Abstract

Masturbation is a healthy sexual behavior associated with different sexual functioning dimensions, which highlights sexual satisfaction as an important manifestation of sexual wellbeing. This review aims to systematically examine studies that have associated masturbation with sexual satisfaction, both in individuals with and without a partner. Following the PRISMA statement, searches were made in the APA PsycInfo, Medline, Scopus, and Web of Science databases. The search yielded 851 records, and twenty-two articles that examined the relation between solitary masturbation and sexual satisfaction were selected. In men, a negative relation between masturbation and sexual satisfaction was observed in 71.4% of the studies, 21.4% found no such relation, and 7.2% observed a positive association. In women, 40% reported no relation, 33.3% a negative relation, and 26.7% a positive one. The negative association between solitary masturbation and sexual satisfaction is consistent with the previously proposed compensatory role of masturbation, especially for men. In women, compared to men, the complementary role of masturbation in relation to sexual relationships is observed to a greater extent and is associated more closely with sexual health. The importance of including different parameters beyond the masturbation frequency in future studies to explore its relation with sexual satisfaction is emphasized. This systematic review is registered in PROSPERO (CRD42023416688).

1. Introduction

Masturbation is a healthy sexual behavior practiced with others (e.g., a partner) or individually [1]. Solitary masturbation is defined as erotic self-stimulation without anyone else being present or participating [2]. Its practice is present from very early development phases to old age [3]. This behavior favors self-exploration and sexual learning in a context in which the presence of sexual difficulties might be less prevalent [4]. Previous studies have stressed the importance of solitary masturbation for the adjustment and generalization of the sexual response to the context of sexual relationships [5], acting as a therapeutic tool to deal with some sexual difficulties [6,7].

The relation of solitary masturbation with sexual relationships has been studied mostly by two models: compensatory and complementary. The compensatory model hypothesizes that masturbation frequency could increase for the purpose of substituting unsatisfactory or insufficient sexual relationships [8,9]. The complementary model considers a positive relation between masturbation behavior and sexual relationships, implying that practicing one would be associated with the other one being practiced more frequently [9]. Previous pieces of evidence suggest that the compensatory pattern would be more present in men, with the complementary pattern in women [9,10,11,12,13,14], despite some studies showing the independence of gender in both of these models [15,16].

Masturbation has been related to different sexual functioning dimensions, although very few results have been obtained. Positive associations have been described with sexual desire [17], sexual arousal [11], or orgasm [5], which evidences the positive implication of this behavior in sexual response. One of the most interesting dimensions is sexual satisfaction, which is an important indicator of sexual health [18,19,20].

Sexual satisfaction could be considered the last phase of the sexual response cycle according to Basson’s model [21,22] and is defined as “an affective response arising from one’s subjective evaluation of the positive and negative dimensions associated with one’s sexual relationship” [23] (p. 268). Its study requires a multidimensional approach that contemplates personal, interpersonal, and social factors [19,24]. In line with this, the Ecological Theory of Human Development [25] has served as a guide to study it by bearing in mind the different associated relevant variables, which range from the closest to the most distant to an individual [19]. Of the variables associated with sexual satisfaction, solitary masturbation falls under personal-type factors [13,26,27].

As far as we are aware, the pieces of evidence that have associated solitary masturbation with sexual satisfaction have not been integrated, despite its importance for sexual health. Thus, considering that previous literature reviews on this are missing, the objective of the present study is to systematically analyze the results obtained in the scientific literature about the relation between solitary masturbation (i.e., its presence/absence and/or frequency) and sexual satisfaction, including a comparison of this relation in men and women.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Guidelines (PRISMA) [28]. The protocol of this review is registered in PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42023416688).

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

To fulfill the objectives of this systematic review, the considered studies had to address the relation between solitary masturbation and sexual satisfaction. Eligible studies had to meet all the following inclusion criteria: (a) original research articles; (b) solitary masturbation (as presence/absence or frequency); (c) sexual satisfaction was assessed using standardized instruments, ad hoc items, or derived from scales, questionnaires, or interviews; (d) they had examined the direct and indirect relation, considering mediators and/or covariates between solitary masturbation and sexual satisfaction.

There was no limitation for publication year, and the English and Spanish languages were considered.

2.2. Information Sources

The literature search was conducted on APA PsycInfo, Medline, Scopus, and Web of Science. The last database query date was 30 October 2023.

2.3. Search Strategy

Following the recommendations by Quevedo-Blasco [29] and using the terms related to sexual satisfaction as employed in the systematic review by Sánchez-Fuentes et al. [19], the search strategy integrated the following terms: (masturb* OR self-stimulat* OR onanism* OR “solitary sexual activit*”) AND (“satisfac* sex*” OR “sex* satisfact*” OR “satisfaction with sex*”), using the truncation “*” to include any variant of words.

To validate the search strategy, a peer review was conducted by proofreading the syntax, spelling, and structure and ensuring that the search formula identified articles that were relevant to the search. The formula was applied to the title, abstract, and/or keywords, or, if applicable, to the topic, to narrow down the search on the topic of masturbation and sexual satisfaction.

