Perceptions and Experiences of Primary Care Providers on Their Role in Tobacco Treatment Delivery Based on Their Smoking Status: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Aim

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting and Participants

2.3. Theoretical Framework

2.4. Procedures

- a.

- Data analysis

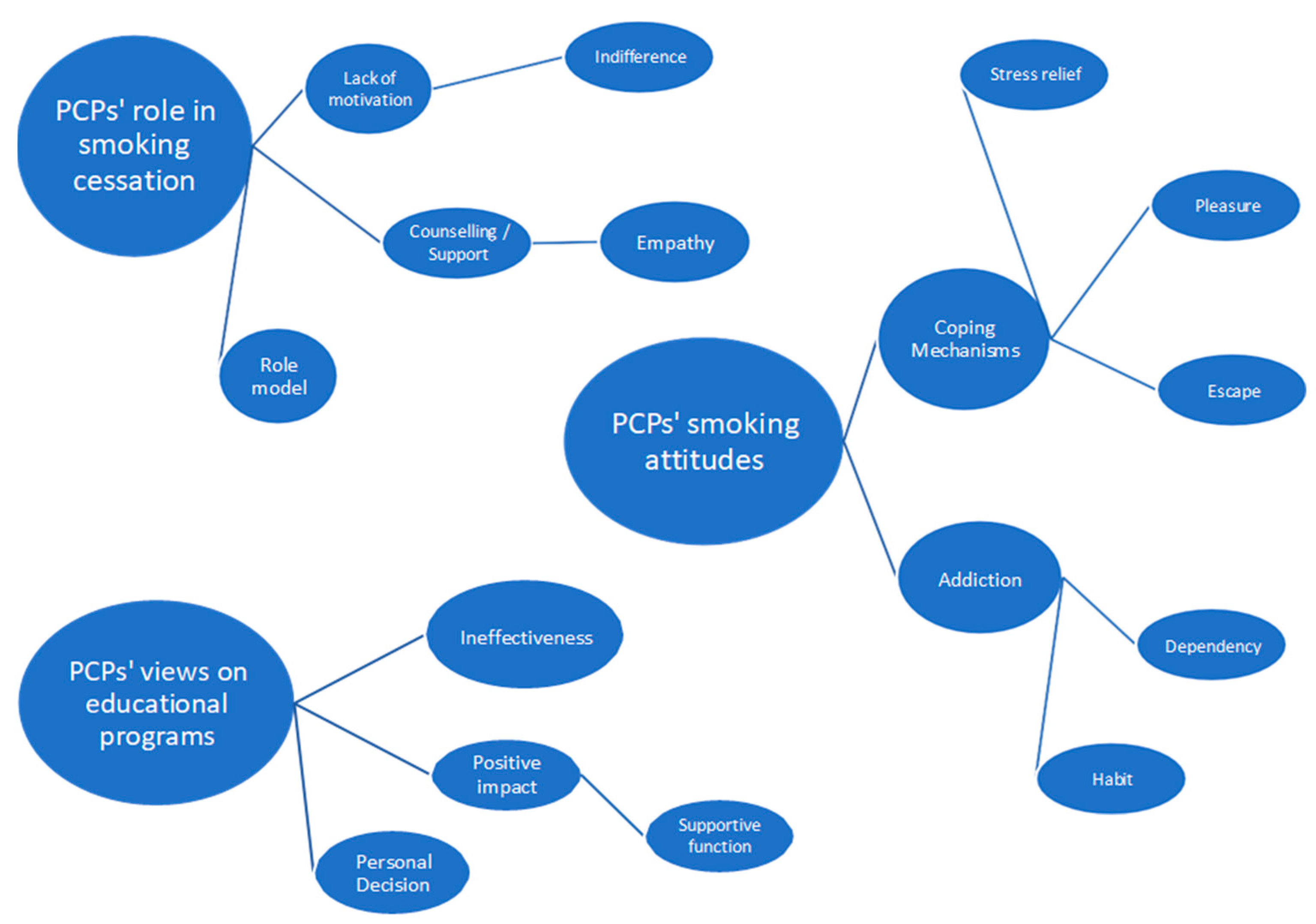

3. Results

- a.

- PCP’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors concerning their own smoking behavior.

- Coping mechanisms

- 1.

- Stress Relief

[...] “I feel that it helps, that I want it, especially after a difficult day in work it relieves me...”. GP, 30 years old, smoker.

