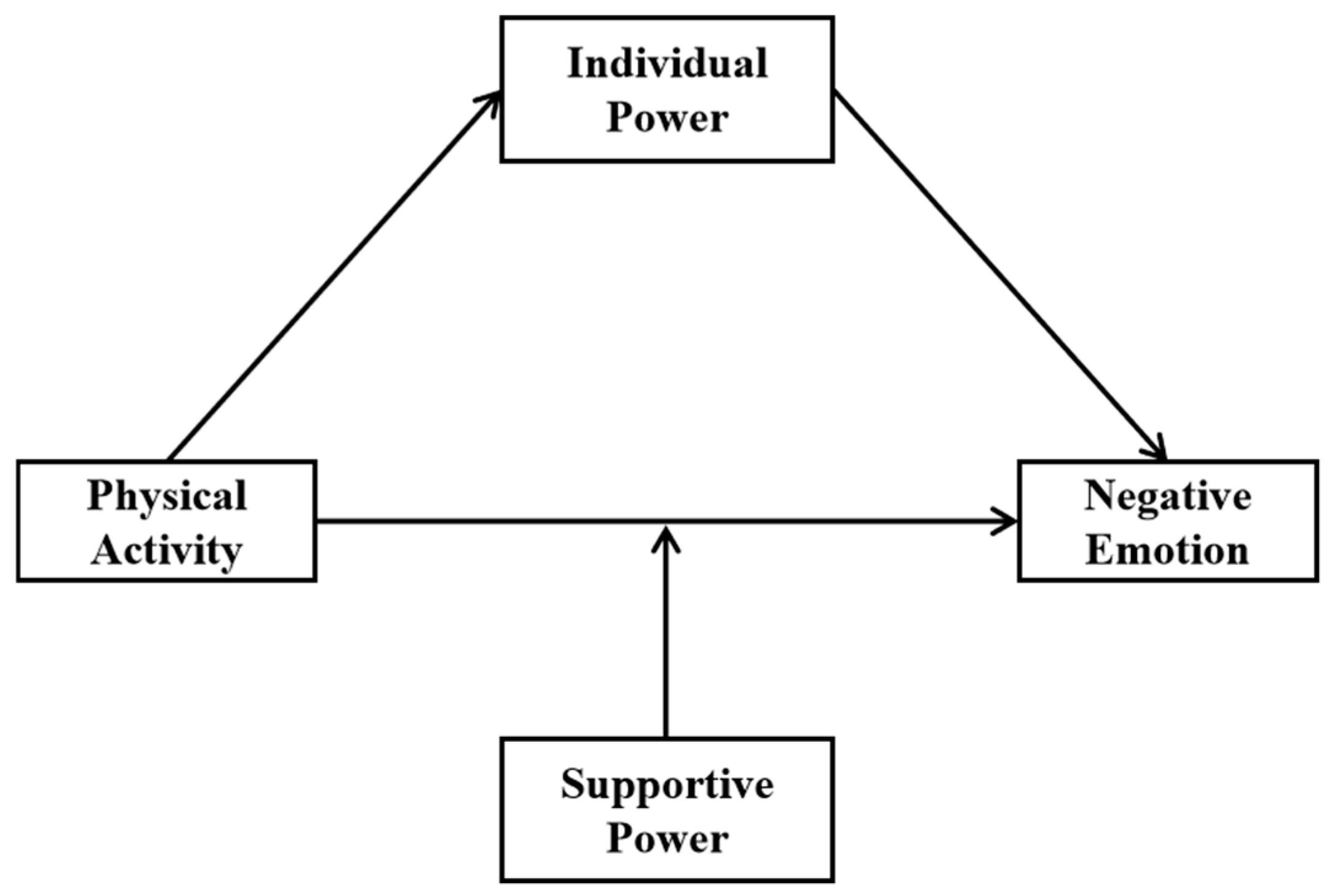

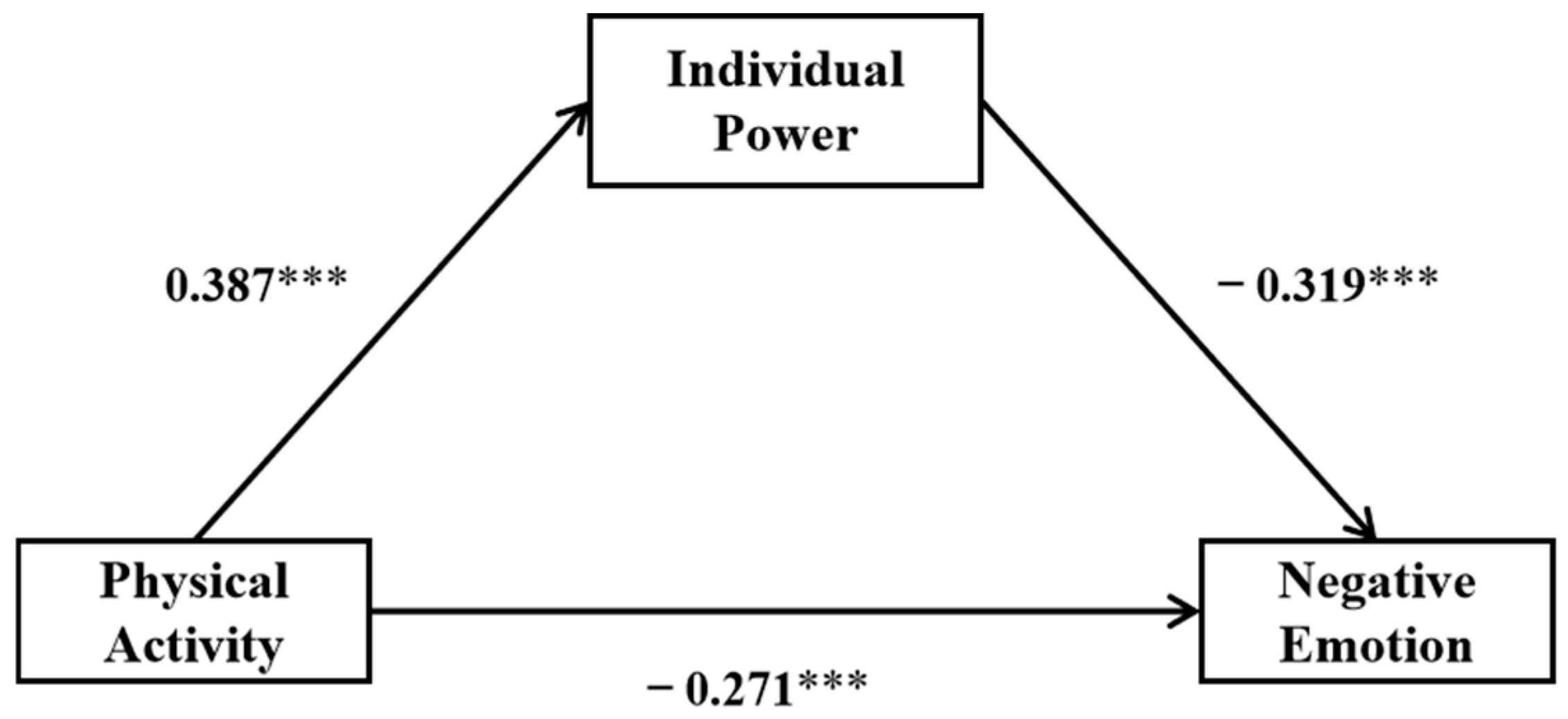

3.3. The Mediating Effect Analysis

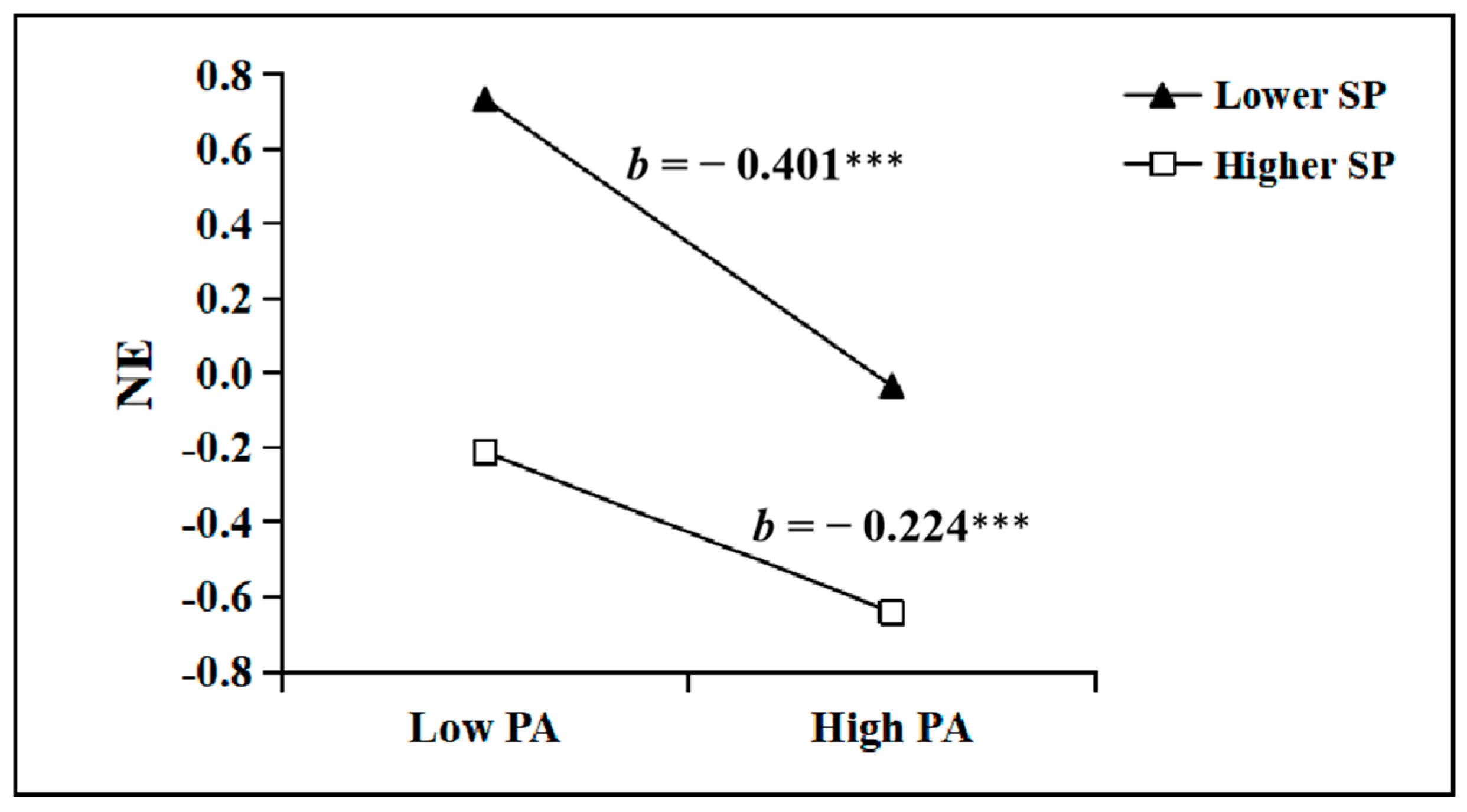

3.4. The Moderating Effect Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PA | Physical Activity |

| NE | Negative Emotion |

| IP | Individual Power |

| SP | Supportive Power |

References

- Auerbach, R.P.; Alonso, J.; Axinn, W.G.; Cuijpers, P.; Ebert, D.D.; Green, J.G.; Hwang, I.; Kessler, R.C.; Liu, H.; Mortier, P.; et al. Mental health disorders among college students in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol. Med. 2016, 47, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Carney, D.M.; Youn, S.J.; Janis, R.A.; Castonguay, L.G.; Hayes, J.A.; Locke, B.D. Are we in crisis? National mental health and treatment trends in college counseling centers. Psychol. Serv. 2017, 14, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F.; Liu, X.X.; Xu, X.; Wang, H.Y.; Yang, G. The effect of physical activity on sleep quality among Chinese college students: The chain mediating role of stress and smartphone addiction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, 17, 2135–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College Health Association. American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Executive Summary Spring 2019. Available online: https://www.acha.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/NCHA-II_SPRING_2019_US_REFERENCE_GROUP_EXECUTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Mahmoud, J.S.R.; Staten, R.T.; Hall, L.A.; Lennie, T.A. The relationship among young adult college students’ depression, anxiety, stress, demographics, life satisfaction, and coping styles. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 33, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selkie, E.M.; Kota, R.; Chan, Y.F.; Moreno, M. Cyberbullying, depression, and problem alcohol use in female college students: A multisite study. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Li, L.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, N.; Shangguan, R.; Yang, G. Effects of parental psychological control on mobile phone addiction among college students: The mediation of loneliness and the moderation of physical activity. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, C.; Jia, C.; Wang, S. Physical activity influences the mobile phone addiction among Chinese undergraduates: The moderating effect of exercise type. J. Behav. Addict. 2021, 10, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.F.; Xu, X.