Population Distribution and Patients’ Awareness of Food Impaction: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

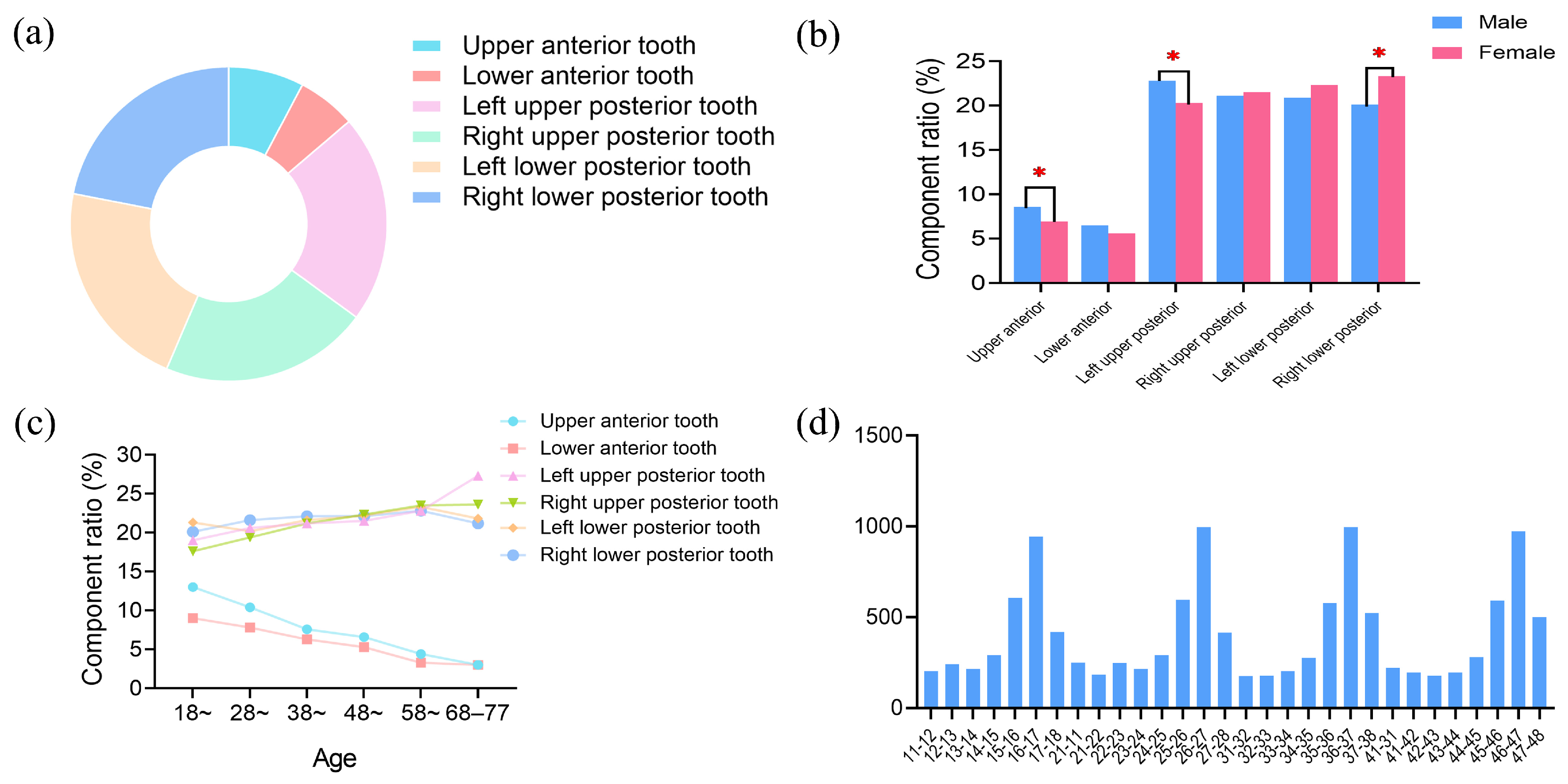

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Influencing Factors on the Prevalence of Food Impaction

