Pregnant Women’s Awareness of Periodontal Disease Effects: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Study in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of the Study

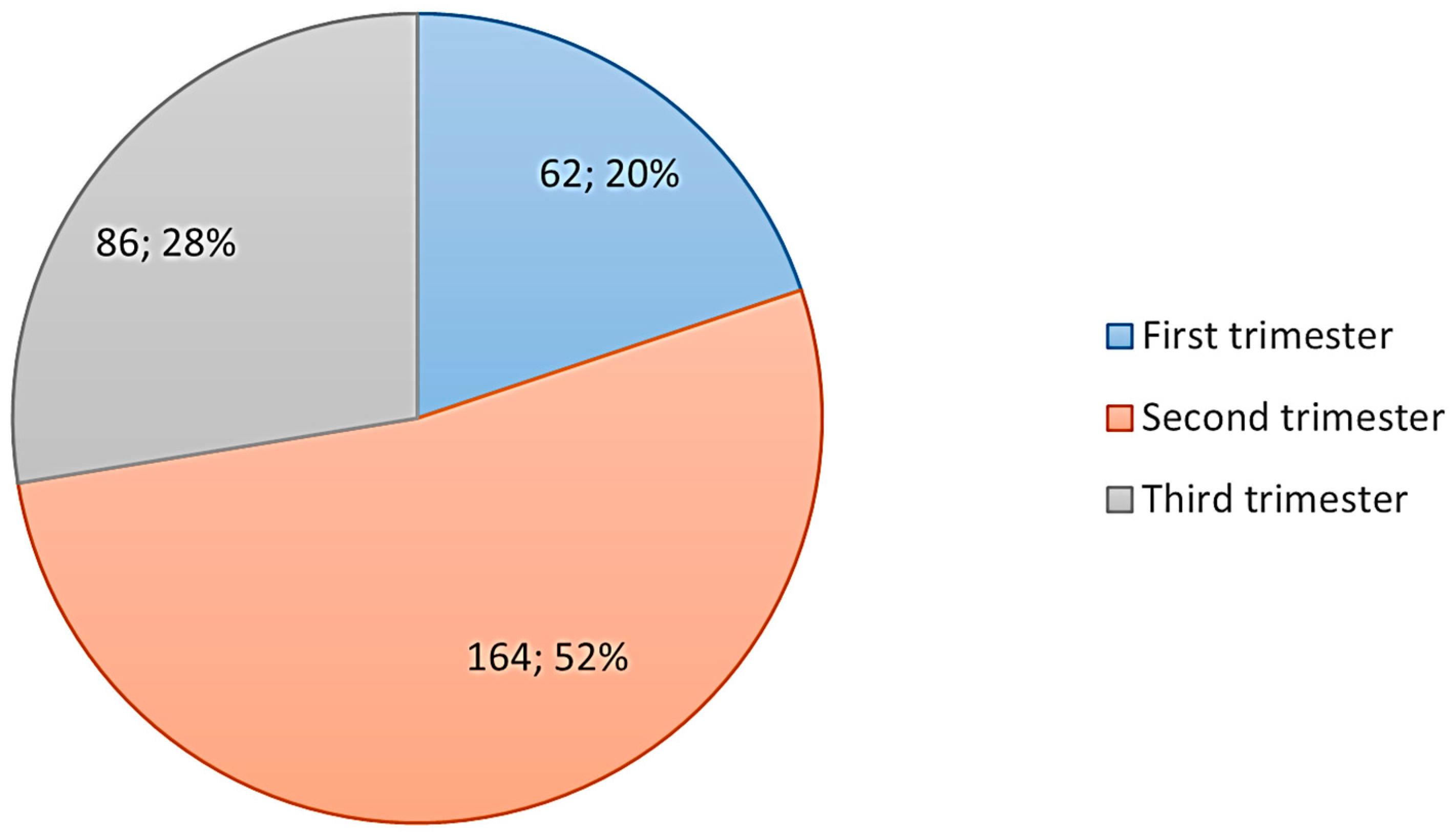

2.2. Study Participants

- a.

- Pregnant women who were unable to communicate effectively in Arabic or English, as the study materials were only available in these languages.

- b.

- Pregnant women with severe mental illnesses, as this might affect their ability to understand the study’s aim and scope.

- c.

- Pregnant women who declined to provide informed consent.

- d.

