Setting Up a Just and Fair ICU Triage Process during a Pandemic: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

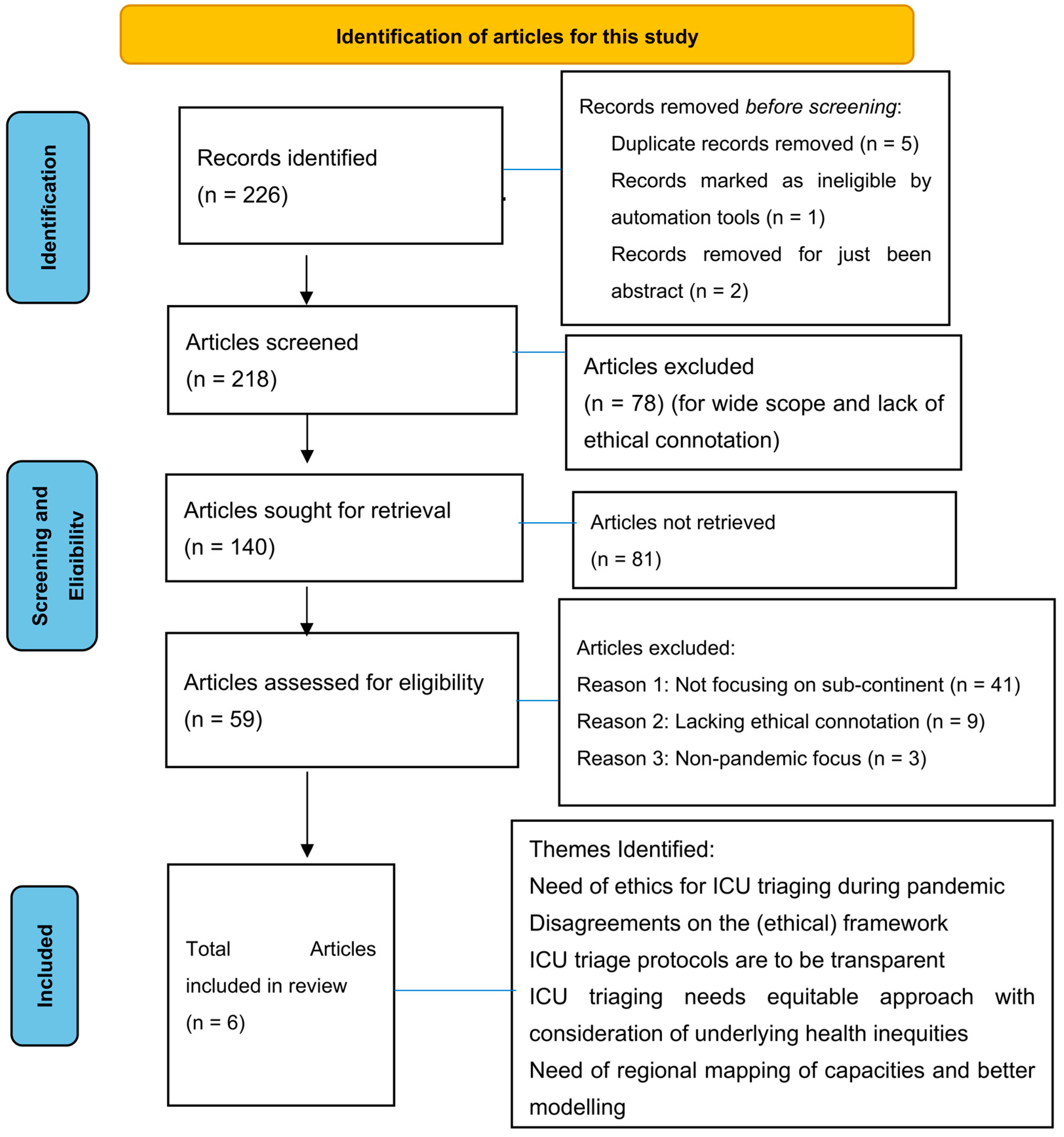

2. Methodology and Protocol

3. Data Abstraction and Synthesis

4. Critical Appraisal

5. Findings

5.1. Theme 1: Need of Ethics for ICU Triaging during Pandemics

5.2. Theme 2: Disagreements on the (Ethical) Framework

5.3. Theme 3: ICU Triage Protocols Are to Be Transparent

5.4. Theme 4: ICU Triaging Needs Equitable Approach with Consideration of Underlying Health Inequities

5.5. Theme 5: Need of Regional Mapping of Capacities and Better Modelling

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author(s) | Title | Reference | Reason for Exclusion | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ballantyne et al., 2020 [35] | Revisiting the equity debate in COVID-19: ICU is no panacea | No specific | Generic article | Did not focus on South Asia |

| Tyrrell et al., 2020 [17] | Managing intensive care admissions when there are not enough beds during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review | One South Asian country and others | Only South Asian country focused on is Sri Lanka | No comparison with other South Asian countries provided |

| White and Lo, 2021 [8] | Mitigating Inequities and Saving Lives with ICU Triage during the COVID-19 Pandemic | No specific | Generic article | Did not focus on South Asia |

| Rasita et.al., 2021 [36] | Ethics of ICU triage during COVID-19 | No specific | Generic article | Did not focus on South Asia |

Appendix B

| Ethical Value Term and Expression |

|---|

| Accountability/Accountable |

| Autonomy |

| Collaboration |

| Communication |

| Competence |

| Confidentiality |

| Consent |

| Disparity |

| Diversity |

| Duty |

| Ethic/s |

| (a) Equality, (b) Egalitarian |

| (a) Equity, (b) Equitable |

| Fair/Fairness |

| Freedom |

| Justice (a) Global; (b) Social |

| Human Rights |

| Inclusiveness/Inclusive |

| Justice |

| Liberty |

| Minimizing harm |

| Moral |

| Neighbourliness |

| Non-discriminatory/ Non discrimination |

| Obligation |

