1. Introduction

Individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are at higher risk for developing common chronic diseases (e.g., hypertension and diabetes), rare conditions (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, vitamin deficiency, and genetic disorders) [

1,

2,

3] and mental health problems [

4,

5] compared to the general population. Engaging in regular physical activity (PA) is recommended for people who are at greater risk for suffering from decreased health conditions [

6].

Despite these recommendations, however, people with ASD tend not to meet PA guidelines and are known to engage in lower levels of PA in comparison to their peers [

7,

8]. It is important to note that for individuals with ASD, PA has unique benefits beyond the physical and psychological benefits for the general population, such as reduced maladaptive and stereotypic ASD behaviors [

9,

10] and reduced anxiety and stress [

11]. As such, the need for developing attractive ways of engaging adult individuals with ASD in PA is of great importance.

In a recent meta-analysis [

12] that analyzed 14 case studies (13 of which had been conducted on children), the findings indicate that PA interventions were associated with positive outcomes for individuals with ASD. Additionally, the meta-analysis concluded that insufficient data currently exist for proposing optimal PA frequency, which was found to be conducted between 1 and 5 times a week for durations between 3.6 and 12 weeks in total. In an earlier meta-analysis [

13] that analyzed 8 studies (that had been conducted on children with ASD), the duration of PA intervention was found to last 4–14 weeks, with one intervention even covering 9 months.

In a recent pilot study, Savage et al. [

14] studied the feasibility of a 12-week supported self-management intervention to increase physical activity for adults with ASD and intellectual disability. They found that using a smartphone’s technology significantly improved PA engagement in addition to self-management strategies and coach support. Colombo-Dougovito et al. [

15] found in a qualitative study that social relationships were recalled as being important to the PA experiences among adults with ASD.

According to the Transtheoretical Model [

16], in order to create a behavioral change, individuals must progress through a series of five stages that occur over time: (1) precontemplation, with no intention to change behavior; (2) contemplation, becoming aware of existing problems but not taking any steps to correct them; (3) preparation, intending to take action within the next month; (4) action, attempting to modify the behavior; (5) and maintenance, working to prevent behavioral relapses. The action stage must last for a six-month period of engaging in healthy behavior before embarking on the final maintenance stage to ensure preservation of the new behavior over time. As such, PA intervention programs that last less than six months will not be able to achieve the desired goal, i.e., the long-term preservation of the behavioral change.

Considering the literature review presented above, although PA interventions are essential for adults with ASD, most studies report data about children and are short-term interventions [

9,

10,

13]. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to evaluate the effect of a long-term PA intervention on the general fitness and quality of life among adults with ASD, while examining the participants’ adherence to the program along the 12-month intervention. Based upon the literature, our hypothesis was that taking part in a long-term PA intervention of 12 months will improve general fitness as well as quality of life among adults with ASD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The PA intervention in this study was conducted in a community village where the participants live. The community village is specifically designed for people with disabilities, and accordingly, the lifestyle and activities in the place are coordinated for the residents. Three inclusion criteria were applied: (1) gender, male or female; (2) age, 20–60 years; and (3) ASD diagnosis with all levels of functioning (high functioning = no continuous support yet with social and communicational difficulties that result in prominent impairments; moderate functioning = ongoing support needed due to prominent difficulties in verbal and non-verbal social communications; and low functioning = severe difficulties in verbal and non-verbal social skills that greatly hinder normal functioning) [

17]. Moreover, two exclusion criteria were applied: (1) pre-existing health conditions, relating to any underlying or current medical condition that may constitute a contraindication for participating in a PA program without medical supervision (e.g., heart disease); and (2) cognitive inabilities, relating to profound developmental intellectual disabilities (e.g., needs are conveyed via symbolic or other non-verbal communication) [

18]. A total of 34 adults with ASD participated in the quantitative section of this study during July 2017–July 2018. Participants were recruited for the study by the physical activity guides in the community village as part of explanatory conversations held with them regarding the importance of engaging in physical activity for their health. During these conversations, the study was presented, and those who were interested were invited to participate in the study.

