Digitalization of Activities of Daily Living and Its Influence on Social Participation for Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

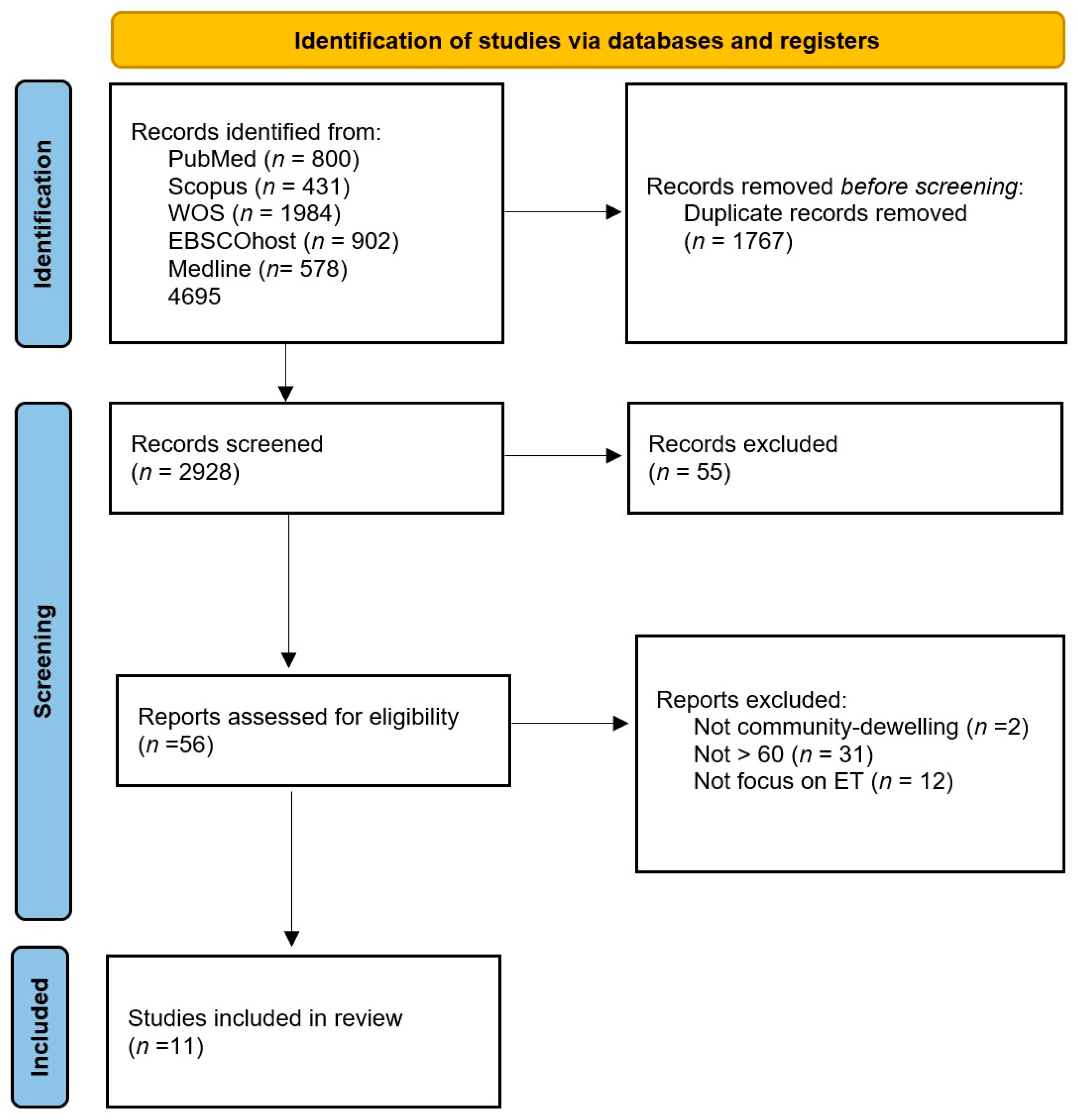

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Concepts

2.2.3. Contexts

2.2.4. Types of Sources

2.3. Study Selection, Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Population

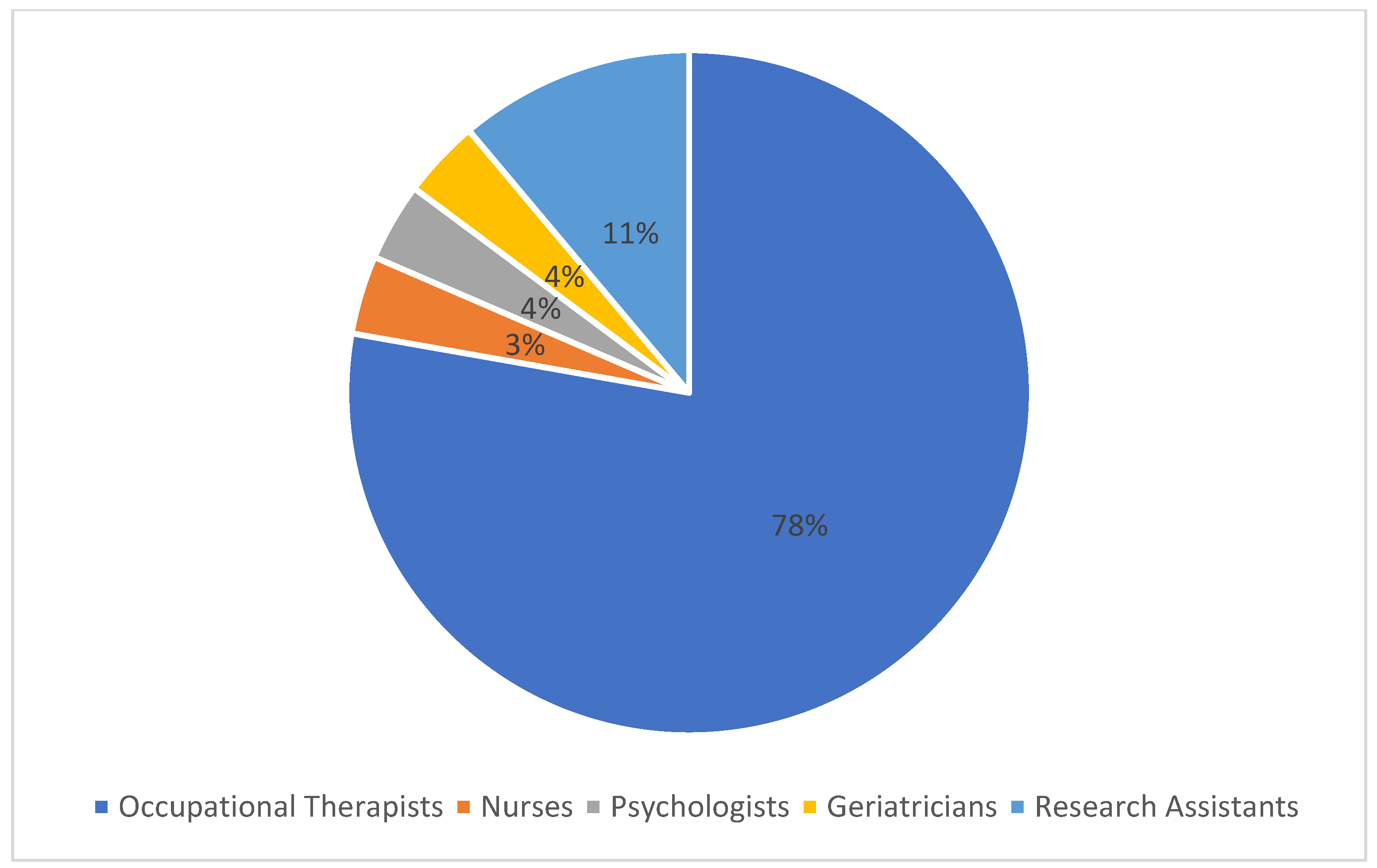

3.2. Methodology and Tools

3.3. Relevance and Self-Perceived Ability to Use Everyday Technologies

3.4. Engagement and Occupational Performance

3.5. Population with Mild Cognitive Impairment/Dementia

3.6. Occupational Therapy and Everyday Technology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pérez Díaz, J.; Abellán García, A.; Aceituno Nieto, P.; Ramiro Fariñas, D. Un perfil de las personas mayores en España 2020. Indicadores estadísticos básicos. Inf. Envejec. Red 2020, 25, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lafortune, G.; Balestat, G. Trends in Severe Disability among Elderly People: Assessing the Evidence in 12 OECD Countries and the Future Implications; OECD: Paris, France, 2007.

