Exploring the Impact of Personal Factors on Residents’ Willingness to Undergo Primary Care Initial Diagnosis in Beijing, China: A Mixed Methods Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

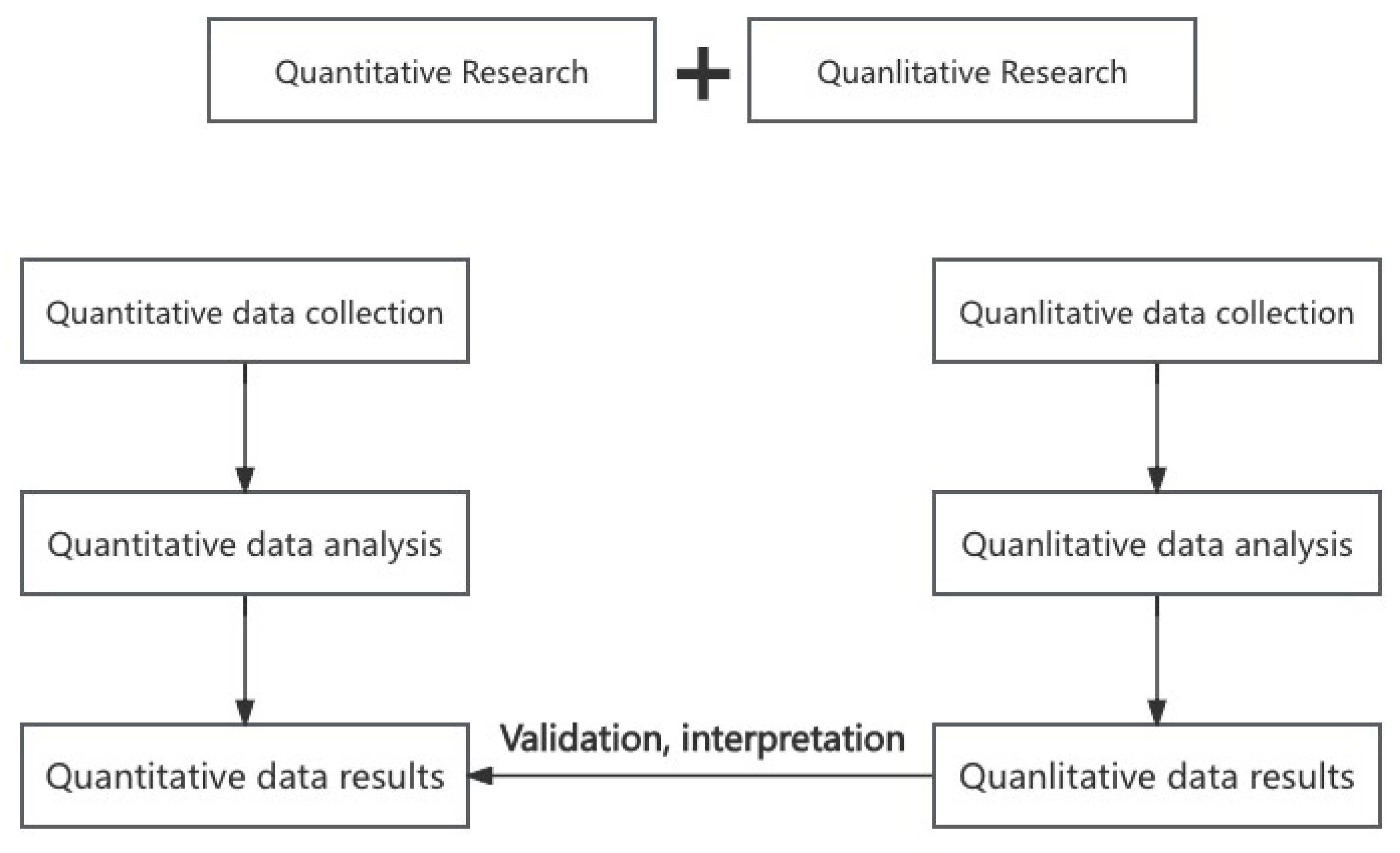

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection Tools

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Basic Information of Residents