The sample size of the study was calculated using the effect sizes obtained in a previous study conducted by the authors, “Game for Life”, on a similar population using similar outcome measures. The average effect size of this study was 0.44. With such effect size, using t-tests (means: the difference between two dependent means) with a prior power analysis given alpha = 0.05, power = 0.80, and effect size = 0.44, a sample size of N = 34 is required. We did not add attrition to the sample size as we did not expect big attrition since all participants reside in a community village with dedicated staff members.

2.2. Measurements

Most of the quantitative data were gathered at 3 different time-points: (1) T0, at the onset of the program; (2) T1, after 6 months; and (3) T2, after 12 months, while demographic data and health status [except for body mass index (BMI)] were only evaluated at the beginning of the study.

2.2.1. Demographic, Functional, and Health Status

Each participant completed a questionnaire that included demographic questions (age, gender, family status, number of children, education, and religiousness; specific data on socioeconomic status were not recorded) and health status questions (strokes, epilepsy, respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, hematological diseases, and diabetes). ASD functional levels (high, moderate, or low) were defined for each participant according to reports provided by their social workers and based on the criteria presented for ASD severity indicated by the Israeli Society for Children and Adults with Autism [

17]. Additionally, participants’ height and weight were measured, enabling calculations of their BMI [mass (kg) × height

2 (m)].

2.2.2. Physical Fitness

To examine physical endurance, power, and flexibility, three activities were measured: (1) distance covered during a two-minute walk—participants were instructed to walk as far as they could for two minutes, and their walking distance was recorded (typical walking distance mean in adults: 65–300 m) [

19]; (2) standing long-jump—participants were instructed to place their feet over the edge of the sandpit, crouch down, lean forward, swing their arms backward and forward, and then jump as far forward as possible, landing with both feet in the sandpit. The start of the jump was from a static position. The jumping distance was measured from the near edge of the sandpit to the body’s first point of contact with the ground following the jump (average jump distance in adults: 170–230 cm) [

20]; and (3) sit-and-reach test—participants were instructed to sit on the floor with their legs stretched out straight ahead. The soles of their feet were placed flat against the testing box, with feet slightly apart at about hip-width. The participants were then instructed to keep their knees extended and reach forward with their hands as far as possible along the box, keeping both hands on the box. A standard ruler was placed on the sit-and-reach box to standardize measurements, starting at 23 cm from the heel. Reaches short of the toes were recorded as negative scores, while reaches beyond the toes were recorded as positive scores—all were recorded in cm and rounded up or down to the nearest 0.5 cm (average distance in adults: 27–37.5 cm) [

21].

2.2.3. Functional Ability

The Timed Up and Go (TUG) measure was used to assess mobility, balance, walking mobility, and fall risk. Participants were asked to stand up from a chair, walk three meters, turn around, walk back to the chair, and sit down—all at a comfortable pace. Their time for completing the test was recorded. An older adult who takes ≥12 s to complete the TUG is at risk for falling [

22].

2.2.4. Quality of Life

The Schalock Quality of Life Questionnaire for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities was employed in this study. This questionnaire addresses 4 scales (relating to satisfaction, productivity, empowerment, and social integration), each comprising 10 items. The scores were calculated for each domain (score range 1–10) and for the complete questionnaire (score range 40–120) [

23,

24].

