Multicentre Pilot Study to Evaluate the Efficacy of Targeted Exercise in Combination with Cytisinicline on Smoking Cessation at 12 Months: MEDSEC-CTA

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

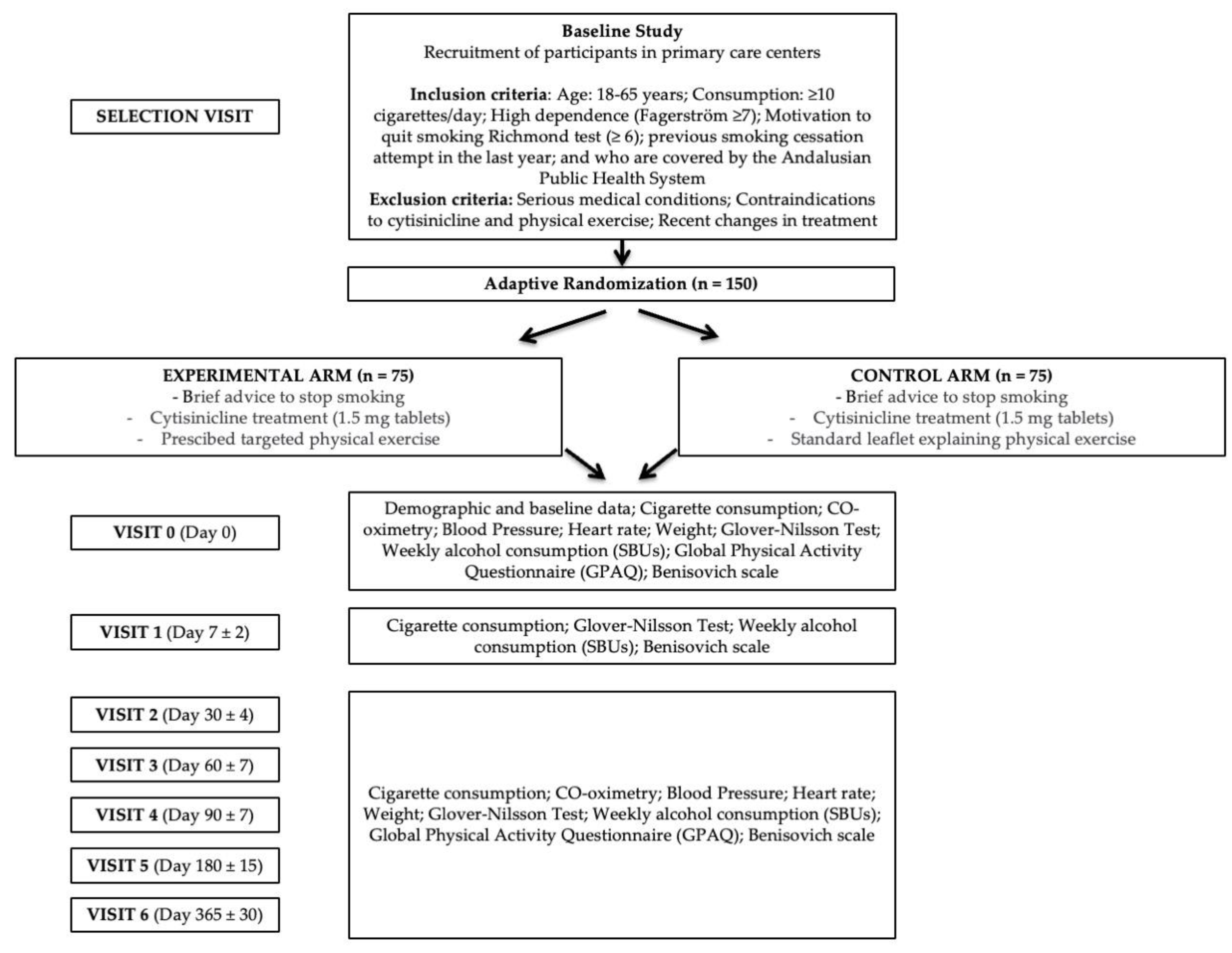

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Sample Size

2.4. Sample Selection or Eligibility Criteria

2.4.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.4.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Recruitment of Participating Smokers

2.6. Branch Allocation and Randomisation

2.7. Source of Data

2.8. Data Management

2.9. Study Variables

2.10. Material Used for Smoking Determination and Other Instruments

2.11. Intervention

- A.