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, C.; Yang, G. The mediating effect of subjective well-being between physical activity and the internet addiction of college students in China during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1368199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.I.; Brice, S. The mood-enhancing benefits of exercise: Memory biases augment the effect. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, M.B.; Dunn, E.W.; Perrino, A.; Gillis, R.; Viel, S. The invisible benefits of exercise. Health Psychol. 2011, 30, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. Regular physical exercise and its association with depression: A population-based study. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 30, 114406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Hashim, S.B.; Huang, D.; Zhang, B. The effect of physical exercise on depression among college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ 2024, 16, 841160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, D.; Sarkar, M. Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. European J. Sport Sci. 2013, 18, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.Q.; Gan, Y.Q. Development and validation of the Adolescent Psychological Resilience Scale. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2008, 40, 902–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, K.; Gardner, J. The Development of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Wang, D.; Zhao, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L. The association between physical exercise behavior and psychological resilience of teenagers: An examination of the chain mediating effect. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, H.J.; Qin, Z.Z.; Tao, Y.N.; Ye, W.; Liu, R.Y. Effects of physical activity on depression, anxiety, and stress in college students: The chain-based mediating role of psychological resilience and coping styles. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1396795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.L. Questionnaire Statistical Analysis Practice—SPSS Operation and Application, 1st ed.; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 2010; pp. 218–220. [Google Scholar]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.Q.; Liu, S.J. The relationship between stress level and physical exercise for college students. Chin. Ment. Health J. 1994, 8, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X. The Relationship Between College Students’ Media Multitasking and Mental Health; Capital Normal University: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. J. Educ. Meas. 2013, 3, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinones, C.; Kakabadse, N.K. Self-concept clarity and compulsive internet use: The role of preference for virtual interactions and employment status in British and North-American samples. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvolensky, M.J.; Jardin, C.; Garey, L.; Robles, Z.; Sharp, C. Acculturative stress and experiential avoidance: Relations to depression, suicide, and anxiety symptoms among minority college students. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2016, 45, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, P.; Lei, S.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, Q.; Yang, H.; Zhou, N.; Zhang, G.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Associations between negative life events and anxiety, depressive, and stress symptoms: A cross-sectional study among Chinese male senior college students. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockwell, D.M.; Kimel, S.Y. A systematic review of first-generation college students’ mental health. J. Am. Coll. Health 2025, 73, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.Y.; Liu, X.X.; Xu, X.; He, B.C.; Wang, J.F.; Zuo, L.J.; Wang, H.Y.; Yang, G. Self-esteem mediates the relationship between physical activity and smartphone addiction of Chinese college students: A cross-sectional study. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1256743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garam, J.; Brenda, R.K.; Lee, Y. Effects of 12-week combined exercise program on self-efficacy, physical activity level, and health-related physical fitness of adults with intellectual disability. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2018, 14, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, A.L.; Trivedi, M.H.; Kampert, J.B.; Clark, C.G.; Chambliss, H.O. Exercise treatment for depression: Efficacy and dose-response. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wipfli, B.M.; Rethorst, C.D.; Landers, D.M. The anxiolytic effects of exercise: A meta-analysis of randomized trials and dose-response analysis. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2008, 30, 392–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, B.G.; Friedman, E.; Eaton, M. Comparison of jogging, the relaxation response, and group interaction for stress reduction. J. Sports Exerc. Psychol. 2008, 10, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Tan, G.X.; Li, Y.X.; Liu, H.Y.; Wang, S.T. Physical exercise decreases the mobile phone dependence of university students in China: The mediating role of self-control. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, P.; Li, S.; Liu, Q.; Yu, F.; Guo, Z.; Jia, S.; Wang, X. Canonical correlation analysis of depression and anxiety symptoms among college students and their relationship with physical activity. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebar, A.L.; Stanton, R.; Geard, D.; Short, C.E.; Duncan, M.J.; Vandelanotte, C. A meta-meta-analysis of the effect of physical activity on depression and anxiety in non-clinical adult populations. Health Psychol. Rev. 2015, 9, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orakcı, Ş.; Khalili, T. The impact of cognitive flexibility on prospective EFL teachers’ critical thinking disposition: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Cogn. Process. 2024, 34, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, C.E.; Mirowsky, J. Sex differences in the effect of education on depression: Resource multiplication or resource substitution? Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 1400–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, W.X. A review of psychological resilience. J. Shandong Norm. Univ. 2006, 51, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.-J.; Ji, Y.; Li, Y.-H.; Yuan, M.-Y.; Su, P.-Y. Childhood trauma and depression in college students: Mediating and moderating effects of psychological resilience. Asian J. Psychiatry 2021, 65, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, J.C.; Dobson, K.S.; Pusch, D. Childhood adversity and adult depression: The protective role of psychological resilience. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 64, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Yang, G.; Jiang, L.; Yang, R.; Ran, H.; Xie, F.; Xu, X.; Lu, J.; Xiao, Y. Resilience is inversely associated with self-harm behaviors among Chinese adolescents with childhood maltreatment. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.A.; Losee, J.E. The protective role of social network factors during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2023, 17, e12865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adobor, H. Supply chain resilience: A multi-level framework. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2018, 48, 533–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coteron, J.; Fernandez-Caballero, J.; Martin-Hoz, L.; Franco, E. The interplay of structuring and controlling teaching styles in physical education and its impact on students’ motivation and engagement. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, G.; Su, F. The effect of education model in physical education on student learning behavior. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 944507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, D.A.; Proctor, C.J.; Gaudet, D.J.; Canales, D. What is the mindful personality? Implications for physical and psychological health. Acta Psychol. 2022, 224, 103514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M (SD) | Age | Sex | PA | IP | SP | NE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 20.32 (1.47) | ―― | |||||