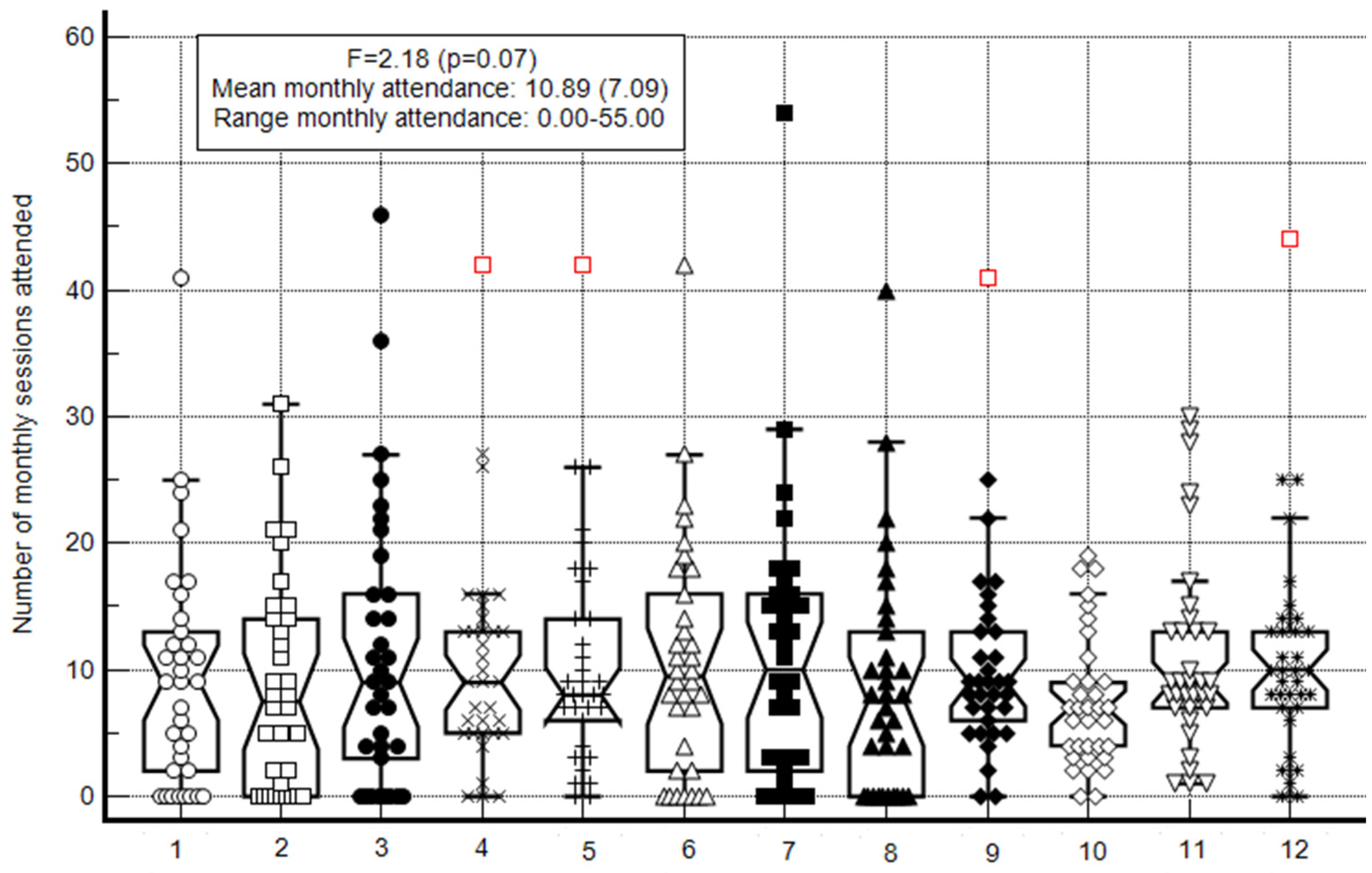

2.2.5. Program Attendance

Participant’s attendance in the program (number of monthly sessions attended—at least 60 min per session) was recorded by the program coordinator and additional staff members.

2.3. Qualitative Assessment

In addition to performing quantitative assessments, we also conducted qualitative assessments to expand our understanding of the statistical findings and to enable greater generalization of our findings [

25]. The qualitative component in this study included in-depth, semi-structured interviews that were conducted at the end of our 12-month intervention. Three staff members at the community village and three residents who participated in the study and volunteered to be interviewed took part in this session. The interviews were then examined according to the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT) analysis in relation to the success of the PA intervention program. Based on an ecological perspective of an organization within a given social and economic environment, SWOT suggests a simple and easy technique to examine the organization’s internal strengths and weaknesses, and the opportunities and threats to its environment [

25]. As such, the structured questions focused on those components. For example, the main questions asked of the staff members were: What do you consider to be the strength of your program? What are the barriers?