- Smokers who are going to be prescribed targeted physical exercise and brief advice to stop smoking while receiving cytisinicline treatment (1.5 mg tablets) according to the care process: EXPERIMENTAL ARM.

- B.

- Smokers who will receive a standard leaflet explaining physical exercise to the general population and brief advice on smoking cessation when starting cytisinicline treatment, according to the care process: CONTROL ARM.

2.11.1. Prescription of Targeted Physical Exercise

2.11.2. Brief Advice

2.11.3. Pharmacological Treatment with Cytisinicline

2.12. Participant Chronology and Schedule of Visits

- -

- Selection visit (Day 0): FACE-TO-FACE. The potential participant is proposed to participate in the study. A check is made to ensure that the patient has no medical or other history that might contraindicate the prescription of physical exercise. The patient receives the information and signs the informed consent form if he/she wishes to be included in the study.

- -

- Visit 0 (Day 0): FACE-TO-FACE. Baseline data are collected on the previously mentioned variables. The necessary criteria for prescription are completed. The drug is prescribed to be approved within 24h, and a treatment start date is set.

- -

- Visit 1 (Day 7 ± 2): TELEPHONE. Data are collected, and the participant is asked if there are any problems with the motivation to continue.

- -

- Visit 2 (Day 30 ± 4): FACE-TO-FACE. Data are collected, and questions are asked if there have been any problems with the physical exercise, motivating for its continuation.

- -

- Visit 3 (Day 60 ± 7): FACE-TO-FACE. Data are collected, and questions are asked if there have been any problems with the physical exercise, motivating for its continuation.

- -

- Visit 4 (Day 90 ± 7): FACE-TO-FACE. Data are collected, and a question is asked as to whether there have been any problems with the physical exercise, motivating the patient to continue.

- -

- Visit 5 (Day 180 ± 15): FACE-TO-FACE. Data are collected, and a question is asked as to whether there have been any problems with the physical exercise, motivating the patient to continue.

- -

- Visit 6 (Day 365 ± 30): FACE-TO-FACE. Data are collected.