| Open/Openness |

| Participation |

| Privacy |

| Proportional/ Proportionality |

| Protection |

| Reasonableness/Reasonable |

| Reciprocity |

| Representation |

| Respect |

| Responsibility/ Responsible |

| Responsive/ Responsiveness |

| Right/Rights |

| Solidarity |

| Stewardship |

| Transparency/ Transparent |

| Trust |

| Unity |

| Utilitarian |

| (a) Utility, (b) Efficiency |

Appendix C

| Ethical Terms/Expressions | Total No. of Mentions in Plan (DGHSa 2005) | Total No. of Mentions in Plan (DGHS 2009) | Samples of Supporting Quotations in Plan (DGHSa 2005) | Samples of Supporting Quotations in Plan (DGHS 2009) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaboration | 4 | 1 | “Ensure rapid virological characterization in collaboration with WHO/lead international agencies.” (pp. 18, 22, 26) “Collaborate with international agencies to determine pathogenicity to humans.” (p. 22) | “The material prepared by MOHFW in collaboration with WHO and UNICEF would be translated into vernacular languages and given to the State Governments.” (p. 26) |

| Communication • Risk • Outbreak/evolution of pandemic • About vaccine • About the nature of restrictions | 8 | 26 | Some selected examples: “Establish effective communication with community, health care providers and the media.” (p. 6) “Establish an effective channel of communication with key response stake holders in government, non-Govt. Public and Media.” (p. 11) “Communication–To achieve public acceptance of the event.” (p. 33) | Some selected examples: “Risk Communication would be the most important non-pharmaceutical intervention.” (p. 12) Risk Communication “Public would be made aware of the need to self-quarantine through well managed risk communication strategy using print and visual media.” (p. 23) “…the objective of the communication would be to create wide scale public awareness and sensitize communities to appropriate behaviours before pandemic.” (p. 26) “…interpersonal communication training module and aids on pandemic influenza will be developed for all grass root health workers with partners/UNICEF/WHO” (p. 27) |