[...] “Smoking two cigarettes at that moment (during stressful workload) helps me more. It takes away my stress. It helps me”. RN, 35 years old, smoker.

- 2.

- Pleasure

[...] “It is very pleasant as a habit, at least for me it was pleasant..I liked smoking and I remember that (smoking) was a happy moment during my stressful work”. RN, 40 years old, former smoker.

- 3.

- Escape

[...] “The reason I smoked was to escape from the problem that was bothering me. I was also utilizing it as a chance to get away from stressful tasks. It was something common among smokers colleagues” HV, 54 years, former smoker.

[...] “I also used it as a break. When you had a difficult task, you would say, ‘let me smoke a cigarette first to relax and then start’ or when you had to do some physical work, you would say, ‘okay, I’ll do it later’” GP, 40 years old, former smoker.

- Addiction

- 1.

- Tobacco dependence

[...] “It’s like a drug. It is a drug, not just like one, it is a drug. And that is the main reason that is so addictive” RN, 42 years old, smoker.

[...] “I consider cigarettes to be... yes, a drug. It’s a drug that provides pleasure.. And then is like a prison and you cannot escape”. GP, 53 years old, smoker.

- 2.

- Habit

[...] “The daily habit... the habit, I believe Because I am smoking during certain circumstances in my daily life. For example, I cannot drink a coffee without smoking a cigarette”. RN, 55 years old, smoker.

[...] “and the routine, where you do the same things, like getting up in the morning, eating, having your cigarette. It’s part of your routine …”. RN, 40 years old, former smoker.

- b.

- PCP’s attitudes and actions in supporting patients who smoke

- Role model

[...] “You are a role model. You can’t smoke like a chimney and tell a patient, ‘Yes, I smoke, but you should quit,’ especially if the patient is healthy and only coming for a check-up”. GP, 40 years old, non-smoker.

[...] “Now I can tell patients with more certainty that they should quit smoking. Before, I hesitated because I was a smoker myself”. RN, 51 years old, former smoker.

[...] “If the topic comes up, I mention that I smoke. However, I explain that it’s not right, and although I do it, it’s my mistake. But I still advise them to quit or at least reduce it”. RN, 35 years old, smoker.

[...] “I have never lied about it. Why should I say, ‘No, I don’t smoke,’ when I actually do? We’re in the healthcare field, but I’m not the only smoker”. RN, 40 years old, smoker.

[...] “I try to hide my cigarette pack. If it falls out, I feel ashamed”. RN, 56 years old, smoker.

[...] “If asked, I say I don’t smoke. Regardless of my personal beliefs, I must tell patients what medical science says”. GP, 40 years old, smoker.

- Lack of motivation to help patients who smoke

- 1.

- Indifference

[...] “I wouldn’t have the inclination or the strength to engage much in trying to persuade them because I would think, ‘Why should I care? I’m a smoker too.’” RN, 55 years old, smoker.

[...] “A nurse who smokes wouldn’t get involved in this matter regarding the patient. They wouldn’t make any comments on it”. RN, 56 years old, smoker.

- Counseling/Support

[...] “They (the PCPs) know the negative effects of smoking, and that’s why they will advise the patient based on their scientific knowledge that it is not good to smoke and that it is better to quit”. GP, 31 years old, non-smoker.

[...] “I believe I would encourage them more because I know what it means to want to quit and something is holding you back, so I think I would help encourage them”. RN, 41 years old, smoker.

- Empathy

[...] “I feel that I can talk to them a bit more, and maybe I’m more satisfied now when I tell them they need to quit smoking because I can say that I managed to quit”. GP, 40 years old, former smoker.

[...] “A former smoker who has tried to quit understands the difficulty and can advise and empathize with the patient, the smoker, and can offer tips, so to speak. We all know some general things, but it is different when you have experienced it”. RN, 55 years old, former smoker.

- c.

- PCPs’ views on the effectiveness of educational programs on smoking cessation

- Ineffectiveness

[...] ”I think it won’t affect me much. So, attending an educational program that tells me about the disadvantages of smoking and the consequences, the harmful consequences and so on, as I told you before, we know much better than anyone else”. RN, 46 years old, smoker.

[...] ”I believe it will not help in anything. It’s my issue, so if I want to quit, I will quit, no one else will influence me”. RN, 42 years old, smoker.

- Personal decision

[...] ”I really don’t know. It’s how much the other person wants to quit. I think that’s where the help is, regardless of if he is a healthcare professional” GP, 31 years old, smoker.

