Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Therapy and Outcome of Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease at the Emergency Department

Abstract

1. Introduction

Goals of this Investigation

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population and Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Measurements

- Patient age and gender

- Date and time of arrival at the ED and leaving the ED (discharge or admission)

- Further management (discharge, admission to normal ward or ICU)

- Use of long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) at home

- Vital signs on admission (heart rate, blood pressure, blood gas analysis)

- Laboratory findings (inflammatory signs, renal function parameters)

- Respiratory therapy according to the WHO ordinal scale for COVID-19 clinical research:

- 0

- no clinical or virological evidence of infection

- 1

- ambulatory, no activity limitation

- 2

- ambulatory, activity limitation

- 3

- hospitalized, no oxygen therapy

- 4

- hospitalized, oxygen mask or nasal prongs

- 5

- hospitalized, noninvasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV) or high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC)

- 6

- hospitalized, intubation and invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV)

- 7

- hospitalized, IMV + additional support such as pressors or extracardiac membranous oxygenation (ECMO)

- 8

- death

- Chest X-ray findings (emphysema, pulmonary infiltrates)

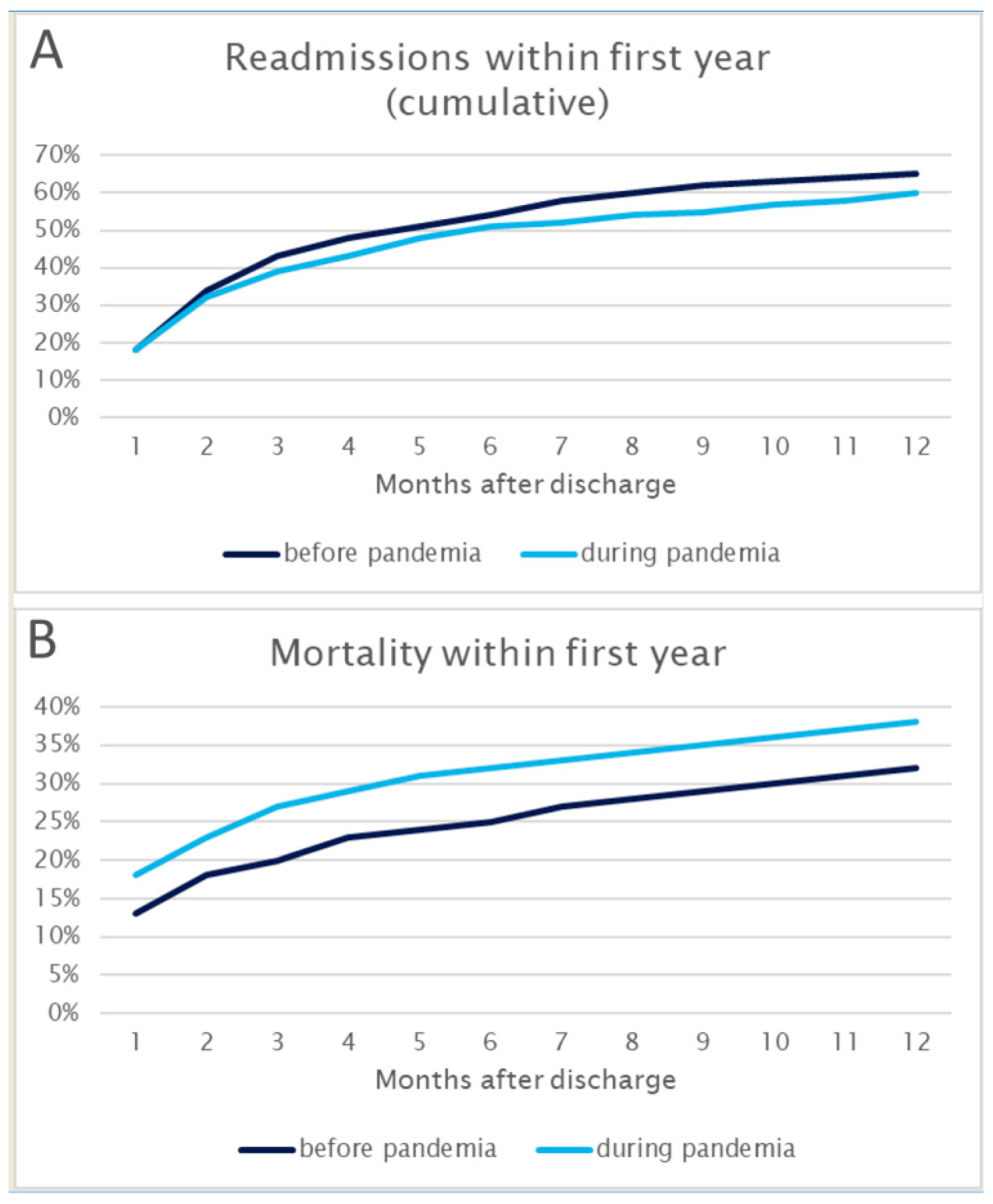

- Re-admission within one year

- Death within one year

2.4. Outcomes and Analysis

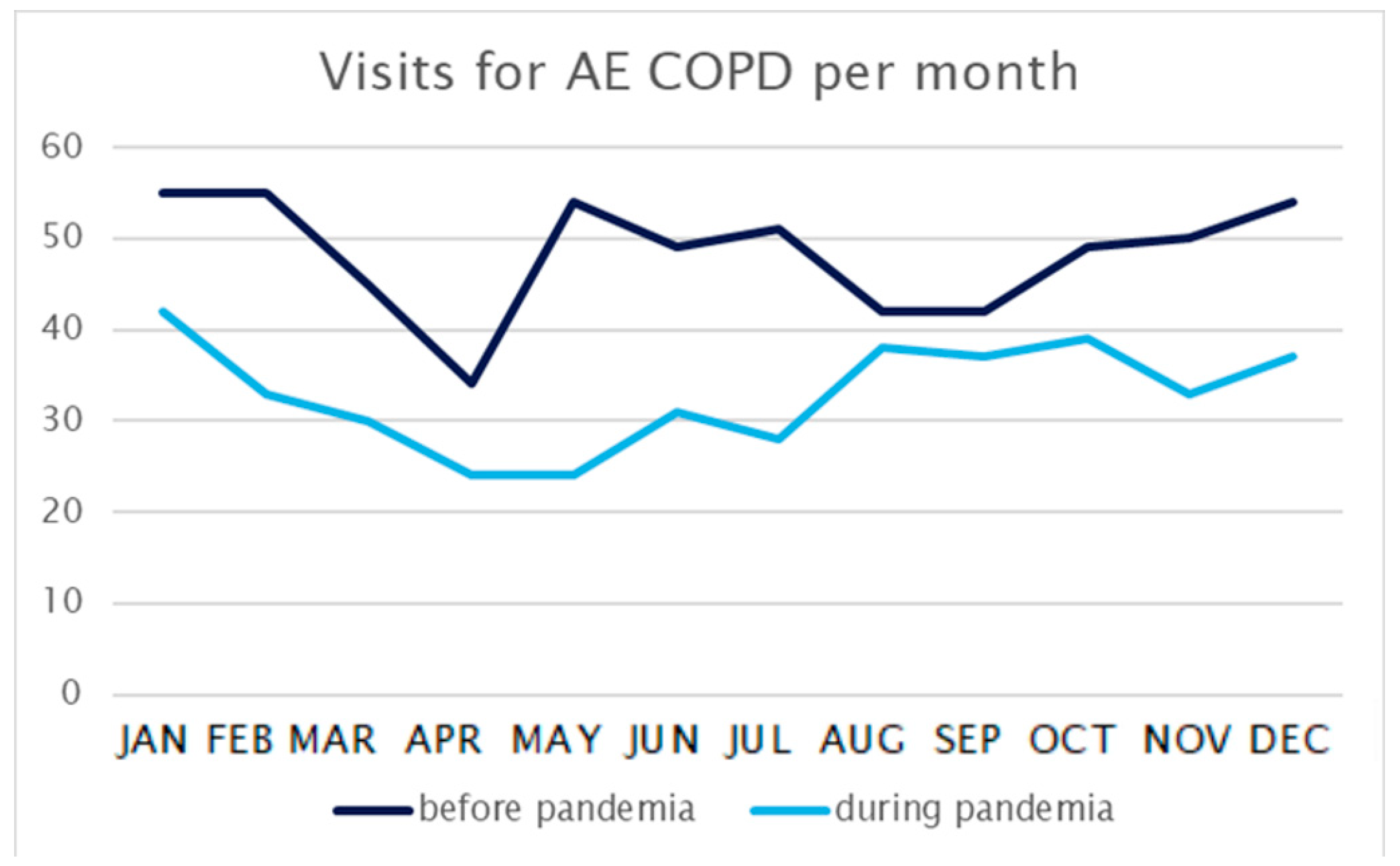

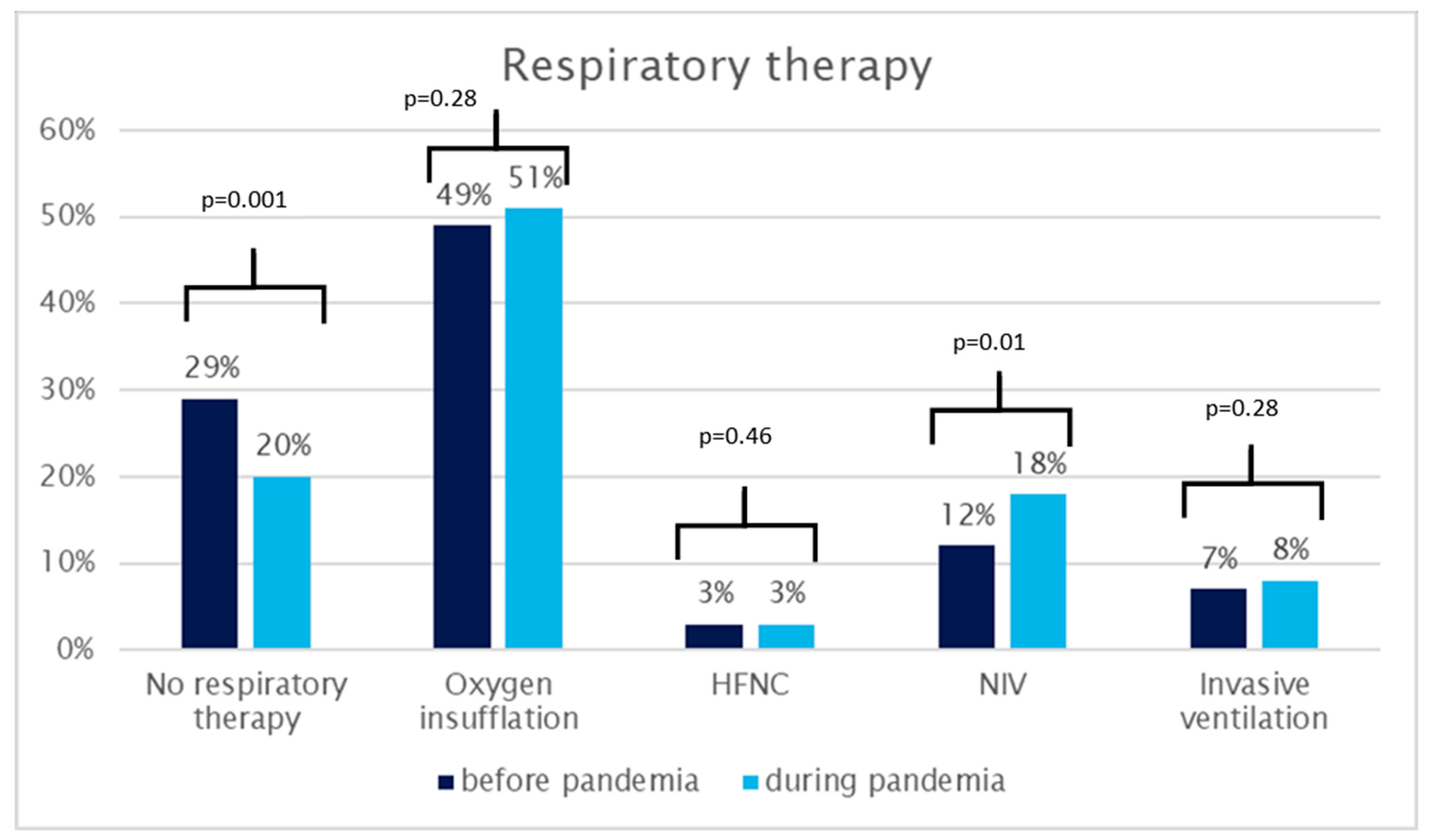

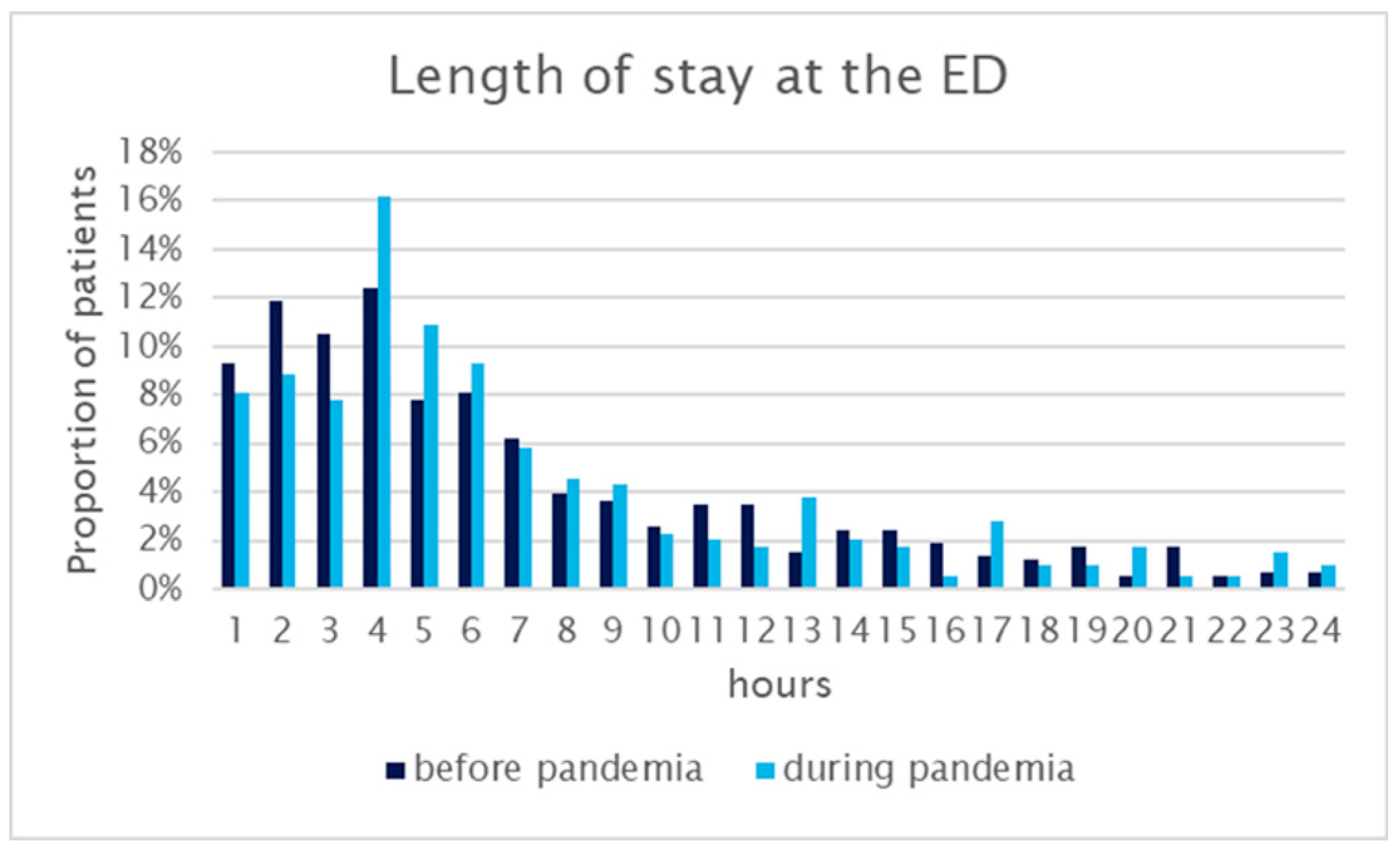

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Main Results

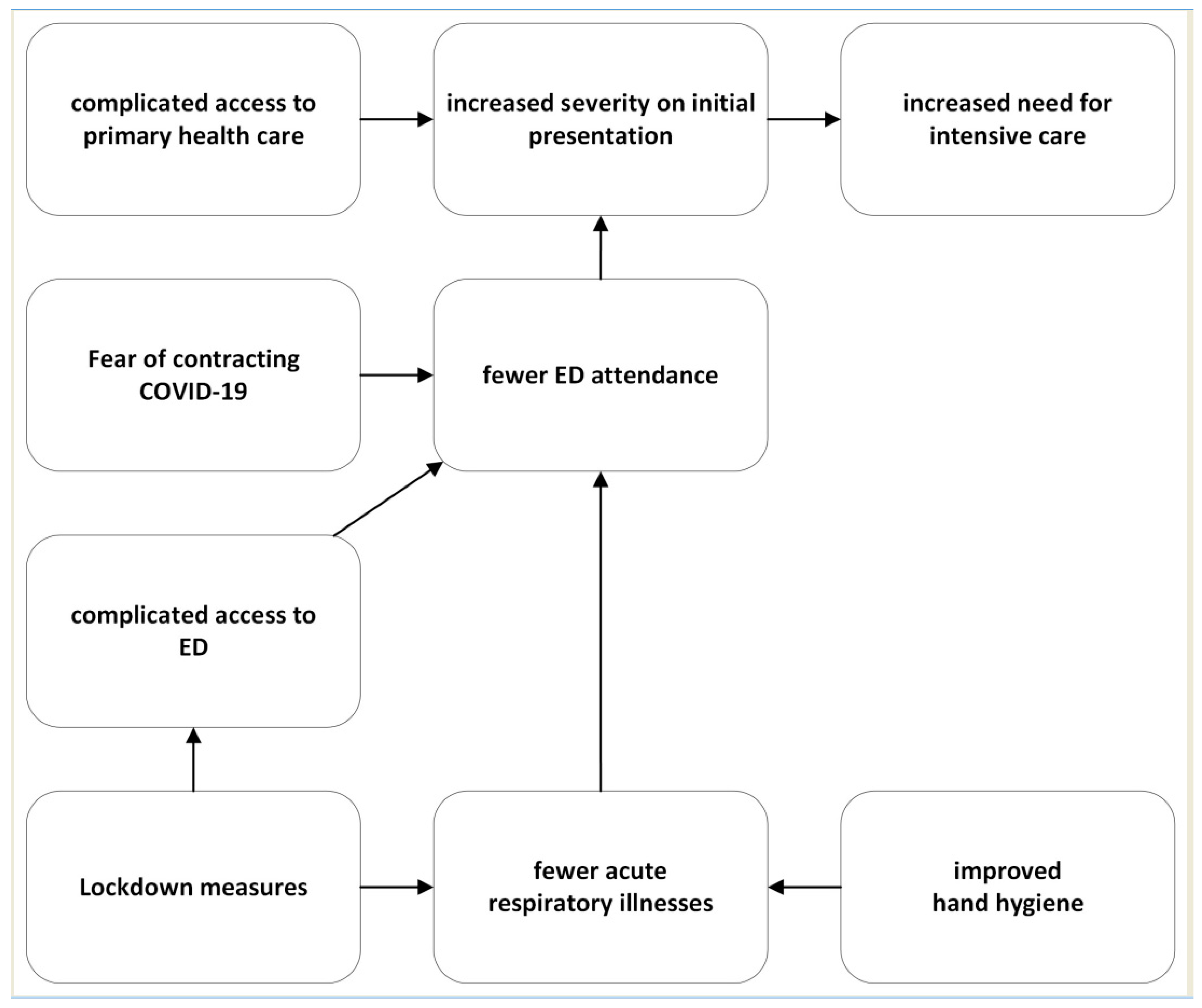

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rezwanul, R.; Gow, J.; Moloney, C.; King, A.; Keijzers, G.; Beccaria, G.; Mullens, A. Does distance to hospital affect emergency department presentations and hospital length of stay among COPD patients? Intern. Med. J. 2020, 52, 403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, O.; Gatheral, T.; Knight, J.; Giorgi, E. A modelling framework for developing early warning systems of COPD emergency admissions. Spat. Spatiotemporal. Epidemiol. 