| Minimizing harm/risk/negative impact/social disruption/economic impact | 2 | 2 | “To minimize the risk of human infection from contact with infected animals.” (p. 14) “To minimize the risk of human infection from contact with infected animals.” (p. 15) | “All technical procedures should be performed in a way that minimizes the formation of aerosols and droplets.” (p. 110) “Early implementation of infection control precautions to minimize nosocomial/household spread of disease.” (p. 118) |

| Representation | 1 | - | “Include new institutions in the network to have representation of all zones.” (p. 9) | |

| Trust | - | 1 | - | “This will help in building public trust…” (p. 27) |

Appendix D

| Sl. No. | Ethical Term/Expression | Nepal Plan (August 2007–November 2010) | Bangladesh Plan (2006–2008) | Bangladesh Plan (2009–2011) | Sri Lanka Plan (2005) | Sri Lanka Plan (2006) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Accountability | 1 “…ensuring a two-way flow of information and accountability.” (p. 46) | - | - | - | |

| 2. | Collaboration | 3 Some selected examples The DLSO will in collaboration with the District Local Development Office, train in one day workshops. (p. 14) “…with collaboration from regional, district and local level sub-committees.” (p. 53) | 18 One selected example “So multi-sectoral collaboration and coordination are of paramount importance…” (p. 24) | 8 One selected example “Ensure essential services; and to strengthen bilateral, regional and international collaboration.” (p. 1) | 14 One selected example “…all organisations including the government, private sector and community require close collaboration and synergy.” (p. 7) | 3 One selected example “…in collaboration with the Estate Infrastructure and Livestock Department.” (p. 1) |

| 3 | Communication | 127 Some selected examples “…improving the capacity for risk communication.” (p. 47) The Plan proposes a national communication strategy… (p. 47) The failure of a communication response in Nepal during a pandemic could result in major panic (p. 48) | 39 One selected example “To establish and ensure an integrated communication strategy responsive to public concerns.” (p. 28) | 72 Some selected examples “Official communication during outbreak, response and control activities” (p. 3) “Scientific communication among scientists and officials through training, workshop and meeting” (p. 3) | 26 Some selected examples “…risk communication are critical steps of preparedness.” (p. 3) “Establish communication networking among all stakeholders.” (p. 36) | 1 “Risk Communication– Communication Strategic Plan was developed by the UNICEF in collaboration with the Epidemiology Unit, Health Education Bureau and other stakeholders” (p. 3) |

| 4 | Ethic/s | 1 “…abide by the national and international accepted ethical standards.” (p. 33) | - | - | - | - |

| 5. | Equity | 1 “…they are within an equity and human rights perspective…” (p. 33) | - | - | - | - |

| 6 | Fair/Fairness | 2 “If the backyard poultry farmers are paid a fair compensation to cover the value of the birds destroyed,” (p. 17) “…Rs.100 per bird and for all birds culled from his flock, is a fair rate of compensation.” (p. 17) | - | - | - | - |

| 7 | Human Rights | 1 “…they are within an equity and human rights perspective…” (p. 33) | - | - | - | - |

| 8. | Minimizing harm/risk/negative impact/social disruption/economic impact | 4 “…minimize public fear and facilitate public protection…” (p. 16) “The plan is developed to minimize the risks…” (p. 48) “…minimize the social disruption…” (p. 52) | 7 Some selected examples “…to minimize the risk of human pandemic influenza.” (pp. 6, 25) “…minimize the negative socio- economic impact…” (p. 25) “…minimize social disruption and economic burden.” (p. 26) | 8 Some selected examples “…to minimize socio-economic and environmental impact.” (pp. 1, 43) “…minimize negative socioeconomic and environmental impact during pandemic” (p. 33) “…to minimize concern, social disruption, and stigmatization and correct misinformation.” (p. 61) | 2 One selected example “To reduce the impact of the pandemic virus on morbidity and mortality and minimize social disruption minimize social disruption” (p. 16) | |