The analysis procedure included the following steps: First, the audio recorded interviews were transcribed. Then, each text was coded and analyzed by both authors (AD and SB) in order to improve the dependability of the analysis. The interviews were conducted as semi-structured interviews and analyzed according to a grounded theory approach. The analysis was coded with the coding of four figures observing the findings according to the SWOT model. In each of the themes, the categories corresponding to the research question were approached [

21,

26].

2.4. Procedure

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of The Levinsky-Wingate Academic College. The participants and their legal guardians signed a written informed consent form prior to participating in the study. Following the first assessment, each participant joined one or more of the following PA classes at their choosing: football or basketball (once a week for an hour), dancing (once a week for an hour), swimming (1–2 h a week), running (3–5 times a week for 1.5–2 h each time), or going to the gym (1–5 times a week for an hour each session). Most activities were presented at different time slots and more than once a week, providing the participants with a large range of options to choose from at their convenience. The activities took place in facilities (sports halls, swimming pool, and gym) located throughout the communal village. All were carried out under the guidance of a staff of professional sports instructors in the village.

2.5. Data Analysis

Normality distribution of the main continuous variables was performed using Q-Q plots. As all main variables were normally distributed, parametric statistics were used. The participants’ demographic, functional, and health status characteristics were described through descriptive statistics (mean standard deviation, range, and percentage); differences in the prevalence of categorical variables were assessed using chi-squared tests. Changes in their fitness, functional ability, and quality of life—assessed at three different time-points—were evaluated using repeated measures analysis of variance with Tukey’s range post-hoc tests. In addition, Cohen’s d-effect size (mean ∆/standard deviation average from two means) was calculated in order to examine the extent of changes from the T0 to T2. A correction for the dependence among means was conducted using the correlations between the two means following Morris and DeShon’s equation [

27]. Generally, values <0.20 were considered as trivial effect sizes, between 0.20 and 0.50 as small effect sizes, between 0.51 and 0.80 as moderate effect sizes, and >0.80 as large effect sizes. Pearson correlations between T0 and T2 in each variable were also calculated.

Participant’s attendance was calculated for each of the 12 intervention months and then utilized to examined how many months the participant had attended at least 10 PA sessions that month (i.e., the number of monthly sessions attended) using the Box-and-Whisker plot. Next, descriptive statistics of the number of months with sufficient attendance (i.e., 600 min per month—as per recommendations issued by the American College of Sports Medicine [

6]) were calculated and are displayed using the Box-and-Whisker plot. Moreover, the percentage of participant attendance in each of the 12 intervention months was calculated and the results for two groups, sufficient attendance vs. insufficient attendance, were compared using chi-squared tests.

Gender (males, females), religiousness (secular, traditional), functional level, and differences in the mean number of sufficient monthly attendance were compared using independent t-tests (for dichotomized variables) or one-way analysis of variance (for non-dichotomized variables). For the continuous variables (age, number of children, BMI, number of chronic diseases, fitness measures, functional measures, and quality of life), associations with the number of months with sufficient attendance were evaluated using Pearson correlations.

Finally, post-hoc power analysis was conducted. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of a long-term PA intervention on general fitness and quality of life among adults with ASD. Therefore, in order to calculate the study’s power, effect sizes and repeated measures correlations in all the dependent variables (T0 vs. T2) were calculated. The mean effect size observed and the mean repeated measures correlations were 0.44 and 0.49, respectively. Based on these parameters, using F tests for family and ANOVA repeated measures with within-factors design, with a sample size of N = 34, one group, and three measurements, the achieved power is 0.90.

For all statistical analyses, SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05 (2-tailed). Only power analysis was conducted using G*Power software, version 3.1.9.2.

