Now or Later? The Role of Neoadjuvant Treatment in Advanced Endometrial Cancer: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

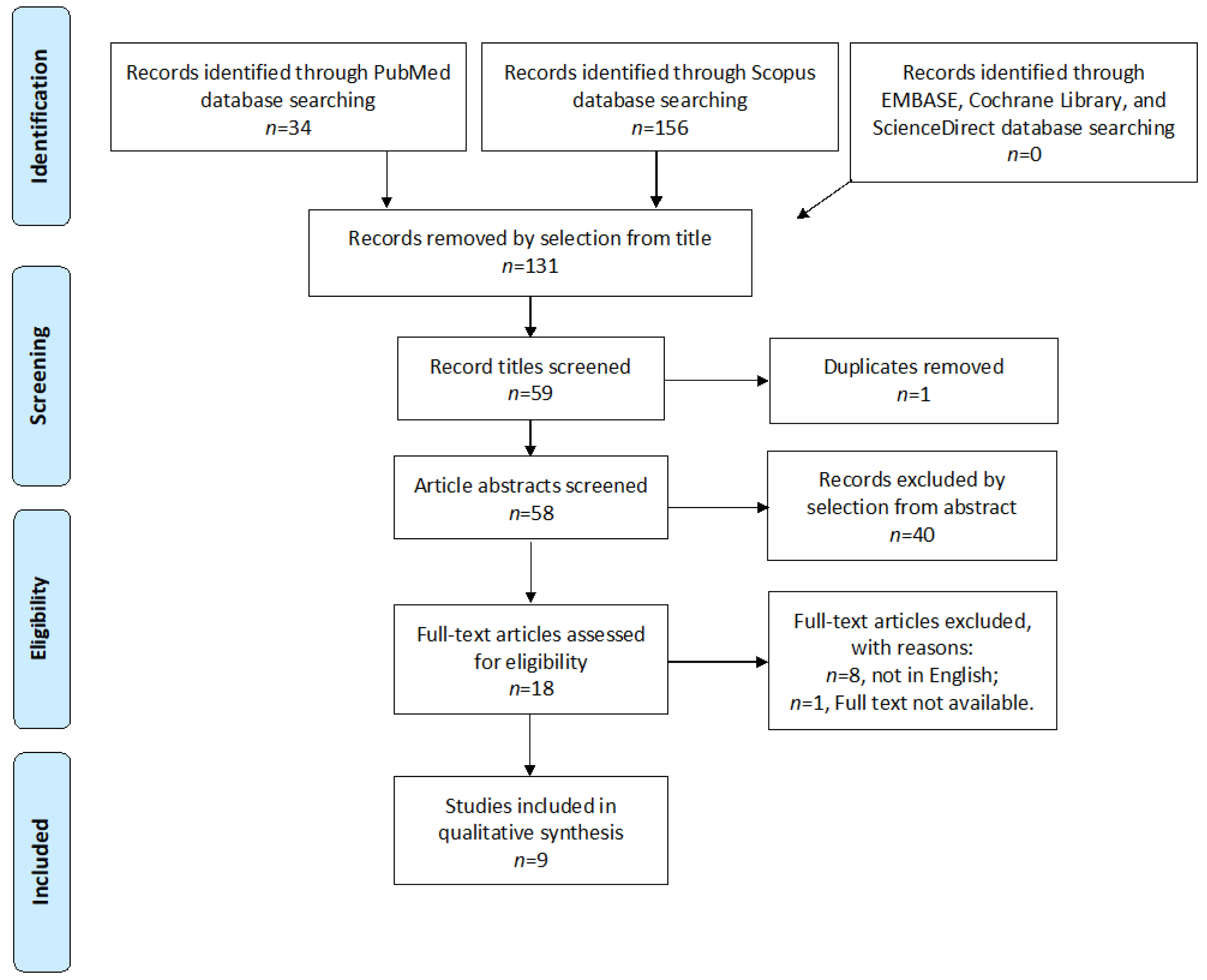

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Method

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Studies

3.2. Outcomes

3.3. Type of Surgery

3.4. Type of Neoadjuvant Treatment

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Main Results

4.2. Results in the Context of Published Literature

4.3. Implications for Practice and Future Research

4.4. Strength and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author, Year of Publication | Country | Selection | Comparability | Exposure | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bristow 2000 [15] | USA | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Vargo 2014 [18] | USA | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Alagkiozidis 2015 [19] | USA | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Zhu 2016 [20] | China | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Conway 2019 [21] | Canada | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Iheagwara 2019 [22] | USA | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Rauh 2020 [23] | USA | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Sakai 2022 [24] | Japan | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Mevius 2023 [25] | Germany | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