2.13. Statistical Analysis Plan

2.14. Bias Control

2.15. Security Event Reporting

2.16. Ethical and Regulatory Framework

2.17. Ethics Committee

2.18. Amendments to the Protocol

2.19. Informed Consent

2.20. Confidentiality and Data Access Policy

2.21. Declaration of Conflict of Interest

2.22. Performance Advertising Policy

2.23. Gender Perspective

2.24. Registration in Clinical Trials

3. Expected Results

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Project

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Department of Tourism, Culture and Sport. Regional Government of Andalusia. Andalusian Physical Exercise Prescription Plan (PAPEF). Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/sites/default/files/2023-11/Plan%20Andaluz%20de%20Prescripción%20de%20Ejercicio%20F%C3%ADsico%202023-2030.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- American College of Sports Medicine. Quantity and Quality of Exercise for Developing and Maintaining Cardiorespiratory, Musculoskeletal, and Neuromotor Fitness in Apparently Healthy Adults: Guidance for Prescribing Exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1334–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, X.; Tian, X.; Zhang, H.; Huang, R.; Li, N.; Chen, P.; Wang, R. Exercise as a prescription for patients with various diseases. J. Sport Health Sci. 2019, 8, 422–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health. Spanish Government. European Health Survey. 2020. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/EncuestaEuropea/EESE2020_inf_evol_princip_result2.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality. Deaths Attributable to Tobacco Consumption in Spain. 2000–2014; Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality: Madrid, Spain, 2016; Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/estadisticas/estMinisterio/mortalidad/docs/MuertesTabacoEspana2014.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Zhou, Y.; Feng, W.; Guo, Y.; Wu, J. Effect of exercise intervention on smoking cessation: A meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1221898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunicki, Z.J.; Hallgren, M.; Uebelacker, L.A.; Brown, R.A.; Price, L.H.; Abrantes, A.M. Examining the effect of exercise on the relationship between affect and cravings among smokers engaged in cessation treatment. Addict. Behav. 2022, 125, 107156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schöttl, S.E.; Niedermeier, M.; Kopp-Wilfling, P.; Frühauf, A.; Bichler, C.S.; Edlinger, M.; Holzner, B.; Kopp, M. Add-on exercise interventions for smoking cessation in people with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 14, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.D.; Taylor, T.; Stanton, C.; Makambi, K.; Hicks, J.; Adams-Campbell, L.L. A Feasibility Study of Smoking Cessation Utilizing an Exercise Intervention among Black Women: ‘Quit and Fit’. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2021, 113, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.O.; Norcross, J.C. Stages of change. Psychother Theory Res. Pract. Train. 2001, 38, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordoba Health District. Distrito Sanitario Córdoba y Guadalquivir. Available online: https://www.sspa.juntadeandalucia.es/servicioandaluzdesalud/el-sas/servicios-y-centros/informacion-por-centros/23610 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- XXV Semana sin Humo. Resultados de la encuesta 2023. 2021. Available online: https://semanasinhumo.es/resultados (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Ussher, M.; West, R.; McEwen, A.; Taylor, A.; Steptoe, A. Efficacy of exercise counselling as an aid for smoking cessation: A randomized controlled trial. Addiction 2003, 98, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussher, M.; West, R.; McEwen, A.; Taylor, A.; Steptoe, A. Randomized controlled trial of physical activity counseling as an aid to smoking cessation: 12 month follow-up. Addict. Behav. 2007, 32, 3060–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bize, R.; Willi, C.; Chiolero, A.; Stoianov, R.; Payot, S.; Locatelli, I.; Cornuz, J. Participation in a population-based physical activity programme as an aid for smoking cessation: A randomised trial. Tob. Control 2010, 19, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockton, M.B.; Ward, K.D.; McClanahan, B.S.; Vander Weg, M.W.; Coday, M.; Wilson, N.; Relyea, G.; Read, M.C.; Conelly, S.; Johnson, K.C. The Efficacy of Individualized, Community-Based Physical Activity to Aid Smoking Cessation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Smok. Cessat. 2023, 2023, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TODACITAN 1.5 mg Tablets EFG. Spanish Agency of Medicines and Health Products. 2022. Available online: https://cima.aemps.es/cima/dochtml/ft/83407/FT_83407.html (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- BOE-A-2024-6701 Resolution of 22 March 2024, of the Directorate General of Public Health and Equity in Health, Which Validates the Guide for the Indication, Use and Authorisation of Dispensing of Medicines Subject to Medical Prescription by Nurses: Smoking Cessation. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2024-6701 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Fagerström, K.O. Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addict. Behav. 1978, 3, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glover, E.D.; Nilsson, F.; Westin, Å.; Glover, P.N.; Laflin, M.T.; Persson, B. Glover-Nilsson Smoking Behavioral Questionnaire. 2014. Available online: https://doi.apa.org/doi/10.1037/t32570-000 (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Richmond, R.L.; Kehoe, L.A.; Webster, I.W. Multivariate models for predicting abstention following intervention to stop smoking by general practitioners. Addiction 1993, 88, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ). World Health Organization. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/publications/m/item/global-physical-activity-questionnaire (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Benisovich, S.V.; Rossi, J.S.; Norman, G.J.; Nigg, C.R. Development of a multidimensional measure of exercise self-efficacy. Ann. Behav. Med. 1998, 20, S190. [Google Scholar]

