Use of a Virtual Multi-Disciplinary Clinic for the Treatment of Post-COVID-19 Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. The Dedicated Post-COVID-19 Clinic

2.2. Satisfaction Survey

3. Analysis

4. Results

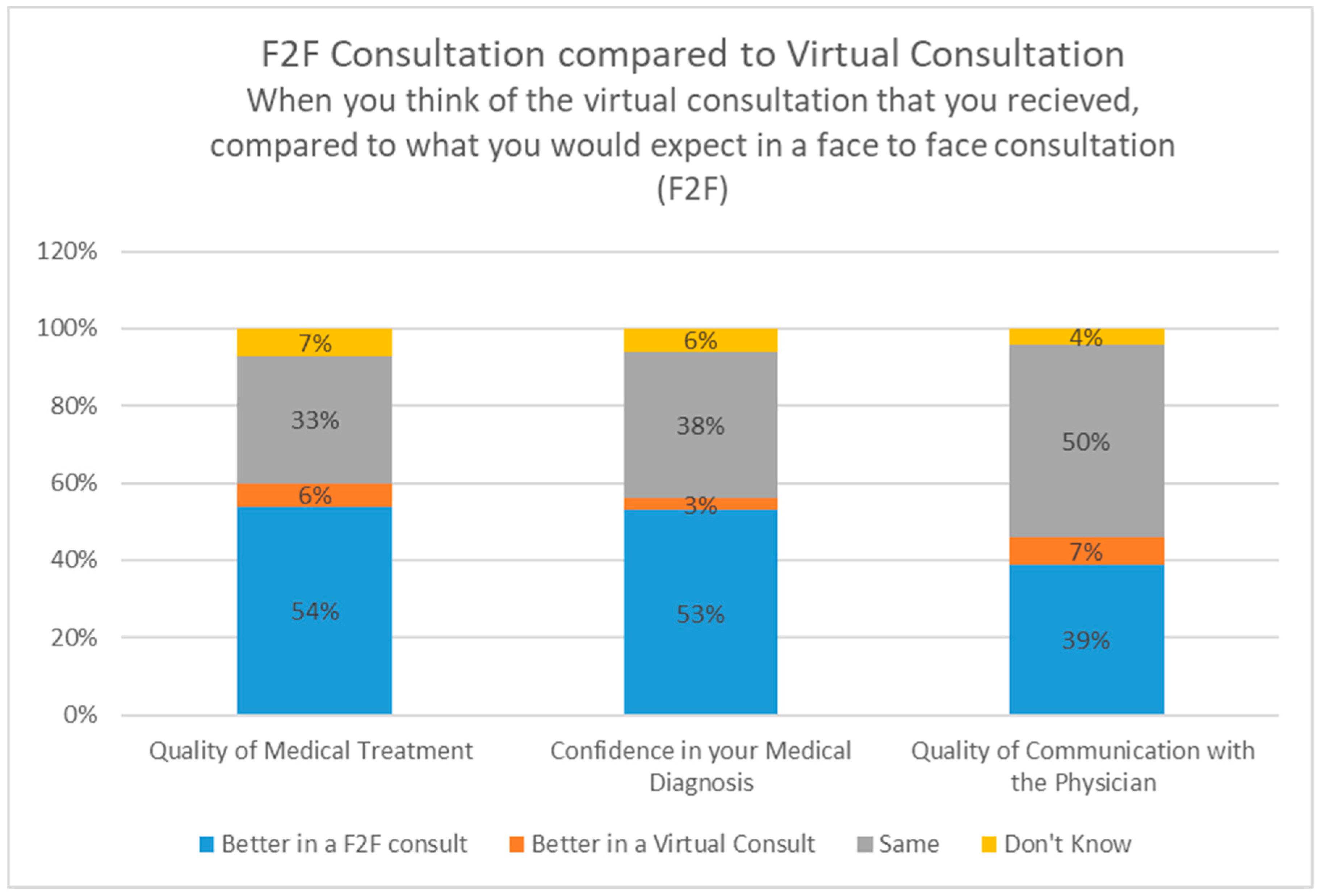

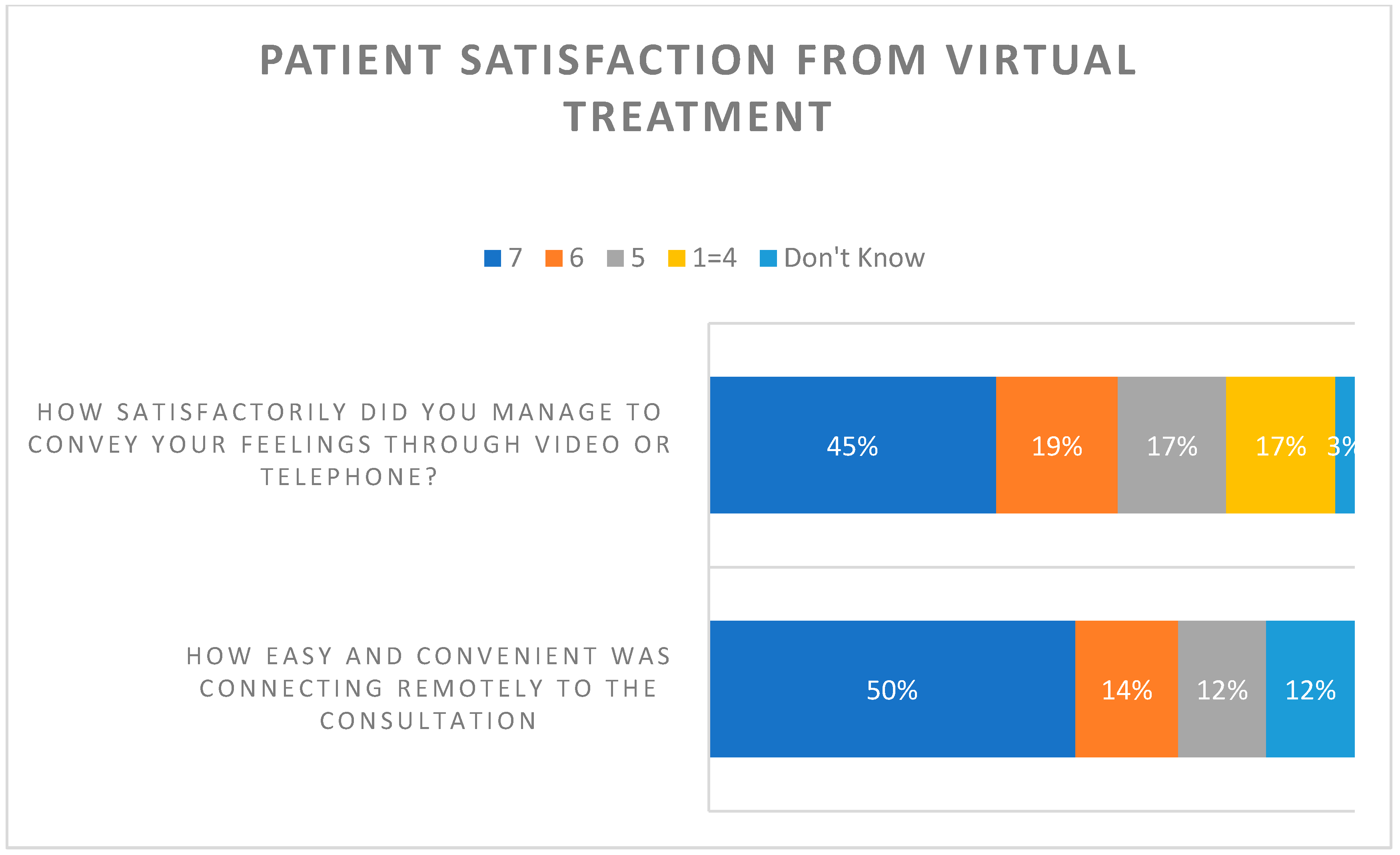

Patient Satisfaction Survey

5. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VPCC | Virtual Post-COVID Clinic |

| F2F | face to face |

References

- Davis, H.E.; McCorkell, L.; Vogel, J.M.; Topol, E.J. Long COVID: Major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 133–146, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Gu, X.; Kang, L.; Guo, L.; Liu, M.; Zhou, X.; et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: A cohort study. Lancet 2021, 397, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coronavirus Resource Center. COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. 2022. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (accessed on 26 June 2022).

- David, S.S.B.; Cohen, D.; Karplus, R.; Irony, A.; Ofer-Bialer, G.; Potasman, I.; Greenfeld, O.; Azuri, J.; Ash, N. COVID-19 community care in Israel—A nationwide cohort study from a large health maintenance organization. J. Public Health 2021, 43, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudre, C.; Murray, B.; Varsavsky, T.; Graham, M.; Penfold, R.; Bowyer, R. Attributes and predictors of Long-COVID: Analysis of COVID cases and their symptoms collected by the Covid Symptoms Study App. BMJ 2020. [CrossRef]

