Predictors of Postpartum Depression in Korean Women: A National Cross-Sectional Study During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

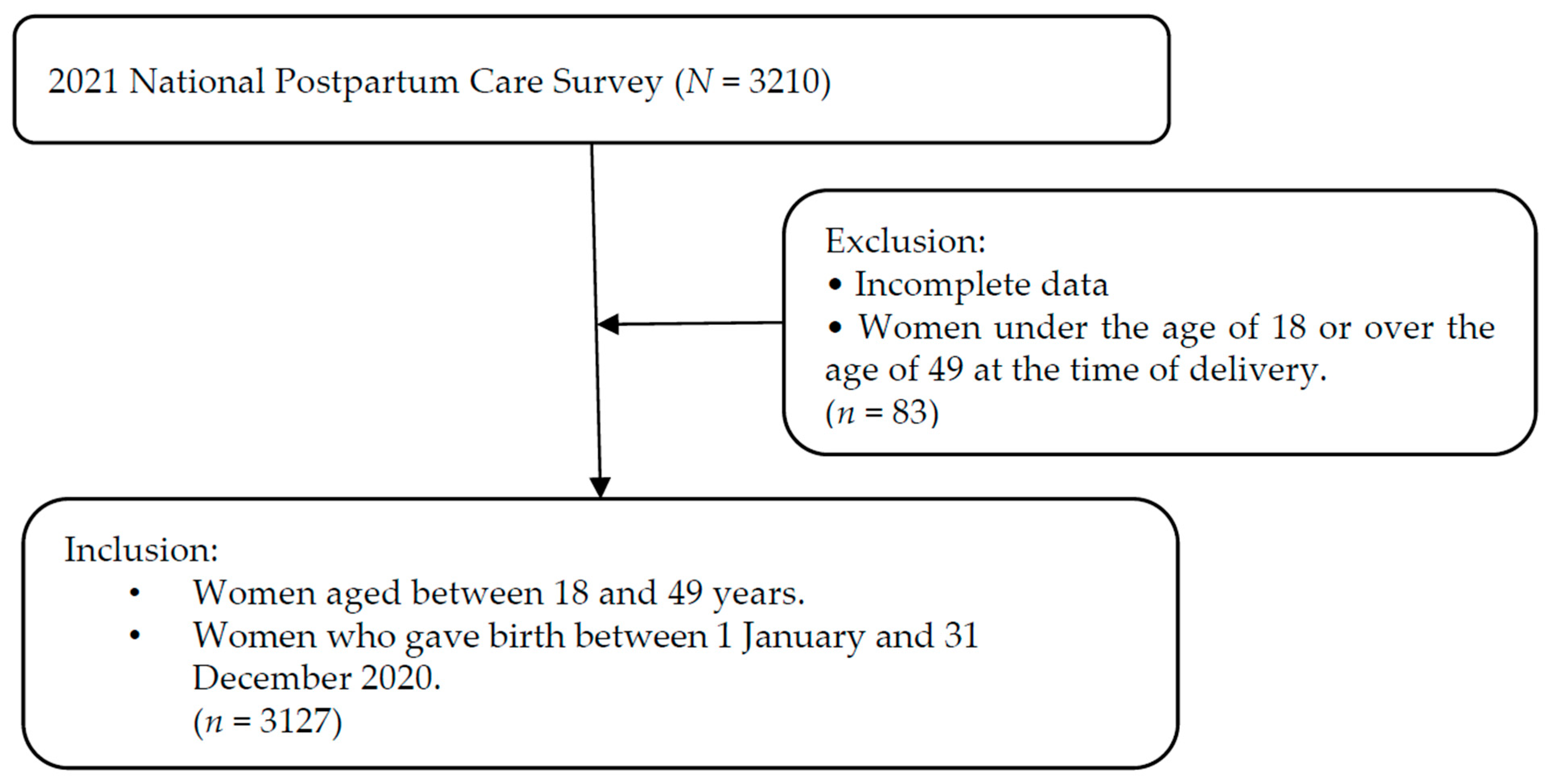

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Dependent Variable

- (1)