3.2. Residents’ Attitudes Toward Primary Care Initial Diagnosis Policy

3.3. Residents Choose Hospital Level According to the Disease Type

3.4. Factor Analysis of Residents’ Willingness Regarding Primary Care Initial Diagnosis

3.5. Residents’ Views on Primary Care Initial Diagnosis

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings and Policy Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.; Chen, Z. Health-seeking behavior and patient welfare: Evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2023, 80, 102015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigler, F.L.; Macinko, J.; Pettigrew, L.M.; Kumar, R.; van Weel, C. No universal health coverage without primary health care. Lancet 2016, 387, 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Xu, H.; Du, F.; Zhu, B.; Xie, P.; Wang, H.; Han, X. Does increasing physician volume in primary healthcare facilities under the hierarchical medical system help reduce hospital service utilisation in China? A fixed-effects analysis using province-level panel data. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e066375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, S.; Ou, M.S.; Hong, R.W. Foreign family physician service model and its enlightenment on China. Heilongjiang Med. J. 2015, 39, 852–853. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, K.M.; Andersen, J.S.; Søndergaard, J. General practice and primary health care in Denmark. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. JABFM 2012, 25 (Suppl. S1), 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starfield, B. Primary Care and Health: A Cross-National Comparison. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1991, 226, 2268–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Lam, T.P. Underuse of primary care in China: The scale, causes, and solutions. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2016, 29, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Wang, L. Evaluation for hierarchical diagnosis and treatment policy proposals in China: A novel multi-attribute group decision-making method with multi-parametric distance measures. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2022, 37, 1089–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, W.; Fu, H.; Chen, A.; Zhai, T.; Jian, W.; Xu, R.; Pan, J.; Hu, M.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, Q.; et al. 10 years of health-care reform in China: Progress and gaps in universal health coverage. Lancet 2019, 394, 1192–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Shen, C.; Lai, S.; Nawaz, R.; Gao, J. Evaluating the effect of hierarchical medical system on health seeking behavior: A difference-in-differences analysis in China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 268, 113372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Ageing, 2019 Highlights; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Wang, R.; Li, H.; Han, S.; Shen, P.; Lin, H.; Guan, X.; Shi, L. Effectiveness of hierarchical medical system policy: An interrupted time series analysis of a pilot scheme in China. Health Policy Plan. 2023, 38, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, D.; Mei, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, P.; Yang, X.; Huang, J. Building a people-centred integrated care model in Urban China: A qualitative study of the health reform in Luohu. Int. J. Integr. Care 2020, 20, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Hao, H.; Wang, J.; Nicholas, S. Impact of hierarchical hospital reform on patients with diabetes in China: A retrospective observational analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e041731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Ramesh, M. Strengthening primary health care in China: Governance and policy challenges. Health Econ. Policy Law 2024, 19, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Fu, H. China’s health care system reform: Progress and prospects. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2017, 32, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, L.; Qing, K.; Sha, Y.; Van de Klundert, J. Factors influencing choice of health system access level in China: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201887. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, S.; Fang, W.; Ci, D.; Tian, M.M.; Jia, M.; Zhao, M.J. Influencing factors on residents’ behavior about family doctor contracting service and first-contact at primary care. Chin. J. Health Policy 2020, 13, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Zhang, B. Hierarchical medical, primary diagnosis and construction of primary medical and health institutions. Xuehai 2016, 2, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Q. Strategic selection to promote the establishment of hierarchical medical model. China Health Econ. 2015, 2, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Lu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, D. Analysis of primary care initial diagnosis and referral willingness of urban and rural residents in primary medical institutions in Shandong Province. Chin. Public Health 2021, 37, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Skilled doctors in tertiary hospitals are already overworked in China. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, e737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, Y.; Shan, L.; Jing, J. System thinking and advice of hierarchical medical services. Chin. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 36, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Tong, X.; Zhang, A.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Y. Research on the impact of patient trust model and level on first-diagnosis willingness at the grassroots level. Chin. Health Policy Res. 2021, 14, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.; Deng, S. Current status, problems and development suggestions of chronic disease management in my country. Chin. Health Policy Res. 2016, 9, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Ai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C. Analysis of Influencing Factors on Cognitive Bias of Rural Residents’ First Visit to Primary Care. Health Econ. Res. 2024, 9, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Bing, L.; Feng, H.; Yue, L.; Wang, B. Researches on the Factors to Influence the Community Residents’ Medical Behaviors under the Background of Hierarchical Diagnosis and Treatment System. Chin. Health Serv. Manag. 2023, 40, 741–744. [Google Scholar]