- Gaber, S.N.; Nygård, L.; Brorsson, A.; Kottorp, A.; Malinowsky, C. Everyday Technologies and Public Space Participation among People with and without Dementia. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 86, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, L.; Kottorp, A.; Winblad, B.; Nygård, L. Perceived Difficulty in Everyday Technology Use among Older Adults with or without Cognitive Deficits. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2009, 16, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AOTA. Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process—Fourth Edition. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 74, 7412410010p1–7412410010p87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nygård, L.; Starkhammar, S. The Use of Everyday Technology by People with Dementia Living Alone: Mapping out the Difficulties. Aging Ment. Health 2007, 11, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaber, S.N.; Nygård, L.; Brorsson, A.; Kottorp, A.; Charlesworth, G.; Wallcook, S.; Malinowsky, C. Social Participation in Relation to Technology Use and Social Deprivation: A Mixed Methods Study among Older People with and without Dementia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.L.; Canham, S.L.; Battersby, L.; Sixsmith, J.; Wada, M.; Sixsmith, A. Exploring Privilege in the Digital Divide: Implications for Theory, Policy, and Practice. Gerontologist 2019, 59, e1–e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallcook, S.; Malinowsky, C.; Nygård, L.; Charlesworth, G.; Lee, J.; Walsh, R.; Gaber, S.; Kottorp, A. The Perceived Challenge of Everyday Technologies in Sweden, the United States and England: Exploring Differential Item Functioning in the Everyday Technology Use Questionnaire. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 27, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsson, E.; Nygård, L.; Kottorp, A.; Olsson, C.B.; Malinowsky, C. The Use of Everyday Technology; a Comparison of Older Persons with Cognitive Impairments’ Self-Reports and Their Proxies’ Reports. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2021, 84, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborda Soriano, A.A.; Aliaga, A.C.; Vidal-Sánchez, M.I. Depopulation in Spain and Violation of Occupational Rights. J. Occup. Sci. 2021, 28, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.C. Mild Cognitive Impairment as a Diagnostic Entity. J. Intern. Med. 2004, 256, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voice, Agency, Empowerment—Handbook on Social Participation for Universal Health Coverage. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240027794 (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Hammell, K.W. Opportunities for Well-Being: The Right to Occupational Engagement. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2017, 84, E1–E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, P.-L.; Carrier, A.; Roy, V.; Levasseur, M. Occupational Therapists’ Contributions to Fostering Older Adults’ Social Participation: A Scoping Review. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 81, 427–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahpour, M.; Borell, L.; Luborsky, M.; Nygård, L. Leisure-Activity Participation to Prevent Later-Life Cognitive Decline: A Systematic Review. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2016, 23, 162–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsend, E.; Wilcock, A.A. Occupational Justice and Client-Centred Practice: A Dialogue in Progress. Can. J. Occup. Ther. Rev. Can. Ergother. 2004, 71, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köttl, H.; Gallistl, V.; Rohner, R.; Ayalon, L. “But at the Age of 85? Forget It!”: Internalized Ageism, a Barrier to Technology Use. J. Aging Stud. 2021, 59, 100971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chimento-Díaz, S.; Sánchez-García, P.; Franco-Antonio, C.; Santano-Mogena, E.; Espino-Tato, I.; Cordovilla-Guardia, S. Factors Associated with the Acceptance of New Technologies for Ageing in Place by People over 64 Years of Age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astasio-Picado, Á.; Cobos-Moreno, P.; Gómez-Martín, B.; Verdú-Garcés, L.; Zabala-Baños, M.d.C. Efficacy of Interventions Based on the Use of Information and Communication Technologies for the Promotion of Active Aging. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holthe, T.; Halvorsrud, L.; Karterud, D.; Hoel, K.-A.; Lund, A. Technology as Support for Everyday Living in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment in an Assisted Living Facility: A Systematic Literature Review. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=58789 (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Lawson, L.; Slight, S.; Mc Ardle, R.; Hughes, D.; Wilson, S. Digital Endpoints for Assessing Instrumental Activities of Daily Living in Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=326861 (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Wallcook, S.; Gaber, S. Barriers and Facilitators to the Use of Everyday Technology at Home and in Public Space Experienced by People Living with Dementia: A Systematic Review. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018110075 (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Khalil, H.; Larsen, P.; Marnie, C.; Pollock, D.; Tricco, A.C.; Munn, Z. Best Practice Guidance and Reporting Items for the Development of Scoping Review Protocols. JBI Evid. Synth. 2022, 20, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D.; Tricco, A.C.; Peters, M.D.J.; McInerney, P.A.; Khalil, H.; Godfrey, C.M.; Alexander, L.A.; Munn, Z. Methodological Quality, Guidance, and Tools in Scoping Reviews: A Scoping Review Protocol. JBI Evid. Synth. 