- Women who were postpartum or had ectopic pregnancies.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Instrument

2.6. Analysis of Statistics

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ilyosovna, Y.S.; Sergeyevich, L.N.; Baxodirovich, A.B.; Rustamovich, I.I. Pathogenesis of periodontal diseases caused by dental plaque. Multidiscip. J. Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 273–277. [Google Scholar]

- Łasica, A.; Golec, P.; Laskus, A.; Zalewska, M.; Gędaj, M.; Popowska, M. Periodontitis: Etiology, conventional treatments, and emerging bacteriophage and predatory bacteria therapies. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1469414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neurath, N.; Kesting, M. Cytokines in gingivitis and periodontitis: From pathogenesis to therapeutic targets. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1435054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muxammadjonovna, B.U.; Sheraliyevich, S.S.; Firdavsiyevich, R.J. Diagnosis and treatment of periodontal diseases. Multidiscip. J. Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 268–272. [Google Scholar]

- Arshad, S.; Awang, R.A.; Rahman, N.A.; Hassan, A.; Ahmad, W.M.A.W.; Mohamed, R.N.; Basha, S.; Karobari, M.I. Assessing the impact of systemic conditions on periodontal health in Malaysian population: A retrospective study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihlstrom, B.L.; Michalowicz, B.S.; Johnson, N.W. Periodontal diseases. Lancet 2005, 366, 1809–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, A.; Paladini, S.; Cossatis, J. Periodontal Disease and Alzheimer’s: Insights from a Systematic Literature Network Analysis. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2024, 11, 1148–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirnic, J.; Djuric, M.; Brkic, S.; Gusic, I.; Stojilkovic, M.; Tadic, A.; Veljovic, T. Pathogenic Mechanisms That May Link Periodontal Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus—The Role of Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, G.C. Periodontal diagnoses and classification of periodontal diseases. Periodontology 2000 2004, 34, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, P.; Mittal, N. Periodontal diseases-a brief review. Int. J. Oral Health Dent. 2020, 6, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzic, M.; Aimagambetova, G.; Terzic, S.; Radunovic, M.; Bapayeva, G.; Laganà, A.S. Periodontal pathogens and preterm birth: Current knowledge and further interventions. Pathogens 2021, 10, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, A.; Shamim, S.; Johnson, M.; Ajwani, S.; Bhole, S.; Blinkhorn, A.; Ellis, S.; Andrews, K. Periodontal treatment during pregnancy and birth outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomised trials. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2011, 9, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nannan, M.; Xiaoping, L.; Ying, J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy and adverse pregnancy outcomes: Progress in related mechanisms and management strategies. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 963956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.B.; Batra, S.; Halemani, S.; Rao, A.G.; Agarwal, M.C.; Gajjar, S.K.; Kakkad, D. Maternal Periodontitis Prevalence and its Relationship with Preterm and Low-Birth Weight Infants: A Hospital-Based Research. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2024, 16 (Suppl. 1), S488–S491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño-Suárez, L.; Paternina-Mejía, G.Y.; Vásquez-Olmos, L.D.; Rodríguez-Medina, C.; Botero, J.E. Linking Periodontitis to Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: A Comprehensive Review and Meta-analysis. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2024, 11, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalowicz, B.S.; Gustafsson, A.; Thumbigere-Math, V.; Buhlin, K. The effects of periodontal treatment on pregnancy outcomes. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, S195–S208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, J.; Tang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, F.; Yu, D.; Li, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, B.; Wu, W. Effects of different periodontal interventions on the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in pregnant women: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1373691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambrone, L.; Guglielmetti, M.R.; Pannuti, C.M.; Chambrone, L.A. Evidence grade associating periodontitis to preterm birth and/or low birth weight: I. A systematic review of prospective cohort studies. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2011, 38, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Wang, M.; Hu, B.; Qu, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, Q. The global burden of periodontal diseases in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 754–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachelarie, L.; Iman, A.E.H.; Romina, M.V.; Huniadi, A.; Hurjui, L.L. Impact of Hormones and Lifestyle on Oral Health During Pregnancy: A Prospective Observational Regression-Based Study. Medicina 2024, 60, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanto, A.; Bawono, C.A.; Putri, S.S. Hormonal changes as the risk factor that modified periodontal disease in pregnant women: A systematic review. J. Int. Oral Health 2024, 16, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktarina, O.; Tumaji, T.; Roosihermiatie, B.; Ulfa, Y.; Afifah, T.; Irianto, J.; Rachmat, B. Factors related to periodontal diseases among pregnant women: A national cross-sectional study in Indonesia. J. Popul. Soc. Stud. [JPSS] 2025, 33, 472–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, S.; Mallick, R.; Navya Sree, B.; Duttaroy, A.K. Placental Epigenome Impacts Fetal Development: Effects of Maternal Nutrients and Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velosa-Porras, J.; Rodríguez Malagón, N. Perceptions, knowledge, and practices related to oral health in a group of pregnant women: A qualitative study. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2024, 10, e823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amriddinovna, S.S.; Baxtiyor, S.; Jasur, R.; Shaxriyor, U. Therapeutic and preventive measures for periodontal diseases in pregnant women. Web Med. J. Med. Pract. Nurs. 2024, 2, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhurayji, K.S.; Al Suwaidan, H.; Kalagi, F.; Al Essa, M.; Alsubaie, M.; Alrayes, S.; Althumairi, A. Perception of Periodontitis Patients about Treatment Outcomes: A Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagetti, M.G.; Salerno, C.; Ionescu, A.C.; La Rocca, S.; Camoni, N.; Cirio, S.; Campus, G. Knowledge and attitudes on oral health of women during pregnancy and their children: An online survey. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammulle, K.A.; Dhanapriyanka, M.; Bhat, M. Periodontal Health Among Pregnant Women in Sri Lanka: A Cross-Sectional Study. Public Health Chall. 2024, 3, e209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhivya, S.; Preethi, J.; Sridharan, R. Oral Health Knowledge of Pregnant Women on Pregnancy Gingivitis and Children’s Oral Health. Int. J. Contemp. Dent. Res. 2023, 1, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bokhari, S.A.H.; Sanikommu, S.; BuHulayqah, A.; Al-Momen, H.; Al-Zuriq, A.; Khurshid, Z. Oral Health Awareness and Oral Hygiene Practices among Married Women of Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia. Eur. J. Gen. Dent. 2024, 13, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, I.D. Correlation of Dental Anxiety, Dental Phobia, and Psychological Constructs in a Sample of Patients Receiving Dental Care at Temple University Kornberg School of Dentistry. Doctoral Dissertation, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, N.A.B.; Haque, A. Pregnancy-related dental problems: A review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadhav, D.D.; Shelke, A.U.; Patil, K.; Tandel, S.P.; Dodal, A.A. Awareness of the Interrelationship of Periodontal Disease & Systematic Health: A Questionnaire-Based Survey. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2023, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Buset, S.L.; Walter, C.; Friedmann, A.; Weiger, R.; Borgnakke, W.S.; Zitzmann, N.U. Are periodontal diseases really silent? A systematic review of their effect on quality of life. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2016, 43, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcao, A.; Bullón, P. A review of the influence of periodontal treatment in systemic diseases. Periodontology 2000 2019, 79, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushehab, N.M.E.; Sreedharan, J.; Reddy, S.; D’Souza, J.; Abdelmagyd, H. Oral Hygiene Practices and Awareness of Pregnant Women about the Effects of Periodontal Disease on Pregnancy Outcomes. Int. J. Dent. 2022, 2022, 5195278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.; Baral, G.; Shrestha, R. Assessment of the Knowledge of the Association between Periodontal Status and Pregnancy Outcome among Obstetricians and Gynecologists. J. Nepal Health Res. Counc. 2022, 20, 534–538. [Google Scholar]