- García Rueda, M.; Ruiz Bernal, A.; Fernández Pérez, M.D.; López Vega, D.J.; López Cabello, P.A.; Reina Ceballos, I.; Carranza Miranda, E.; Barchilón Cohen, V.; Rodríguez Gómez, S.; Mora Luque, M.J.; et al. Comprehensive Smoking Plan for Andalusia (PITA). [Seville]: Consejería de Salud y Consumo; 2022. p. 52. Consejería de Salud y Consumo. Andalusian Regional Government. [Electronic Resource]. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/organismos/saludyconsumo/areas/planificacion/planes-integrales/paginas/pita.html (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Junta de Andalucía. Guide for Professionals. Recommendations for Physical Activity and Prescription of Physical Exercise for Health. 2023. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/sites/default/files/2023-11/Guia%20Profesionales%20Prescripcion%20Ejercicio%20F%C3%ADsico.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Regional Government of Andalusia. ActiVital Application for Mobile Devices. Digitalisation Plan for the Prescription of Physical Exercise in Andalusia. 2023. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/sites/default/files/2023-12/ACTIVITAL.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Gender and Tobacco Control; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/44001/9789241595773_eng.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Eissenberg, T.; Moyer, J.M. The Role of Gender in Tobacco Smoking and Cessation. J. Womens Health 2018, 27, 1220–1230. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan, P.; King, B.A. The Influence of Gender on Smoking Behavior and Nicotine Addiction. Addict. Res. Theory 2015, 23, 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K.D.; Siegel, R.L. Cancer Statistics for Women. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking-50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK179276/ (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Hernandez, I.; Giacalone, D. Gender Differences in Smoking and Its Consequences. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 174, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L.; Sanders, K. Understanding Gender Differences in Tobacco Use: Implications for Public Health Policy. Tob. Control 2020, 29, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, Y.; Miyai, H.; Yi, C.; Oliver, B.G. The effects of exercise with nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation in adults: A systematic review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1053937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba García, R.; Camarelles Guillem, F.; Muñoz Seco, E.; Gómez Puente, J.M.; San José Arango, J.; Rámirez-Manent, J.I.; Martín Cantera, C.; Del Campo Giménez, M.; Revenga Frauca, J.; Egea Ronda, A.; et al. Lifestyle recommendations. Update PAPPS 2022. Atención Primaria 2022, 54, 102442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, R.; Zatonski, W.; Cedzynska, M.; Lewandowska, D.; Pazik, J.; Aveyard, P.; Stapleton, J. Placebo-Controlled Trial of Cytisine for Smoking Cessation. N. Eng. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajek, P.; Mc Robbie, H.; Myers, K. Efficacy of cytisine in helping smokers quit: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2013, 68, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, N.; Howe, C.; Glover, M.; McRobbie, H.; Barnes, J.; Nosa, V.; Parag, V.; Bassett, B.; Bullen, C. Cytisine versus Nicotine for Smoking Cessation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 2353–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, R.J.; McRobbie, H.; Tutka, P.; Weaver, N.A.; Petrie, D.; Mendelsohn, C.P.; Shakeshaft, A.; Talukder, S.; Macdonald, C.; Thomas, D.; et al. Effect of Cytisine vs Varenicline on Smoking Cessation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 326, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, N.; Smith, B.; Barnes, J.; Verbiest, M.; Parag, V.; Pokhrel, S.; Wharakura, M.; Lees, T.; Gutierrez, H.C.; Jones, B.; et al. Cytisine versus varenicline for smoking cessation in New Zealand indigenous Māori: A randomized controlled trial. Addiction 2021, 116, 2847–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nides, M.; Rigotti, N.A.; Benowitz, N.; Clarke, A.; Jacobs, C. A Multicenter, Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Phase 2b Trial of Cytisinicline in Adult Smokers (The ORCA-1 Trial). Nicotine Tob. Res. 2021, 23, 1656–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalbí, J.; Fernández, E. Once Upon a Time... Smoking Began Its Decline Among Women in Spain. Tob. Prev. Cessat. 2016, 2, 16. Available online: http://www.journalssystem.com/tpc/Once-upon-a-time-smoking-began-its-decline-among-women-in-Spain,62020,0,2.html (accessed on 20 February 2024). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jiménez-Ruiz, C.A.; Riesco Miranda, J.A.; Martínez Picó, A.; Gutiérrez, R.d.S.; Miñana, J.S.-C.; Muñoz, J.L.D.M.; Torres, J.S. The DESTINA Study: An Observational Cross-sectional Study to Evaluate Patient Satisfaction and Tolerability of Cytisine for Smoking Cessation in Spain. Arch. De Bronconeumol. 2022, 59, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodczyk, A.M.; Gruba, G.; Sikora, Z.; Kasiak, P.S.; Gębarowska, J.; Adamczyk, N.; Mamcarz, A.; Śliż, D. PaLS Study: How Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Influenced Physical Activity and Nutrition? Observations a Year after the Outbreak of the Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Visit | Level Exercise | Type of Exercise | Proposed Exercise (Sets and Repetitions) | Frequency (Days/Week) | Intensity (~%HR max/~% 1RM) | Duration per Type (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 0 (Day 0) | Low-Level 1.1 | Cardiorespiratory Endurance | Slow-paced walking or stationary bike | 3–4 | Low (~55–60% max HR) | 20 |