2022, 20, 1098–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, R.; Drasga, R.; Lee, J.; Leggett, C.; Shapnick, H.; Kottorp, A. Activity Engagement and Everyday Technology Use among Older Adults in an Urban Area. Am. J. Occup. Ther. Off. Publ. Am. Occup. Ther. Assoc. 2018, 72, 7204195040p1–7204195040p7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, W.; Belchior, P.; Tomita, M.; Kemp, B. Barriers to the Use of Traditional Telephones by Older Adults with Chronic Health Conditions. OTJR-Occup. Particip. Health 2005, 25, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eek, M.; Wressle, E. Everyday Technology and 86-Year-Old Individuals in Sweden. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2011, 6, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, R.J.; Lee, J.; Drasga, R.M.; Leggett, C.S.; Shapnick, H.M.; Kottorp, A.B. Everyday Technology Use and Overall Needed Assistance to Function in the Home and Community among Urban Older Adults. J. Appl. Gerontol. Off. J. South. Gerontol. Soc. 2020, 39, 1115–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischl, C.; Lindelöf, N.; Lindgren, H.; Nilsson, I. Older Adults’ Perceptions of Contexts Surrounding Their Social Participation in a Digitalized Society-an Exploration in Rural Communities in Northern Sweden. Eur. J. Ageing 2020, 17, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeersch, S.; Gorus, E.; Cornelis, E.; De Vriendt, P. An Explorative Study of the Relationship between Functional and Cognitive Decline in Older Persons with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 78, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryd, C.; Nygård, L.; Malinowsky, C.; Öhman, A.; Kottorp, A. Associations between Performance of Activities of Daily Living and Everyday Technology Use among Older Adults with Mild Stage Alzheimer’s Disease or Mild Cognitive Impairment. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 22, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartels, S.L.; Assander, S.; Patomella, A.-H.; Jamnadas-Khoda, J.; Malinowsky, C. Do You Observe What I Perceive? The Relationship between Two Perspectives on the Ability of People with Cognitive Impairments to Use Everyday Technology. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 1295–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedman, A.; Lindqvist, E.; Nygård, L. How Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment Relate to Technology as Part of Present and Future Everyday Life: A Qualitative Study. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryd, C.; Malinowsky, C.; Öhman, A.; Kottorp, A.; Nygård, L. Older Adults’ Experiences of Daily Life Occupations as Everyday Technology Changes. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 81, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heatwole Shank, K.S. “You Know, I Swipe My Card and Hope for the Best”: Technology and Cognition as Dual Landscapes of Change. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2022, 8, 23337214221128402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedman, A.; Nygård, L.; Kottorp, A. Everyday Technology Use Related to Activity Involvement among People in Cognitive Decline. Am. J. Occup. Ther. Off. Publ. Am. Occup. Ther. Assoc. 2017, 71, 7105190040p1–7105190040p8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedman, A.; Nygård, L.; Almkvist, O.; Kottorp, A. Amount and Type of Everyday Technology Use over Time in Older Adults with Cognitive Impairment. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 22, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patomella, A.-H.; Lovarini, M.; Lindqvist, E.; Kottorp, A.; Nygård, L. Technology Use to Improve Everyday Occupations in Older Persons with Mild Dementia or Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Scoping Review. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 81, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepens Niemiec, S.L.; Lee, E.; Saunders, R.; Wagas, R.; Wu, S. Technology for Activity Participation in Older People with Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia: Expert Perspectives and a Scoping Review. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2023, 18, 1555–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygård, L. Instrumental Activities of Daily Living: A Stepping-Stone towards Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis in Subjects with Mild Cognitive Impairment? Acta Neurol. Scand. Suppl. 2003, 179, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study (Year), Country | Aim | Population | Methodology/Tool | Technology Type | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walsh et al. (2018), USA [28] | Investigate associations among activity engagement (AE), number of available and relevant everyday technologies, ability to use everyday technologies and cognitive status. | n = 110 adults in an urban area | Observational study: Everyday Technology Use Questionnaire (ETUQ), Frenchay Activities Index (FAI), the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). | ET (88 items): Instrumental activities of daily living as well as in social and community activities. | The number of available and relevant everyday technologies was significantly different (p < 0.001) among groups that varied in level of AE. The ability to use ETs did not significantly differ among groups. Cognitive status did not explain level of AE when the number of available and relevant ETs was considered. | Increasing the accessibility of available and relevant ETs among older adults in an urban area may increase activity engagement. |