| 9 | Moral | 1 “…bring in an element of moral hazard in compensation payments to organized poultry farms.” (p. 18) | - | - | - | - |

| 10 | Participation | 11 Some selected examples “…with the participation of the Regional Directorates of Livestock Services and Regional Health Directorates and other governmental and non-governmental concerned organizations.” (pp. 4, 5) | 1 “…with participation from relevant government, NGOs, private sectors…” (p. 25) | 5 One selected example “…multi-sectoral approach with community participation and collaboration with International organizations.” (p. 1) | 4 One selected example “Full mobilization of health services and strict enforcement of epidemic law during pandemic will only be successful on the basis of full participation of decentralized levels.” (pp. 21, 23) | |

| 11 | Protection | - | 8 Some selected examples “…protection of healthcare workers and other vulnerable groups.” (p. 8) “…the protection and conservation of wildlife.” (p. 12) | 6 One selected example “Strengthening safe clinical care with protection of health Personnel” (p. 45) | 5 “This includes specific approaches…including protection of cullers and health care workers.” (p. 4) | |

| 12 | Reasonable/ Reasonableness | 1 Reasonable care necessary (p. 172) | - | - | - | |

| 13 | Responsibility/Responsible/ | 38 Some selected examples “…ensuring responsible outbreak studying to avoid panic…” (p. 1) “…responsible media studying on avian influenza.” (p. 53) | 2/27 One selected example “…pandemic preparedness is the responsibility of all…” (p. 6) | 59 One selected example “The Forest Department (FD) is responsible for all activities concerning wildlife” (p. 16) | 5 Some selected examples “Pandemic preparedness is the responsibility of all…” (p. 7) “…some agencies will bear the primary responsibility while the others will also be active…” (p. 15) | |

| 14 | Responsive/Responsiveness | - | 1 “To establish and ensure an integrated communication strategy responsive to public concerns.” (p. 28) | - | 1 “To establish and ensure an integrated communication strategy responsive to public concerns.” (p. 17) | |

| 15 | Right/Rights | 1 “The constitution of the Peoples Republic of Bangladesh assures “health is the basic right of every citizen of the republic”.” (p. 26) | 1 “The constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh assures “health is the basic right of every citizen of the republic”.” (p. 37) | - | ||

| 16 | Transparency/ Transparent | 4 One selected example “…transparent and proactive public information strategy related to avian influenza and other epidemics.” (p. 53) | 1 “Transparency is a key strategy to gain the public’s trust in the government and other stakeholders and is critical to disaster management.” (p. 8) | - | 1 “Transparency is a key strategy to gain public trust in the government which is critical to disaster management.” (p. 4) | |

| 17 | Trust | 5 Some selective examples “…communication failure by governmental officials could create panic among the public: undermine public trust/confidence…” (p. 16) “…maintain and restore trust.” (p. 49) | 1 “Transparency is a key strategy to gain the public’s trust in the government and other stakeholders and is critical to disaster management.” (p. 8) | - | 1 “Transparency is a key strategy to gain public trust in the government which is critical to disaster management.” (p. 4) |

Appendix E

| Sl. No. | Ethical Term/ Expression | Nepal (2021) | Bangladesh | Sri Lanka (2020) | India (2020) | Pakistan (2020) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Accountability | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | Collaboration/collaborative | 6 One selected example “The plan envisioned collaborations between the public, non-governmental, and private sectors, as well as…” (p. 28) | - | 2 An example “In collaboration with Ceylon College of Physicians” | - | 3 One example “These decisions should therefore not be made alone but through a collaborative process which will help to share and lessen the burden.” (p. 6) |

