The Correlation Between Effort–Reward Imbalance at Work and the Risk of Burnout Among Nursing Staff Working in an Emergency Department—A Pilot Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How many emergency nursing staff members face an increased risk of effort–reward imbalance at work?

- How high is the risk of burnout among this occupational group?

- Is the risk of burnout correlated with effort–reward imbalance at work among emergency nurses?

- Which components of reward (esteem, job promotion, job security) are related to the risk of burnout?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Recruitment

2.2. Questionnaire

2.2.1. Effort–Reward Imbalance Questionnaire

2.2.2. Maslach Burnout Inventory

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethics

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

- Owing to the small sample size investigated in this pilot study, the results of this research cannot be generalized. It would be desirable to conduct studies in emergency departments throughout Germany, which should be designed to take into account the long-term effects. To increase the validity of this research, the sample size must be increased, and this study should continue at several locations and be verified by longitudinal studies.

- This study has only examined the correlation between ERI and burnout. The correlations were not verified through regression analyses controlling for various socio-demographic characteristics.

- This is a convenience sample, so it is not possible to draw conclusions about all emergency personnel.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Darius, S.; Balkaner, B.; Böckelmann, I. Psychische Beeinträchtigungen infolge erhöhter Belastungen bei Notärzten. Notf. Rettungsmed 2021, 24, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriaenssens, J.; de Gucht, V.; Maes, S. Determinants and prevalence of burnout in emergency nurses: A systematic review of 25 years of research. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohmert, W.; Raab, S. The stress-strain concept as an engineering approach serving the interdisciplinary work design. Int. J. Hum. Factors Manuf. 1995, 5, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberger, H.J. Staff Burn-Out. J. Soc. Issues 1974, 30, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. The conceptualization and measurement of burnout: Common ground and worlds apart: The views expressed in Work & Stress Commentaries are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily represent those of any other person or organization, or of the journal. Work Stress 2005, 19, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Beer, L.T.; van der Vaart, L.; Escaffi-Schwarz, M.; de Witte, H.; Schaufeli, W.B. Maslach Burnout Inventory—General Survey. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2024, 40, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, R.; Buyken, D. Der aktuelle Kenntnisstand über Erkrankungsrisiken durch psychische Arbeitsbelastungen. Z. Arb. Organisationspsychol. 2015, 59, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Killmer, C.H.; Siegrist, J.; Schaufeli, W.B. Effort-reward imbalance and burnout among nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 31, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jachens, L.; Houdmont, J.; Thomas, R. Effort-reward imbalance and burnout among humanitarian aid workers. Disasters 2019, 43, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joksimovic, L.; Starke, D.; Knesebeck, O.v.d.; Siegrist, J. Perceived work stress, overcommitment, and self-reported musculoskeletal pain: A cross-sectional investigation. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2002, 9, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuper, H.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Siegrist, J.; Marmot, M. When reciprocity fails: Effort-reward imbalance in relation to coronary heart disease and health functioning within the Whitehall II study. Occup. Environ. Med. 2002, 59, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peter, R.; Geißler, H.; Siegrist, J. Associations of effort-reward imbalance at work and reported symptoms in different groups of male and female public transport workers. Stress Med. 1998, 14, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugulies, R.; Aust, B.; Madsen, I.E. Effort-reward imbalance at work and risk of depressive disorders. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2017, 43, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theorell, T.; Hammarström, A.; Aronsson, G.; Träskman Bendz, L.; Grape, T.; Hogstedt, C.; Marteinsdottir, I.; Skoog, I.; Hall, C. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Zhou, X.; Yin, X.; Jiang, N.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lv, C.; Gong, Y. Effort-Reward Imbalance in Emergency Department Physicians: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 793619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, R.; Heaton, K.; Davis, M.; Chen, P.; Dickinson, D.A.; Lungu, C.T. A Cross Sectional Study Evaluating Psychosocial Job Stress and Health Risk in Emergency Department Nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Yang, H.; Yin, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Lv, C.; Mu, K.; Gong, Y. Evaluating effort-reward imbalance among nurses in emergency departments: A cross-sectional study in China. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuy, M.; Dutheil, F.; Alvarez, A.; Godet, T.; Adeyemi, O.J.; Clinchamps, M.; Schmidt, J.; Lambert, C.; Bouillon-Minois, J.-B. Influence of COVID-19 on Stress at Work During the First Wave of the Pandemic Among Emergency Health Care Workers. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2023, 17, e455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Tudela, Á.; Simonelli-Muñoz, A.J.; Gallego-Gómez, J.I.; Rivera-Caravaca, J.M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on stress and sleep in emergency room professionals. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 5037–5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistisches Bundesamt. Pressemittteilung Nr. 033 vom 24.01.2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2024/01/PD24_033_23_12.html (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- VERDI. Fachkräftemangel im Rettungsdienst? 2024. Available online: https://gesundheit-soziales-bildung.verdi.de/themen/fachkraeftemangel/++co++ad02b49e-58f1-11e8-b5f6-525400f67940 (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Siegrist, J.; Wege, N.; Pühlhofer, F.; Wahrendorf, M. A short generic measure of work stress in the era of globalization: Effort-reward imbalance. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2009, 82, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. Maslach Burnout Inventory—General Survey (MBI-GS). In MBI Manual, 3. Aufl; Maslach, C., Jackson, S.E., Leiter, M.P., Eds.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, 3. Aufl; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Büssing, A.; Perrar, K.-M. Die Messung von Burnout. Untersuchung einer deutschen Fassung des Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI-D). Diagnostica 1992, 38, 328–353. [Google Scholar]