References

- Oaknin, A.; Bosse, T.; Creutzberg, C.; Giornelli, G.; Harter, P.; Joly, F.; Lorusso, D.; Marth, C.; Makker, V.; Mirza, M.; et al. Endometrial cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 860–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, N.; Creutzberg, C.; Amant, F.; Bosse, T.; González-Martín, A.; Ledermann, J.; Marth, C.; Nout, R.; Querleu, D.; Mirza, M.R.; et al. ESMO-ESGO-ESTRO Consensus Conference on Endometrial Cancer: Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-up. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2016, 26, 2–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pergialiotis, V.; Haidopoulos, D.; Christodoulou, T.; Rodolakis, I.; Prokopakis, I.; Liontos, M.; Rodolakis, A.; Thomakos, N. Factors That Affect Survival Outcomes in Patients with Endometrial Clear Cell Carcinoma. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touboul, E.; Belkacémi, Y.; Buffat, L.; Deniaud-Alexandre, E.; Lefranc, J.-P.; Lhuillier, P.; Uzan, S.; Jannet, D.; Uzan, M.; Antoine, M.; et al. Adenocarcinoma of the endometrium treated with combined irradiation and surgery: Study of 437 patients. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2001, 50, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, J.; Lee, K.-B.; Sung, K.; Kim, Y.B.; Kim, Y.S. Choosing the right adjuvant therapy for stage III–IVA endometrial cancer: A comparative analysis of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy. Gynecol. Oncol. 2024, 182, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, J.; Hoskin, P. Adjuvant Therapy for High-risk Endometrial Carcinoma. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 33, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuku, S.; Williams, M.; McCormack, M. Adjuvant therapy in stage III endometrial cancer: Treatment outcomes and survival. a single-institution retrospective study. Gynecol. Cancer 2013, 23, 1056–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boothe, D.; Orton, A.; Kim, J.; Poppe, M.M.; Werner, T.L.; Gaffney, D.K. Does Early Chemotherapy Improve Survival in Advanced Endometrial Cancer? Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 42, 813–817, Erratum in Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 43, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson-Ryan, I.; Binder, P.; Pourabolghasem, S.; Al-Hammadi, N.; Fuh, K.; Hagemann, A.; Thaker, P.; Schwarz, J.; Grigsby, P.; Mutch, D.; et al. Concomitant chemotherapy and radiation for the treatment of advanced-stage endometrial cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 134, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnadurai, A.; Breadner, D.; Baloush, Z.; Lohmann, A.E.; Black, M.; D’souza, D.; Welch, S. Adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel with “sandwich” method radiotherapy for stage III or IV endometrial cancer: Long-term follow-up at a single-institution. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2024, 35, e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spirtos, N.M.; Enserro, D.; Homesley, H.D.; Gibbons, S.K.; Cella, D.; Morris, R.T.; DeGeest, K.; Lee, R.B.; Miller, D.S. The addition of paclitaxel to doxorubicin and cisplatin and volume-directed radiation does not improve overall survival (OS) or long-term recurrence-free survival (RFS) in advanced endometrial cancer (EC): A randomized phase III NRG/Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 154, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yano, M.; Aso, S.; Sato, M.; Aoyagi, Y.; Matsumoto, H.; Nasu, K. Pembrolizumab and Radiotherapy for Platinum-refractory Recurrent Uterine Carcinosarcoma With an Abscopal Effect: A Case Report. Anticancer Res. 2020, 40, 4131–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kansagara, D.; O’Neil, M.; Nugent, S.; Freeman, M.; Low, A.; Kondo, K.; Elven, C.; Zakher, B.; Motu’apuaka, M.; Paynter, R.; et al. Benefits and Harms of Cannabis in Chronic Pain or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review; Department of Veterans Affairs: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- Bristow, R.E.; Zerbe, M.J.; Rosenshein, N.B.; Grumbine, F.C.; Montz, F. Stage IVB endometrial carcinoma: The role of cytoreductive surgery and determinants of survival. Gynecol. Oncol. 2000, 78, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargo, J.A.; Boisen, M.M.; Comerci, J.T.; Kim, H.; Houser, C.J.; Sukumvanich, P.; Olawaiye, A.B.; Kelley, J.L.; Edwards, R.P.; Huang, M.; et al. Neoadjuvant radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy followed by extrafascial hysterectomy for locally advanced endometrial cancer clinically extending to the cervix or parametria. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 135, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagkiozidis, I.; Grossman, A.; Tang, N.Z.; Weedon, J.; Mize, B.; Salame, G.; Lee, Y.-C.; Abulafia, O. Survival impact of cytoreduction to microscopic disease for advanced stage cancer of the uterine corpus: A retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 2015, 14, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wen, H.; Bi, R.; Wu, X. Clinicopathological characteristics, treatment and outcomes in uterine carcinosarcoma and grade 3 endometrial cancer patients: A comparative study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 27, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, J.L.; Lukovic, J.; Ferguson, S.E.; Zhang, J.; Xu, W.; Dhani, N.; Croke, J.; Fyles, A.; Milosevic, M.; Rink, A.; et al. Clinical Outcomes of Surgically Unresectable Endometrial Cancers. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 42, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheagwara, U.K.; Vargo, J.A.; Chen, K.S.; Burton, D.R.; Taylor, S.E.; Berger, J.L.; Boisen, M.M.; Comerci, J.T.; Orr, B.C.; Sukumvanich, P.; et al. Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation Therapy Followed by Extrafascial Hysterectomy in Locally Advanced Type II Endometrial Cancer Clinically Extending to Cervix. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2019, 9, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauh, L.; Staples, J.N.; Duska, L.R. Chemotherapy alone may have equivalent survival as compared to suboptimal surgery in advanced endometrial cancer patients. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 32, 100535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, K.; Yamagami, W.; Machida, H.; Ebina, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Tabata, T.; Kaneuchi, M.; Nagase, S.; Enomoto, T.; Aoki, D.; et al. A retrospective study for investigating the outcomes of endometrial cancer treated with radiotherapy. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 156, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mevius, A.; Karl, F.; Wacker, M.; Welte, R.; Krenzer, S.; Link, T.; Maywald, U.; Wilke, T. Real-world treatment of German patients with recurrent and advanced endometrial cancer with a post-platinum treatment: A retrospective claims data analysis. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 1929–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Uterine Neo-Plasms Version 1 2015. Aug. 2014. Available online: www.nccn.org (accessed on 14 January 2024).