| 3 | Communication | 53 One selected example “The communication targets were set according to the socio-ecological model and epidemiology of the disease. It was also important for the messaging mechanisms to reach as wide an audience as possible” (p. 42) | 1 “Communicate clearly: simple instructions; closed-loop communication (repeat instructions back); adequate volume without shouting” (p. 49) | 5 Selected example “Availability of a dedicated smart phone and intercom facilities in cohort or triage ICU is important to improve communication and to prevent frequent staff movements.” | 14 One example “Extensive inter-personal and community-based communication.” (p. 10) | 3 “Compassionate, honest and direct communication with patients or surrogates is important beginning from the time of admission to the hospital.” (p. 6) |

| 4 | Equity | 1 “The measures put in place as part of the COVID-19 response also took into consideration gender, equity, and human rights” (p. 44) | - | - | - | |

| 5 | Ethic/s | 5 One selected sample “Perceptions on Ethics of Public Health Interventions during the COVID-19 Outbreak” (p. 79) | - | - | 29 One example “COVID-19 pandemic poses a catastrophic health emergency which necessitates prudent use of scarce resources while safeguarding ethical values and professional virtues that form the core of humanistic health care for patients.” (p. 4) | |

| 6 | Fair/Fairness | - | - | - | - | |

| 7 | Human Rights | 1 “The measures put in place as part of the COVID-19 response also took into consideration gender, equity, and human rights” (p. 44) | - | - | ||

| 8 | Minimising harm/risk/negative impact/social disruption/economic impact | 1 “Minimising the risk of transmission from the infected or suspected.” (p. 27) | - | 11 Selected example “Areas separated from the rest of the ICU beds to minimize risk of in-hospital transmission” (p. 14) | 1 “…is to provide an ethical framework for institutions to formulate Standard Operating Procedures for making healthcare decisions that will maximize benefits to the public while minimizing risks to healthcare providers” (p. 3) | |

| 9 | Moral | 2 “The Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) provided NARTC with PPE sets, which included gowns, boots and masks, among others, for their frontline workers which was a huge boost to morale.” (p. 14) | - | 1 “Allocation of limited resources can be morally distressing and emotionally draining for clinicians.” (p. 6) | ||

| 10 | Participation | 1 “The new laboratory network was facilitated by the federal MoHP with the active participation and contribution of provincial and local governments and the private sector.” (p. 63) | - | |||

| 11 | Protection/Protect | 20 One selected example “When the next pandemic strikes, the whole world needs to implement best practices to save lives and protect livelihoods.” (p. 89) | 8 One example “Protecting healthcare providers is the first priority, as you are the primary line of defense for this patient, and upcoming patients.” (p. 48) | 7 “Lung protective ventilator strategy remains the mainstay of delivering ventilator therapy.” (p. 18) | 8 One example “Buffer stock of personal protective equipment maintained.” (p. 4) | 5 One example “Dire circumstances of the pandemic necessitate shifting to a public health approach that requires distribution of scarce resources for the benefit and protection of the larger society often times at the expense of benefits to individual patients.” (p. 4) |

| 12 | Reasonable/ Reasonableness | - | 4 One example “In medical wards not equipped with negative pressure rooms, like those which admit most COVID-19 patients because of reduced bed availability, it is reasonable to imagine a higher exhaled air dispersion and contamination.” (p. 29) | - | - | |

| 13 | Representation/represent | 17 One example “On January 26, 2020, Patan Hospital held a multispecialty meeting and formed a task force that consisted of representatives from various departments, each having specific roles and responsibilities.” (p. 12) | 2 One example “Multi-disciplinary expert team composed of consultant microbiologist/Physician or any representative from the clinical team; e.g., Respiratory Physician, Intensivist, Virologist based on the availability (for overall technical guidance)” (p. 30) | 1 “At the Central level, only Secretary (H) or representative nominated by her shall address the media” (p. 20) | - | |

