Experience of Family Caregivers in Long-Term Care Hospitals During the Early Stages of COVID-19: A Phenomenological Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Selection of Study Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ensuring Rigor and Researcher Preparation

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: A Prison-like Long-Term Care Hospital Bound by Strict COVID-19 Prevention Rules

3.1.1. Difficult Visitation Processes and Limited Visiting Hours

“[The noncontact visitation] is only 10 min. Just 10 min. I can’t touch, and I was constantly watching the clock. After 10 min, I have to leave because others are waiting. So, even while looking at my mother, I feel anxious. I should ask more and see her face more. But my mother, she just cries for 10 min, and then it’s over. She cries…it’s very upsetting. Even after leaving, I feel uneasy”.(P8)

“I can’t visit in person, so all the visits are noncontact. And if I want to arrange a noncontact visit, I have to book it days in advance”.(P3)

3.1.2. Unable to Touch Parents and Blocked by a Glass Partition

“Now, since direct meetings between caregivers and patients aren’t allowed, all I can do is go and see [my mother], but it feels awkward. I really need to see and hold her hand after the meeting. But there’s this glass partition, and if not that, then we have to talk over the phone. It’s not a school or a prison. It feels more uncomfortable…. Honestly, it’s better not to see her at all. When I do, I feel uneasy for the rest of the day, and I can’t focus on work”.(P9)

“After a noncontact visit, the older adult often experiences emotional swings. Sometimes, I feel scared about visiting because I’m worried they won’t adapt”.(P3)

3.1.3. A Haven Amid COVID-19

“I believe the visitation guidelines are necessary. It’s very frustrating and hard, but that’s the only way to protect the patients in nursing homes and keep them healthy. It’s something we just have to accept”.(P1)

“There are so many vulnerable patients in the hospital, so we have to avoid infection. Normal people may not understand, but it’s the right thing to do for everyone’s safety”.(P9)

3.2. Theme 2: Growing Affection for Unreachable Parents

3.2.1. Having to Entrust Parents to Medical Staff and Caregivers Fully

“Before, I could go in and directly check on my mother’s care, which gave me peace of mind since I could see for myself. Now, I just talk to her through the glass, and I feel a bit anxious, not knowing how she’s really doing”.(P2)

“I don’t know what the caregivers are doing. I just have to trust them since I can’t go in and check for myself”.(P6)

3.2.2. The Fading Presence of Parents in Daily Life

“If I were seeing her, I’d feel emotions like guilt, but since I can’t, I’ve just become indifferent. Honestly, I think I’ve grown numb. Since I can’t see her, it’s like she’s gradually slipping away”.(P5)

3.2.3. Meaningless Screams in Confinement

“During the first year of the pandemic, my mom kept asking to go home, saying she wanted to be discharged and live at home again. She said it every day, and my brother and I took turns calling her, but it was so painful to hear”.(P6)

“When I heard that the nurses were confining the patients, even running over if the door opened, I felt guilty. I felt like I was putting my parents through unnecessary suffering by keeping them there”.(P3)

“Not being able to see us is the hardest part for them. They think we’re making excuses, that we’re lying about not being able to visit because of COVID. They start to distrust us…. It feels like my efforts aren’t being understood. When they say we’re using COVID as an excuse, it really hurts”.(P3)

3.3. Theme 3: Adapting to a New and Safer Daily Life

3.3.1. Strengthening Familial Bonds Despite Fewer Visits

“I can’t visit as often, so I feel even sorrier for her now”.(P2)

“I still regret not doing more for them when they were healthy, like buying supplements or taking them on a trip. I feel sorry about it all the time”.(P3)

“Since I can’t visit often, I worry about her more, and I feel more affectionate toward her”.(P1)

3.3.2. Creating and Anticipating New Routines

“We got my mom a smartphone for video calls, but the staff didn’t always have time to help, so I bought her a phone so we could stay in touch directly”.(P8)

“Just in case this goes on longer, I’ve already set up another phone for my mom so we can have video calls in the future”.(P3)

“My mom’s vaccinated, so I’m hoping things will loosen up, and maybe if the staff and patients all get their second doses, visitation rules will relax, too”.(P2)

