Effect of a Health Education Intervention to Reduce Fear of Falling and Falls in Older People: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial Protocol

Abstract

1. Introduction

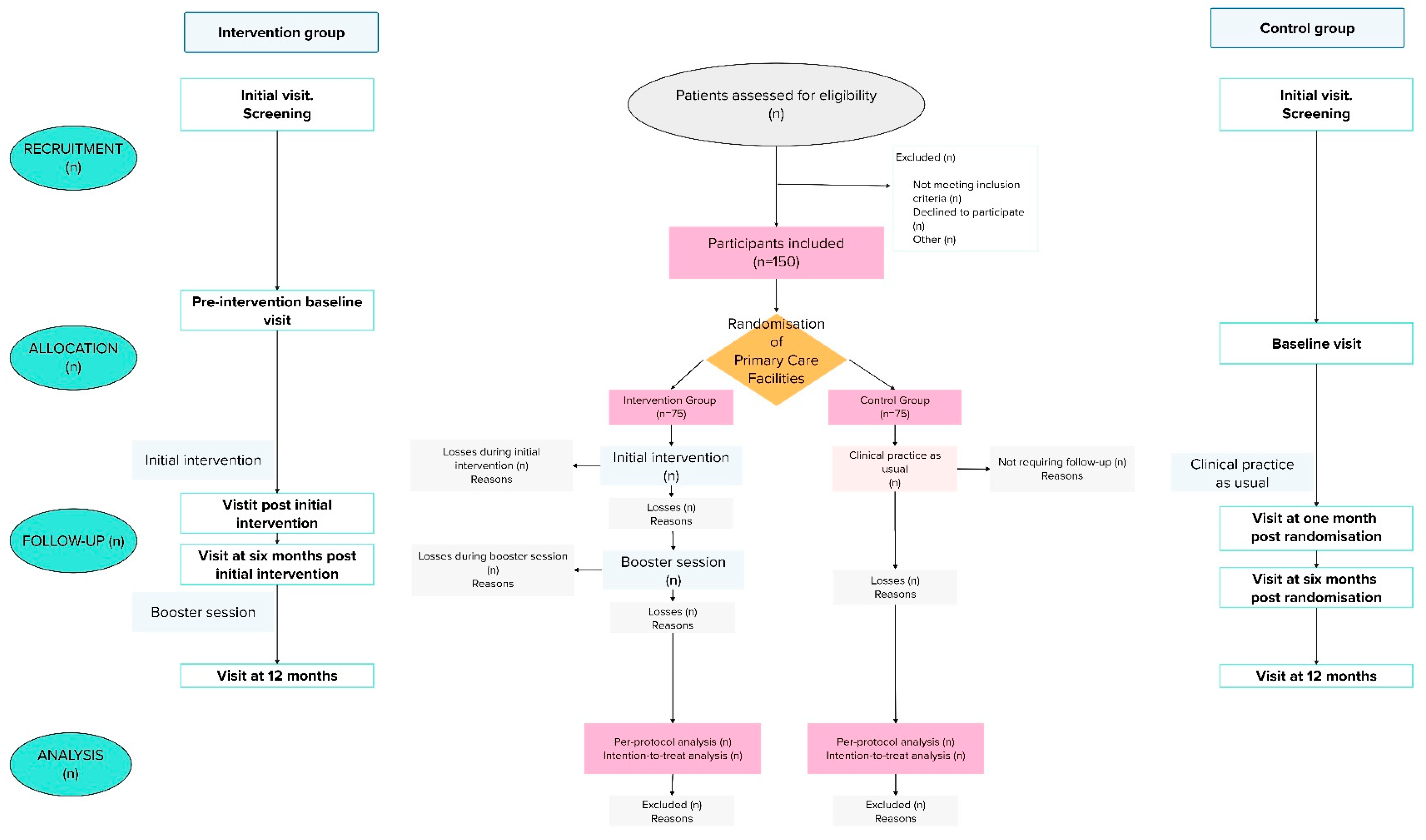

2. Experimental Design

2.1. Aims

2.1.1. Primary Objective

2.1.2. Secondary Objectives

- To assess the effectiveness of implementing a health education intervention to reduce falls in community-dwelling individuals over 65 years of age.