| Low-Level 1.2 | Muscle Strength and Endurance | Bodyweight squats (3 × 10), knee push-ups (3 × 8), lunges (3 × 8), heel raises (3 × 10), plank (3 × 10 s) | 2–3 | Bodyweight exercise or Low (~30–50% 1RM) | 20 | |

| Low-Levell 1.3 | Flexibility or Range of Motion | Basic stretches (15 × 30 s, 4 repetitions per muscle group) | 2–3 | Low | 5 | |

| Low-Level 1.4 | Neuromotor Capabilities | Straight-line walking | 2–3 | Low | ||

| Visit 2 (Day 30 ± 4) | Low-Level 2.1 | Cardiorespiratory Endurance | Brisk walking or moderate stationary bike | 3–4 | Moderate (~65–75% max HR) | 25 |

| Low-Level 2.2 | Muscle Strength and Endurance | Bodyweight squats (3 × 12), inclined push-ups (3 × 8), lunges (3 × 10), heel raises (3 × 12), plank (3 × 15 s) | 3 | Bodyweight exercise or low (~30–50% 1RM) | 20 | |

| Low-Level 2.3 | Flexibility or Range of Motion | Basic stretches for legs and trunk | 2–3 | Low | 5 | |

| Low-Level 2.4 | Neuromotor Capabilities | Static balance exercise (standing on one leg) | 2–3 | Low | ||

| Visit 3 (Day 60 ± 7) | Low-Level 3.1 | Cardiorespiratory Endurance | Brisk walking or steady pace cycling | 3–4 | Moderate (~65–75% max HR) | 30 |

| Low-Level 3.2 | Muscle Strength and Endurance | Bodyweight squats (3 × 15), wall push-ups (3 × 10), lunges (3 × 12), heel raises (3 × 15), plank (3 × 20 sec) | 2–3 | Bodyweight exercise or moderate (~50–70% 1RM) | 25 | |

| Low-Level 3.3 | Flexibility or Range of Motion | Basic stretches for shoulders and hips | 2–3 | Low | 5 | |

| Low-Level 3.4 | Neuromotor Capabilities | Slow lateral movements | 2–3 | Low | ||

| Visit 4 (Day 90 ± 7) | Low-Level 4.1 | Cardiorespiratory Endurance | Brisk walking or light stationary cycling | 3–4 | Moderate (~65–75% max HR) | 30 |

| Low-Level 4.2 | Muscle Strength and Endurance | Knee push-ups (3 × 12), bodyweight squats (3 × 15), lunges (3 × 15), heel raises (3 × 15), plank (3 × 25 s), bicep curls (3 × 12) | 2–3 | Bodyweight exercise or moderate (~50–70% 1RM) | 30 | |