“Once we’re all vaccinated, things will get better. We’ll be able to meet again, hold hands, and eat together. Things will improve soon”.(P4)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Song, Z.; Hu, Y.; Tao, Z.-W.; Tian, J.-H.; Pei, Y.-Y.; et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 2020, 579, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J. Concerns rise over summer COVID-19 wave. The Korea Herald, 12 August 2024. Available online: https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20240812000555 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Lee, E.H. COVID-19 generation, good health! Issue Diagn. 2020, 414, 1–21. Available online: https://www.gri.re.kr/web/contents/issdiag.do (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- UN News Global Perspective Human Stories. UN Leads Call to Protect Most Vulnerable from Mental Health Crisis During and After COVID-19. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/05/1063882 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Atlantak. ‘Corona blue’ one-third of Americans are depressed, anxious. Admin K-News USA, 26 April 2020. Available online: https://atlantak.com (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Lee, H.J.; Lee, H.Y. COVID-19 stress: Is the level of COVID-19 stress same for everybody?—Segmentation approach based on COVID-19 stress level. Korea Logist. Rev. 2020, 30, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksen, S.D.; Ringsberg, K.C. Living the situation stress-experiences among intensive care patients. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2007, 23, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.O. Exploring pain, life, and meaning of physical activity among dementia caregivers: A photovoice study. Korean J. Phys. Educ. 2017, 56, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Park, Y.W.; Kim, K.A.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, E.S.; Yun, H.Y.; Yoo, J.S. Stress, social supports, and coping among the family members of the patients in ICU. J. Korean Clin. Nurs. Res. 2007, 13, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). Impact of COVID-19 on Canada’s Health Care Systems; CIHI: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/covid-19-resources/impact-of-covid-19-on-canadas-health-care-systems (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- World Health Organization. Preventing and managing COVID-19 across long-term care services. Policy Brief, 24 July 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Policy_Brief-Long-term_Care-2020.1 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Chae, S.Y.; Kim, K.H. Physical symptoms, hope and family support of cancer patients in the general hospitals and long-term care hospitals. Korean J. Adult Nurs. 2013, 25, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, E.Y.; Kim, H.R. Family members’ experience in caring for elderly with dementia in long-term care hospitals. J. Korean Gerontol. Nurs. 2020, 22, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, G.; Rowland, C.; van den Berg, B.; Hanratty, B. Psychological morbidity and general health among family caregivers during end-of-life cancer care: A retrospective census survey. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 1605–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, A.F.; Vanessa, B.S.; Patricia, A.M.; Michelle, T.; Inez, A.; Jane, I. Caregiving at the end of life: Perceptions of health care quality and quality of life among patients and caregivers. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2006, 31, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristjanson, L.J.; Aoun, S. Palliative care for families: Remembering the hidden patients. Can. J. Psychiatr. 2004, 49, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, M.; Mikulincer, M.; Rydall, A.; Walsh, A.; Rodin, G. Hidden morbidity in cancer: Spouse caregivers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 4829–4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunfeld, E.; Coyle, D.; Whelan, T.; Clinch, J.; Reyno, L.; Earle, C.C.; Willan, A.; Viola, R.; Coristine, M.; Janz, T.; et al. Family caregiver burden: Results of a longitudinal study of breast cancer patients and their principal caregivers. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2004, 170, 1795–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, D.R.; Lee, G.Y. Experiences of nurses at a general hospital in Seoul which is temporarily closed due to COVID-19. J. Korean Acad. Soc. Nurs. Educ. 2020, 26, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B. Experience of COVID-19 patients care in infectious diseases specialized hospital in Daegu. J. Mil. Nurs. Res. 2020, 38, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi, A.E. Burnout in nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: The rising need for development of evidence-based risk assessment and supportive interventions. Evid.