- To analyze the relationships between patients’ sociodemographic, clinical, and functional variables and each of the following: the FES-I short questionnaire scores and the incidence of falls in both the control and intervention groups.

- To analyze the effect of a health education intervention on functional variables, emotional state, ability to practice self-care, and perceived health.

2.2. Research Hypothesis

2.3. Design

2.4. Setting of This Study

2.5. Recruitment of Facilities and Professionals

2.6. Study Population

2.6.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Individuals over 65 years of age on the start date of this study.

- Individuals who are independent for activities of daily living or with mild functional dependence (Barthel Index score ≥ 60 and Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) ≥ 4).

- Independent for ambulation (can walk 45 m unaided or with a cane).

- Without cognitive impairment (Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) ≥ 24).

- With FOF (short FES-I ≥ 11).

2.6.2. Exclusion Criteria

- People with the following medical diagnoses or health conditions (coded according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD–10):

- -

- Diagnosis of mental, behavioral, or neurodevelopmental disorders: delirium, dementia, amnestic disorders, or other cognitive disorders (F05.0; F05.9; F00; F02.8; F03; F04; R41.3; F06.9). Mental disorders caused by a general medical condition, not elsewhere classified (F06.1; F07.0; F09). Schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders (F20; F22; F23; F24; F29).

- -

- Diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases: Parkinson’s disease (G20); Alzheimer’s disease (G30); multiple sclerosis (G35); myasthenia gravis, or other myoneuronal disorders (G70).

- -

- Diagnosis of blindness or low vision (H54).

- -

- Diagnosis of conductive or sensorineural hearing loss, bilateral or uncorrected with a hearing aid (H90.0; H90.2; H90.5; H90.6; H90.8) or other types of hearing loss (H83.3; H91), as long as it impairs participants’ understanding.

- -

- Diagnosis of acute ischemic heart diseases and cerebrovascular diseases in the previous year (I20–I24; I60–I63; I67; I68).

- -

- Other diseases of the circulatory system that contraindicate the multicomponent physical exercise program [31]: other forms of heart disease (I30–I52) (e.g., uncontrolled atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, dissecting aortic aneurysm, severe aortic stenosis, acute endocarditis/pericarditis, uncontrolled arterial hypertension, acute thromboembolic disease, severe acute heart failure, severe acute respiratory failure, uncontrolled orthostatic hypotension; diabetes mellitus with acute decompensation or uncontrolled hypoglycemia (E10-E14), recent fracture in the last month (T14.2) (for strength training) or any other circumstance that the professional considers prevents this type of patients from performing physical activity in the program.

- Hospitalization during the recruitment period or expected admissions during the study period.

- Institutionalized patients or with frequent changes in address.

2.6.3. Withdrawal Criteria

2.7. Sample Size

2.8. Randomization

2.9. Study Blinding

2.10. Training

2.11. Study Variables

2.11.1. Primary Outcome Variable

2.11.2. Secondary Outcome Variable

2.11.3. Explanatory Variables

- Sociodemographic variables: sex, age, marital status, number of cohabiting individuals, level of education, personal net monthly income, current or previous occupation, availability and type of support at home, perceived ability to receive family support, neighborhood, basic healthcare district, the Medea index (used to measure social inequalities in Spain), time spent in the neighborhood in years, housing characteristics, most frequent type of housing in the neighborhood, accessibility to basic services, perceived safety and walkability of the neighborhood.

- Functional variables: the Downton scale, the Barthel index, the SPPB scale total score, four-meter gait disturbance, balance disturbance, loss of lower limb strength, the Lawton-Brody index, physical activity recommended for this age group by the Spanish Ministry of Health (i.e., 150 min of moderate physical activity or 75 min of vigorous physical activity; balance exercises; muscle strengthening exercises; flexibility exercises). Data on this variable will be collected separately, and patients will be considered as meeting the recommended physical activity level, provided that 75% of the activities are carried out. This will include a variable regarding how many dimensions (from one to four) are met by the patient.