- Han, C.; Yu, L.; Jin, J.; Lv, Y. Research on the willingness and influencing factors of the first medical visit of the floating population at the grassroots level in the context of hierarchical medical system. Chin. Hosp. 2023, 27, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Deng, J. Effects of and Prospects for the Hierarchical Medical Policy in Beijing, China. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, C.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Ma, S. Limited effects of the comprehensive pricing healthcare reform in China. Public Health 2019, 175, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.; Tang, D.; Xu, A. Attribute-Driven or Green-Driven: The Impact of Subjective and Objective Knowledge on Sustainable Tea Consumption. Foods 2023, 12, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Yang, J. Study on the willingness and influencing factors of primary care initial diagnosis and two-way referral of patients in hospitals at different levels in Beijing. Chin. Hosp. 2020, 24, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Koopmann, J.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Liu, S. Job search self-regulation during COVID-19: Linking search constraints, health concerns, and invulnerability to job search processes and outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 106, 975–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuyen, V.; Altyn, A.; Gaukhar, B.; Pham, T.V.; Pham, K.M.; Truong, T.Q.; Nguyen, K.T.; Oo, W.M.; Mohamad, E.; Su, T.T.; et al. Measuring health literacy in Asia: Validation of the HLS-EU-Q47 survey tool in six Asian countries. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 27, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kristine, S.; Stephan, V.; Jurgen, M.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Slonska, Z.; Kondilis, B.; Stoffels, V.; Osborne, R.H.; Brand, H. Measuring health literacy in populations: Illuminating the design and development process of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q). BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 948. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Ye, X.; Zhen, C.; Zuo, X.; Wang, T.; Guan, Z.; Meng, K. Study on patients’ primary care initial diagnosis willingness and influencing factors within Beijing Medical Consortium. Chin. Health Policy Res. 2018, 11, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, R.; Chen, S.; Qiao, X.; Zhang, X. Systematic evaluation of the current situation and effect of the primary care initial diagnosis system in China. Health Soft Sci. 2020, 34, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Yin, W.; Yan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, C. Meta-analysis of residents’ willingness to receive first diagnosis in primary medical institutions in China. Chin. J. Evid.-Based Med. 2021, 21, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, T. Analysis of factors influencing the migrant population’s willingness to settle down. Popul. Soc. 2016, 32, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, F.; Li, C.; Ge, J.; Luo, B. A review of research on user feature request analysis and processing. J. Softw. 2023, 3, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi, D.M.; Alam, I.; Anzum, M. An Empirical Investigation of Consumers’ Intention for Using Ride-Sharing Applications: Does Perceived Risk Matter? Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2021, 18, 2150040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, S.; Zhou, G. User continuance of a green behavior mobile application in China: An empirical study of Ant Forest. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118497.1–118497.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhao, L.; Liang, J.; Qiao, Y.; He, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, F.; Liang, Y. Societal determination of usefulness and utilization wishes of community health services: A population-based survey in Wuhan city, China. Health Policy Plan. 2015, 30, 1243–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vainieri, M.; Vandelli, A.; Benvenuti, S.; Bertarelli, G. Tracking the digital health gap in elderly: A study in Italian remote area. Health Policy 2023, 133, 104842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anna, S.; Iwona, K.B.; Katarzyna, B.M.; Gałązka-Sobotka, M. A reform proposal from 2019 aims to improve coordination of health services in Poland by strengthening the role of the counties. Health Policy 2022, 126, 837–843. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Kong, X.; Zhao, L.; Chen, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xu, X. Survey on primary care initial diagnosis willingness and attitude of non-emergency patients in tertiary hospitals. Mod. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 18, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- An, R.; Qin, L.; Yang, X.; Guo, J. Analysis of influencing factors on primary care initial diagnosis willingness of urban and rural residents’ basic medical insurance participants in Guangdong Province. Med. Soc. 2022, 35, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, R.; Fu, Q. Survey on the current situation of primary patient diagnosis in a compact medical consortium under a grid management layout. Chin. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 10, 042. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Miao, C.; Hu, C.; Xu, J.; Zheng, J. Research on the current situation and influencing factors of grassroots medical treatment for chronic disease patients in Xuzhou under the background of hierarchical medical policy. Mod. Prev. Med. 2020, 47, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, X. Analysis of factors affecting primary care initial diagnosis and family doctor contracting for elderly patients with chronic diseases in Kunming. Med. Soc. 2021, 34, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, Z.; Yang, S.; Yan, C.; Li, W. The impact of family doctor contract services on the choice of first diagnosis institution for chronic disease patients in Shandong. China Health Resour. 2022, 25, 101–105+125. [Google Scholar]