- Sociodemographic factors

- (2)

- Pregnancy and childbirth-related factors

2.2.2. Independent Variables

- (3)

- Infant health status

- (4)

- Paternal involvement in childcare

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Factors

3.2. Self-Reported Contributing Factors of Postpartum Depression and Paternal Involvement in Childcare

3.3. Factors Associated with Postpartum Depression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO Recommendations on Maternal and Newborn Care for a Positive Postnatal Experience. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240045989 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 727–729. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn-Holbrook, J.; Cornwell-Hinrichs, T.; Anaya, I. Economic and Health Predictors of National Postpartum Depression Prevalence: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression of 291 Studies From 56 Countries. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A.R.; Gordon, H.; Lindquist, A.; Walker, S.P.; Homer, C.S.E.; Middleton, A.; Cluver, C.A.; Tong, S.; Hastie, R. Prevalence of Perinatal Depression in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2023, 80, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.Y.; Khang, Y.-H.; June, K.J.; Cho, S.-H.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, Y.-M.; Cho, H.-J. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Maternal Depression among Women Who Participated in a Home Visitation Program in South Korea. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 1167–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guvenc, G.; Yesilcinar, İ.; Ozkececi, F.; Öksüz, E.; Ozkececi, C.F.; Konukbay, D.; Kok, G.; Karasahin, K.E. Anxiety, Depression, and Knowledge Level in Postpartum Women During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2021, 57, 1449–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacheva, K.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, M.F.; Gómez-Baya, D.; Domínguez-Salas, S.; Motrico, E. The Socio-Demographic Profile Associated With Perinatal Depression During the COVID-19 Era. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szurek-Cabanas, R.; Navarro-Carrillo, G.; Martínez-Sánchez, C.A.; Oyanedel, J.C.; Villalobos, D. Socioeconomic Status and Maternal Postpartum Depression: A PRISMA-Compliant Systematic Review. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 27339–27350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebi, A.; Kheiry, M.; Abdi, K.; Qomi, M.; Golitaleb, M. Postpartum Depression During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Umbrella Review and Meta-Analyses. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1393737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, D.C.; Tabb, K.M.; Tilea, A.; Hall, S.V.; Vance, A.; Patrick, S.W.; Schroeder, A.; Zivin, K. The Association Between NICU Admission and Mental Health Diagnoses Among Commercially Insured Postpartum Women in the US, 2010–2018. Children 2022, 9, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, Y.-L.; Qiu, D.; Xiao, S.-Y. Factors Influencing Paternal Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, H.A.; Einarson, A.; Taddio, A.; Koren, G.; Einarson, T.R. Prevalence of Depression During Pregnancy: Systematic Review. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 103, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bystrova, K.; Ivanova, V.; Edhborg, M.; Matthiesen, A.-S.; Ransjö-Arvidson, A.-B.; Mukhamedrakhimov, R.; Uvnäs-Moberg, K.; Widström, A.-M. Early Contact Versus Separation: Effects on Mother-Infant Interaction One Year Later. Birth 2009, 36, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, L.; Stanley, C.; Hooper, R.; King, F.; Fiori-Cowley, A. The Role of Infant Factors in Postnatal Depression and Mother-Infant Interactions. Dev. Med. Child Neurol 1996, 38, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, T. Postpartum Depression Effects on Early Interactions, Parenting, and Safety Practices: A Review. Infant Behav. Dev. 2010, 33, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, C.T. The Effects of Postpartum Depression on Maternal-Infant Interaction: A Meta-Analysis. Nurs. Res. 1995, 44, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Yoo, J.; Seol, K.O. The Mediating Effects of Role Orientation and the Meaning of Life on the Relationship between Mother’s Intensive Motherhood Ideology and Life Satisfaction: Role Orientation and Meaning of Life as Mediators, and Multi-group Analysis Based on Employment Status. J. Soc. Sci. 2023, 34, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.N.; Choi, S.Y. A Comparative Study of Postpartum Stress, Postpartum Depression, Postpartum Discomfort and Postpartum Activity, Between Women Who Used and Those Women Did Not Used Sanhujori Facilities. J. Korean Soc. Matern Child Health 2013, 17, 184–195. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, G. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Postpartum Depression in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 2943–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, C.S.; Kang, M.S.; Park, S.Y.; Choi, Y.R. Usefulness of Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for Postpartum Depression. Korean J. Perinatol. 2015, 26, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, W.; Xiong, J.; Zheng, X. Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated With Postpartum Depression During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, D.; Bohora, S.; Tripathy, S.; Thapa, P.; Sivakami, M. Perinatal Depression and Its Associated Risk Factors During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2024, 59, 1651–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L.K.; Kornfield, S.L.; Himes, M.M.; Forkpa, M.; Waller, R.; Njoroge, W.F.M.; Barzilay, R.; Chaiyachati, B.H.; Burris, H.H.; Duncan, A.F.; et al. The Impact of Postpartum Social Support on Postpartum Mental Health Outcomes During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2023, 26, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirbahaeddin, E.; Chreim, S. Transcending Technology Boundaries and Maintaining Sense of Community in Virtual Mental Health Peer Support: A Qualitative Study With Service Providers and Users. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshowkan, A.; Shdaifat, E.; Alnass, F.A.; Alqahtani, F.M.; AlOtaibi, N.G.; AlSaleh, N.S. Coping Strategies in Postpartum Women: Exploring the Influence of Demographic and Maternity Factors. BMC Womens Health 2023, 23, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khademi, K.; Kaveh, M.H. Social Support as a Coping Resource for Psychosocial Conditions in Postpartum Period: A Systematic Review and Logic Framework. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigod, S.N.; Tarasoff, L.A.; Bryja, B.; Dennis, C.-L.; Yudin, M.H.; Ross, L.E. Relation Between Place of Residence and Postpartum Depression. CMAJ 2013, 185, 1129–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, L.S.; Curran, L. “And You’re Telling Me Not To Stress?” A Grounded Theory Study of Postpartum Depression Symptoms Among Low-Income Mothers. Psychol. Women Q. 2009, 33, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Sasaki, S.; Hirota, Y. Employment, Income, and Education and Risk of Postpartum Depression: The Osaka Maternal and Child Health Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 130, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, H.D.; Darney, B.G.; Ahrens, K.; Burgess, A.; Jungbauer, R.M.; Cantor, A.; Atchison, C.; Eden, K.B.; Goueth, R.; Fu, R. Associations of Unintended Pregnancy With Maternal and Infant Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2022, 328, 1714–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, A.; Shraibman, L.; Yakupova, V. Long-Term Effects of Maternal Depression During Postpartum and Early Parenthood Period on Child Socioemotional Development. Children 2023, 10, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Bishai, D.; Minkovitz, C.S. Multiple Births Are a Risk Factor for Postpartum Maternal Depressive Symptoms. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highet, N.; McCarthy, M.J.; Lally, M.F. Multiple Birth Mental Health Outcomes Throughout Pregnancy, Delivery and Postnatally. Women Birth 2022, 35, 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.N.; Leistikow, N.; Smith, M.H.; Standeven, L.R. The Relationship Between Infant Feeding and Maternal Mental Health: Clinical Vignette. Adv. Psychiatry Behav. Health 2024, 4, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guide for Integration of Perinatal Mental Health in Maternal and Child Health Services; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240057142 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Zhang, Y.; Razza, R. Father Involvement, Couple Relationship Quality, and Maternal Postpartum Depression: The Role of Ethnicity Among Low-Income Families. Matern. Child Health J. 2022, 26, 1424–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pebryatie, E.; Paek, S.C.; Sherer, P.; Meemon, N. Associations Between Spousal Relationship, Husband Involvement, and Postpartum Depression Among Postpartum Mothers in West Java, Indonesia. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2022, 13, 21501319221088355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, I.; Mehendale, A.M.; Malhotra, R. Risk Factors of Postpartum Depression. Cureus 2022, 14, e30898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, P.; Li, M. The Association Between Paternal Childcare Involvement and Postpartum Depression and Anxiety Among Chinese Women-A Path Model Analysis. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2023, 26, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | N (%) | χ2 or t | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | No PPD (N = 2297) | PPD (N = 830) | ||||