- Kalimo, R.; Pahkin, K.; Mutanen, P.; Topipinen-Tanner, S. Staying well or burning out at work: Work characteristics and personal resources as long-term predictors. Work Stress 2003, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2. Aufl; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Dragano, N.; Siegrist, J.; Nyberg, S.T.; Lunau, T.; Fransson, E.I.; Alfredsson, L.; Bjorner, J.B.; Borritz, M.; Burr, H.; Erbel, R.; et al. Effort-Reward Imbalance at Work and Incident Coronary Heart Disease: A Multicohort Study of 90,164 Individuals. Epidemiology 2017, 28, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, A.; Zenger, M.; Brähler, E.; Spitzer, S.; Scheuch, K.; Seibt, R. Effort-Reward Imbalance and Mental Health Problems in 1074 German Teachers, Compared with Those in the General Population. Stress Health 2016, 32, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maske, U.E.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Seiffert, I.; Jacobi, F.; Hapke, U. Häufigkeit und psychiatrische Komorbiditäten von selbstberichtetem diagnostiziertem Burnout-Syndrom. Psychiatr. Praxi 2015, 43, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.-W.; Hu, F.-H.; Jia, Y.-J.; Tang, W.; Zhang, W.-Q.; Chen, H.-L. Global prevalence of nursing burnout syndrome and temporal trends for the last 10 years: A meta-analysis of 94 studies covering over 30 countries. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 5836–5854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; La Fuente-Solana EI de Albendín-García, L.; Vargas-Pecino, C.; Ortega-Campos, E.M.; La Cañadas-de Fuente, G.A. Prevalence of Burnout Syndrome in Emergency Nurses: A Meta-Analysis. Crit. Care Nurse 2017, 37, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darius, S.; Hohmann, C.B.; Siegel, L.; Böckelmann, I. Zusammenhang zwischen dem Burnout-Risiko und individuellen Stressverarbeitungsstrategien bei Kindergartenerzieherinnen. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2021, 71, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böckelmann, I.; Kirsch, M. Zufriedenheit mit den Arbeitsbedingungen und das Burnout-Risiko der Pädagogen an den Musikschulen: Ein Altersvergleich. Zbl Arbeitsmed 2023, 73, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, K.; Böckelmann, I.; Karlsen, H.R.; Lux, A.; Thielmann, B. Effort-Reward Imbalance, Mental Health and Burnout in Occupational Groups That Face Mental Stress. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 62, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakemam, E.; Chegini, Z.; Rouhi, A.; Ahmadi, F.; Majidi, S. Burnout and its relationship to self-reported quality of patient care and adverse events during COVID-19: A cross-sectional online survey among nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1974–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, V.; Hughes, V.; Wilson, D.R. Nursing Burnout and Its Impact on Health. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 57, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielmann, B.; Ifferth, M.; Böckelmann, I. Resilience as Safety Culture in German Emergency Medical Services: Examining Irritation and Burnout. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Nonrisk Group | Risk Group | Total Sample | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± Standard Deviation | ||||

| Age [Years] | 35.9 ± 12.05 | 34.3 ± 9.44 | 35.1 ± 10.7 | pt-Test = 0.673 |

| Years working in the CED | 6.3 ± 8.0 | 7.6 ± 7.6 | 7.0 ± 7.6 | pMann-Whitney = 0.301 |