2.4. Selection Process

The search results were exported on the Rayyan online platform, a web-based automated screening tool developed by the Qatar Computing Research Institute (QCRI) that is accessible at www.rayyan.ai (accessed on 15 November 2023) [30]. This export included the title, authors, publication date, abstract, and keywords. Two authors (AÁM and OC) independently reviewed the documents based on their title, abstract, and keywords by categorizing articles as included, doubtful, or rejected. The studies labeled as doubtful underwent a full-text review, and discrepancies were solved by consensus. Final decisions, if necessary, were made by a third researcher (JCS).

2.5. Data Collection Process

The articles that met the inclusion criteria were comprehensively read independently by two reviewers to guarantee the objectivity and rigor of the results. A data collection form was designed, and the extracted data were compared to any discrepancies resolved by discussion. The extracted data included: (a) authors, (b) country, (c) sample, (d) participants’ sexual orientation, (e) instrument used to assess solitary masturbation, (f) instrument applied to assess sexual satisfaction, and (g) results about the association between masturbation and sexual satisfaction. The true Kappa value was employed to assess the reliability of coding [31,32]. Intercoding was evaluated by indicating agreement or disagreement in the analyses of the categories extracted during the article selection process [33]. A true Kappa value of 0.91 was obtained when considering the agreement between coders to be satisfactory with a Kappa value above 75%.

2.6. Data Items

Outcome measures that assess (a) solitary masturbation and (b) sexual satisfaction were extracted. The results can be reported as the presence/absence of solitary masturbation by dichotomous items, a frequency scale of solitary masturbation, or interviews. Likewise, an overall test score to provide a general measure of sexual satisfaction (e.g., general sexual satisfaction) or subscales/specific items to provide a measure of domain-specific sexual satisfaction (i.e., physical sexual satisfaction) was/were considered.

2.7. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

The risk of bias in the included studies was assessed using the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (QATOCCS) [34] for those studies that indicated a quantitative methodology and the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) [35] tool for the studies that indicated an observational analytical methodology. These tools provided a standardized framework for assessing the scientific rigor of all the reviewed studies through a checklist of requirements (e.g., definition of the study population, the research question, control definition, inclusion criteria, blindness, and the reporting of confounders). The evaluation ensured the studies’ robustness and the results’ reliability. To do so, two authors independently applied the tools to the included studies. If discrepancies arose, they were solved by consensus.

2.8. Synthesis Methods

Table 1 shows the individual results of the studies and the synthesis. For better visualization purposes, the authors, publication year, country, sample size, assessment of masturbation and sexual satisfaction, and the main findings about the relation between both variables were tabulated.

Table 1.

Summary of study reviews about the relationship between solitary masturbation and sexual satisfaction.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

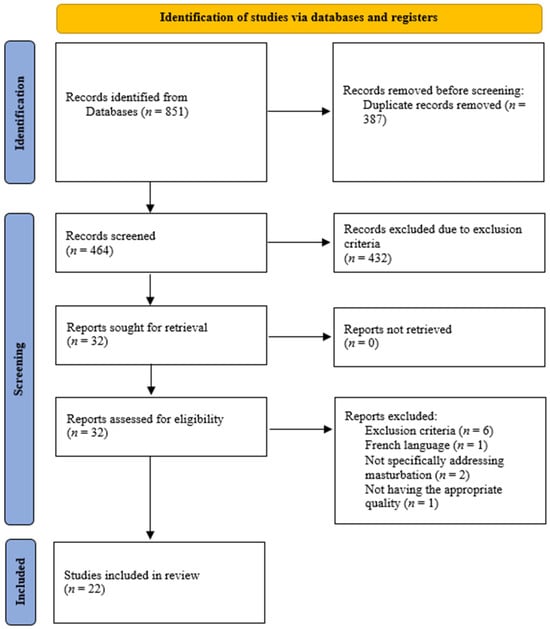

The database search yielded 851 records (see Supplementary Data S1). After eliminating duplicates, 464 records remained according to their title, abstract, and keywords. Of these, 432 records were excluded due to the exclusion criteria. A total of 32 underwent a full-text examination, and, finally, 10 were eliminated because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. To broaden the selection process, although a search was made for the papers cited in the studies to be considered, none of them were included. This left 22 papers that met the inclusion criteria and methodological quality standards and could, therefore, be included in the present systematic review. Figure 1 shows a flow chart of the selection process for these studies.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for the systematic review of searches of databases.

Below are the results of the 22 analyzed papers that evaluated the relation between solitary masturbation and sexual satisfaction (see Table 1).

3.2. Sociodemographic Characteristics

The studies were conducted in one or more of these countries: the United States (5 publications), Norway (4), Brazil (2), Switzerland (1), Sweden (1), Denmark (1), Belgium (1), Portugal (1), Hungary (1), the Czech Republic (1), the United Kingdom (1), Australia (1), Malaysia (1), China (1), Canada (1), and Germany (1).

Seventeen of the twenty-two papers included both men and women samples [12,15,16,37,41,46,47,48,49,55,57,59,62,64,65,66,68], while four papers were conducted exclusively with women [36,40,42,44] and one with men [53]. Three studies reported exclusively heterosexual participants [47,48,53], and six also included populations of other sexual orientations (e.g., gay or bisexual) [16,41,42,46,55,66]. The rest of the studies did not report their participants’ sexual orientation.