| 14 | Responsibility/Responsible | 3 One example “The Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) is the national autonomous apical body responsible for conducting and supporting health research with the highest level of ethical standards within the Republic of Nepal.” (p. 75) | 1 “The referring team shall maintain primary responsibility for the patient with a multidisciplinary team approach to patient management.” (p. 56) | 1 One example “The referring team shall maintain responsibility for the patient up to admission to ICU, and shall remain responsible for ongoing management if admission is refused or deferred.” (p. 13) | 2 One example “Under which data managers (deployed from IDSP/NHM) responsible for collecting, collating and analysing data from field and health facilities.” (p. 21) | 2 One example “It is the responsibility of institutions and government to ensure the availability of compassionate end of life care and appropriate personnel.” (p. 5) |

| 15 | Responsive/Responsiveness | - | - | - | - | |

| 16 | Right/Rights | 6 “The measures put in place as part of the COVID-19 response also took into consideration gender, equity, and human rights” (p. 44) | - | - | - | |

| 17 | Transparency | 2 One example “Consistency and transparency are vital in information sharing.” (p. 88) | - | - | 1 “This may be through use of institutional notice boards or websites to ensure public awareness and transparency” (p. 4) | |

| 18 | Trust | 7 One example “To engage the public and increase compliance, respected personalities should be brought in to build community trust.” (p. 23) | - | - | 2 One example “Trust is the core of ethical physician–patient relationships.” (p. 6) |

References

- Chakraborty, R. Ethics in Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Plan: A Perspective from Social Justice. Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, 2015. Available online: http://www.idr.iitkgp.ac.in/xmlui/handle/123456789/5051 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). Ethical and Legal Considerations in Mitigating Pandemic Disease: Workshop Summary. Forum on Microbial Threats. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). 2007. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK54169/ (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Ethical Considerations in Developing a Public Health Response to Pandemic Influenza; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; Available online: www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/ (accessed on 9 December 2009).

- Tognotti, E. Lessons from the history of quarantine, from plague to influenza A. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborti, C.; Chakraborty, R. Ethical Language Usage in Pandemic Plans: A Study on Pandemic Plans of Some South Asian Countries. Eubios J. Asian Int. Bioeth. 2011, 21, 118–129. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanbari, V.; Ardalan, A.; Zareiyan, A.; Nejati, A.; Hanfling, D.; Bagheri, A. Ethical prioritization of patients during disaster triage: A systematic review of current evidence. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2019, 43, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eubios Ethics Institute. World Emergency COVID19 Pandemic Ethics (We Cope) Committee. Statement on Ethical Triage Guidelines for COVID-19. Available at Microsoft Word—WECOPETriage Statement for COVID draft 2_Anke.docx. 2020. Available online: https://www.eubios.info/assets/docs/WECOPETriage_Statement_for_COVID.151172039.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- White, D.B.; Lo, B. Mitigating Inequities and Saving Lives with ICU Triage during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 203, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). Clinical Guidance for Management of Adult COVID-19 Patients; AIIMS/ICMR-COVID-19 National Task Force/Joint Monitoring Group (Dte.GHS), Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2022.

- Ministry of Health (MOH). Provisional Clinical Practice Guidelines on COVID-19 Suspected and Confirmed Patients; MOH: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2020.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW). Updated Containment Plan for Large Outbreaks Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19); Version 3 16th May 2020; MOHFW, Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2020.

- Ministry of National Health Services, Regulations, and Coordination (MNHSRC). Guidelines Clinical Management Guidelines for COVID-19 Infections; Government of Pakistan: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2020.