- Clinical variables: falls in the previous year (pre intervention); falls during intervention; fall-associated injuries (pre intervention, during intervention, and post intervention); mild visual problems or use of glasses; mild hypoacusis, either unilateral or corrected with a hearing aid; use of a walking device; pain (using a verbal numerical scale); anxiety (via the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) questionnaire); depression (via the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8); ability to practice self-care (via the Appraisal of Self-Care Agency Scale-Revised (ASA-R)); cognitive level (using the Mini-Mental State Examination); perceived health status; body mass index; urinary incontinence, comorbidities (using the Charlson index); medication; polypharmacy; high blood pressure; nursing diagnosis of risk of falling.

- Usual footwear variables: heel height in centimeters, type of sole, sole material, type of fastening.

- Feasibility and acceptability variables:

- ○

- Feasibility (to be measured among professionals): recruitment rate, randomization, adherence to the health education intervention, follow-ups performed, safety/adverse events, difficulties in implementing the health education intervention. To be assessed at the end of the clinical trial.

- ○

- Acceptability (to be assessed in patients assigned to the intervention group):

- -

- Participants: at the end of the health education intervention, data on its utility, usability, satisfactoriness, recommendability, as well as other open questions will be collected.

- -

- Professionals: data on the utility, usability, and satisfactoriness of the program, as well as their readiness to repeat it and other open questions will be collected.

3. Materials and Equipment

4. Detailed Procedure

4.1. Intervention Group Arm

- NIC 1665. Functional ability enhancement.

- NIC 5612. Teaching: prescribed exercise.

- NIC 6490. Fall prevention.

- NIC 6486. Environmental management: safety.

- NIC 4700. Cognitive restructuring.

- NIC 5820. Anxiety reduction.

- NIC 5230. Coping enhancement.

4.2. Control Group Arm

4.3. Visit Plan

- -

- Initial visit: screening.

- -

- Pre-intervention baseline visit: Collection of data on variables. Approximate duration: 60–80 min. The patients assigned to the control group shall carry it out up to two weeks before the beginning of the initial health education intervention.

- -

- Five initial sessions with the intervention group.

- -

- Visit post initial intervention (visit window: ±4–8 weeks after randomization (for the control group) or ±2 weeks after the initial sessions (for the intervention group)): Collection of data on variables. Approximate duration: 25 min.

- -

- Visit at six months post initial intervention (visit window: ±2–4 weeks, at six months after randomization (for the control group) or after the initial health education intervention (for the intervention group)), always prior to the booster session. Collection of data on variables. The structured education plan proposed in the Portfolio of Services will be reviewed in both groups, as well as in the patients in the intervention group, including a follow-up of the issues identified during the health education intervention. Approximate duration: 45 min.

- -

- Booster session with the intervention group.

- -

- Visit at 12 months (visit window: ±2–4 weeks, at 12 months post randomization in the control group or at 6 months after the booster session in the intervention group). Collection of data on variables. Approximate duration: 20 min.

4.4. Data Analysis

4.5. Validity and Reliability/Rigor

4.6. Clinical Risk Management

- -

- Screening and pre-selection visits will allow the assessment of the baseline physical and mental condition of the participants, which will ensure whether they can safely participate in the multicomponent exercise program. Inclusion criteria include that participants must be independent for activities of daily living or with mild functional dependence, independent for walking, and not present cognitive impairment (details are given in the inclusion and exclusion criteria section).

- -

- The intervention visit will be carried out by nurses specifically trained in the field of primary care to implement the program, who will monitor the performance of the activities and ensure their adaptation to the functional capacities of each individual. Homogeneous training of the professionals involved in this study will ensure the safe implementation of the intervention.

- -

- Follow-up visits will allow close monitoring of each participant to monitor and detect possible conditions that pose a risk to health.

- -

- If during the intervention/follow-up a change in the patient’s clinical condition is detected that is a criterion for withdrawal, to ensure patient safety, the patient will not continue in this study. In addition, the patient will be followed up either in primary care or, if necessary, in specialized care.