4. Discussion

The main finding of the current study shows that the current long-term PA intervention improved the aerobic fitness and several components of quality of life of adults with ASD. In this regard, it is important to note that participants were able to choose from different types of activities. Each activity has unique social and physical fitness demands and effects. For example, football requires social interaction, which in turn might have an enhanced influence on aspects related to psychological aspects such as quality of life. In addition, football is a very demanding sport in terms of physical fitness requirements (e.g., aerobic fitness and lower extremity strength). In contrast, swimming, although also demanding in terms of physical fitness requirements, is an individual sport and therefore might have a different effect on psychological aspects such as quality of life. Despite the anticipated different effects, the overall aim of the study was to develop a feasible program with high long-term attendance, resulting in increased PA level. The current intervention that was based on participants’ free choice to select between a range of PA classes, offered at convenient time slots during the day and promoted by significant people for the studied population, led to increased PA adherence, in line with the recommended amounts suggested by global health organizations [

6]. This finding greatly contributes to the literature, as it addresses adherence of adults with ASD to health-related requirements over an entire year.

Motivation or lack thereof to engage in PA is a major psychological factor that enhances or hinders adherence, with a lack of motivation being considered a significant barrier among young individuals with ASD to engage in PA [

12]. Moreover, motivation to perform PA among young adults with ASD is positively associated with three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Thus, it has been suggested that practitioners should provide an environment where young adults with ASD can enjoy close relationships with staff members and peers within programs that are based on improving autonomy and competence [

28]. In the current study, the participants could choose their PA classes based on their own desire and schedule. As such, autonomy and free choice served as a basic guideline throughout the program. Similar results were found among children, indicating that the relative efficacy of a program can be influenced by the number of alternative stimuli available [

29]. Moreover, our qualitative analysis indicates that participants who felt that they are part of a “prestige club” after being accepted onto the running club exhibited higher motivation to continue with the program and improve their running performance. Additionally, when interviewing staff members and PA instructors, it seems that personal, almost individual instruction during PA classes (such as in the gym, where almost every participant had their own instructor, or during one-on-one swimming lessons) led to higher motivation among the participants and in turn, to higher adherence.

Relatedness that was found to be associated with well-being [

30] may explain the improvement found in the current study, in the satisfaction and total score components from the Schalock Quality of Life Questionnaire, which assesses quality of life and well-being. It is possible that as the participants felt related to their peers in the activity group or to their trainers/coaches, as revealed in the interviews, they experienced improved satisfaction from life in general. This possibility is in line with previous results [

31], whereby the ability to share feelings with “like-minded” others led to increased feelings of satisfaction among participants. These researchers also found that adults with ASD had a sense of well-being and belonging when they felt connections with others in their group. Our results are also in line with previous findings about many of the challenges faced by people with ASD in achieving well-being and belonging. It was found that the most frequent ways for people with ASD to achieve quality of life are by meeting personal needs within social settings, by achieving the impact of societal othering, by finding connection and recognition, and by managing relationships with friends and family [

31].

The perseverance of the participants in the PA classes was also found to be associated with significant improvement over a six-month period in one fitness component, i.e., the two-minute walk test, from T0 to T1. These findings are in line with previous studies, whereby perseverance is associated with improved aerobic fitness following prolonged adherence to aerobic PA programs, such as swimming, running, or walking, among youth with ASD, where associations were seen between improved PA levels, skill-related fitness, muscular strength, and endurance [

32]. In the current study, however, several fitness components did not improve during the 12-month intervention program, including muscular strength (measured via the standing long-jump), flexibility of the lower back and lower extremities (measured via the sit-and-reach test), and the mobility functional performance (measured via the TUG test). As such, future intervention programs could benefit from addressing these specific components in the PA classes that are offered to the participants.