- Asa’ad, F.A.; Rahman, G.; Al Mahmoud, N.; Al Shamasi, E.; Al Khuwaileidi, A. Periodontal disease awareness among pregnant women in the central and eastern regions of Saudi Arabia. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2015, 6, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Crop. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows 2017; Version 25.0. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/us-en (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Alrumayh, A.; Alfuhaid, F.; Sayed, A.J.; Tareen, S.U.K.; Alrumayh, I.; Habibullah, M.A. Maternal Periodontal Disease: A Possible Risk Factor for Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in the Qassim Region of Saudi Arabia. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2021, 13 (Suppl. 2), S1723–S1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Albuquerque, O.M.; Abegg, C.; Rodrigues, C.S. Pregnant women’s perceptions of the Family Health Program concerning barriers to dental care in Pernambuco, Brazil. Cad. Saúde Pública 2004, 20, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rocha, J.S.; Arima, L.; Chibinski, A.C.; Werneck, R.I.; Moysés, S.J.; Baldani, M.H. Barriers and facilitators to dental care during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Cad. Saude Publica 2018, 34, e00130817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Codato, L.A.; Nakama, L.; Cordoni, L., Jr.; Higasi, M.S. Dental treatment of pregnant women: The role of healthcare professionals. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2011, 16, 2297–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Togoo, R.A.; Al-Almai, B.; Al-Hamdi, F.; Huaylah, S.H.; Althobati, M.; Alqarni, S. Knowledge of pregnant women about pregnancy gingivitis and children oral health. Eur. J. Dent. 2019, 13, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penmetsa, G.S.; Meghana, K.; Bhavana, P.; Venkatalakshmi, M.; Bypalli, V.; Lakshmi, B. Awareness, attitude and knowledge regarding oral health among pregnant women: A comparative study. Niger. Med. J. 2018, 59, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjan, P.; Pattanshetti, J.I.; Padmini, C.; Nagathan, V.M.; Sajjanar, M.; Siddiqui, T. Oral health related awareness and practices among pregnant women in Bagalkot District, Karnataka, India. J. Int. Oral Health JIOH 2015, 7, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Subedi, K.; Shrestha, A.; Bhagat, T. Oral health status and barriers to utilization of dental services among pregnant women in Sunsari, Nepal: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2024, 22, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalabadi, Y.M.; Campbell, M.K.; Gratton, R.; Jessani, A. Oral health status and dental services utilisation among a vulnerable sample of pregnant women. Int. Dent. J. 2024, in press. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Reshmi, R. Availability of public health facilities and utilization of maternal and child health services in districts of India. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2022, 15, 101070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Raeesi, S.; Al Matrooshi, K.; Khamis, A.H.; Tawfik, A.R.; Bain, C.; Jamal, M.; Atieh, M.; Shah, M. Awareness of Periodontal Health among Pregnant Females in Government Setting in United Arab Emirates. Eur. J. Dent. 2023, 17, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offenbacher, S.; Lieff, S.; Boggess, K.; Murtha, A.; Madianos, P.; Champagne, C.; McKaig, R.; Jared, H.; Mauriello, S.; Auten Jr, R. Maternal periodontitis and prematurity. Part I: Obstetric outcome of prematurity and growth restriction. Ann. Periodontol. 2001, 6, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaradoss, J.K.; Geevarghese, A.; Al Dosari, A.A. Causes of adverse pregnancy outcomes and the role of maternal periodontal status—A review of the literature. Open Dent. J. 2012, 6, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zi, M.Y.H.; Longo, P.L.; Bueno-Silva, B.; Mayer, M.P.A. Mechanisms involved in the association between periodontitis and complications in pregnancy. Front. Public Health 2015, 2, 117179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottrell-Carson, D. Promoting oral health to reduce adverse pregnancy outcomes. Birth 2004, 31, 66–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boggess, K.A.; Edelstein, B.L. Oral health in women during preconception and pregnancy: Implications for birth outcomes and infant oral health. Matern. Child Health J. 2006, 10, S169–S174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaszyńska, E.; Klepacz-Szewczyk, J.; Trafalska, E.; Garus-Pakowska, A.; Szatko, F. Dental awareness and oral health of pregnant women in Poland. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2015, 28, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reshmi, S. Oral health awareness among pregnant women in Neyyattinkara, Kerala-A cross sectional study. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. IOSR 2017, 16, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Costantinides, F.; Vettori, E.; Conte, M.; Tonni, I.; Nicolin, V.; Ricci, G.; Di Lenarda, R. Pregnancy, oral health and dental education: An overview on the northeast of Italy. J. Perinat. Med. 2020, 48, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambhir, R.S.; Nirola, A.; Gupta, T.; Sekhon, T.S.; Anand, S. Oral health knowledge and awareness among pregnant women in India: A systematic review. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2015, 19, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashiru, B.O.; Anthony, I.N. Oral health awareness and experience among pregnant women in a Nigerian tertiary health institution. J. Dent. Res. Rev. 2014, 1, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Frequency | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Educational level | University or master’s degree | 90 | (28.8) |