5. Expected Results

Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tinetti, M.E.; Richman, D.; Powell, L. Falls efficacy as a measure of fear of falling. J. Gerontol. 1990, 45, P239–P243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Hou, L.; Zhao, H.; Xie, R.; Yi, Y.; Ding, X. Risk factors for falls among community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 2023, 9, 1019094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavedán, A.; Viladrosa, M.; Jürschik, P.; Botigué, T.; Nuín, C.; Masot, O.; Lavedán, R. Fear of falling in community-dwelling older adults: A cause of falls, a consequence, or both? PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Oh, E.; Hong, G.R.S. Comparison of factors associated with fear of falling between older adults with and without a fall history. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Bae, S.M. Association between Fear of Falling (FOF) and all-cause mortality. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 88, 104017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, F.; Monteiro, A.M.; Forte, P.; Morouço, P. Effects of muscle strength, agility, and fear of falling on risk of falling in older adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoene, D.; Heller, C.; Aung, Y.N.; Sieber, C.C.; Kemmler, W.; Freiberger, E. A systematic review on the influence of fear of falling on quality of life in older people: Is there a role for falls? Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 701–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcolea-Ruiz, N.; Alcolea-Ruiz, S.; Esteban-Paredes, F.; Beamud-Lagos, M.; Villar-Espejo, M.T.; Pérez-Rivas, F.J. Prevalence of fear of falling and related factors in community-dwelling older people. Aten. Primaria 2021, 53, 101962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, Y.; Arima, K.; Tsujimoto, R.; Kawashiri, S.-Y.; Nishimura, T.; Mizukami, S.; Okabe, T.; Tanaka, N.; Honda, Y.; Izutsu, K.; et al. Prevalence of fear of falling and associated factors among Japanese community-dwelling older adults. Medicine 2018, 97, e9721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdullgader, A.; Rabbani, U. Prevalence and risk factors of falls among the elderly in Unaizah City, Saudi Arabia. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2021, 21, e86–e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.; Gadkari, R.; Nagarkar, A. Risk factors for fear of falling in older adults in India. J. Public Health 2020, 28, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, M.T.H.; Thonglor, R.; Moncatar, T.J.R.; Han, T.D.T.; Tejativaddhana, P.; Nakamura, K. Fear of falling and associated factors among older adults in Southeast Asia: A systematic review. Public Health 2023, 222, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, A.D.; Mathers, C.D.; Ezzati, M.; Jamison, D.T.; Murray, C.J.L. Measuring the global burden of disease and risk factors, 1990–2001. Glob. Burd. Dis. Risk Factors; 2006. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11817/ (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Ferrer, A.; Formiga, F.; Sanz, H.; de Vries, O.J.; Badia, T.; Pujol, R.; Group, O.S. Multifactorial assessment and targeted intervention to reduce falls among the oldest-old: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergen, G.; Stevens, M.R.; Burns, E.R. Falls and fall injuries among adults aged ≥ 65 years—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2016, 65, 993–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dueñas, E.P.; Ramírez, L.P.; Ponce, E.; Curcio, C.L. Effect on fear of falling and functionality of three intervention programs: A randomized clinical trial. Rev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2019, 54, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruisbrink, M.; Delbaere, K.; Kempen, G.I.J.M.; Crutzen, R.; Ambergen, T.; Cheung, K.-L.; Kendrick, D.; Iliffe, S.; Zijlstra, G.A.R. Intervention characteristics associated with a reduction in fear of falling among community-dwelling older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gerontologist 2021, 61, e269–e282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.W.; Ng, G.Y.F.; Chung, R.C.K.; Ng, S.S.M. Cognitive behavioural therapy for fear of falling and balance among older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whipple, M.; Hamel, A.; Talley, K.M.C. Fear of falling among community-dwelling older adults: A scoping review to identify effective evidence-based interventions. Geriatr. Nurs. 2018, 39, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ángeles, C.M.M.; Laura, A.M.; Consuelo, C.S.M.; Manuel, R.R.; Eva, A.C.; Covadonga, G.P.A. The effect that the Otago Exercise Programme had on fear of falling in community dwellers aged 65–80 and associated factors. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2022, 99, 104579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourado, F.W.; Moreira, A.C.A.; Salles, D.L.; da Silva, M.A.M. Interventions to prevent falls in older adults in Primary Care: A systematic review. Acta Paul. Enferm. 2022, 35, eAPE02256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerards, M.; Marcellis, R.; Senden, R.; Poeze, M.; de Bie, R.; Meijer, K.; Lenssen, A. The effect of perturbation-based balance training on balance control and fear of falling in older adults: A single-blind randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapierre, N.; Um Din, N.; Belmin, J.; Lafuente-Lafuente, C. Exergame-assisted rehabilitation for preventing falls in older adults at risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerontology 2023, 69, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robson, K.; Ahasan, N.; Barnes, C.; Murphy, K.; Pope, R. Increasing Physical Activity in Older Australians to Reduce Falls: A Program Evaluation. Internet J. Allied Health Sci. Pract. 2021, 19, 3. Available online: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/ijahsp/vol19/iss3/3 (accessed on 1 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-Lefevre, R. Aplicación del Proceso Enfermero. Fomentar el Cuidado en Colaboración, 5th ed.; Elsevier: Barcelona, España, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Fernández, S. Efectividad de la Utilización de la Metodología Enfermera en la Incidencia de Caídas en Población Anciana de la Comunidad de Madrid. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas, F.J.P.; Juanena, M.O.; García, J.M.S.; López, M.G.; Ramos, V.S.; Lagos, M.B.; de Pareja Palmero, M.J.G. Aplicación de la metodología enfermera en atención primaria. Rev. Calid Asist. 2006, 21, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rivas, F.J.; Martín-Iglesias, S.; Pacheco del Cerro, J.L.; Minguet Arenas, C.; García López, M.; Beamud Lagos, M. Effectiveness of nursing process use in primary care. Int. J. Nurs. Knowl. 