-Based Nurs. 2021, 25, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaizzi, P.F. Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. In Existential-Phenomenological Alternatives for Psychology; Valle, R.S., Kings, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1978; pp. 48–71. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, M. Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Forum Qual. Sozialforschung/Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2010, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Han, S.J. Effects of social support for elderly residents’ primary caregivers in long-term care facilities on caregivers’ positive feelings and burden. J. Korean Acad. Soc. Home Care Nurs. 2019, 26, 199–209. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, S.H. An analysis of the difference between importance and satisfaction of selection attributes and reuse intention in long-term care hospital for elderly patient caregivers. Korean J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 20, 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, T.Y.M.; Lim, W.K. A study on the relationship among the patient caregiver’s consumption value and hospital satisfaction, psychological well-being in geriatric hospitals. J. Dig. Converg. 2014, 12, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Fourth Generation Evaluation; SAGE: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). A timeline of South Korea’s response to COVID-19. CSIS, 27 March 2020. Available online: https://www.csis.org/analysis/timeline-south-koreas-response-covid-19 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Lee, M.J.; Byun, S.H. The effects of a video call on the facility satisfaction of the elderly in the long-term facilities banned from visiting due to COVID-19. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2021, 12, 2431–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Given, B.A.; Given, C.W. Family caregiving for the elderly. Ann. Rev. Nurs. Res. 1991, 9, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, S.H.; Choi, S.Y. Changes in caregiving burden of families after using long-term care services. J. Crit. Soc. Welf. 2013, 40, 7–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y.M. A study on the lived experience of baby boomers who bereaved their parents in long-term care facilities. Stud. Life Cult. 2021, 61, 73–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW). Improving Visiting Standards for Nursing Hospitals and Nursing Facilities, Actively Implementing Non-Contact Visits and Implementing Limited Contact Visits; MOHW. 2021. Available online: https://www.mohw.go.kr/synap/doc.html?fn=1614910576202_20210305111616.hwp&rs=/upload/result/202408/ (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- World Health Organization. Social Isolation and Loneliness Among Older People: Advocacy Brief; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030749 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Yang, Y.J. Qualitative meta-synthesis on life experiences of the elderly in care homes. Korean Assoc. Qual. Inq. 2020, 6, 193–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Cipolletta, S.; Gammino, G.; Palmieri, M. Caring for a person with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study with family caregivers. Ageing Soc. 2021, 41, 1948–1965. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, A.; Field, D.; Wee, B. The impact of psychosocial interventions on informal caregivers of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0249075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfilippo, F.; La Via, L.; Schembari, G.; Tornitore, F.; Zuccaro, G.; Morgana, A.; Valenti, M.R.; Oliveri, F.; Pappalardo, F.; Astuto, M.; et al. Implementation of video-calls between patients admitted to intensive care unit during the COVID-19 pandemic and their families: A pilot study of psychological effects. J. Anesth. Analg. Crit. Care 2022, 2, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J. Understanding family caregivers’ experiences of living with dementia: A transcendental phenomenological inquiry. Korea Gerontol. Soc. 2007, 27, 963–986. [Google Scholar]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Caregivers of patients admitted to long-term care hospitals for at least six months at the time of the interview. | Non-immediate family caregivers |