- Nag, S.; Erickson, B.; Parikh, S.; Gupta, N.; Varia, M.; Glasgow, G. The American Brachytherapy Society recommendations for high-dose-rate brachytherapy for carcinoma of the endometrium. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2000, 48, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concin, N.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Vergote, I.; Cibula, D.; Mirza, M.R.; Marnitz, S.; Ledermann, J.; Bosse, T.; Chargari, C.; Fagotti, A.; et al. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2021, 31, 12–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudry, D.; Bécourt, S.; Scambia, G.; Fagotti, A. Primary or Interval Debulking Surgery in Advanced Ovarian Cancer: A Personalized Decision-a Literature Review. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2022, 24, 1661–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrillo, M.; Zucchetti, M.; Cianci, S.; Morosi, L.; Ronsini, C.; Colombo, A.; D’Incalci, M.; Scambia, G.; Fagotti, A. Pharmacokinetics of cisplatin during open and minimally-invasive secondary cytoreductive surgery plus HIPEC in women with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer: A prospective study. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 30, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommoss, S.; McConechy, M.K.; Kommoss, F.; Leung, S.; Bunz, A.; Magrill, J.; Britton, H.; Grevenkamp, F.; Karnezis, A.; Yang, W.; et al. Final validation of the ProMisE molecular classifier for endometrial carcinoma in a large population-based case series. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 1180–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, E.; Becker, C.; Rogak, L.J.; Schrag, D.; Reeve, B.B.; Spears, P.; Smith, M.L.; Gounder, M.M.; Mahoney, M.R.; Schwartz, G.K.; et al. Composite grading algorithm for the National Cancer Institute’s Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). Clin. Trials 2021, 18, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, J.A.; Beriwal, S. Image-based brachytherapy for cervical cancer. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 5, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charra-Brunaud, C.; Harter, V.; Delannes, M.; Haie-Meder, C.; Quetin, P.; Kerr, C.; Castelain, B.; Thomas, L.; Peiffert, D. Impact of 3D image-based PDR brachytherapy on outcome of patients treated for cervix carcinoma in France: Results of the French STIC prospective study. Radiother. Oncol. 2012, 103, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, M.E.; Filiaci, V.L.; Muss, H.; Spirtos, N.M.; Mannel, R.S.; Fowler, J.; Thigpen, J.T.; Benda, J.A. Randomized phase III trial of whole-abdominal irradiation versus doxorubicin and cisplatin chemotherapy in advanced endometrial carcinoma: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haie-Meder, C.; Mazeron, R.; Magné, N. Clinical evidence on PET-CT for radiation therapy planning in cervix and endometrial cancers. Radiother. Oncol. 2010, 96, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronsini, C.; Iavarone, I.; Reino, A.; Vastarella, M.G.; De Franciscis, P.; Sangiovanni, A.; Della Corte, L. Radiotherapy and Chemotherapy Features in the Treatment for Locoregional Recurrence of Endometrial Cancer: A Systematic Review. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RAINBO Research Consortium. Refining adjuvant treatment in endometrial cancer based on molecular features: The RAINBO clinical trial program. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2022, 33, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.R.; Chase, D.M.; Slomovitz, B.M.; Christensen, R.D.; Novák, Z.; Black, D.; Gilbert, L.; Sharma, S.; Valabrega, G.; Landrum, L.M.; et al. Dostarlimab for Primary Advanced or Recurrent Endometrial Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 2145–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year of Publication | Country | Period of Enrollment | Study Design | FIGO Stage | Endometrioid Cancer (%) | RT 0 (%) | No. of Participants | Treatment | Median FU Period (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bristow 2000 [15] | USA | 1990–1998 | Retrospective Monocenter Cohort | IVB | 33.8 | 55.4 | 65 | Upfront Surgery | 14.7 |