| Secondary | 56 | (17.9) | |

| Diploma | 165 | (52.9) | |

| Primary or less | 1 | (0.3) | |

| Total | 312 | (100) | |

| Age | Equal or less than 25 years | 25 | (8.0) |

| 26–30 years | 77 | (24.7) | |

| 31–35 years | 101 | (32.4) | |

| More than 35 years | 109 | (34.9) | |

| Total | 312 | (100) | |

| Number of pregnancies | Multigravida | 217 | (69.6) |

| Primigravida | 95 | (30.4) | |

| Total | 312 | (100) |

| Questions | Answers | ≤25 Years | 26–30 Years | 31–35 Years | >35 Years | Total | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| What is plaque? | a. Correct (soft deposit) | 9 (36) | 24 (31.2) | 33 (32.7) | 36 (33) | 102 (32.7) | 0.223 |

| b. Incorrect (hard deposition on teeth, I do not know, staining) | 16 (64) | 53 (68.8) | 68 (67.3) | 73 (67) | 210 (67.3) | ||

| What can plaque cause? | a. Correct (gum disease) | 8 (32) | 23 (29.9) | 26 (25.7) | 23 (21.1) | 80 (25.6) | 0.132 |

| b. Incorrect (discoloration, malformation, I do not know) | 17 (68) | 54 (70.1) | 75 (74.3) | 86 (78.9) | 232 (74.4) | ||

| What does bleeding gum indicate? | a. Correct (gum inflammation) | 21 (84) | 67 (87) | 85 (84.2) | 93 (85.3) | 266 (85.3) | 0.188 |

| b. Incorrect ( I do not know, healthy gum) | 4 (16) | 10 (13) | 16 (15.8) | 16 (14.7) | 46 (14.7) | ||

| How can you prevent gum disease? | a. Correct (brushing and flossing) | 22 (88) | 71 (92) | 85 (84) | 94 (86) | 272 (87.2) | 0.233 |

| b. Incorrect (taking vitamin C, I don’t know, soft diet) | 3 (12) | 6 (8) | 16 (16) | 15 (14) | 40 (12.8) |

| Questions | Answers | University or Master’s | Secondary | Diploma | Primary or Less | Total | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| What is plaque? | a. Correct (soft deposit) | 35 (38.9) | 11 (19.6) | 56 (34) | 0 (0) | 102 (32.7) | 0.043 * |

| b. Incorrect (hard deposition on teeth, I do not know, staining) | 55 (61.1) | 45 (80.4) | 109 (66) | 1 (100) | 210 (67.3) | ||

| What can plaque cause? | a. Correct (gum disease) | 31 (34.4) | 5 (8.9) | 44 (28.2) | 0 (0) | 80 (25.6) | 0.002 * |

| b. Incorrect (discoloration, malformation, I do not know) | 59 (65.6) | 51 (91.1) | 112 (71.8) | 1 (100) | 232 (74.4) | ||

| What does bleeding gum indicate? | a. Correct (gum inflammation) | 81 (90) | 43 (76.8) | 141 (85.5) | 1 (100) | 266 (85.3) | 0.035 * |

| b. Incorrect (I do not know, healthy gum) | 9 (10) | 13 (23.2) | 24 (14.5) | 0 (0) | 46 (14.7) | ||

| How can you prevent gum disease? | a. Correct (brushing and flossing) | 86 (95.6) | 38 (67.9) | 148 (89.7) | 0 (0) | 272 (87.2) | 0.000 * |

| b. Incorrect (taking vitamin C, I don’t know, soft diet) | 4 (4.4) | 18 (32.1) | 17 (10.3) | 1 (100) | 40 (12.8) |

| Questions | Answers | First Trimester | Second Trimester | Third Trimester | Total | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| What is plaque? | a. Correct (soft deposit) | 23 (37.1) | 36 (41.9) | 43 (26.2) | 102 (32.7) | 0.077 |

| b. Incorrect (hard deposition on teeth, I do not know, staining) | 39 (62.9) | 50 (58.1) | 121 (73.8) | 210 (67.3) | ||

| What can plaque cause? | a. Correct (gum disease) | 17 (27.4) | 30 (34.9) | 33 (20.1) | 80 (25.6) | 0.008 * |

| b. Incorrect (discoloration, malformation, I do not know) | 45 (72.6) | 56 (65.1) | 131 (79.9) | 232 (74.4) | ||