2021, 36, 100392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, R.O.; Shrestha, A.P.; Sonnenberg, T.; Mistry, J.; Shrestha, R.A.; MacKinney, T. Needs Assessment and Identification of the Multifaceted COPD Care Bundle in the Emergency Department of a Tertiary Hospital in Nepal. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2021, 16, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, J.M.; Niikura, M.; Yang Cheng, W.T.; Sin Don, D. COVID-19 and COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2002108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Meng, M.; Kumar, R.; Wu, Y.; Huang, J.; Lian, N.; Deng, Y.; Lin, S. The impact of COPD and smoking history on the severity of COVID-19: A systemic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 1915–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attaway, A.; Hatipoğlu, U. Management of patients with COPD during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paek, S.H.; Kim, D.K.; Lee, J.H.; Kwak, Y.H. The Impact of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Outbreak on Trends in Emergency Department Utilization Patterns. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 1576–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.-K.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Chung, Y.-T.; Lin, C.-C. The impact of the SARS outbreak on an urban emergency department in Taiwan. Med. Care 2005, 43, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenstein, J.; Chacko, J.; Ardolic, B.; Berwald, N. Impact of Hurricane Sandy on the Staten Island University Hospital Emergency Department. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2016, 31, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiber, M.; Lou, W.Y.W. Effect of the SARS outbreak on visits to a community hospital emergency department. CJEM 2006, 8, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-H.; Yen, D.H.-T.; Kao, W.-F.; Wang, L.-M.; Huang, C.-I.; Lee, C.-H. Declining emergency department visits and costs during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2006, 105, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.