| Vargo 2014 [16] | USA | 1999–2014 | Retrospective Monocenter Cohort | IIIB–IV | 83 | NR | 36 | Neoadjuvant EBRT ± CT | 20 |

| Alagkiozidis 2015 [17] | USA | 1984–2009 | Retrospective Monocenter Cohort | III–IV | 60 | 64 | 168 | Upfront Surgery | 18 |

| Zhu 2016 [18] | China | 2006–2013 | Retrospective Monocenter Cohort | III–IV | NR | NR | 42 | Upfront Surgery | 49.2 |

| Conway 2019 [19] | Canada | 2000–2018 | Retrospective Monocenter Cohort | II–IVA | 59 | NR | 59 | Neoadjuvant CT/RT | 26 |

| Iheagwara 2019 [20] | USA | 2008–2018 | Retrospective Monocenter Cohort | II–IV | NR | 94 | 34 | Neoadjuvant CT | 60 |

| Rauh 2020 [21] | USA | 2000–2015 | Retrospective Multicenter Cohort | III–IV | 38.6 | 31 | 96 | Neoadjuvant CT | 24.4 |

| Sakai 2022 [22] | Japan | 2004–2011 | Retrospective Multicenter Cohort | I–IV | NR | 73.5 | 177 | Neoadjuvant EBRT/BT | N/A |

| Mevius 2023 [23] | Germany | 2010–2020 | Retrospective Multicenter Cohort | III–IV | NR | NR | 201 | Neoadjuvant CT | 12 |

| Author, Year of Publication | Treatment | 5-Year PFS (%) | 5-Year OS (%) | 5-Year RR (%) | National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events ≥ 3 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bristow 2000 [15] | Upfront surgery | 23.1 | 6.2 | N/A | N/A |

| Vargo 2014 [16] | Neoadjuvant EBRT ± CT | 73 | 100 | 27 | 9 |

| Alagkiozidis 2015 [17] | Upfront surgery | N/A | 26 | N/A | N/A |

| Zhu 2016 [18] | Upfront surgery | N/A | 49.7 | N/A | N/A |

| Conway 2019 [19] | Neoadjuvant CT/RT | 42 | 70 | 58 | 19 |

| Iheagwara 2019 [20] | Neoadjuvant CT | 52.5 | 63.7 | 47.5 | N/A |

| Rauh 2020 [21] | Neoadjuvant CT | N/A | 31.6 | 64.6 | N/A |

| Sakai 2022 [22] | Neoadjuvant EBRT/BT | N/A | 15.5 | N/A | 22 |

| Mevius 2023 [23] | Neoadjuvant CT | N/A | 33.2 | N/A | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ronsini, C.; Iavarone, I.; Carotenuto, A.; Raffone, A.; Andreoli, G.; Napolitano, S.; De Franciscis, P.; Ambrosio, D.; Cobellis, L. Now or Later? The Role of Neoadjuvant Treatment in Advanced Endometrial Cancer: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2404. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232404

Ronsini C, Iavarone I, Carotenuto A, Raffone A, Andreoli G, Napolitano S, De Franciscis P, Ambrosio D, Cobellis L. Now or Later? The Role of Neoadjuvant Treatment in Advanced Endometrial Cancer: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2024; 12(23):2404. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232404

Chicago/Turabian StyleRonsini, Carlo, Irene Iavarone, Alessandro Carotenuto, Antonio Raffone, Giada Andreoli, Stefania Napolitano, Pasquale De Franciscis, Domenico Ambrosio, and Luigi Cobellis. 2024. "Now or Later? The Role of Neoadjuvant Treatment in Advanced Endometrial Cancer: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 12, no. 23: 2404. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232404

APA StyleRonsini, C., Iavarone, I., Carotenuto, A., Raffone, A., Andreoli, G., Napolitano, S., De Franciscis, P., Ambrosio, D., & Cobellis, L. (2024). Now or Later? The Role of Neoadjuvant Treatment in Advanced Endometrial Cancer: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 12(23), 2404. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232404