[...] ”Now how to motivate the healthcare professional himself is a bit difficult, it’s a bit of a decision he must take on his own, I think he knows the risks as a healthcare professional”. GP, 30 years old, smoker.

- Positive Impact

- 1.

- Supportive function

[...] “I believe everyone who smokes wants to quit at some point. They seek motivation, and through programs, they can find it”. RN, 51 years old, non-smoker.

[...] “A new horizon opens up, and to pass it on to the patient, you might try it yourself. To see if it works. Personally, it might influence me, providing knowledge or tools I could use myself”. RN, 40 years old, smoker.

[..] “They are parallel. And I think if I attended educational... as in other fields, every piece that enters opens another door for you; a window? A balcony door? The roof goes away and you see something else. Another light and gives you another perspective”. RN, 55 years old, smoker.

[...] “I think they help. Initially, I wasn’t convinced. Maybe it was too early, or I wasn’t ready, but I think they play a role and help”. RN, 40 years old, smoker.

[...] “It would help. Being around others with the same problem would be beneficial”. RN, 56 years old, smoker.

4. Discussion

- a.

- Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCP | Primary Care Provider |

| RN | Registered Nurses |

| GP | General Practitioners |

| HV | Health Visitors |

References

- Health Canada. Tobacco-Reports and Publications. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/reports-and-publications/tobacco/index.html (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- WHO. Tobacco: Health Effects 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- Papadakis, S.; Anastasaki, M.; Papadakaki, M.; Antonopoulou, M.; Chliveros, C.; Daskalaki, C.; Varthalis, D.; Triantafyllou, S.; Vasilaki, I.; McEwen, A.; et al. “Very Brief Advice” (VBA) on Smoking in Family Practice: A Qualitative Evaluation of the Tobacco User’s Perspective. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dannapfel, P.; Bendtsen, P.; Bendtsen, M.; Thomas, K. Implementing Smoking Cessation in Routine Primary Care—A Qualitative Study. Front. Health Serv. 2023, 3, 1201447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grech, J.; Sammut, R.; Buontempo, M.B.; Vassallo, P.; Calleja, N. Brief Tobacco Cessation Interventions: Practices, Opinions, and Attitudes of Healthcare Professionals. Tob. Prev. Cessat. 2020, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Cantera, C.; Sanmartín, J.M.I.; Martínez, A.F.; Lorenzo, C.M.; Cohen, V.B.; Jiménez, M.L.C.; Pérez-Teijón, S.C.; i Osca, J.A.R.; García, R.C.; Fernández, J.L.; et al. Good Practice Regarding Smoking Cessation Management in Spain: Challenges and Opportunities for Primary Care Physicians and Nurses. Tob. Prev. Cessat. 2020, 6, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardavas, C.I.; Bouloukaki, I.; Linardakis, M.K.; Tzilepi, P.; Tzanakis, N.; Kafatos, A.G. Smoke-Free Hospitals in Greece: Personnel Perceptions, Compliance and Smoking Habit. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2009, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardavas, C.I.; Kafatos, A.G. Smoking Policy and Prevalence in Greece: An Overview. Eur. J. Public Health 2007, 17, 211–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, K.; Nagelhout, G.E.; Fong, G.T.; Vardavas, C.I.; Papadakis, S.; Herbeć, A.; Mons, U.; Van Den Putte, B.; Borland, R.; Fernández, E.; et al. Quitting Activity and Use of Cessation Assistance Reported by Smokers in Eight European Countries: Findings from the EUREST-PLUS ITC Europe Surveys. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2018, 16, A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.; Tam, J.; Kuo, C.; Fong, G.; Chaloupka, F. The Impact of Implementing Tobacco Control Policies: The 2017 Tobacco Control Policy Scorecard. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2018, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatopoulou, E.; Stamatiou, K.; Voulioti, S.; Christopoulos, G.; Pantza, E.; Stamatopoulou, A.; Giannopoulos, D. Smoking Behavior among Nurses in Rural Greece. Workplace Health Saf. 2014, 62, 132–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamanti, A.; Galiatsatou, A.; Sarantaki, A.; Katsaounou, P.; Varnakioti, D.; Lykeridou, A. Barriers to Smoking Cessation and Characteristics of Pregnant Smokers in Greece. Maedica 2021, 16, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, S.; Vardavas, C.; Katsaounou, P.; Smyrnakis, E.; Samoutis, G.; Lintovoi, E.; Tatsioni, A.; Tsiligianni, I.; Thireos, L.; Makaroni, S.; et al. National Scale-up of the TITAN Greece and Cyprus Primary Care Tobacco Treatment Training Network: Efficacy, Assets, and Lessons Learned. Tob. Prev. Cessat. 2022, 8, A37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, C.; Ferguson, S.G.; Nash, R. Barriers to Smoking Interventions in Community Healthcare Settings: A Scoping Review. Health Promot. Int. 2024, 39, daae036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stead, L.F.; Buitrago, D.; Preciado, N.; Sanchez, G.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Lancaster, T. Physician Advice for Smoking Cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD000165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Bolaños, R.; Ponciano-Rodríguez, G.; Rojas-Carmona, A.; Cartujano-Barrera, F.; Arana-Chicas, E.; Cupertino, A.P.; Reynales-Shigematsu, L.M. Practice, Barriers, and Facilitators of Healthcare Providers in Smoking Cessation in Mexico. Enfermería Clín. 2022, 32, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyahen, E.O.; Omoruyi, O.O.; Rowa-Dewar, N.; Dobbie, F. Exploring the Barriers and Facilitators to the Uptake of Smoking Cessation Services for People in Treatment or Recovery from Problematic Drug or Alcohol Use: A Qualitative Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puffer, S.; Rashidian, A. Practice Nurses’ Intentions to Use Clinical Guidelines. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 47, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in Qualitative Research: Exploring Its Conceptualization and Operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlett, C.P. Social Psychology Theory Extensions. In Predicting Cyberbullying; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A New Method for Characterising and Designing Behaviour Change Interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rossem, C.; Spigt, M.G.; Kleijsen, J.R.C.; Hendricx, M.; Van Schayck, C.P.; Kotz, D. Smoking Cessation in Primary Care: Exploration of Barriers and Solutions in Current Daily Practice from the Perspective of Smokers and Healthcare Professionals. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2015, 21, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellali, T. Criteria and Processes for Evaluating Qualitative Research Methodology in Health Studies. Arch. Hell. Med. 2006, 23, 378–384. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, D.; Hoffman, A.; Ael, D.; Orlowski, J.M. Understanding People Who Smoke and How They Change: A Foundation for Smoking Cessation in Primary Care, Part 1. Disease-a-Month 2002, 48, 390–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pipe, A.; Sorensen, M.; Reid, R. Physician Smoking Status, Attitudes toward Smoking, and Cessation Advice to Patients: An International Survey. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 74, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarna, L.; Bialous, S.A.; Nandy, K.; Antonio, A.L.M.; Yang, Q. Changes in Smoking Prevalences among Health Care Professionals from 2003 to 2010–2011. JAMA 2014, 311, 197–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriaenssens, J.; De Gucht, V.; Maes, S. Causes and Consequences of Occupational Stress in Emergency Nurses, a Longitudinal Study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2015, 23, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippidis, F.T.; Vardavas, C.I.; Loukopoulou, A.; Behrakis, P.; Connolly, G.N.; Tountas, Y. Prevalence and Determinants of Tobacco Use among Adults in Greece: 4 Year Trends. Eur. J. Public Health 2013, 23, 772–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tong, E.K.; Strouse, R.; Hall, J.; Kovac, M.; Schroeder, S.A. National Survey of U.S. Health Professionals’ Smoking Prevalence, Cessation Practices, and Beliefs. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2010, 12, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson Miller, J.; Hartman, T.K.; Levita, L.; Martinez, A.P.; Mason, L.; McBride, O.; McKay, R.; Murphy, J.; Shevlin, M.; Stocks, T.V.A.; et al. Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation to Enact Hygienic Practices in the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Outbreak in the United Kingdom. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koomen, L.E.M.; Deenik, J.; Cahn, W. The Association between Mental Healthcare Professionals’ Personal Characteristics and Their Clinical Lifestyle Practices: A National Cross-Sectional Study in The Netherlands. Eur. Psychiatry 2023, 66, e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berjawi, A.; Nasser, M.; Nassreddine, W.; Kanj, A.; Kojok, A.; Kanj, N. A Cross-Sectional Study of the Alarming Prevalence of Smoking Among Lebanese Physicians and Its Negative Impact on Promoting Cessation. Int. J. Clin. Res. 2021, 2, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, M.; Jaen, C.; Baker, T. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Rockville, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh, L.K.; Saunders, J.M.; Cassell, J.; Bastaki, H.; Hartney, T.; Rait, G. Facilitators and Barriers to Chlamydia Testing in General Practice for Young People Using a Theoretical Model (COM-B): A Systematic Review Protocol. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.S.; Bawany, F.I.; Ahmed, M.U.; Hussain, M.; Bukhari, N.; Nisar, N.; Khan, M.; Raheem, A.; Arshad, M.H. The Frequency of Smoking and Common Factors Leading to Continuation of Smoking among Health Care Providers in Tertiary Care Hospitals of Karachi. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2014, 6, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pazarli Bostan, P.; Karaman Demir, C.; Elbek, O.; Akçay, Ş. Association between Pulmonologists’ Tobacco Use and Their Effort in Promoting Smoking Cessation in Turkey: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2015, 15, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alateeq, M.; Alrashoud, A.M.; Khair, M.; Salam, M. Smoking Cessation Advice: The Self-Reported Attitudes and Practice of Primary Health Care Physicians in a Military Community, Central Saudi Arabia. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2016, 10, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dickerson, F.; Goldsholl, S.; Yuan, C.T.; Dalcin, A.; Eidman, B.; Minahan, E.; Gennusa, J.V.; Mace, E.; Cullen, B.; Evins, A.E.; et al. Promoting Evidence-Based Tobacco Cessation Treatment in Community Mental Health Clinics: Protocol for a Prepost Intervention Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2023, 12, e44787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dineen-Griffin, S.; Garcia-Cardenas, V.; Williams, K.; Benrimoj, S.I. Helping Patients Help Themselves: A Systematic Review of Self-Management Support Strategies in Primary Health Care Practice. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.L.; Adkins, D.; Chauvin, S. A Review of the Quality Indicators of Rigor in Qualitative Research. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 84, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Profession | Smoking Status | Gender | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nurse | Non smoker | Female | 54 |