3.3. Instruments to Assess Masturbation

Most of the studies used ad hoc procedures to assess masturbation: frequency scales and, to a lesser extent, a dichotomous item or an interview to determine presence/absence. Only three papers employed an item drawn from validated scales or found in previous projects to assess masturbation frequency [12,46,47]. The time frame to which masturbation practice referred, in those studies that indicated it, was variable: in the last 24 h [66], in the last month [12,36,37,46,59,65], in the last 6 months [41,49,53], or in the last year [15,42].

Regarding the response scale, except for two studies in which presence/absence was evaluated dichotomously (i.e., having masturbated vs. not having masturbated) [15,66] and one in which the response was free (i.e., indicate the number of times) [36], in the remaining papers that specified it, Likert-type response scales of three [59], four [55], five [48], six [16,41,49,68], seven [12,46,57], eight [53,62], nine [42,44], and ten [64] categories were used.

3.4. Instruments to Assess Sexual Satisfaction

Sexual satisfaction was assessed in twelve of the studies using ad hoc items on satisfaction with sexual relationships and/or sex life [12,15,16,36,40,41,46,47,48,49,64,68], answered with a Likert-type scale, except for two studies that employed dichotomous items (i.e., satisfied vs. not satisfied) [15,40].

Four papers employed items drawn from one of the following validated instruments or more: the Life Satisfaction Scale [38,39], the Multidimensional Sexuality Questionnaire (MSQ) [45], the Female Sexual Function Inventory (FSFI) [63], the Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (CSFQ) [61], the Satisfaction with Sex Life Scale—Revised [58], and the Derogatis Interview for Sexual Functioning (DISF-SR) [60].

The remaining six papers used standardized assessment instruments: the Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction [54] the Female Sexual Quotient [43], which were both included in two papers, the Male Sexual Quotient [56], and the Multidimensional Sexuality Questionnaire (MSQ) [45].

3.5. Relation between Masturbation and Sexual Satisfaction

Five studies (22.7%) examined the relation between masturbation and sexual satisfaction in men and women together. They revealed a negative relation [55,57,62,68] or no relation [57,66] between both variables.

Of the studies with samples exclusively made up of men or that examined men independently of women, 71.4% of them (ten articles) reported a negative relation between masturbation and sexual satisfaction [12,16,37,41,44,47,49,53,59,64]. In contrast, three studies (21.4%) found no significant relation between the two variables [46,48,65], and a single study (7.2%) observed a positive association between masturbation and sexual satisfaction [15].

Of the studies with samples formed exclusively of women or that examined women independently of men, six (40%) indicated no relation between masturbation and sexual satisfaction [40,41,46,48,59,65], five studies (33.3%) reported a negative relation [12,16,36,37,44], and four (26.7%) showed a positive relation [15,42,46,49].

4. Discussion

Solitary masturbation is a behavior with implications for sexual health, among which sexual satisfaction is included. To integrate the results obtained from the scientific literature about the relation between solitary masturbation and sexual satisfaction, this study presents a systematic review of the articles published up to October 2023. Most of the studies included in the review (63.6%) were conducted in the United States and Europe. This aligns with the increasingly positive view in western countries that solitary masturbation is considered to be a source of pleasure that is independent of sexual relationships [1,3,10,69]. The evolution toward a positive view of this behavior in recent years has promoted further research, which is reflected by the publication year of the works included in this systematic review because most had publication dates in the last two decades. Nevertheless, masturbation experiences can be positive or negative, depending on prevailing social attitudes [1]. The cultural divide observed in this review could be evidence of the challenges in the area of research into sexuality that some societies face, such as African ones, where difficulties are reported for people to share some aspects related to their sexuality [70]. Masturbation is still taboo in some of these societies, which contributes to the limited discussion on the topic and the proliferation of many misconceptions about the effects of masturbation, implying disinformation [71].

Most of the participants in the reviewed studies are heterosexuals, which agrees with what has been generally observed in the sexuality research area [72]. This scenario reveals that sexual minorities are less represented. In this regard, the importance of integrating groups affected by social stigma in research is highlighted [73].

Solitary masturbation was assessed mostly with one ad hoc item that identified the presence/absence of masturbation or its frequency. Masturbation frequency has been stressed as a relevant measure for investigating masturbation [26,74]. This relevant parameter is related to significant indicators of sexual well-being, highlighting its relevance to sexual functioning. In women, the frequency of masturbation is positively related to orgasm pleasure [75] and to the greater facility of reaching orgasm in older women [74]. In men, more frequent masturbation is associated with more difficulty reaching an orgasm [74] and more symptoms of retarded ejaculation [76]. Therefore, this parameter has contributed to expanding scientific knowledge about masturbation and delving deeper into the study of this behavior [2]. However, we should bear in mind the diversity of time ranges and the responses employed to measure this parameter when comparing and generalizing the results reported in the present systematic review.