| Region | Rural | 933 (29.8%) | 720 (31.3%) | 213 (25.7%) | 9.41 | 0.002 |

| Urban | 2194 (70.2%) | 1577 (68.7%) | 617 (74.3%) | |||

| Age | ≤24 years | 68 (2.2%) | 44 (1.9%) | 24 (2.9%) | 5.8 | 0.215 |

| 25–29 years | 422 (13.5%) | 301 (13.1%) | 121 (14.6%) | |||

| 30–34 years | 1248 (39.9%) | 938 (40.8%) | 310 (37.3%) | |||

| 35–39 years | 1072 (34.3%) | 780 (34.0%) | 292 (35.2%) | |||

| 40–49 years | 317 (10.1%) | 234 (10.2%) | 83 (10.0%) | |||

| Marital status | Single/unmarried | 27 (0.9%) | 13 (0.6%) | 14 (1.7%) | 8.95 | 0.003 |

| Married | 3100 (99.1%) | 2284 (99.4%) | 816 (98.3%) | |||

| Level of education | High school | 502 (16.1%) | 346 (15.1%) | 156 (18.8%) | 6.42 | 0.040 |

| College/University | 2327 (74.4%) | 1732 (75.4%) | 595 (71.7%) | |||

| Graduate school and above | 298 (9.5%) | 219 (9.5%) | 79 (9.5%) | |||

| Average monthly income (million KRW) | 1–2 | 155 (5%) | 111 (4.8%) | 44 (5.3%) | 6.58 | 0.160 |

| 3–4 | 1551 (49.6%) | 1112 (48.4%) | 439 (52.9%) | |||

| 5–6 | 921 (29.5%) | 696 (30.3%) | 225 (27.1%) | |||

| 7–8 | 351 (11.2%) | 262 (11.4%) | 89 (10.7%) | |||

| Greater than 8 | 149 (4.8%) | 116 (5.1%) | 33 (4.0%) | |||

| Pregnancy plan | Unplanned | 1125 (36.0%) | 790 (34.4%) | 335 (40.4%) | 9.43 | 0.002 |

| Planned | 2002 (64.0%) | 1507 (65.6%) | 495 (59.6%) | |||

| Parity | Primipara | 1715 (54.8%) | 1245 (54.2%) | 470 (56.6%) | 1.45 | 0.229 |

| Multipara | 1412 (45.2%) | 1052 (45.8%) | 360 (43.4%) | |||

| Depression in pregnancy | No depression | 1497 (47.9%) | 1390 (60.5%) | 107 (12.9%) | 554.08 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 1630 (52.1%) | 907 (39.5%) | 723 (87.1%) | |||

| Maternal health status | 3.14 ± 0.98 | 3.31 ± 0.93 | 2.66 ± 0.97 | 17.26 | <0.001 | |

| Duration of postpartum care | 30.15 ± 21.46 | 31.47 ± 21.23 | 26.5 ± 21.66 | 5.75 | <0.001 | |

| Number of infant care education sessions | 3.03 ± 2.38 | 3.12 ± 2.42 | 2.79 ± 2.25 | 3.58 | <0.001 | |

| Number of infant medical treatments | 1.03 ± 1.02 | 4.32 ± 0.78 | 4.09 ± 0.9 | 6.55 | <0.001 | |

| Perceived health of the infant | 4.26 ± 0.82 | 0.97 ± 0.98 | 1.2 ± 1.1 | −5.42 | <0.001 | |

| Paternal involvement in childcare | 27.52 ± 7.76 | 28.29 ± 7.27 | 25.36 ± 8.62 | 8.75 | <0.001 | |