| Mann et al. (2005), USA [29] | Explore the needs and barriers of the use of the telephone and its features from the perspective of older adults. | n = 609 | Observational study: questionnaire that included yes or no, multiple-choice, open-ended and Likert scale questions and answers. | Traditional (telephone) | The most common reasons for using a telephone were social contact (98.2%), setting up medical appointments (90.3%), refilling prescriptions (81.2%), business (55.6%) and calling for help/assistance (49.0%). | Therapists should be prepared to address issues related to telephone placement and wiring, furniture placement and provision of information about cost and telephone features that address specific impairments. Therapists can also address issues about background noise, telephone maintenance, nuisance calls and special services |

| Eek and Wressle (2011), Sweden [30] | Investigate the presence of ET use in the homes of 86-year-old people in Sweden as well as benefits or perceived problems and needs for other technology. Another aim was to study users ‘perceptions of technical development and its influence on their lives. | Total n = 274 | Quantitative and qualitative design: Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), ETUQ | Everyday technologies | Watching TV was important. This medium, combined with reading newspapers, was important for obtaining news. The most common problems in the use of ETs were related to visual or hearing impairments or operating difficulties. Regarding access to a computer, cognitive impairment impeded ET use and increased perceived problems. | Occupational therapists need to address the area of ET to facilitate occupational performance and increased participation in society. |

| Walsh et al. (2020), USA [31] | Investigate whether assessing use of ETs enhanced predictions of overall needed assistance among urban older adults. | n = 108 | Quantitative, cross-sectional study: ETUQ, MOCA, the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS) | Everyday technologies | Cognitive status was a significant predictor of minimal or moderate needed assistance. The number of available and relevant technologies that were used became the most significant predictor of minimal or moderate needed assistance. | As urban older adults must increasingly use everyday technologies to engage in valued activities, health professionals play a role in screening ET use to reduce overall needed assistance. |

| Fischl et al. (2020), Sweden [32] | Explore older adults’ perceptions about contexts surrounding their social participation in a digital society. | n = 18 older adults from rural communities | Qualitative design: Focus group interviews | Access to and use of digital technologies (laptop computers, printers, smart telephones, tablets) | The authors found a juxtaposition between offline social networks and the expanded opportunities that digitalization brings for social participation. Participants revealed reduced opportunities for social interaction, which they ascribed to prioritizing home activities, dwindling social groups and increasing computerized access to services. Concomitantly, participants acknowledged increasing possibilities to use digital technologies in daily life. | Cocreating usable digitalized services and facilitating satisfactory use of digital technologies could support older adults’ social participation through activities that they find relevant in their lives; subsequently, this may enable them to live at home for longer. |

| Study (Year), Country | Aim | Population | Methodology/Tool | Technology Type | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vermeersch et al. (2015), Belgium [33] | Investigate the relationship between functional decline in those three a-ADLs (advanced activities of daily living) and cognitive decline in persons with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), persons with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and cognitively healthy controls. | 45 MCI, 48 AD, 50 cognitively healthy controls | Observational study. MMSE. Cambridge Cognitive Examination (CAMCOG). a-ADL (ET), a-ADL (DRIVING), a-ADL (ECONOMY). | Everyday technology, driving a vehicle, performing complex economic activities | The cognitive disability index for performing complex economic activities and the cognitive disability index for the three advanced activities of daily living domains together differed significantly between the three groups. For the whole sample, the advanced activity of daily living cognitive disability indices correlated strongly with the cognitive measures. Within each separate group, few correlations were found. | The value of assessment of advanced activities of daily living in early cognitive decline is emphasized. Functional impairment in certain a-ADLs can be an early marker for cognitive decline, and evaluation of the performance of complex economic activities can thereby be of great importance. |

| Ryd et al. (2015), Sweden [34] | Explore associations between ADL performance and perceived ability to use ET among older adults with mild-stage AD and MCI. ADL motor and process ability as well as ability to use ET were also compared between the groups. | AD (n = 39) MCI (n = 28) | Observational study Short version ETUQ (S-ETUQ) AMPS. | Everyday technology. ADL motor and process performance ability | Significant correlations were found between ADL process ability and ET use in both groups (Rs = 0.44 and 0.32, p < 0.05); however, for ADL motor ability and ET use, correlations were found only in the MCI group (Rs = 0.51, p < 0.01). The MCI group had significantly higher measures of ADL process ability (p < 0.001) and ET use (p < 0.05). | ADL performance ability and perceived ability to use ET are important to consider in evaluations of older adults with cognitive impairments. Group differences indicate that measures of ADL performance ability and ET use are sensitive enough to discriminate the MCI group from the AD group with individually overlapping measures. |