Based on the qualitative analysis of the current study, it is assumed that there are several strength factors that enabled the impressive adherence of the participants. One of them is freedom of choice among PA modalities and schedules. The freedom of choice is of special importance; while external factors such as changes in physical appearance motivate people to begin exercising, enhancing their intrinsic motivation by freedom of choice is a key factor in promoting exercise adherence [

33]. Moreover, freedom of choice might enhance participants’ sense of competence, autonomy, and relatedness attached to the physical activity they conducted, which in turn increases their adherence. Additional important factors that might have a positive impact on adherence are the dedication of the coordinator and the staff members, and a dedicated budget that enables the purchase of additional fitness equipment and the payment of staff salaries. Based upon the transtheoretical model [

16], it is possible that this decision-making shaped the choices made in continuing, relapsing, or modifying PA behaviors by taking part in different PA modalities or schedules. However, it is essential to note that other factors that were not examined in the current study might also influence participants’ adherence to the program, such as the physical environment, social support, and support from caregivers [

34]. Regarding this possibility, from the interview with the program coordinator, it emerged that many times, the participants’ decisions to join the physical activity training were influenced by the social workers. This fact seems to imply that the village managers and social workers should examine ways of encouraging independent decision-making by the participants.

In the interviews, the budget was mentioned both as a strength of the program (i.e., funding was achieving for the 12-month intervention program) and as a possible weakness and even threat of the program (i.e., new funding needs to be achieved in order to keep the program going). Similar factors were raised by Arnell et al. [

35], who interviewed professionals from several aspects (education, health care, community, and sports organizations) about ways to promote physical activity in adolescents with ASD. Their results suggested that promoting PA habits in adolescents with ASD was difficult due to their need for tailored activities as well as other competing demands and limited resources. The program coordinator in the current study is determined to maintain this program, continuously seeking new sources of funding and additional volunteers—even on a weekly basic. In other words, a central component in the project’s success seems to be the dedication of the people who lead it. This finding highlights the importance of implementing a policy of funding health-promotional activities, such as the one proposed in the current study, by political bodies.

It is important to note that despite the general positive adherence that was found in the study, several issues still need to be addressed. For example, during the 12 months of the program, some participants did not attend any activity at all; thus, the coordinator and the social workers had to follow those participants more excessively. Additionally, there were two sub-groups of participants that exhibited lower levels of attendance: females (compared to males) and individuals with low functional levels (compared to those with medium or high functional levels). While these results are in line with previous studies [

12], additional specific strategies are needed to enhance the attendance for those specific groups and decrease health risks among these populations.

The findings of this study are beneficial to all people involved in promoting programs for adults with ASD, including individuals themselves. However, several limitations should be addressed in interpreting and generalizing this study’s findings. First, the intervention program was conducted in a community village where the participants were recruited. It is possible that the results revealed in the current study are specific to this village. As such, future research could benefit from conducting similar intervention programs in several community villages, enabling greater generalization of the results. Next, the PA classes offered and their physical outcomes may not have been in line with the fitness tests conducted (such as the sit-and-reach test), and different tests may yield different or additional findings. The number of participants who took part in this study was relatively small, and as each participant was her/his own control, there was no “control group”. As such, future research could benefit from conducting a similar study on a larger scale of quantitative and qualitative participants. Another limitation pertains to the fact that participants had a free choice of selected physical activity types. As a result, it is difficult to evaluate the unique effects of each activity on physical development. Future studies, with bigger sample sizes, should aim at investigating the relative contribution of various types of activities. Finally, the fact that in the current study, there was no control group that did not exercise during the intervention period, may be an obstacle in generalizing the findings to the entire population of adults with ASD. However, it is important to note that as participants in the study were adults, natural improvements in the fitness parameters that showed improvement in the current study were not expected. Additionally, as the current population is known to have a high risk for deterioration in all fitness and health parameters assessed in the study, it is reasonable to assume that the improvements found in the current study were possible effects of the intervention. As it is not ethical to ask for a control group that will not exercise, future studies should compare the current intervention with other forms of physical activities (i.e., personal training versus group activities) and among people with ASD living in more open environments (and not in a specialized community village as was assessed in the current study). We also suggest exploring the current intervention among people with greater cognitive difficulties.