- Nuffield Council on Bioethics (NCB). Policy Briefing. Key Challenges for Fair and Equitable Access to COVID 19 Vaccines and Treatments. The Nuffield Council on Bioethics, 2020. Available online: https://www.nuffieldbioethics.org (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Nuffield Trust. Health System Recovery from COVID-19 International Lessons for the NHS; Nuffield Trust: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron, K.; Abdi, S.; De Corby, K.; Mensah, G.; Rempel, B.; Manson, H. Theories, models and frameworks used in capacity building interventions relevant to public health: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochrane. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Cochrane Training. 2019. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Tyrrell, C.S.B.; Mytton, O.T.; Gentry, S.V.; Thomas-Meyer, M.; Allen, J.L.Y.; Narula, A.A.; McGrath, B.; Lupton, M. Managing intensive care admissions when there are not enough beds during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Thorax 2021, 76, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwers, M.C.; Kho, M.E.; Browman, G.P.; Burgers, J.S.; Cluzeau, F.; Feder, G.; Fervers, B.; Graham, I.D.; Grimshaw, J.; Hanna, S.E.; et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 2010, 182, E839–E842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, T.; Gupta, K.; Dyer, C.; Fackrell, R.; Wexler, S.; Boyes, H.; Colleypriest, B.; Graham, R.; Meehan, H.; Merritt, S. Development of a structured process for fair allocation of critical care resources in the setting of insufficient capacity: A discussion paper. J. Med. Ethics 2020, 47, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, Y.; Chaudhry, D.; Abraham, O.C.; Chacko, J.; Divatia, J.; Jagiasi, B.; Kar, A.; Khilnani, G.C.; Krishna, B. Critical Care for COVID-19 Affected Patients: Position Statement of the Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 24, 222–241. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, V.; Padhy, S.K. Ethical dilemmas faced by health care workers during COVID-19 pandemic: Issues, implications and suggestions. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bioethics Committee (NBC). COVID-19 Pandemic: Guidelines for Ethical Healthcare Decision-Making in Pakistan; Ministry of National Health Services Regulations & Coordination (MONHSRC), NBC: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2020.

- Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP). Responding to COVID-19: Health Sector Preparedness, Response and Lessons Learnt; Ministry of Health and Population: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2021.

- Bhuiyan, A. Seeking an ethical theory for the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak with special reference to Bangladesh’s law and policy. Dev. World Bioeth. 2020, 21, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khursheed, M.; Fayyaz, J.; Jamil, A. Setting up triage services in the emergency department: Experience from a tertiary care institute of Pakistan. A journey toward excellence. J. Ayub Med. Coll. 2015, 27, 737–740. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.; Garg, R.; Chakra Rao, S.S.; Ahmed, S.M.; Divatia, J.V.; Ramakrishnan, T.V.; Mehdiratta, L.; Joshi, M.; Malhotra, N. Indian Resuscitation Council (IRC) suggested guidelines for Comprehensive Cardiopulmonary Life Support (CCLS) for suspected or confirmed coronavirus disease (COVID-19) patient. Indian J. Anaesth. 2020, 64, S91–S96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Supady, A.; Randall Curtis, J.; Abrams, D.; Lorusso, R.; Bein, T.; Boldt, J.; Brown, C.E.; Duerschmied, D.; Metaxa, V. Allocating scarce intensive care resources during the COVID-19 pandemic: Practical challenges to theoretical frameworks. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svantesson, M.; Griffiths, F.; White, C.; Bassford, C.; Slowther, A. Ethical conflicts during the process of deciding about ICU admission: An empirically driven ethical analysis. J. Med. Ethics 2021, 47, e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, G.S.; Lamsal, R.; Tiwari, P.; Acharya, S.P. Anesthesiology and Critical Care Response to COVID-19 in Resource-Limited Settings: Experiences from Nepal. Anesthesiol. Clin. 2021, 39, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Nundy, S. Rationing medical resources fairly during the Covid 19 crisis: Is this possible in India (or)America? Curr. Med. Res. Pract. 2021, 10, 127–129. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh (GOPRB). National Guideline on ICU Management of Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients; Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, GOPRB: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2020.