| 2. Sex | 0.53 (0.66) | 0.075 | ―― | ||||

| 3. PA | 16.08 (14.45) | 0.003 | −0.102 | ―― | |||

| 4. IP | 51.52 (7.95) | 0.046 | 0.025 | 0.387 *** | ―― | ||

| 5. SP | 41.12 (7.22) | 0.028 | 0.019 | 0.300 *** | 0.569 *** | ―― | |

| 6. NE | 31.11 (26.25) | −0.094 | 0.073 | −0.394 *** | −0.423 *** | −0.464 *** | ―― |

| Outcome | Predictors | R | R2 | F | Beta | t | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 0.387 | 0.150 | 104.545 *** | |||||

| IP | PA | 0.387 | 10.225 *** | 0.313 | 0.461 | |||

| Model 2 | 0.491 | 0.241 | 94.248 *** | |||||

| NE | PA | −0.271 | −6.971 *** | −0.347 | −0.194 | |||

| IP | −0.319 | −8.211 *** | −0.395 | −0.242 |

| Outcome | Predictors | R | R2 | F | Beta | t | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NE | 0.544 | 0.296 | 82.814 | |||||

| PA | −0.312 | −8.205 *** | −0.387 | −0.237 | ||||

| SP | −0.391 | −10.758 *** | −0.463 | −0.319 | ||||

| PA × SP | 0.089 | 2.752 ** | 0.025 | 0.152 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zuo, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yao, Y.; Yang, G. Physical Activity Influences Negative Emotion Among College Students in China: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Psychological Resilience. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101170

Zuo L, Wang Y, Wang J, Yao Y, Yang G. Physical Activity Influences Negative Emotion Among College Students in China: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Psychological Resilience. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101170

Chicago/Turabian StyleZuo, Lijun, Yao Wang, Jinfu Wang, Yidi Yao, and Guan Yang. 2025. "Physical Activity Influences Negative Emotion Among College Students in China: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Psychological Resilience" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101170

APA StyleZuo, L., Wang, Y., Wang, J., Yao, Y., & Yang, G. (2025). Physical Activity Influences Negative Emotion Among College Students in China: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Psychological Resilience. Healthcare, 13(10), 1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101170

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)