- Soriano, J.B.; Murthy, S.; Marshall, J.C.; Relan, P.; Diaz, J.V.; WHO Clinical Case Definition Working Group on Post-COVID-19 Condition. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, e102–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeting the challenge of long, COVID. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1803. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Leon, S.; Wegman-Ostrosky, T.; Perelman, C.; Sepulveda, R.; Rebolledo, P.A.; Cuapio, A.; Villapol, S. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parotto, M.; Gyöngyösi, M.; Howe, K.; Myatra, S.N.; Ranzani, O.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Herridge, M.S. Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19: Understanding and addressing the burden of multisystem manifestations. Lancet Respir. Med. 2023, 11, 739–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Haupert, S.R.; Zimmermann, L.; Shi, X.; Fritsche, L.G.; Mukherjee, B. Global Prevalence of Post-Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Condition or Long COVID: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 226, 1593–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Décary, S.; De Groote, W.; Arienti, C.; Kiekens, C.; Boldrini, P.; Lazzarini, S.G.; Dugas, M.; Stefan, T.; Langlois, L.; Daigle, F.; et al. Scoping review of rehabilitation care models for post COVID-19 condition. Bull. World Health Organ. 2022, 100, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verduzco-Gutierrez, M.; Estores, I.M.; Graf, M.J.P.; Barshikar, S.; Cabrera, J.A.; Chang, L.E.; Eapen, B.C.; Bell, K.R. Models of Care for Postacute COVID-19 Clinics: Experiences and a Practical Framework for Outpatient Physiatry Settings. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 100, 1133–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallmach, A.; Katzer, K.; Besteher, B.; Finke, K.; Giszas, B.; Gremme, Y.; Abou Hamdan, R.; Lehmann-Pohl, K.; Legen, M.; Lewejohann, J.C.; et al. Mobile primary healthcare for post-COVID patients in rural areas: A proof-of-concept study. Infection 2023, 51, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, A.; Lovas, M.; Truong, T.; Melwani, S.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.A.; Badzynski, A.; Carpenter, M.B.; Virtanen, C.; Morley, L.; et al. Implementation and Outcomes of Virtual Care Across a Tertiary Cancer Center during COVID-19. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, S.; Coyle, L.; Bradley, S.; Wilton, W.; Cordner, J.; Dempster, R.; Lindsay, J.R. Virtual fracture liaison clinics in the COVID era: An initiative to maintain fracture prevention services during the pandemic associated with positive patient experience. Osteoporos. Int. 2021, 32, 1221–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, K.; Chia, M. Patient and clinician satisfaction with video consultations in dentistry—Part one: Patient satisfaction. Br. Dent. J. 2021, 231, 675–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharareh, B.; Schwarzkopf, R. Effectiveness of telemedical applications in postoperative follow-up after total joint arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2014, 29, 918–922.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, E.K.; Herbert, J.D.; Forman, E.M.; Goetter, E.M.; Juarascio, A.S.; Rabin, S.; Goodwin, C.; Bouchard, S. Acceptance based behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder through videoconferencing. J. Anxiety Disord. 2013, 27, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi Reuveni, M.; Kertes, J.; Shapiro Ben David, S.; Shahar, A.; Shamir-Stein, N.; Rosen, K.; Liran, O.; Bar-Yishay, M.; Adler, L. Risk Stratification Model for Severe COVID-19 Disease: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/index.html (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Luo, J.; Tong, L.; Crotty, B.H.; Somai, M.; Taylor, B.; Osinski, K.; George, B. Telemedicine Adoption during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Gaps and Inequalities. Appl. Clin. Inform. 2021, 12, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rayes, S.; Alumran, A.; Aljanoubi, H.; Alkaltham, A.; Alghamdi, M.; Aljabri, D. Awareness and Use of Virtual Clinics following the COVID-19 Pandemic in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heightman, M.; Prashar, J.; Hillman, T.E.; Marks, M.; Livingston, R.; Ridsdale, H.A.; Bell, R.; Zandi, M.; McNamara, P.; Chauhan, A.; et al. Post-COVID-19 assessment in a specialist clinical service: A 12-month, single-centre, prospective study in 1325 individuals. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2021, 8, e001041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.; Nirantharakumar, K.; Hughes, S.; Myles, P.; Williams, T.; Gokhale, K.M.; Taverner, T.; Chandan, J.S.; Brown, K.; Simms-Williams, N.; et al. Symptoms and risk factors for long COVID in non-hospitalized adults. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1706–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrat, I.; Tam, S.; Boulis, M.; Williams, A.M. Socioeconomic Disparities in Patient Use of Telehealth During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Surge. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2021, 147, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latzer, Y.; Herman, E.; Ashkenazi, R.; Atias, O.; Laufer, S.; Biran Ovadia, A.; Oppenheim, T.; Shimoni, M.; Uziel, M.; Stein, D. Virtual Online Home-Based Treatment During the COVID-19 Pandemic for Ultra-Orthodox Young Women with Eating Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 654589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, N.; Laron, M. Use and barriers to the use of telehealth services in the Arab population in Israel: A cross sectional survey. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2023, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimercati, L.; De Maria, L.; Quarato, M.; Caputi, A.; Gesualdo, L.; Migliore, G.; Cavone, D.; Sponselli, S.; Pipoli, A.; Inchingolo, F.; et al. Association between Long COVID and Overweight/Obesity. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-González, A.; Araújo-Ameijeiras, A.; Fernández-Villar, A.; Crespo, M.; Poveda, E.; Cohort COVID-19 of the Galicia Sur Health Research Institute. Long COVID in hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients in a large cohort in Northwest Spain, a prospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3369, Erratum in: Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawrysz, L.; Gierszewska, G.; Bitkowska, A. The Research on Patient Satisfaction with Remote Healthcare Prior to and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2021, 18, 5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predmore, Z.S.; Roth, E.; Breslau, J.; Fischer, S.H.; Uscher-Pines, L. Assessment of Patient Preferences for Telehealth in Post–COVID-19 Pandemic Health Care. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021, 4, e2136405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, M.; Sharma, R. A Review of Patient Satisfaction and Experience with Telemedicine: A Virtual Solution During and Beyond COVID-19 Pandemic. Telemed. J. e-Health 2021, 27, 1325–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Subramain, M.; Barlow, P.B.; Garvin, L.; Hoth, K.F.; Dukes, K.; Hoffman, R.M.; Comellas, A.P. Patient Experiences with a Tertiary Care Post-COVID-19 Clinic. J. Patient Exp. 2023, 10, 23743735231151539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Category | No VPCC Presentation N = 837,968 | VPCC Presentation N = 1614 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic: | ||||