Sexual satisfaction was often assessed with ad hoc items about the level of experienced satisfaction. This matter has been criticized by Sánchez-Fuentes et al. [19]. Using a single item can present measurement stability problems [77], and it may generate sources of error when simplifying the evaluated construct [78]. Four works employed items taken from standardized scales, which does not guarantee suitable psychometric properties for the original instrument. Only 27% of the studies evaluated sexual satisfaction using standardized scales, which ensure that acceptable and reliable measures are obtained [79]. Of these scales, the Female Sexual Quotient [43], the Male Sexual Quotient [56], and the Multidimensional Sexuality Questionnaire (MSQ) [45] appeared. We stress the Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction [54], used in two studies. It is a measure included in the Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire (IEMSSQ) [80] that derives from the Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction (IEMSS) [23], a theoretical consolidated model of sexual satisfaction [67] that has been validated in Spain [81,82], Canada [23], and the United States [83]. Considering the complexity of the conceptualization of sexual satisfaction and the diverse ways of assessing it [84], it is highly relevant to integrate its definition to compare and delve into the study of this sexual functioning dimension [85].

In relation to the obtained findings about the relation between solitary masturbation and sexual satisfaction, the studies that jointly considered men and women pointed out a negative relation between solitary masturbation and sexual satisfaction [55,57,62,68] or no relation [57,66]. Despite some studies including gender as a covariable (e.g., [57,62]), the results must be cautiously considered given the known differences between men and women in the various parameters associated with masturbation [26,74,86,87,88,89,90].

The findings in those studies that examined the relation between solitary masturbation and sexual satisfaction in men and women separately are more interesting. Most of the studies (71.4%) that have dealt with this association in men reported a negative relation between solitary masturbation and satisfaction, as opposed to 21.4% of them that did not find a significant relation and the 7.2% that reported a positive association. Thus, a negative relation was observed mostly for men, which contrasts with the evidence showing that masturbation is a positive indicator of sexual health [1] and practicing masturbation is related to different beneficial health aspects (e.g., [91,92,93]). One of the main hypotheses that could explain this finding in men stems from the compensatory model of masturbation [8,15]. This model proposes that people resort to this behavior as a substitute for sexual dissatisfaction. Previous evidence reveals that the compensatory pattern of masturbation might be more characteristic of men than women [9,12,13,14]. To support this hypothesis, more men compared to women have reported having less desire to masturbate [94] and show a more negative attitude toward masturbation at older ages [74]. This stresses the importance of considering the negative attitude toward masturbation (see [95]) when studying this behavior to understand its implication in the sexual satisfaction experience. This finding could also be interpreted in line with the hypothesis put forward by Rowland et al. [64]. According to their hypothesis, people who masturbate may exhibit a strong auto-erotic orientation, which could make this behavior more gratifying than sexual relationships. This proposal is coherent with evidence showing that men report more solitary sexual desire than women [26,74,86], they report a higher masturbation frequency (e.g., [74,88]), and among the various reasons for practicing this behavior, sexual pleasure stands out [96]. So it is proposed that future studies which examine the relation between solitary masturbation and satisfaction should include the reasons why masturbation is practiced as a mediator variable.

The studies performed with women reflect, to a greater extent, the heterogeneity of the obtained results: 40% found no relation between solitary masturbation and sexual satisfaction, 33.3% found a negative association, and 26.7% pointed out a positive relation between both variables. This greater heterogeneity of the results obtained for women might have something to do with their sexuality compared to that of men, which is generally determined by a larger number of variables [26,97,98,99], as specifically noted for sexual satisfaction [100]. One third of the studies performed with women found a negative association between solitary masturbation and sexual satisfaction. This reveals that sexual dissatisfaction could also be a reason for them to practice masturbation [93]. Masturbating could be an indicator of feeling comfortable about one’s body and sexuality, which could raise awareness about dissatisfaction or reduce the likelihood of someone exaggerating their sexual satisfaction during sexual relationships [40]. The percentage of the studies that report a positive association between solitary masturbation and sexual satisfaction was higher in women (26.7%) than in men (7.1%). In recent decades, inhibition about female sexuality may have lowered [11,15], which would reflect the empowerment role of masturbation noted in women [101,102].

The inconsistency encountered in the obtained results could be partly due to the diversity of the employed measures, and very few of the research works assessed sexual satisfaction with instruments based on robust theoretical models that have demonstrated their invariance in the population of interest. As previously mentioned, the cultural diversity in accepting and practicing masturbation could also be a source for the variation in the results [3], as could considering neither a negative attitude toward masturbation nor the reasons for masturbating to be covariables. Not all the studies contemplated interpersonal-type variables, such as satisfaction with one’s relationship, which has been associated with both practicing masturbation [94] and sexual satisfaction [100]. Other covariables that should be considered are age, given that this behavior evolves with generational advancement [10,11,14,69], having a partner because of its association with masturbation practice [9,10], and sexual satisfaction [59]. In the exploration of the distinction between being single or in a relationship, it has been observed that in the two studies focusing exclusively on single individuals, no significant association between masturbation and sexual satisfaction was found [40,57], while in the studies that considered exclusively samples of couples, they found a positive (e.g., [15]), negative (e.g., [57]), or no relation (e.g., [66]). These findings should be approached with caution due to the diversity of terminology employed (i.e., partner, sex partner, couple, in a relationship) and the limited evidence found in single people. The importance of further study of the relation between masturbation and sexual satisfaction in single individuals is highlighted [57].