| Low-Level 4.3 | Flexibility or Range of Motion | Stretches to improve leg mobility | 2–3 | Low | 5 | |

| Low-Level 4.4 | Neuromotor Capabilities | Walking with arm swings | 2–3 | Low | ||

| Visit 5 (Day 180 ± 15) | Low-Level 5.1 | Cardiorespiratory Endurance | Walking at a brisk pace or stationary cycling | 4–5 | Moderate (~65–75% max HR) | 30 |

| Low-Level 5.2 | Muscle Strength and Endurance | Bodyweight squats (3 × 20), knee push-ups (3 × 12), lunges (3 × 20), heel raises (3 × 20), plank (3 × 30 s), bicep curls (3 × 15) | 2–3 | Bodyweight exercise or moderate (~50–70% 1RM) | 35 | |

| Low-Level 5.3 | Flexibility or Range of Motion | Stretches for legs and back (low intensity) | 2–3 | Low | 5 | |

| Low-Level 5.4 | Neuromotor Capabilities | Walking with changes in direction | 2–3 | Low |

| Visit | Level Exercise | Type of Exercise | Proposed Exercise | Frequency (Days/Week) | Intensity (~%HR max/~% 1RM) | Duration Per Type (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 0 (Day 0) | Moderate-Level 1.1 | Cardiorespiratory Endurance | Light jog or stationary bike | 3–4 | Moderate (~65–75% max HR) | 25 |

| Moderate-Level 1.2 | Muscle Strength and Endurance | Squats with light barbell (4 × 12), push-ups (3 × 10), lunges (3 × 10), heel raises (3 × 12), plank (3 × 15 sec), bicep curls (3 × 12) | 2–3 | Bodyweight exercise or moderate (~50–70% 1RM) | 25 | |

| Moderate-Level 1.3 | Flexibility or Range of Motion | Low back and leg stretch | 2–3 | Low | 10 | |

| Moderate-Level 1.4 | Neuromotor Capabilities | Walking on a straight line | 2–3 | Moderate | ||

| Visit 2 (Day 30 ± 4) | Moderate-Level 2.1 | Cardiorespiratory Endurance | Moderate jog or stationary bike at a constant pace | 4–5 | Moderate (~65–75% max HR) | 30 |

| Moderate-Level 2.2 | Muscle Strength and Endurance | Squats with moderate weight (4 × 12), push-ups (3 × 12), lunges (3 × 15), heel raises (3 × 15), plank (3 × 20 s), bicep curls (3 × 15) | 2–3 | Bodyweight exercise or moderate (~50–70% 1RM) | 30 | |

| Moderate-Level 2.3 | Flexibility or Range of Motion | Trunk and hip stretches | 3–4 | Moderate | 10 | |

| Moderate-Level 2.4 | Neuromotor Capabilities | Balance on one leg | 2–3 | Moderate | ||

| Visit 3 (Day 60 ± 7) | Moderate-Level 3.1 | Cardiorespiratory Endurance | Continuous jog or light intervals (walk/jog) | 4–5 | Moderate (~65–75% max HR) | 35 |

| Moderate-Level 3.2 | Muscle Strength and Endurance | Squats with barbell (4 × 12), push-ups (3 × 12), lunges (3 × 15), heel raises (3 × 15), plank (3 × 25 s), bicep curls (3 × 15) | 2–3 | Bodyweight exercise or moderate (~50–70% 1RM) | 35 | |

| Moderate-Level 3.3 | Flexibility or Range of Motion | Advanced trunk stretches | 3–4 | Moderate | 10 | |

| Moderate-Level 3.4 | Neuromotor Capabilities | Stair jumps | 2–3 | Moderate | ||

| Visit 4 (Day 90 ± 7) | Moderate-Level 4.1 | Cardiorespiratory Endurance | Light walk and jog intervals | 5–6 | Moderate (~65–75% max HR) | 40 |