2016, 27, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Valladolid, J.; Salinero-Fort, M.A.; Gómez-Campelo, P.; de Burgos-Lunar, C.; Abánades-Herranz, J.C.; Arnal-Selfa, R.; Andrés, A.L. Effectiveness of standardized nursing care plans in health outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A two-year prospective follow-up study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iniesta Sánchez, J.; Abad Corpa, E.; Royo Morales, T.; Sáez Soto, A.; Rodriguez Mondéjar, J.J.; Carrillo Alcaraz, A. Evaluación del impacto de un plan de cuidados de enfermería de pacientes con EPOC con diagnóstico enfermero “Manejo inefectivo del régimen terapéutico”, en términos de mejora del criterio de resultado de enfermería (NOC) “Conocimiento del régimen terapeut. Enferm. Glob. 2016, 15, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, M. Programa Multicomponente de Ejercicio Físico para la Prevención de la Fragilidad y el Riesgo de Caídas. Guía Práctica Para la Prescripción de un Programa de Entrenamiento Físico Multicomponente Para la Prevención de la Fragilidad y Caídas en Mayores de 70 Años. Spain: Cofounded by the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union. 2017. Available online: https://www.munideporte.com/imagenes/documentacion/ficheros/0134414d.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Araya, A.X.; Valenzuela, E.; Padilla, O.; Iriarte, E.; Caro, C. Preocupación a caer: Validación de un instrumento de medición en personas mayores chilenas que viven en la comunidad. Rev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2017, 52, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, K.; Makizako, H.; Doi, T.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Hotta, R.; Nakakubo, S.; Suzuki, T.; Shimada, H. Impact of fear of falling and fall history on disability incidence among older adults: Prospective cohort study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2018, 33, 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, K.; Bulechek, G.; Dochterman, J.; Wagner, C. Clasificación de Intervenciones de Enfermería (NIC), 7th ed.; Elsevier: Barcelona, España, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, M.K.; Piaggio, G.; Elbourne, D.R.; Altman, D.G. Consort 2010 statement: Extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2012, 345, e5661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puffer, S.; Torgerson, D.J.; Watson, J. Cluster randomized controlled trials. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2005, 11, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comission of the European Communities. Commission Directive 2005/28/EC of 8 April. 2005 Laying Down Principles and Detailed Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice as Regards Investigational Medicinal Products for Human Use, as Well as the Requirements for Authorisation of the Manufacturing or Importation of Such Products. 2005. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2005/28/oj (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Gobierno de España. Real Decreto 1090/2015, de 4 de Diciembre, por el que se Regulan los Ensayos Clínicos con Medicamentos, los Comités de Ética de la Investigación con Medicamentos y el Registro Español de Estudios Clínicos. Boletín Oficial de Estado, 24 de Diciembre de 2015. pp. 121923–121964. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2015/12/04/1090 (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Gobierno de España. Real Decreto 1030/2006, de 15 de Septiembre, por el que se Establece la Cartera de Servicios Comunes del Sistema Nacional de Salud y el Procedimiento para su Actualización. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 16 de Septiembre de 2006. 1-104. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/prestacionesSanitarias/CarteraDeServicios/docs/BOE-A-1030-2006-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Papalia, G.F.; Papalia, R.; Diaz Balzani, L.A.; Torre, G.; Zampogna, B.; Vasta, S.; Fossati, C.; Alifano, A.M.; Denaro, V. The effects of physical exercise on balance and prevention of falls in older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turunen, K.M.; Tirkkonen, A.; Savikangas, T.; Hänninen, T.; Alen, M.; Fielding, R.A.; Kivipelto, M.; Neely, A.S.; Törmäkangas, T.; Sipilä, S. Effects of physical and cognitive training on falls and concern about falling in older adults: Results from a randomized controlled trial. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2022, 77, 1430–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahedian-Nasab, N.; Jaberi, N.; Shirazi, F.; Kavousipor, S. Effect of virtual reality exercises on balance and fall in elderly people with fall risk: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitthiracha, P.; Eungpinichpong, W.; Chatchawan, U. Effect of Progressive Step Marching Exercise on Balance Ability in the Elderly: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís, C.L.B.; Arrioja, S.G.; Manzano, A.O. Índice de Barthel (IB): Un instrumento esencial para la evaluación funcional y la rehabilitación. Plas Restaur. Neurol. 2005, 4, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno-García, M.J.; Roldán-Chicano, M.T.; Rodríguez-Tello, J.; Meroño-Rivera, M.D.; Dávila-Martínez, R.; Berenguer-García, N. Características de la escala Downton en la valoración del riesgo de caídas en pacientes hospitalizados. Enferm. Clín. 2017, 27, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda-Gallardo, M.; Morales-Asencio, J.M.; Canca-Sánchez, J.C.; Morales-Fernández, Á.; Enríquez de Luna-Rodríguez, M.; Moya-Suarez, A.B.; Mora-Banderas, A.M.; Pérez-Jiménez, C.; Barrero-Sojo, S. Consecuencias de los errores en la traducción de cuestionarios: Versión española del índice Downton. Rev. Calid. Asist. 2015, 30, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M.; Brody, E. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969, 3, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Documento de Consenso Sobre Prevención de Fragilidad y Caídas en la Persona Mayor. Estrategia de Promoción de la Salud y Prevención en el SNS. Informes, Estudios e Investigación, 1st ed.; Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad Centro de Publicaciones: Madrid, Spain, 2022; pp. 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez Llopis, L. Validación de la Escala de Desempeño Físico ‘Short Physical Performance Battery’ en Atención Primaria de Salud. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Alicante, San Vicente del Raspeig, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, R.S.; Momtaz, Y.A.; Shahboulaghi, F.M.; Aghamaleki, M.A. Validity and reliability of charlson comorbidity index (CCI) among iranian community-dwelling older adults. Act. Facul Med. Naiss. 2020, 327, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.; Folstein, S.; McHugh, P. Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patient for the clinician. J. Psychiatry Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, A.; Ezquerra, J.; Gómez Burgada, F.; Sala, J.M.; Seva Díaz, A. El miniexamen, cognoscitivo (un «test» sencillo, práctico, para detectar alteraciones intelectuales en pacientes médicos). Actas Luso-Esp. Neurol. Psiquiatr. 1979, 7, 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Lobo, U.; Saz, P.; Marcos, G.; Día, J.; Cámara, C.; Ventura, T.; Asín, F.M.; Pascual, L.F.; Montañés, J.; Aznar, S. Revalidación y estandarización del miniexamen de cognición (primera versión española del Miniexamen del Estado Mental) en población geriátrica general. Clin. Med. 1999, 112, 767–774. [Google Scholar]