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the results must be cautiously considered because the experimental design type of the reviewed studies does not allow case–effect relations to be established. To interpret the findings of our systematic review, it is necessary to bear in mind that the reviewed studies were original scientific articles written only in Spanish and English. Thus, this systematic review did not consider other languages, types of investigations (e.g., narrative and qualitative), or other reviews. As mentioned above, the diverse criteria for masturbation frequency (e.g., the past 30 days or 6 months), the different instruments used to assess sexual satisfaction, and the sample used (mostly heterosexuals) could influence the generalizability of the results.

5. Conclusions

Our systematic review evidences the relation between solitary masturbation and sexual satisfaction. Although its findings in favor of a negative association are present, considering sexual differences is absolutely necessary. Thus, a more consistent pattern of negative relations is found in men, which supports the compensatory role of masturbation. Conversely, the results for women are more heterogeneous, and there are more pieces of evidence for a positive relation than for men. This finding suggests that solitary masturbation for women could be an indicator that is more related to sexual health, which would support the complementary role between both behaviors (solitary masturbation and sexual relationships). It is necessary to continue research to examine in more depth the association between masturbation and sexual satisfaction, considering partnered masturbation. In future studies, given the relevance of masturbation to sexual satisfaction, it could also be interesting to examine how different patterns of sexual activity (including solitary masturbation and sexual relationships) are associated with sexual satisfaction in a romantic relationship. It would also be relevant to use a validated theoretical model of sexual satisfaction that would also include solitary masturbation frequency and other important parameters like age of masturbation onset, reasons for masturbating, and specific measures that characterize the subjective orgasm experience achieved by masturbation or taking a negative attitude toward this behavior.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare12020235/s1: Supplementary Data S1: Records identified from databases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.S.; methodology, O.C., A.Á.-M. and J.C.S.; investigation, O.C., A.Á.-M. and J.C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, O.C., A.Á.-M. and J.C.S.; writing—review and editing, O.C., A.Á.-M. and J.C.S.; and funding acquisition, J.C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades through the research project RTI2018-093317-B-I00 and the bursary FPU18/03102 for university professor training as part of the first author’s thesis (Psychological Doctoral Programme B13 56 1; RD 99/2011).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ford, J.V.; Corona-Vargas, E.; Cruz, M.; Fortenberry, J.D.; Kismodi, E.; Philpott, A.; Rubio-Aurioles, E.; Coleman, E. The World Association for Sexual Health’s declaration on sexual pleasure: A technical guide. Int. J. Sex. Health 2021, 33, 612–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, A.L.; Peterson, Z.D. Would you say you “had masturbated” if … ?: The influence of situational and individual factors on labeling a behavior as masturbation. J. Sex Res. 2018, 55, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Træen, B.; Štulhofer, A.; Janssen, E.; Carvalheira, A.A.; Hald, G.M.; Lange, T.; Graham, C. Sexual activity and sexual satisfaction among older adults in four European countries. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2019, 48, 815–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowland, D.L.; Hamilton, B.D.; Bacys, K.R.; Hevesi, K. Sexual response differs during partnered sex and masturbation in men with and without sexual dysfunction: Implications for treatment. J. Sex. Med. 2021, 18, 1835–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, E. Psychological and behavioral treatment of female orgasmic disorder. Sex. Med. Rev. 2021, 9, 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laan, E.; Rellini, A.H. Can we treat anorgasmia in women? The challenge to experiencing pleasure. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2011, 26, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rullo, J.E.; Lorenz, T.; Ziegelmann, M.J.; Meihofer, L.; Herbenick, D.; Faubion, S.S. Genital vibration for sexual function and enhancement: A review of evidence. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2018, 33, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Parish, W.L.; Laumann, E.O. Masturbation in urban China. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2009, 38, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnerus, M.; Price, J.; Gordon, D. Masturbation and partnered sex: Substitutes or complements? Arch. Sex. Behav. 2017, 46, 2111–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burri, A.; Carvalheira, A. Masturbatory behavior in a population sample of German women. J. Sex. Med. 2019, 16, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalheira, A.; Leal, I. Masturbation among women: Associated factors and sexual response in a Portuguese community sample. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2013, 39, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, N.; Graham, C.A.; Træen, B.; Hald, G.M. Prevalence of masturbation and associated factors among older adults in four European countries. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2022, 51, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, N.; Træen, B. A seemingly paradoxical relationship between masturbation frequency and sexual satisfaction. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2022, 51, 3151–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerressu, M.; Mercer, C.H.; Graham, C.A.; Wellings, K.; Johnson, A.M. Prevalence of masturbation and associated factors in a British national probability survey. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2008, 37, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A. Masturbation in the United States. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2007, 33, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velten, J.; Margraf, J. Satisfaction guaranteed? How individual, partner, and relationship factors impact sexual satisfaction within partnerships. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamboni, B.D.; Crawford, I. Using masturbation in sex therapy: Relationships between masturbation, sexual desire, and sexual fantasy. J. Psychol. Hum. Sex. 2003, 14, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A.W.; Lehavot, K.; Simoni, J. Ecological models of sexual satisfaction among lesbian/bisexual and heterosexual women. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2009, 38, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fuentes, M.M.; Santos-Iglesias, P.; Sierra, J.C. A systematic review of sexual satisfaction. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2014, 14, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Measuring Sexual Health: Conceptual and Practical Considerations and Related Indicators. 2010. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70434/who_rhr_10.12_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 2 July 2023).