| Moderate-Level 4.2 | Muscle Strength and Endurance | Squats with barbell (4 × 15), full push-ups (4 × 12), lunges (3 × 20), heel raises (3 × 20), plank (3 × 30 s), bicep curls (3 × 20) | 3–4 | Bodyweight exercise or moderate (~50–70% 1RM) | 40 | |

| Moderate-Level 4.3 | Flexibility or Range of Motion | Low back and leg stretch | 3–4 | Low | 10 | |

| Moderate-Level 4.4 | Neuromotor Capabilities | March with arm swings | 2–3 | Moderate | ||

| Visit 5 (Day 180 ± 15) | Moderate-Level 5.1 | Cardiorespiratory Endurance | Light walk and jog intervals | 5–6 | Moderate (~65–75% max HR) | 45 |

| Moderate-Level 5.2 | Muscle Strength and Endurance | Squats with barbell (4 × 12), push-ups (3 × 15), lunges (3 × 20), heel raises (3 × 20), plank (3 × 30 s), bicep curls (3 × 20) | 3–4 | Bodyweight exercise or moderate (~50–70% 1RM) | 45 | |

| Moderate-Level 5.3 | Flexibility or Range of Motion | Deeper leg and low back stretches | 3–4 | Low | 10 | |

| Moderate-Level 5.4 | Neuromotor Capabilities | Fast walking with direction changes | 3–4 | Moderate |

| Visit | Level Exercise | Type of Exercise | Proposed Exercise | Frequency (Days/Week) | Intensity (~%HR max/~% 1RM) | Duration Per Type (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 0 (Day 0) | High-Level 1.1 | Cardiorespiratory Endurance | Moderate jog or intervals | 5–6 | Vigorous (~75–90% max HR) | 35 |

| High-Level 1.2 | Muscle Strength and Endurance | Squats with barbell (4 × 12), push-ups (4 × 12), lunges (4 × 15), heel raises (4 × 15), plank with lift (4 × 15 s), dumbbell rows (4 × 12) | 3–4 | Bodyweight exercise or vigorous (~70–85% 1RM) | 40 | |

| High-Level 1.3 | Flexibility or Range of Motion | Deep stretches | 2–3 | Moderate | 5 | |

| High-Level 1.4 | Neuromotor Capabilities | Advanced dynamic balance exercises | 2–3 | Vigorous | ||

| Visit 2 (Day 30 ± 4) | High-Level 2.1 | Cardiorespiratory Endurance | Jog or stationary bike at a steady pace | 5–6 | Vigorous (~75–90% max HR) | 40 |

| High-Level 2.2 | Muscle Strength and Endurance | Squats (4 × 12), push-ups (4 × 12), lunges (4 × 12), heel raises (4 × 12), plank (4 × 12 s), dumbbell rows (4 × 12) | 3–4 | Bodyweight exercise or vigorous (~70–85% 1RM) | 45 | |

| High-Level 2.3 | Flexibility or Range of Motion | Dynamic stretches | 2–3 | Moderate | 15 | |

| High-Level 2.4 | Neuromotor Capabilities | Complex coordination exercises (ladder, jumps) | 2–3 | Vigorous | ||

| Visit 3 (Day 60 ± 7) | High-Level 3.1 | Cardiorespiratory Endurance | High-intensity intervals (HIIT) | 5–6 | Vigorous (~75–90% max HR) | 45 |

| High-Level 3.2 | Muscle Strength and Endurance | Squats (4 × 12), push-ups (4 × 12), lunges (4 × 12), heel raises (4 × 12), plank with lift (4 × 15 s), dumbbell rows (4 × 12) | 3–4 | Bodyweight exercise or Vigorous (~70–85% 1RM) | 50 | |

| High-Level 3.3 | Flexibility or Range of Motion | Advanced stretches | 2–3 | Moderate | 15 | |

| High-Level 3.4 | Neuromotor Capabilities | Advanced coordination exercises (agility ladder) | 2–3 | Vigorous | ||