- García-Campayo, J.; Zamorano, E.; Ruiz, M.A.; Pardo, A.; Pérez-Páramo, M.; López-Gómez, V.; Freire, O.; Rejas, J. Cultural adaptation into Spanish of the generalized anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale as a screening tool. Health Qual. Life Out. 2011, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder the GAD-7. Arch. Int. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, B.; Eckl, A.; Herzog, W.; Niehoff, D.; Lechner, S.; Maatouk, I.; Schellberg, D.; Brenner, H.; Müller, H.; Löwe, B.; et al. Assessing generalized anxiety disorder in elderly people using the GAD-7 and GAD-2 scales: Results of a validation study. Am. J. Geriat Psychiatry 2014, 22, 1029–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatry Ann. 2002, 32, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Strine, T.W.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Berry, J.T.; Mokdad, A.H. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 114, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhambra-Borrás, T.; Durá-Ferrandis, E.; Garcés-Ferrer, J.; Sánchez-García, J. The Appraisal of Self-Care Agency Scale—Revised (ASA-R): Adaptation and Validation in a Sample of Spanish Older Adults. Span. J. Psychol. 2017, 20, E48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Short FES-I Scale How Concerned Are You About the Possibility of Falling While…? | Not at All Concerned | Somewhat Concerned | Fairly Concerned | Very Concerned |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Getting dressed or undressed | 1 □ | 2 □ | 3 □ | 4 □ |