-A.; Lai, K.-H.; Chang, H.-T. Impact of a severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak in the emergency department: An experience in Taiwan. Emerg. Med. J. 2004, 21, 660–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benchimol, E.I.; Smeeth, L.; Guttmann, A.; Harron, K.; Moher, D.; Petersen, I.; Sørensen, H.T.; von Elm, E.; Langan, S.M. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wuerz, R.C.; Travers, D.; Gilboy, N.; Eitel, D.R.; Rosenau, A.; Yazhari, R. Implementation and refinement of the emergency severity index. Acad Emerg. Med. 2001, 8, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taffet, G.; Donohue, J.; Pablo, A. Considerations for managing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the elderly. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Butt, A.A.; Azad, A.M.; Kartha, A.B.; Masoodi, N.A.; Bertollini, R.; Abou-Samra, A.B. Volume and Acuity of Emergency Department Visits Prior To and After COVID-19. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 59, 730–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutovitz, S.; Pangia, J.; Finer, A.; Rymer, K.; Johnson, D. Emergency Department Utilization and Patient Outcomes during the COVID-19 Pandemic in America. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 60, 798–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heppner, Z.; Shreffler, J.; Polites, A.; Ross, A.; Thomas, J.J.; Huecker, M. COVID-19 and emergency department volume: The patients return but have different characteristics. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 45, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honeyford, K.; Coughlan, C.; Nijman, R.G.; Expert, P.; Burcea, G.; Maconochie, I.; Kinderlerer, A.; Cooke, G.S.; Costelloe, C.E. Changes in Emergency Department Activity and the First COVID-19 Lockdown: A Cross-sectional Study. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 22, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Before Pandemic (n = 580) | During Pandemic (n = 396) | Effect Size Differences (95% Cis) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years; median; IQR) | 70 (63–77) | 72 (65–79) | +1.5 (0.2–2.9) |