| Self-Reported Contributing Factors of PPD | M ± SD |

|---|---|

| Burden of childcare | 1.76 ± 1.77 |

| Stress due to environmental changes | 1.70 ± 1.75 |

| Maternal physical health after childbirth | 1.67 ± 1.73 |

| Changes in body weight and physical appearance | 1.57 ± 1.67 |

| Lack of support from the spouse and family | 1.34 ± 1.49 |

| No specific reason | 1.29 ± 1.48 |

| Infant’s physical health condition | 1.08 ± 1.27 |

| Paternal involvement in childcare | M ± SD |

| Playing with the baby | 3.80 ± 1.16 |

| Changing diapers | 3.77 ± 1.22 |

| Soothing the baby when crying | 3.71 ± 1.19 |

| Performing household chores | 3.70 ± 1.25 |

| Bathing the baby | 3.69 ± 1.38 |

| Assisting with feeding | 3.50 ± 1.28 |

| Putting the baby to sleep | 3.45 ± 1.32 |

| Caring for the other children | 1.88 ± 2.15 |

| Factor | Model 1 | p-Value | Model 2 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | 95% CI | ||||

| Region | Urban (ref = rural) | 1.43 (1.4–1.47) | <0.001 | 1.29 (1.25–1.33) | <0.001 |

| Age (ref = ≤24 years) | ≤24 years | 0.67 (0.63–0.71) | <0.001 | 0.70 (0.66–0.75) | <0.001 |

| 30–34 years | 0.64 (0.61–0.68) | <0.001 | 0.63 (0.59–0.67) | <0.001 | |

| 35–39 years | 0.68 (0.64–0.71) | <0.001 | 0.66 (0.62–0.71) | <0.001 | |

| 40–49 years | 0.69 (0.65–0.73) | <0.001 | 0.62 (0.58–0.66) | <0.001 | |

| Marital status (ref = unmarried) | Married | 0.30 (0.28–0.33) | <0.001 | 0.65 (0.58–0.72) | <0.001 |

| Level of education (ref = high school graduate) | College/University | 0.81 (0.79–0.83) | <0.001 | 0.69 (0.67–0.71) | <0.001 |

| Graduate school and above | 0.76 (0.73–0.79) | <0.001 | 0.60 (0.58–0.63) | <0.001 | |

| Average monthly income (ref = 1–2 million KRW) | 3–4 | 1.19 (1.14–1.25) | <0.001 | 1.45 (1.38–1.53) | <0.001 |

| 5–6 | 1.02 (0.98–1.07) | 0.329 | 1.39 (1.32–1.47) | <0.001 | |

| 7–8 | 0.87 (0.82–0.91) | <0.001 | 1.20 (1.14–1.28) | <0.001 | |

| Greater than 8 | 1.02 (0.97–1.08) | 0.453 | 1.48 (1.38–1.58) | <0.001 | |

| Planned pregnancy (ref = unplanned) | 0.84 (0.83–0.86) | <0.001 | |||

| Multipara (ref = primipara) | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 0.012 | |||

| Depression in pregnancy (ref = no depression) | 8.65 (8.44–8.87) | <0.001 | |||

| Maternal health status (ref = Poor) | Moderate | 0.60 (0.59–0.62) | <0.001 | ||

| Good | 0.36 (0.35–0.37) | <0.001 | |||

| Duration of postpartum care | 0.99 (0.99–0.99) | <0.001 | |||

| Number of infant care education sessions | 0.97 (0.97–0.98) | <0.001 | |||

| Number of infant medical treatments | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | <0.001 | |||

| Perceived health of the infant (ref = Poor) | Moderate | 0.80 (0.76–0.85) | <0.001 | ||

| Good | 0.44 (0.42–0.46) | <0.001 | |||

| Paternal involvement in childcare | 0.97 (0.97–0.98) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cho, M.; Lee, M.H. Predictors of Postpartum Depression in Korean Women: A National Cross-Sectional Study During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101128

Cho M, Lee MH. Predictors of Postpartum Depression in Korean Women: A National Cross-Sectional Study During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101128

Chicago/Turabian StyleCho, Myongsun, and Meen Hye Lee. 2025. "Predictors of Postpartum Depression in Korean Women: A National Cross-Sectional Study During the COVID-19 Pandemic" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101128

APA StyleCho, M., & Lee, M. H. (2025). Predictors of Postpartum Depression in Korean Women: A National Cross-Sectional Study During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare, 13(10), 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101128