| Sex | % females | 55.2 | 68.0 | <0.001 |

| Age group * | <25 | 20.2 | 11.0 | <0.001 |

| 25–34 | 19.6 | 18.0 | ||

| 35–44 | 18.3 | 22.3 | ||

| 45–54 | 19.5 | 27.6 | ||

| 55–64 | 11.7 | 15.1 | ||

| 65+ | 10.6 | 6.1 | ||

| Population group | General | 86.0 | 90.0 | <0.001 |

| Jewish Orthodox | 9.0 | 7.4 | ||

| Arab | 5.0 | 2.5 | ||

| Socioeconomic status | Low | 18.6 | 15.4 | <0.001 |

| Middle | 44.9 | 54.0 | ||

| High | 36.5 | 30.5 | ||

| Region | North | 17.1 | 18.2 | <0.001 |

| Sharon | 21.6 | 20.4 | ||

| Center | 21.5 | 16.4 | ||

| Jerusalem and Plains | 24.9 | 27.2 | ||

| South | 14.9 | 17.8 | ||

| Health Status | ||||

| Heart disease * | % in registry | 6.3 | 6.1 | 0.814 |

| Diabetes * | % in registry | 6.5 | 6.9 | 0.552 |

| Hypertension * | % in registry | 14.3 | 15.9 | 0.071 |

| Cancer * | % in registry | 5.4 | 4.1 | 0.020 |

| CKD * | % in registry | 7.2 | 7.9 | 0.236 |

| COPD * | % in registry | 1.1 | 1.7 | 0.035 |

| Number of chronic illnesses ** | None | 76.6 | 74.3 | 0.046 |

| One | 13.1 | 15.1 | ||

| Two or more | 10.3 | 10.7 | ||

| Obesity * | % in registry | 8.0 | 2.8 | <0.001 |

| COVID-19 related: | ||||

| Number of episodes * | % with 2+ | 6.6 | 24.2 | <0.001 |

| Hospitalized during episode | % hospitalized | 1.1 | 8.1 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rahamim-Cohen, D.; Kertes, J.; Feldblum, I.; Shamir-Stein, N.; Shapiro Ben David, S. Use of a Virtual Multi-Disciplinary Clinic for the Treatment of Post-COVID-19 Patients. Healthcare 2024, 12, 376. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12030376

Rahamim-Cohen D, Kertes J, Feldblum I, Shamir-Stein N, Shapiro Ben David S. Use of a Virtual Multi-Disciplinary Clinic for the Treatment of Post-COVID-19 Patients. Healthcare. 2024; 12(3):376. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12030376

Chicago/Turabian StyleRahamim-Cohen, Daniella, Jennifer Kertes, Ilana Feldblum, Naama Shamir-Stein, and Shirley Shapiro Ben David. 2024. "Use of a Virtual Multi-Disciplinary Clinic for the Treatment of Post-COVID-19 Patients" Healthcare 12, no. 3: 376. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12030376

APA StyleRahamim-Cohen, D., Kertes, J., Feldblum, I., Shamir-Stein, N., & Shapiro Ben David, S. (2024). Use of a Virtual Multi-Disciplinary Clinic for the Treatment of Post-COVID-19 Patients. Healthcare, 12(3), 376. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12030376