- Basson, R. Using a different model for female sexual response to address women’s problematic low sexual desire. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2001, 27, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, J.C.; Buela-Casal, G. Evaluación y tratamiento de las disfunciones sexuales. In Manual de Evaluación y Tratamientos Psicológicos, 2nd ed.; Buela-Casal, G., Sierra, J.C., Eds.; Biblioteca Nueva: Madrid, Spain, 2004; pp. 439–485. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrance, K.A.; Byers, E.S. Sexual satisfaction in long-term heterosexual relationships: The interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. Pers. Relat. 1995, 2, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvillo, C.F.; Sánchez-Fuentes, M.M.; Sierra, J.C. Systematic review on sexual satisfaction in same-sex couples. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Salud 2018, 9, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological models of human development. In The International Encyclopedia of Education, 2nd ed.; Husten, T., Postlethewaite, T.N., Eds.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 1643–1647. [Google Scholar]

- Cervilla, O.; Sierra, J.C. Masturbation parameters related to orgasm satisfaction in sexual relationships: Differences between men and women. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 903361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurlbert, D.F.; Whittaker, K.E. The role of masturbation in marital and sexual satisfaction: A comparative study of female masturbators and nonmasturbators. J. Sex Educ. Ther. 1991, 17, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevedo-Blasco, R. Guía Aplicada Sobre Cómo Buscar Información en Investigación. Herramientas y Aspectos Básicos. Independently Published. 2022. Available online: https://www.amazon.es/aplicada-informaci%C3%B3n-investigaci%C3%B3n-Herramientas-aspectos/dp/B0BQ99KJ89 (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fariña, F.; Arce, R.; Novo, M. Anchorage in judicial decision making. Psicothema 2002, 14, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Toro, V.; Guillén-Riquelme, A.; Quevedo-Blasco, R. Child abuse and mental disorders in juvenile delinquents: A systematic review. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2019, 17, 218–238. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, A.; Vázquez, M.J.; Seijo, D.; Arce, R. ¿Son los criterios de realidad válidos para clasificar y discernir entre memorias de hechos auto-experimentados y de eventos vistos en vídeo? [Are the reality criteria valid to classify and to discriminate between memories of self-experienced events and memories of video-observed events?]. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Salud 2018, 9, 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Study Quality Assessment Tools. 2013. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Van Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Strobe Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, S.K.; Lease, S.H.; Ellison, C.R. Predicting sexual satisfaction in women: Implications for counselor education and training. J. Couns. Dev. 2004, 82, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, S.; Costa, R.M. Satisfaction (sexual, life, relationship, and mental health) is associated directly with penile–vaginal intercourse, but inversely with other sexual behavior frequencies. J. Sex. Med. 2009, 6, 1947–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moncada, I.; Micheltorena, C.F.; Martínez-Sánchez, E.M.; Gutiérrez, J.R. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the life satisfaction checklist as a screening tool for erectile dysfunction. J. Sex. Med. 2008, 5, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugl-Meyer, A.R.; Melin, R.; Fugl-Meyer, K.S. Life satisfaction in 18- to 64-year-old Swedes: In relation to gender, age, partner and immigrant status. J. Rehabil. Med. 2002, 34, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darling, C.A.; Davidson, J.K., Sr. The relationship of sexual satisfaction to coital involvement: The concept of technical virginity revisited. Deviant Behav. 1987, 8, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLamater, J.; Moorman, S.M. Sexual Behavior in Later Life. J. Aging Health 2007, 19, 921–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lima, T.E.O.; Dissenha, R.P.; Skare, T.L.; Leinig, C.A.S. Masturbatory behavior and body image: A study among Brazilian women. Sex. Cult. 2022, 26, 474–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, C.H.N. Quociente Sexual Feminino: Um questionário brasileiro para avaliar a atividade sexual da mulher. Diagnóstico Trat. 2009, 14, 89–90. [Google Scholar]

- Favez, N.; Tissot, H. Attachment tendencies and sexual activities: The mediating role of representations of sex. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2017, 34, 732–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, W.E.; Fisher, T.D.; Walters, A.S. The Multidimensional Sexuality Questionnaire: An objective self-report measure of psychological tendencies associated with human sexuality. Ann. Sex Res. 1993, 6, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, N. Singles not sexually satisfied? Prevalence and predictors of sexual satisfaction in single versus partnered adults. Int. J. Sex. Health 2023, 35, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.M.; Nazroo, J.; O’Connor, D.B.; Blake, M.; Pendleton, N. Sexual health and well-being among older men and women in England: Findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2016, 45, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klapilová, K.; Brody, S.; Krejčová, L.; Husárová, B.; Binter, J. Sexual satisfaction, sexual compatibility, and relationship adjustment in couples: The role of sexual behaviors, orgasm, and men’s discernment of women’s intercourse orgasm. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvalem, I.L.; Træen, B.; Markovic, A.; von Soest, T. Body image development and sexual satisfaction: A prospective study from adolescence to adulthood. J. Sex Res. 2019, 56, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, K.R.; Ploubidis, G.B.; Datta, J.; Wellings, K. The Natsal-SF: A validated measure of sexual function for use in community surveys. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 27, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, D.B.; Corona, G.; Forti, G.; Tajar, A.; Lee, D.M.; Finn, J.D.; Bartfai, G.; Boonen, S.; Casanueva, F.F.; Giwercman, A.; et al. Assessment of sexual health in aging men in Europe: Development and validation of the European Male Ageing Study sexual function questionnaire. J. Sex. Med. 2008, 5, 1374–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, L.J.; Laumann, E.O.; Das, A.; Schumm, L.P. Sexuality: Measures of partnerships, practices, attitudes, and problems in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2009, 64, i56–i66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.J.; McBain, K.A.; Li, W.W.; Raggatt, P.T. Pornography, preference for porn-like sex, masturbation, and men’s sexual and relationship satisfaction. Pers. Relat. 2019, 26, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrance, K.; Byers, E.S. Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire. In Sexuality Related Measures: A Compendium, 2nd ed.; Davis, C.M., Yarber, W.L., Baureman, R., Schreer, D., Davis, S.L., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 514–519. [Google Scholar]