| Number (%) | ||||

| Gender | 7 (36.8%) Men 12 (63.2%) Woman | 4 (25%) Men 12 (75%) Woman | 11 (31.4%) Men 24 (68.6%) Woman | pFisher = 0.493 |

| ERI Scales with Subscales | Nonrisk Group | Risk Group | Total Sample | pMann-Whitney |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± Standard Deviation [Points] Median (Min–Max) [95% Confidence Interval] | ||||

| Effort | 9.1 ± 2.33 | 12.1 ± 1.57 | 10.5 ± 2.49 | <0.001 |

| 9 (3–13) | 12 (9–14) | 11 (3–14) | ||

| [7.98–10.23] | [11.23–12.90] | [9.64–11.30] | ||

| Reward | 30.7 ± 3.38 | 21.2 ± 4.29 | 26.3 ± 6.10 | <0.001 |

| 31 (23–35) | 21 (13–28) | 27 (13–35) | ||

| [29.05–32.32] | [18.90–23.48] | [24.27–28.34] | ||

| Job promotion | 12.7 ± 2.16 | 7.9 ± 1.93 | 10.5 ± 3.17 | <0.001 |

| 13 (8–15) | 8 (5–13) | 10 (5–15) | ||

| [11.64–13.73] | [6.85–8.90] | [9.39–11.50] | ||

| Esteem | 9.2 ± 1.26 | 6.1 ± 2.31 | 7.8 ± 2.35 | <0.001 |

| 10 (6–10) | 6 (3–10) | 8 (3–10) | ||

| [8.55–9.76] | [4.90–7.35] | [6.99–8.56] | ||

| Job security | 8.8 ± 1.21 | 7.2 ± 1.60 | 8.1 ± 1.62 | 0.002 |

| 8 (6–10) | 7 (4–10) | 8 (4–10) | ||

| [8.26–9.43] | [6.33–8.04] | [7.54–8.62] | ||

| Effort–Reward ratio | 0.69 ± 0.19 | 1.37 ± 0.27 | 1.0 ± 0.41 | <0.001 |

| 0.70 (0.23–0.95) | 1.43 (1.00–2.04) | 0.91 (0.23–2.04) | ||

| [0.61–0.78] | [1.22–1.51] | [0.87–1.14] | ||

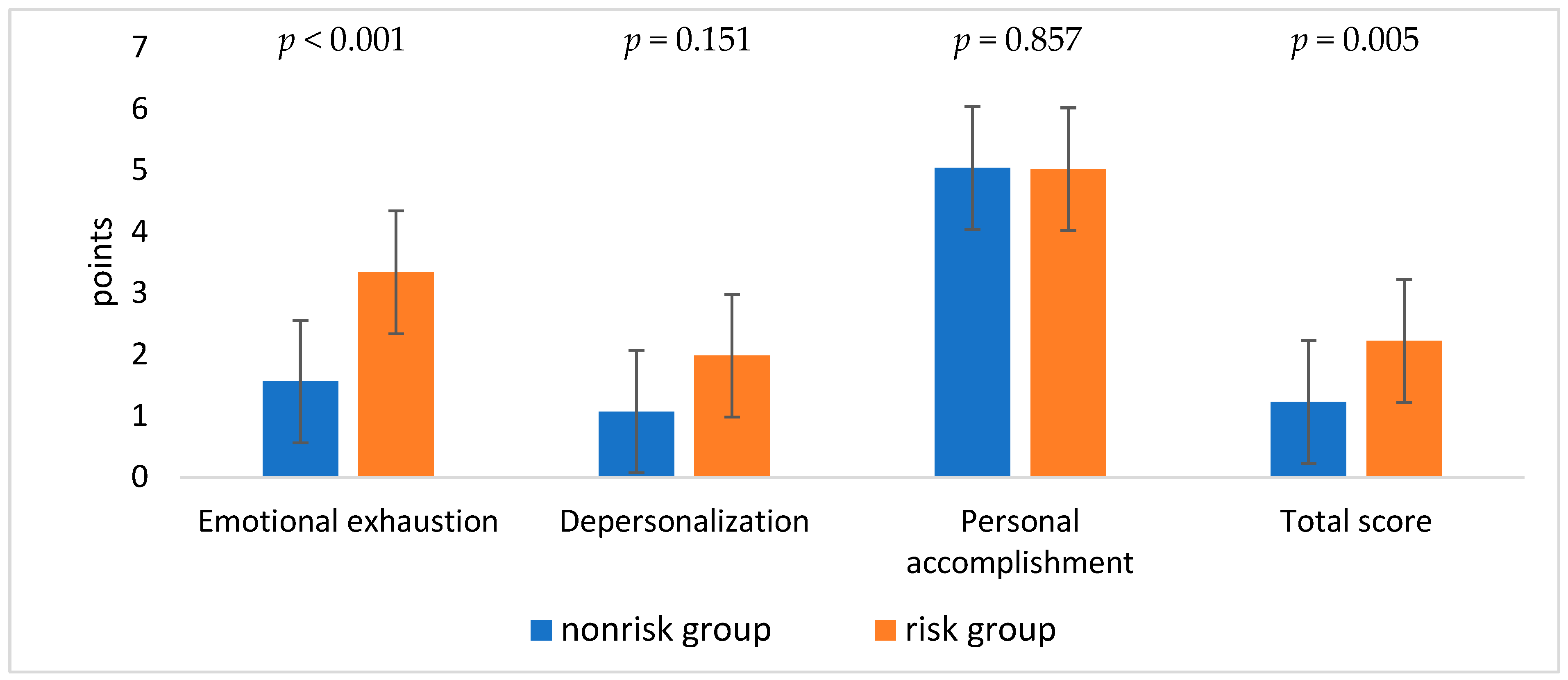

| MBI Dimensions | Degree of Expression (Range of Points) | Nonrisk Group | Risk Group | Total Sample | pχ2 bzw. Fisher exact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional exhaustion | low (≤2.00) | 15 (78.9%) | 4 (21.1%) | 19 (54.3%) | 0.002 |

| average (2.01–3.19) | 3 (15.8%) | 3 (18.8%) | 6 (17.1%) | ||

| high (≥3.20) | 1 (5.3%) | 9 (56.3%) | 10 (28.6%) | ||

| Depersonalization | low (≤1.0) | 10 (52.6%) | 6 (37.5%) | 16 (45.7%) | 0.511 |

| average (1.01–2.19) | 6 (31.6%) | 5 (31.3%) | 11 (31.4%) | ||

| high (≥2.20) | 3 (15.8%) | 5 (31.3%) | 8 (22.9%) | ||

| Personal accomplishment | low (≤4.0) | 3 (15.8%) | 2 (12.5%) | 5 (14.3%) | 0.950 |

| average (4.01–4.99) | 5 (26.3%) | 4 (25.0%) | 9 (25.7%) | ||