| What does bleeding gum indicate? | a. Correct (gum inflammation) | 51 (82.3) | 73 (84.8) | 142 (86.6) | 266 (85.3) | 0.067 |

| b. Incorrect (I do not know, healthy gum) | 11 (17.7) | 13 (15.1) | 22 (13.4) | 46 (14.7) | ||

| How can you prevent gum disease? | a. Correct (brushing and flossing) | 55 (88.7) | 76 (88.4) | 141 (86) | 272 (87.2) | 0.119 |

| b. Incorrect (taking vitamin C, I don’t know, soft diet) | 7 (11.3) | 10 (11.6) | 23 (14) | 40 (12.8) |

| Questions | Answers | Frequency | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| What causes gum inflammation in pregnant women? | a. Neglecting brushing | 83 | (26.6) |

| b. Dental plaque | 55 | (17.6) | |

| c. Hormonal changes | 19 | (6.1) | |

| d. I do not know | 141 | (45.2) | |

| e. Plaque and neglecting | 14 | (4.5) | |

| Total | 312 | (100.0) | |

| Do you think tooth brushing should be increased during pregnancy? | a. Yes | 240 | (76.9) |

| b. No | 35 | (11.2) | |

| c. I do not know | 37 | (11.9) | |

| Total | 312 | (100.0) | |

| Do you think that gum disease would lead to the delivery of a preterm or low-birth-weight infant? | a. Yes | 92 | (29.5) |

| b. No | 163 | (52.2) | |

| c. I do not know | 57 | (18.3) | |

| Total | 312 | (100.0) | |

| Do you think that smoking has a negative effect on the pregnant woman and her child? | a. Yes | 303 | (97.1) |

| b. No | 7 | (2.2) | |

| c. I do not know | 2 | (0.6) | |

| Total | 312 | (100.0) |

| Variables | p-Value | AOR (95% Cl) | p-Value | COR (95% Cl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education level | ||||

| Secondary or primary | 0.002 * | 3.1.36 (1.885–7.364) | 0.002 * | 3.047 (1.527–6.081) |

| Diploma | 0.539 | 0.842 (0.486–1.458) | 0.477 | 0.842 (0.482–1.406) |

| University level (Ref.) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Age | ||||

| Less than or equal to 25 years | 0.949 | 1.033 (0.383–2.782) | 0.595 | 0.787 (0.325–1.905) |

| 26–30 years | 0.705 | 0.881(0.456–1.700) | 0.196 | 0.674 (0.371–1.226) |

| 31–35 years | 0.102 | 0.606 (0.332–1.105) | 0.227 | 0.712 (0.410–1.235) |

| More than 35 years (Ref.) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Number of pregnancies | ||||

| Primigravida | 0.237 | 0.700 (0.387–1.265) | 0.112 | 0.665 (402–1.099) |

| Multigravida (Ref.) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Stage of pregnancy | ||||

| First trimester | 0.703 | 0.884 (0.470–1.665) | 0.304 | 0.731 (0.403–1.327) |

| Second trimester | 0.069 | 0.586 (0.330–1.043) | 0.015 * | 0.502 (0.289–0.872) |

| Third trimester (Ref.) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alkhurayji, K.S.; Althumairi, A.; Alsuhaimi, A.; Aldakhil, S.; Alshalawi, A.; Alzamil, M.; Asa’ad, F. Pregnant Women’s Awareness of Periodontal Disease Effects: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Study in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2413. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232413

Alkhurayji KS, Althumairi A, Alsuhaimi A, Aldakhil S, Alshalawi A, Alzamil M, Asa’ad F. Pregnant Women’s Awareness of Periodontal Disease Effects: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Study in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare. 2024; 12(23):2413. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232413

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlkhurayji, Khalid Saad, Arwa Althumairi, Abdulmunim Alsuhaimi, Sultan Aldakhil, Abdulrahman Alshalawi, Muath Alzamil, and Farah Asa’ad. 2024. "Pregnant Women’s Awareness of Periodontal Disease Effects: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Study in Saudi Arabia" Healthcare 12, no. 23: 2413. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232413

APA StyleAlkhurayji, K. S., Althumairi, A., Alsuhaimi, A., Aldakhil, S., Alshalawi, A., Alzamil, M., & Asa’ad, F. (2024). Pregnant Women’s Awareness of Periodontal Disease Effects: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Study in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare, 12(23), 2413. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232413