- Gopichandran, V. Clinical ethics during the COVID-19 pandemic: Missing the trees for the forest. Indian J. Med. Ethics 2020, 5, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, S.; Leligdowicz, A.; Adhikari, N.K.J. Intensive Care Unit Capacity in Low-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phua, J.; Weng, L.; Ling, L.; Egi, M.; Lim, C.M.; Divatia, J.V.; Shrestha, B.R.; Arabi, Y.M.; Ng, J. Intensive care management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Challenges and recommendations. Lancet Respir. 2020, 8, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, A.; Rogers, W.A.; Entwistle, V.; Towns, C. Revisiting the equity debate in COVID-19: ICU is no panacea. J. Med. Ethics 2020, 46, 641–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasita, V.; Baumann, H.; Biller-Andorno, N. Ethics of ICU triage during COVID-19. Br. Med. Bull. 2021, 138, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Initial Hits | Results after Initial Screen | Key Words Used to Search Relevant Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed/MEDLINE | 10 | 7 | “COVID 19”; OR “Critical Care”; OR “Ethics”; OR “ICU”; OR “Pandemic”; OR “Prioritisation”; OR “Rationing”; OR “Social Justice”; OR “Sub-Continent”; OR “Triage” AND year_ cluster: (“2021” OR “2020” OR “2022” OR “2019”) AND (year_ cluster: (2015 TO 2022) |

| COCHRANE | 9 | 6 | |

| WHO | 5 | 2 | |

| King’s Fund | 6 | 0 | |

| NHS | 6 | 1 | |

| DOH | 3 | 2 | |

| Nuffield Council on Bioethics | 3 | 3 | |

| EPPI-Centre | 2 | 1 | |

| Centre for Reviews and Dissemination | 1 | 0 | |

| BMA | 10 | 3 | |

| NICE | 2 | 2 | |

| Intensive Care Society | 16 | 13 | |

| ProQuest | 15 | 15 | |

| SCOPUS | 6 | 6 | |

| EUBIOS Ethics Institute | 2 | 2 | |

| Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India | 73 | 48 | |

| Ministry of Health and Population, Nepal | 6 | 3 | |

| Ministry of Health, Bhutan | N/A | N/A | |

| Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Bangladesh | 14 | 3 | |

| Ministry of Health, Sri Lanka | 14 | 12 | |

| Ministry of National Health Services Regulations and Coordination, Government of Pakistan | 17 | 14 | |

| Total | 226 | 140 | |

| Total following removal of duplicates and application of inclusion/exclusion criteria | 59 | 40 |

| Reference Location | Need of Ethics | Ethical Framework (Explicit/Implicit) | Open and Transparent Protocol for ICU | ICU Triaging Needs Equitable Approach | Suitability of Existing Rationing Strategy for Pandemic ICU Triage | Need of Regional Mapping of Capacities | Need of Better Modelling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Nepal | Yes | Yes/Implicit | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Pakistan | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Bangladesh | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Sri Lanka | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| References | Scope and Purpose Stated for ICU | Stakeholder Involvement Stated | Rigour of Development | Clarity of Presentation | Applicability | Editorial Independence | Appraiser Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | Yes | Not explicitly | Containment Plan by Govt. | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5 |

| Nepal | Yes | Yes | Lessons Learned by Govt. | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Pakistan | Yes | Yes | National Bioethics Commission | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Bangladesh | Yes | Not explicitly | Guideline by Govt. | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5 |

| Sri Lanka | Yes | Not explicitly | Guideline by Govt. | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chakraborty, R.; Achour, N. Setting Up a Just and Fair ICU Triage Process during a Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020146

Chakraborty R, Achour N. Setting Up a Just and Fair ICU Triage Process during a Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2024; 12(2):146. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020146

Chicago/Turabian StyleChakraborty, Rhyddhi, and Nebil Achour. 2024. "Setting Up a Just and Fair ICU Triage Process during a Pandemic: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 12, no. 2: 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020146

APA StyleChakraborty, R., & Achour, N. (2024). Setting Up a Just and Fair ICU Triage Process during a Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 12(2), 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020146