| 2. Taking a bath or shower | 1 □ | 2 □ | 3 □ | 4 □ |

| 3. Getting in or out of a chair | 1 □ | 2 □ | 3 □ | 4 □ |

| 4. Going up or down stairs | 1 □ | 2 □ | 3 □ | 4 □ |

| 5. Reaching for something above your head or on the ground | 1 □ | 2 □ | 3 □ | 4 □ |

| 6. Walking up or down a slope | 1 □ | 2 □ | 3 □ | 4 □ |

| 7. Going out to a social event (e.g., religious service, family gathering or club meeting) | 1 □ | 2 □ | 3 □ | 4 □ |

| SUBTOTAL: | Add all the 1’s | Add all the 2’s | Add all the 3’s | Add all the 4’s |

| Short FES-I ≥ 11: Fear of falling | ||||

| Variables | Visits | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Visit. Screening | Pre-Intervention Baseline visit 1 | Five Initial Group Sessions | Visit Post Initial Intervention 2 | Visit at Six Months Post Initial Intervention 3 | Booster Session | Visit at 12 Months 4 | |

| Review of eligibility criteria | x | ||||||

| Informed consent | x | x | |||||

| Primary outcome variable: Short FES-I | x | x | x | x | |||

| Secondary outcome variable: Post intervention falls | x | x | x | x | |||

| EXPLANATORY VARIABLES | |||||||

| Sociodemographic variables | x | ||||||

| Functional variables | x | x | |||||

| Usual footwear | x | x | |||||

| Clinical variables | x | ||||||

| Falls during intervention | x | x | |||||

| Ability to practice self-care | x | x | x | x | |||

| Perceived health and anxiety | x | x | x | x | |||

| Acceptability (among patients) | x | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alcolea-Ruiz, N.; López-López, C.; Pérez-Pérez, T.; Alcolea, S.; FEARFALL_CARE Clinical Care Group; Pérez-Rivas, F.J. Effect of a Health Education Intervention to Reduce Fear of Falling and Falls in Older People: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial Protocol. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2510. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12242510

Alcolea-Ruiz N, López-López C, Pérez-Pérez T, Alcolea S, FEARFALL_CARE Clinical Care Group, Pérez-Rivas FJ. Effect of a Health Education Intervention to Reduce Fear of Falling and Falls in Older People: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial Protocol. Healthcare. 2024; 12(24):2510. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12242510

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlcolea-Ruiz, Nuria, Candelas López-López, Teresa Pérez-Pérez, Sonia Alcolea, FEARFALL_CARE Clinical Care Group, and Francisco Javier Pérez-Rivas. 2024. "Effect of a Health Education Intervention to Reduce Fear of Falling and Falls in Older People: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial Protocol" Healthcare 12, no. 24: 2510. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12242510

APA StyleAlcolea-Ruiz, N., López-López, C., Pérez-Pérez, T., Alcolea, S., FEARFALL_CARE Clinical Care Group, & Pérez-Rivas, F. J. (2024). Effect of a Health Education Intervention to Reduce Fear of Falling and Falls in Older People: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial Protocol. Healthcare, 12(24), 2510. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12242510