- Neto, R.P.; Nascimento, B.C.G.; Carvalho Dos Anjos Silva, G.; Barbosa, J.A.B.A.; Júnior, J.B.; Teixeira, T.A.; Srougi, M.; Nahas, W.C.; Hallak, J.; Cury, J. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on the sexual function of health professionals from an epicenter in Brazil. Sex. Med. 2021, 9, 100408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, C.H.N. The male sexual quotient: A brief, self-administered questionnaire to assess male sexual satisfaction. J. Sex. Med. 2007, 4, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; MacDonald, G. Single and partnered individuals’ sexual satisfaction as a function of sexual desire and activities: Results using a sexual satisfaction scale demonstrating measurement invariance across partnership status. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2022, 51, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, F.; da Conceicao Pinto, M. The satisfaction with sex life across the adult life span. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 114, 767–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, W.; Blekesaune, M. Sexual satisfaction in young adulthood: Cohabitation, committed dating or unattached life? Acta Sociol. 2003, 46, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, L.R. The Derogatis interview for sexual functioning (DISF/DISF-SR): An introductory report. J. Sex Marital Ther. 1997, 23, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, A.H.; McGarvey, E.L.; Clavet, G.J. The Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (CSFQ): Development, reliability, and validity. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1997, 33, 731–745. [Google Scholar]

- Phuah, L.A.; Teng, J.H.J.; Goh, P.H. Masturbation among Malaysian young adults: Associated sexual and psychological well-being outcomes. Sex. Cult. 2023. advanced online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, R.; Brown, C.; Heiman, J.; Leiblum, S.; Meston, C.; Shabsigh, R.; Ferguson, D.; D’Agostino, R. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2000, 26, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, D.L.; Castleman, J.M.; Bacys, K.R.; Csonka, B.; Hevesi, K. Do pornography use and masturbation play a role in erectile dysfunction and relationship satisfaction in men? Int. J. Impot. Res. 2023, 35, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, P.; Brody, S. Sexual behavior predictors of satisfaction in a Chinese sample. J. Sex. Med. 2011, 8, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillancourt-Morel, M.P.; Rosen, N.O.; Štulhofer, A.; Bosisio, M.; Bergeron, S. Pornography use and sexual health among same-sex and mixed-sex couples: An event-level dyadic analysis. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2021, 50, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrance, K.A.; Byers, E.S.; Cohen, J.N. Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire. In Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures, 4th ed.; Milhausen, R.R., Sakaluk, J.K., Fisher, T.D., Davis, C.M., Yarber, W.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 497–502. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Heath, M.A.; Tanaka, S.K.; Tanaka, H. Sexual function, behavior, and satisfaction in masters athletes. Int. J. Sex. Health 2023, 35, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, A.; Schmidt, G. Patterns of masturbatory behaviour: Changes between the sixties and the nineties. J. Psychol. Hum. Sex. 2003, 14, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhwezi, W.W.; Katahoire, A.R.; Banura, C.; Mugooda, H.; Kwesiga, D.; Bastien, S.; Klepp, K.I. Perceptions and experiences of adolescents, parents and school administrators regarding adolescent-parent communication on sexual and reproductive health issues in urban and rural Uganda. Reprod. Health 2015, 12, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushy, S.E.; Rosser, B.S.; Ross, M.W.; Lukumay, G.G.; Mgopa, L.R.; Bonilla, Z.; Massae, A.F.; Mkonyi, E.; Mwakawanga, D.L.; Mohammed, I.; et al. The management of masturbation as a sexual health issue in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: A qualitative study of health professionals’ and medical students’ perspectives. J. Sex. Med. 2021, 18, 1690–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Amaya, J.F.; Ríos-González, O. Introduction to the Special Issue: Challenges of LGBT research in the 21st century. Int. Sociol. 2019, 34, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, D.M. Social stigma and its consequences for the socially stigmatized. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2011, 5, 824–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, J.C.; Santamaría, J.; Cervilla, O.; Álvarez-Muelas, A. Masturbation in middle and late adulthood: Its relationship to orgasm. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2023, 35, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randolph, J.F., Jr.; Zheng, H.; Avis, N.E.; Greendale, G.A.; Harlow, S.D. Masturbation frequency and sexual function domains are associated with serum reproductive hormone levels across the menopausal transition. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perelman, M.A. Masturbation is a key variable in the treatment of retarded ejaculation by health care practitioners. J. Sex. Med. 2006, 3, 51–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mark, K.P.; Herbenick, D.; Fortenberry, J.D.; Sanders, S.; Reece, M. A psychometric comparison of three scales and a single-item measure to assess sexual satisfaction. J. Sex Res. 2014, 51, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E. Summated Rating Scale Construction: An Introduction; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Muñiz, J.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E. Ten steps for test development. Psicothema 2019, 31, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lawrance, K.; Byers, E.S.; Cohen, J.N. Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire. In Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures, 3rd ed.; Fisher, T.D., Davis, C.M., Yarber, W.L., Davis, S.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 525–530. [Google Scholar]