| 2 | Nurse | Smoker | Female | 56 |

| 3 | Nurse | Smoker | Female | 55 |

| 4 | Physician | Non smoker | Female | 31 |

| 5 | Nurse | Former smoker | Female | 51 |

| 6 | Physician | Smoker | Male | 30 |

| 7 | Nurse | Smoker | Female | 46 |

| 8 | Nurse | Smoker | Female | 42 |

| 9 | Physician | Smoker | Male | 66 |

| 10 | Nurse | Former smoker | Female | 55 |

| 11 | Health Visitor | Former smoker | Female | 54 |

| 12 | Physician | Smoker | Female | 65 |

| 13 | Physician | Former smoker | Female | 40 |

| 14 | Nurse | Smoker | Female | 55 |

| 15 | Nurse | Smoker | Female | 40 |

| 16 | Nurse | Non smoker | Female | 52 |

| 17 | Nurse | Smoker | Female | 40 |

| 18 | Nurse | Smoker | Female | 41 |

| 19 | Physician | Non smoker | Female | 40 |

| 20 | Physician | Smoker | Male | 53 |

| 21 | Nurse | Smoker | Female | 35 |

| 22 | Nurse | Non smoker | Female | 55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stafylidis, S.; Papadakis, S.; Papamichail, D.; Lionis, C.; Smyrnakis, E. Perceptions and Experiences of Primary Care Providers on Their Role in Tobacco Treatment Delivery Based on Their Smoking Status: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2500. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12242500

Stafylidis S, Papadakis S, Papamichail D, Lionis C, Smyrnakis E. Perceptions and Experiences of Primary Care Providers on Their Role in Tobacco Treatment Delivery Based on Their Smoking Status: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare. 2024; 12(24):2500. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12242500

Chicago/Turabian StyleStafylidis, Stavros, Sophia Papadakis, Dimitris Papamichail, Christos Lionis, and Emmanouil Smyrnakis. 2024. "Perceptions and Experiences of Primary Care Providers on Their Role in Tobacco Treatment Delivery Based on Their Smoking Status: A Qualitative Study" Healthcare 12, no. 24: 2500. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12242500

APA StyleStafylidis, S., Papadakis, S., Papamichail, D., Lionis, C., & Smyrnakis, E. (2024). Perceptions and Experiences of Primary Care Providers on Their Role in Tobacco Treatment Delivery Based on Their Smoking Status: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare, 12(24), 2500. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12242500