| high (≥5.0) | 11 (57.9%) | 10 (62.5%) | 21 (60.0%) | ||

| Risk of burnout | no burnout (0–1.49) | 13 (68.4%) | 4 (25.0%) | 17 (48.6%) | 0.012 |

| some symptoms (1.5–3.49) | 6 (31.6%) | 8 (50.0%) | 14 (40.0%) | ||

| serious burnout (3.5–6.0) | 0 (0%) | 4 (25.0%) | 4 (11.4%) |

| ERI Scales with Subscales | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBI dimensions | Effort | Reward | Job promotion | Esteem | Job security | ERI ratio |

| Emotional exhaustion | 0.468 ** | −0.385 * | −0.424 * | −0.134 | −0.318 | 0.400 * |

| Depersonalization | 0.319 | −0.390 * | −0.393 * | −0.261 | −0.190 | −0.320 |

| Personal accomplishment | −0.105 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.082 | −0.175 | −0.053 |

| Risk of burnout | 0.432 ** | −0.408 * | −0.462 ** | −0.189 | −0.217 | 0.384 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Braun, J.W.; Darius, S.; Böckelmann, I. The Correlation Between Effort–Reward Imbalance at Work and the Risk of Burnout Among Nursing Staff Working in an Emergency Department—A Pilot Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2249. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12222249

Braun JW, Darius S, Böckelmann I. The Correlation Between Effort–Reward Imbalance at Work and the Risk of Burnout Among Nursing Staff Working in an Emergency Department—A Pilot Study. Healthcare. 2024; 12(22):2249. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12222249

Chicago/Turabian StyleBraun, Justus Wolfgang, Sabine Darius, and Irina Böckelmann. 2024. "The Correlation Between Effort–Reward Imbalance at Work and the Risk of Burnout Among Nursing Staff Working in an Emergency Department—A Pilot Study" Healthcare 12, no. 22: 2249. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12222249

APA StyleBraun, J. W., Darius, S., & Böckelmann, I. (2024). The Correlation Between Effort–Reward Imbalance at Work and the Risk of Burnout Among Nursing Staff Working in an Emergency Department—A Pilot Study. Healthcare, 12(22), 2249. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12222249