| Gender (male; n; %) | 295 (51%) | 218 (55%) | +4% (−2–11%) |

| Long-term oxygen therapy (n; %) | 177 (30%) | 132 (33%) | +3% (−3–9%) |

| Blood pressure systolic (mmHg) | 137 (56) | 140 (87) | +9 (−1–19) |

| Blood pressure diastolic (mmHg) | 80 (18) | 81 (18) | +1 (−1–4) |

| Heart rate (/min) | 97 (24) | 97 (25) | +/−0 (−3–4) |

| pCO2 (mmHg) | 50 (23) | 52 (23) | +4 (−0.5–8) |

| pH | 7.4 (0.1) | 7.3 (0.2) | −0.3 (−0.8–0.2) |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 1.9 (3.1) | 2.4 (2.2) | −0.2 (−0.3–0.7) |

| Leucocytes (G/L) | 11.1 (5.6) | 11.9 (5.9) | −4 (−4–12) |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 2.0 (7.5) | 1.9 (6.5) | +0.4 (−0.3–1.1) |

| Serum sodium (mmol/L) | 135 (11) | 136 (8) | +1 (−2–3) |

| Serum potassium (mmol/L) | 4.7 (0.6) | 4.4 (0.8) | −0.3 (−1.6–0.9) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.5 (3.7) | 1.4 (1.2) | −0.1 (−0.5–0.3) |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 25 (18) | 28 (22) | +3 (0.1–5.3) |

| Antibiotics (n; %) | 107 (18%) | 91 (23%) | +5% (−1–10%) |

| Emphysema (n; %) | 47 (8%) | 49 (12%) | +4% (0–8%) |

| Pulmonary venous congestions (n; %) | 82 (14%) | 96 (24%) | +10% (5–15%) |

| Atrial fibrillation (n; %) | 36 (6%) | 54 (14%) | +7% (4–11%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fuhrmann, V.; Wandl, B.; Laggner, A.N.; Roth, D. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Therapy and Outcome of Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease at the Emergency Department. Healthcare 2024, 12, 637. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12060637

Fuhrmann V, Wandl B, Laggner AN, Roth D. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Therapy and Outcome of Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease at the Emergency Department. Healthcare. 2024; 12(6):637. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12060637

Chicago/Turabian StyleFuhrmann, Verena, Bettina Wandl, Anton N. Laggner, and Dominik Roth. 2024. "Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Therapy and Outcome of Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease at the Emergency Department" Healthcare 12, no. 6: 637. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12060637

APA StyleFuhrmann, V., Wandl, B., Laggner, A. N., & Roth, D. (2024). Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Therapy and Outcome of Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease at the Emergency Department. Healthcare, 12(6), 637. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12060637