| Only immediate family members of the patient were eligible to participate. | Caregivers of patients admitted to long-term care hospitals for less than six months were excluded. |

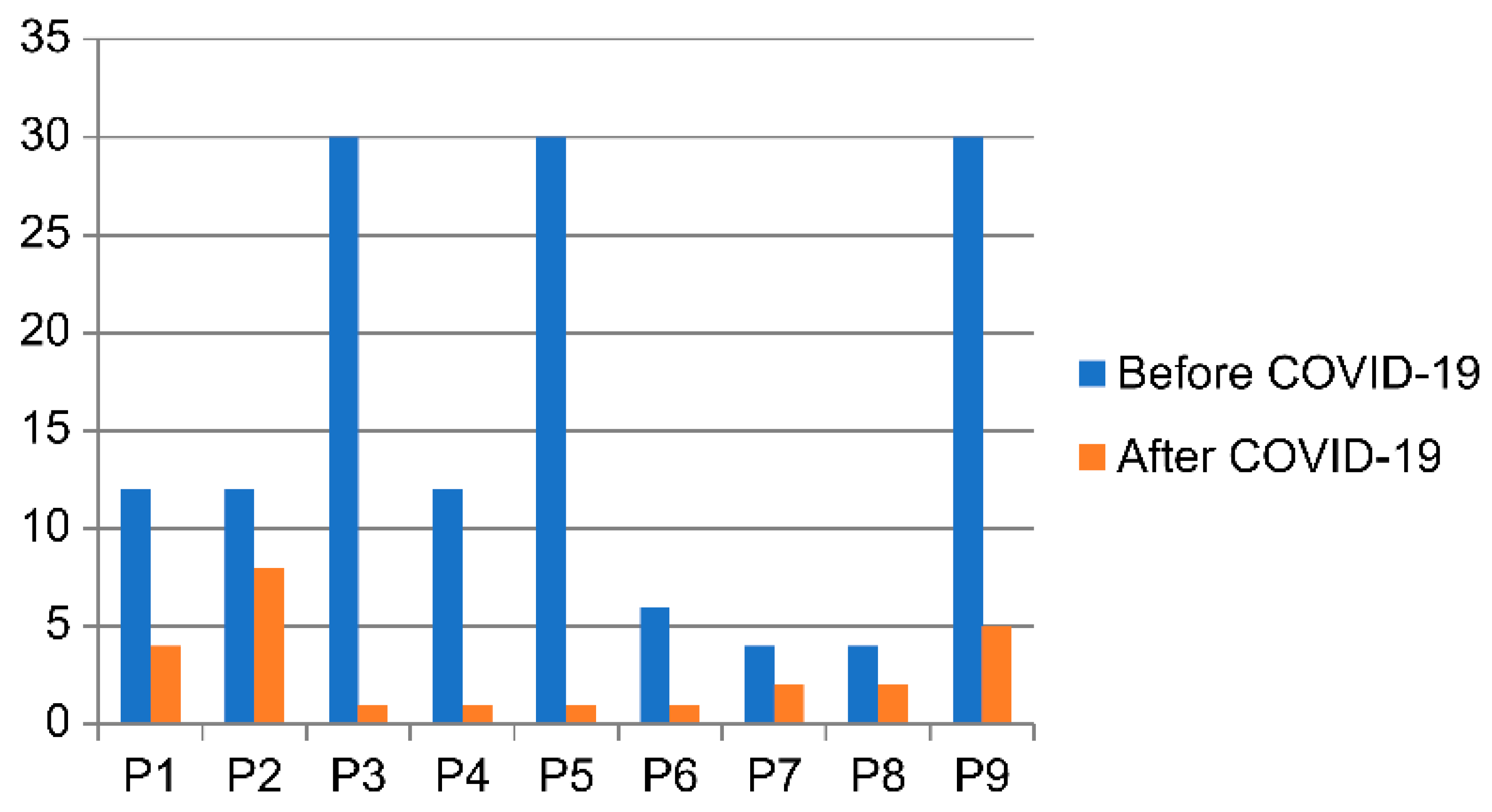

| Characteristics of Participants (Caregiver) | Characteristics of Patients | Number of Meetings | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Per Month) | |||||||||

| No | Sex | Age | Education | Occupation | Relationship | Sex | Hospitalization | Before | After |

| Period | COVID-19 | COVID-19 | |||||||

| (Year) | |||||||||

| 1 | Female | 51 | Bachelor’s | Employee | Daughter | Female | 12 | 12 | 4 |

| 2 | Female | 48 | Bachelor’s | Homemaker | Daughter | Female | 2 | 12 | 8 |

| 3 | Female | 54 | High-school | Homemaker | Daughter | Male | 6 | 30 | 1 |

| Female | |||||||||

| 4 | Female | 62 | High-school | Employee | Daughter-in-law | Female | 7 | 12 | 1 |

| 5 | Male | 55 | Bachelor’s | Employee | Son | Female | 5 | 30 | 1 |

| 6 | Female | 62 | High-school | Homemaker | Daughter | Female | 9 | 6 | 1 |

| 7 | Female | 53 | High-school | Homemaker | Daughter | Female | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| 8 | Female | 54 | Bachelor’s | Homemaker | Daughter-in-law | Female | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| 9 | Male | 61 | High-school | Employee | Son | Female | 7 | 30 | 5 |

| Categories | Theme Clusters |

|---|---|

| Prison-like long-term care hospital bound by strict COVID-19 prevention rules | Difficult visitation processes and limited visiting hours |

| Unable to touch parents, blocked by a glass partition | |

| A safe haven amidst COVID-19 | |

| Growing affection for unreachable parents | Having to fully entrust parents to medical staff and caregivers |

| The fading presence of parents in daily life | |

| Meaningless screams in confinement | |

| Adapting to a new and safer daily life | Strengthening familial bonds despite fewer visits |

| Creating and anticipating new routines |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cha, H.-J.; Jeon, M.-K. Experience of Family Caregivers in Long-Term Care Hospitals During the Early Stages of COVID-19: A Phenomenological Analysis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2254. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12222254

Cha H-J, Jeon M-K. Experience of Family Caregivers in Long-Term Care Hospitals During the Early Stages of COVID-19: A Phenomenological Analysis. Healthcare. 2024; 12(22):2254. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12222254

Chicago/Turabian StyleCha, Hye-Ji, and Mi-Kyeong Jeon. 2024. "Experience of Family Caregivers in Long-Term Care Hospitals During the Early Stages of COVID-19: A Phenomenological Analysis" Healthcare 12, no. 22: 2254. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12222254

APA StyleCha, H.-J., & Jeon, M.-K. (2024). Experience of Family Caregivers in Long-Term Care Hospitals During the Early Stages of COVID-19: A Phenomenological Analysis. Healthcare, 12(22), 2254. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12222254