- Calvillo, C.; Sánchez-Fuentes, M.M.; Parrón-Carreño, T.; Sierra, J.C. Validation of the Interpesonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire in adults with a same-sex partner. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2020, 20, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fuentes, M.M.; Santos-Iglesias, P.; Byers, E.S.; Sierra, J.C. Validation of the Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire in a Spanish sample. J. Sex Res. 2015, 52, 1028–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peck, S.R.; Shaffer, D.R.; Williamson, G.M. Sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction in dating couples: The contributions of relationship communality and favorability of sexual exchanges. J. Psychol. Hum. Sex. 2005, 16, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrance, K.; Byers, E.S. Development of the interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction in long term relationships. Can. J. Hum. Sex. 1992, 1, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoal, P.M.; Narciso, I.D.S.B.; Pereira, N.M. What is sexual satisfaction? Thematic analysis of lay people’s definitions. J. Sex Res. 2014, 51, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervilla, O.; Jiménez-Antón, E.; Álvarez-Muelas, A.; Mangas, P.; Granados, R.; Sierra, J.C. Solitary sexual desire: Its relation to subjective orgasm experience and sexual arousal in the masturbation context within a Spanish population. Healthcare 2023, 11, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaestle, C.E.; Allen, K.R. The role of masturbation in healthy sexual development: Perceptions of young adults. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2011, 40, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, C.H.; Tanton, C.; Prah, P.; Erens, B.; Sonnenberg, P.; Clifton, S.; Macdowall, W.; Lewis, R.; Field, N.; Datta, J.; et al. Changes in sexual attitudes and lifestyles in Britain through the life course and over time: Findings from the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (NATSAL). Lancet 2013, 382, 1781–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-García, L.E.; Gómez-Berrocal, C.; Sierra, J.C. Evaluating the subjective orgasm experience through sexual content, gender, and sexual orientation. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2023, 52, 1479–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, J.L.; Hyde, J.S. A meta-analytic review of research on gender differences in sexuality, 1993–2007. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbenick, D.; Reece, M.; Schick, V.; Sanders, S.A.; Dodge, B.; Fortenberry, J.D. An event-level analysis of the sexual characteristics and composition among adults ages 18 to 59: Results from a national probability sample in the United States. J. Sex. Med. 2010, 7, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsberg, S.A.; Althof, S.; Simon, J.A.; Bradford, A.; Bitzer, J.; Carvalho, J.; Flynn, K.E.; Nappi, R.E.; Reese, J.B.; Rezaee, R.L.; et al. Female sexual dysfunction—Medical and psychological treatments, committee 14. J. Sex. Med. 2017, 14, 1463–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowland, D.L.; Hevesi, K.; Conway, G.R.; Kolba, T.N. Relationship between masturbation and partnered sex in women: Does the former facilitate, inhibit, or not affect the latter? J. Sex. Med. 2020, 17, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santtila, P.; Wager, I.; Witting, K.; Harlaar, N.; Jern, P.; Johansson, A.D.A.; Varjonen, M.; Sandnabba, N.K. Discrepancies between sexual desire and sexual activity: Gender differences and associations with relationship satisfaction. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2008, 34, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervilla, O.; Vallejo-Medina, P.; Gómez-Berrocal, C.; Sierra, J.C. Development of the Spanish short version of Negative Attitudes Toward Masturbation Inventory. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2021, 21, 100222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hevesi, K.; Tamas, S.; Rowland, D.L. Why men masturbate: Reasons and correlates in men with and without sexual dysfunction. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2023, 49, 783–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcos Hidalgo, D.; Dewitte, M. Individual, relational, and sociocultural determinants of sexual function and sexual satisfaction in Ecuador. Sex. Med. 2021, 9, 100307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos-Romero, A.I.; Sierra, J.C. Factors associated with subjective orgasm experience in heterosexual relationships. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2020, 46, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangas, P.; Granados, R.; Cervilla, O.; Sierra, J.C. Validation of the Orgasm Rating Scale in context of sexual relationships of gay and lesbian adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vowels, L.M.; Vowels, M.J.; Mark, K.P. Identifying the strongest self-report predictors of sexual satisfaction using machine learning. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2022, 39, 1191–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, C.P. Women’s masturbation: Experiences of sexual empowerment in a primarily sex-positive sample. Psychol. Women Q. 2014, 38, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foust, M.D.; Komolova, M.; Malinowska, P.; Kyono, Y. Sexual subjectivity in solo and partnered masturbation experiences among emerging adult women. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2022, 51, 3889–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).