| Item | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 304 | 49.8 |

| Female | 306 | 50.2 |

| Age | ||

| 20 years old and below | 1 | 0.2 |

| 21 to 30 years old | 147 | 24.1 |

| 31 to 40 years old | 334 | 54.8 |

| 41 to 50 years old | 121 | 19.8 |

| 51 to 60 years old | 7 | 1.1 |

| Education level | ||

| High school and below | 59 | 9.7 |

| Junior college | 115 | 18.9 |

| Undergraduate | 383 | 62.8 |

| Postgraduate | 53 | 8.7 |

| Insurance type | ||

| Basic medical insurance for urban employees | 459 | 75.2 |

| Basic medical insurance for urban residents | 74 | 12.1 |

| New rural co-operative medical insurance | 37 | 6.1 |

| Commercial health insurance | 28 | 4.6 |

| Public-funded medical service insurance | 12 | 2.0 |

| Occupation | ||

| Peasantry | 12 | 2.0 |

| Employees of enterprises and public institutions | 504 | 82.6 |

| Self-employed | 52 | 8.5 |

| Emeritus and retired | 1 | 0.2 |

| Freelancer | 29 | 4.8 |

| Unemployed | 12 | 2.0 |

| Have a chronic disease | ||

| Yes | 128 | 21.0 |

| No | 482 | 79.0 |

| Disease Type | Community Health Service Center | Primary Hospital | Secondary Hospital | Tertiary Hospital | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Common disease | 493 | 80.8 | 94 | 15.4 | 13 | 2.1 | 10 | 1.6 |

| Acute disease | 2 | 0.3 | 144 | 23.6 | 274 | 44.9 | 190 | 31.1 |

| Chronic disease | 14 | 2.3 | 134 | 22.0 | 405 | 66.4 | 57 | 9.3 |

| Severe disease | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.3 | 96 | 15.7 | 512 | 83.9 |

| Difficult miscellaneous disease | 2 | 0.3 | 9 | 1.5 | 97 | 15.9 | 502 | 82.3 |

| Recover after illness | 187 | 30.7 | 247 | 40.5 | 149 | 24.4 | 27 | 4.4 |

| Item | Mean | SD | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 33.101 | 0.000 | ||

| Male | 4.48 | 0.703 | ||

| Female | 4.12 | 0.820 | ||

| Age | 5.174 | 0.000 | ||

| 20 years old and below | 4.00 | - | ||

| 21 to 30 years old | 4.10 | 0.894 | ||

| 31 to 40 years old | 4.35 | 0.743 | ||

| 41 to 50 years old | 4.45 | 0.695 | ||

| 51 to 60 years old | 3.71 | 0.756 | ||

| Education level | 8.797 | 0.000 | ||

| High school and below | 4.37 | 0.786 | ||

| Junior college | 4.29 | 0.825 | ||

| Undergraduate | 4.37 | 0.739 | ||

| Postgraduate | 3.79 | 0.840 | ||

| Insurance type | 1.163 | 0.326 | ||

| Basic medical insurance for urban employees | 4.31 | 0.780 | ||

| Basic medical insurance for urban residents | 4.36 | 0.823 | ||

| New rural co-operative medical insurance | 4.30 | 0.661 | ||

| Commercial health insurance | 4.07 | 0.766 | ||

| Public-funded medical service insurance | 4.00 | 1.044 | ||

| Occupation | 0.985 | 0.426 | ||

| Peasantry | 4.50 | 0.798 | ||

| Employees of enterprises and public institutions | 4.32 | 0.772 | ||

| Self-employed | 4.21 | 0.800 | ||

| Emeritus and retired | 4.00 | - | ||

| Freelancer | 4.24 | 0.830 | ||

| Unemployed | 3.92 | 1.084 | ||

| Have a chronic disease | 0.467 | 0.495 | ||

| Yes | 4.34 | 0.818 | ||

| No | 4.29 | 0.776 |

| Influencing Factors | Mean | Beta | SD | S Beta | t | p | 95% Confidence Interval for Beta | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Limit | Lower Limit | |||||||

| (Constant) | −1.053 | 0.377 | −2.790 | 0.000 | −1.794 | −0.312 | ||

| State of an illness | 4.577 | −0.048 | 0.044 | −0.034 | −1.095 | 0.274 | −0.133 | 0.038 |