| Visit 4 (Day 90 ± 7) | High-Level 4.1 | Cardiorespiratory Endurance | HIIT (vigorous intensity intervals) | 5–6 | Vigorous (~75–90% max HR) | 50 |

| High-Level 4.2 | Muscle Strength and Endurance | Squats (4 × 12), advanced push-ups (4 × 12), lunges (4 × 12), heel raises (4 × 12), plank with lift (4 × 12 s), dumbbell rows (4 × 12) | 3–4 | Bodyweight exercise or vigorous (~70–85% 1RM) | 55 | |

| High-Level 4.3 | Flexibility or Range of Motion | Dynamic stretches | 2–3 | Moderate | 15 | |

| High-Level 4.4 | Neuromotor Capabilities | Advanced balance exercises with unstable platform | 2–3 | Vigorous | ||

| Visit 5 (Day 180 ± 15) | High-Level 5.1 | Cardiorespiratory Endurance | HIIT with combined strength work | 5–6 | Vigorous (~75–90% max HR) | 55 |

| High-Level 5.2 | Muscle Strength and Endurance | Squats (4 × 12), advanced push-ups (4 × 12), lunges (4 × 12), heel raises (4 × 12), plank (4 × 15 s), dumbbell rows (4 × 12) | 3–4 | Bodyweight exercise or vigorous (~70–85% 1RM) | 60 | |

| High-Level 5.3 | Flexibility or Range of Motion | Deep stretches | 2–3 | Moderate | 15 | |

| High-Level 5.4 | Neuromotor Capabilities | Advanced dynamic balance exercises | 2–3 | Vigorous |

| Days of Treatment | Recommended Dosage (1.5 mg) | Maximum Daily Dose |

|---|---|---|

| From the 1st to the 3rd day | 1 tablet every 2 h | 6 tablets |

| From the 4th to the 12th day | 1 tablet every 2.5 h | 5 tablets |

| From the 13th to the 16th day | 1 tablet every 3 h | 4 tablets |

| From the 17th to the 20th day | 1 tablet every 5 h | 3 tablets |

| From the 21st to the 25th day | 1–2 tablets per day | 2 tablets |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruiz-Salcedo, S.; Ranchal-Sanchez, A.; Ruiz-Moruno, J.; Montserrat-Villatoro, J.; Jurado-Castro, J.M.; Romero-Rodriguez, E. Multicentre Pilot Study to Evaluate the Efficacy of Targeted Exercise in Combination with Cytisinicline on Smoking Cessation at 12 Months: MEDSEC-CTA. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2516. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12242516

Ruiz-Salcedo S, Ranchal-Sanchez A, Ruiz-Moruno J, Montserrat-Villatoro J, Jurado-Castro JM, Romero-Rodriguez E. Multicentre Pilot Study to Evaluate the Efficacy of Targeted Exercise in Combination with Cytisinicline on Smoking Cessation at 12 Months: MEDSEC-CTA. Healthcare. 2024; 12(24):2516. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12242516

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuiz-Salcedo, Sofia, Antonio Ranchal-Sanchez, Javier Ruiz-Moruno, Jaime Montserrat-Villatoro, Jose Manuel Jurado-Castro, and Esperanza Romero-Rodriguez. 2024. "Multicentre Pilot Study to Evaluate the Efficacy of Targeted Exercise in Combination with Cytisinicline on Smoking Cessation at 12 Months: MEDSEC-CTA" Healthcare 12, no. 24: 2516. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12242516

APA StyleRuiz-Salcedo, S., Ranchal-Sanchez, A., Ruiz-Moruno, J., Montserrat-Villatoro, J., Jurado-Castro, J. M., & Romero-Rodriguez, E. (2024). Multicentre Pilot Study to Evaluate the Efficacy of Targeted Exercise in Combination with Cytisinicline on Smoking Cessation at 12 Months: MEDSEC-CTA. Healthcare, 12(24), 2516. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12242516