| Bartels et al. (2020), Sweden [35] | Evaluate the relationship between the self-perceived ability to use ET and observable performance of self-chosen and familiar (but challenging) ETs in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia. | Total n = 79 MCI (n = 41) Dementia (n = 38) | Observational study FAI MMSE S-ETUQ (33 items). Management of Everyday Technology Assessment (META). | Everyday technologies | In the dementia group, self-perceived report and observational scores correlated at a medium significance level (Rs¼0.44, p¼0.006). In the MCI group, no significant correlation was found. | Benefits of combining the S-ETUQ and META to gain knowledge about the individual’s situation were found. The findings of this study suggest the ability of older adults with cognitive impairments to use ETs can be depicted with self-perceived reports as well as with observations. |

| Hedman et al. (2016), Sweden [36] | Explore how persons with mild cognitive impairment relate to technology as a part of and as potential support in everyday life—both present and future. | n = 6 | Qualitative in-depth interviews. | Everyday technologies | There are three different ways of relating to existing and potential future technology in everyday occupations as a continuum of downsizing, retaining and updating. | Persons with MCI may relate to technology in various ways to meet the needs of downsizing, which simultaneously may involve downsizing, retaining and updating technology use. |

| Ryd et al. (2018), Sweden [37] | Explore what can drive and hinder the incorporation of ET into occupations and how new technology affects occupational engagement and performance among older adults. | n = 11 | Explorative interview, semistructured S-ETUQ, FAI. | Everyday technologies | The degree of match of the participants’ perceptions of occupational purposes, the type of technology users they strived to be and their need to feel secure and in control in the occupation was essential for the choice of incorporating a new technology and for satisfaction with the altered occupations. | Occupational engagement and performance in relation to technology use can be facilitated, which is useful knowledge for stakeholders who are developing and implementing new technology as well as those who encounter older adults with the needs or desire to use technology in their daily occupations. |

| Heatwole Shank (2022), USA [38] | Explore the nature of out-of-home experience with technology in the context of daily life situations for community-dwelling older adults with MCI. | n = 10 | Qualitative design go-along interview. | Everyday technologies | The individuals in this study regularly engaged in activities in the community, despite experiencing changes in their cognitive abilities. Observations and accounts of quotidian experiences showed the significant (yet sometimes tacit or hidden) role of technology in daily life that shaped these patterns of engagement. Key findings include the four modes of experiencing this technology landscape, whereby technology served to enable, facilitate, impede and outright constrict participation for this population. | In representing the experiences of older adults as technology users, social discourse and media have a tendency towards caricature: technology is seen as a frustration and barrier for older adults. Conversely, the growing gerotechnology industry capitalizes on the image of technological innovations as the solution to many of the common challenges associated with ageing in place. |

| Author | Total Sample | Cognitively Healthy Control/ MCI 1 | MCI 2 SCI 3 | Alzheimer’s Disease/Mild-Stage Dementia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vermeersch et al. [33] | 143 | 50 | 45 | 48 |

| Ryd et al. [34] | 67 | 28 | 39 | |

| Bartels et al. [35] | 76 | 41 | 38 | |

| Hedman et al. [36] | 6 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Ryd et al. [37] | 11 | 5 | 2 | 4 |

| Heatwole et al. [38] | 10 | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mendoza-Holgado, C.; García-González, I.; López-Espuela, F. Digitalization of Activities of Daily Living and Its Influence on Social Participation for Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12050504

Mendoza-Holgado C, García-González I, López-Espuela F. Digitalization of Activities of Daily Living and Its Influence on Social Participation for Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2024; 12(5):504. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12050504

Chicago/Turabian StyleMendoza-Holgado, Cristina, Inmaculada García-González, and Fidel López-Espuela. 2024. "Digitalization of Activities of Daily Living and Its Influence on Social Participation for Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Scoping Review" Healthcare 12, no. 5: 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12050504

APA StyleMendoza-Holgado, C., García-González, I., & López-Espuela, F. (2024). Digitalization of Activities of Daily Living and Its Influence on Social Participation for Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 12(5), 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12050504