| Level of confidence in the government | 4.248 | 0.320 | 0.037 | 0.316 | 8.570 | 0.000 | 0.246 | 0.393 |

| Satisfaction with previous health reform policies | 4.423 | −0.008 | 0.039 | −0.007 | −0.213 | 0.832 | −0.086 | 0.069 |

| Personal health status | 4.074 | 0.276 | 0.037 | 0.265 | 7.462 | 0.000 | 0.203 | 0.349 |

| Health literacy | 3.254 | 0.468 | 0.115 | 0.204 | 4.065 | 0.000 | 0.242 | 0.694 |

| E-Health literacy | 4.313 | −0.247 | 0.112 | −0.161 | −2.206 | 0.028 | −0.466 | −0.027 |

| Level of trust in Internet medical care | 3.951 | 0.587 | 0.206 | 0.280 | 2.851 | 0.005 | 0.183 | 0.992 |

| Interviewee | Gender | Age | Interview Transcripts |

|---|---|---|---|

| R 1 | Female | 70 | Occasionally, I opt for medical services at a community health service center, but I must admit that some of my experiences have been unsatisfactory. Despite the center’s modest size, I did not find it very convenient to seek treatment, which sometimes deters me from choosing it as my primary option. |

| R 2 | Male | 32 | Personally, I’m aware of the primary care initial diagnosis policy and I’m willing to implement it. However, I don’t know enough about the health service center in my community, so sometimes I would rather go to a tertiary hospital, even though it is more troublesome. |

| R 3 | Male | 36 | In my opinion, with the implementation of the primary care initial diagnosis policy, patients with common diseases are more willing to choose the nearest community health service centers for treatment. |

| R 4 | Female | 52 | I have been suffering from a chronic illness and have been prescribed drugs and treatment at a tertiary hospital for the last few years, which is a more regular form of medical treatment for me. There are two community health centers near me, but they don’t have the drugs I need, so I have to go to the tertiary hospital. |

| R 5 | Male | 66 | I have sought treatment at both community health service centers and tertiary hospitals. For chronic conditions, registering and explaining my situation to a new doctor each time can be cumbersome. I haven’t noticed many advantages at community health centers in managing chronic diseases. If there were clear benefits compared to tertiary hospitals, I would prefer to choose it. |

| R 6 | Male | 37 | For me, the government healthcare sector is the main player in promoting the implementation of policies. Therefore, I think that the government sector must give people hope and instill confidence in the residents, so that they will believe in the power of the primary care initial diagnosis policy. |

| R 7 | Male | 59 | Although I’m older, I usually keep up with my exercise, so my health is in good shape. When I have a minor issue such as a cold or fever, I believe in my body’s ability to recover and feel that the community health service centers can provide me with the treatment I need. |

| R 8 | Male | 30 | I usually get health information from the Internet to learn about diseases and treatments. When someone in my family gets sick, I make the first judgment call and can buy the medication myself for treatment. |

| R 9 | Female | 45 | The rapid development of the Internet has also accelerated the growth of the medical industry. I used to have to go to the hospital for medical treatment, but now I can diagnose through the Internet and then pick up the medication offline, which has brought great convenience to the patients. |

| R 10 | Female | 40 | Internet healthcare has not only resulted in fewer bills for patients, but in some cases, patients can even receive treatment without leaving their homes. This not only saves time but also reduces traveling expenses. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wu, Z.; Deng, W. Exploring the Impact of Personal Factors on Residents’ Willingness to Undergo Primary Care Initial Diagnosis in Beijing, China: A Mixed Methods Research. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2451. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232451

Gao Y, Guo Y, Wu Z, Deng W. Exploring the Impact of Personal Factors on Residents’ Willingness to Undergo Primary Care Initial Diagnosis in Beijing, China: A Mixed Methods Research. Healthcare. 2024; 12(23):2451. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232451

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Yongchuang, Yuangeng Guo, Zhennan Wu, and Wenhao Deng. 2024. "Exploring the Impact of Personal Factors on Residents’ Willingness to Undergo Primary Care Initial Diagnosis in Beijing, China: A Mixed Methods Research" Healthcare 12, no. 23: 2451. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232451

APA StyleGao, Y., Guo, Y., Wu, Z., & Deng, W. (2024). Exploring the Impact of Personal Factors on Residents’ Willingness to Undergo Primary Care Initial Diagnosis in Beijing, China: A Mixed Methods Research. Healthcare, 12(23), 2451. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232451