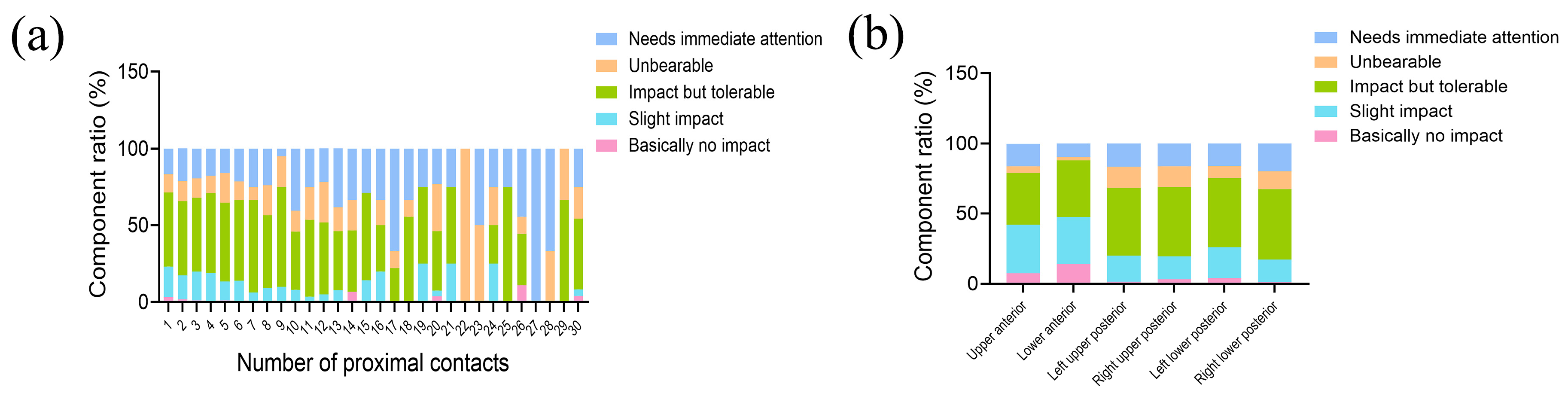

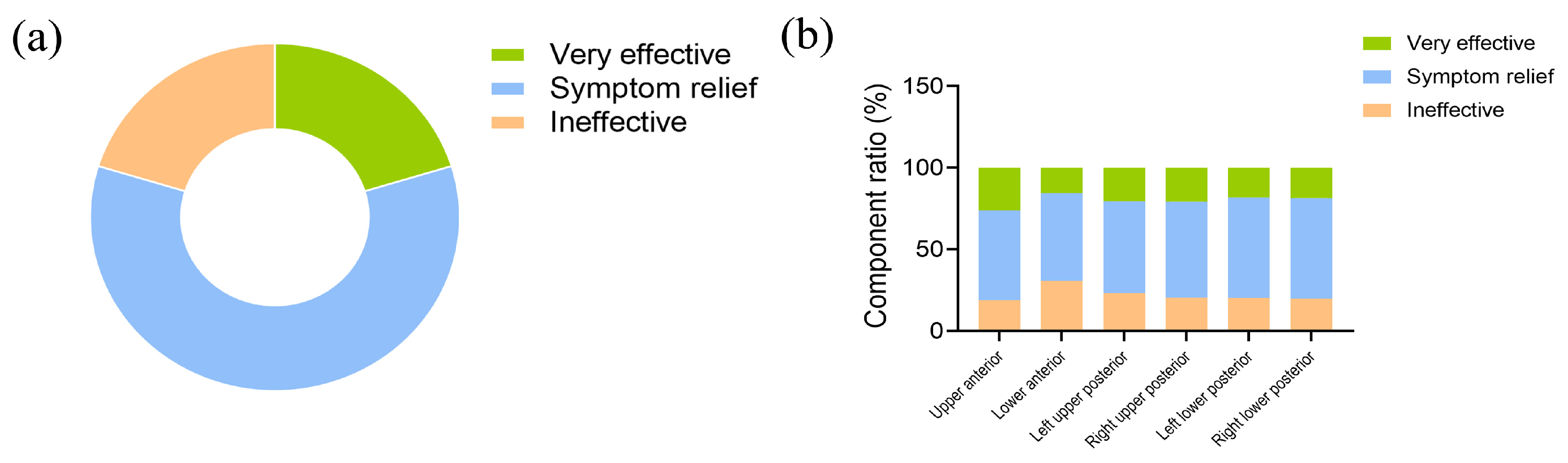

3.3. Patients’ Awareness and Coping Attitudes towards Food Impaction

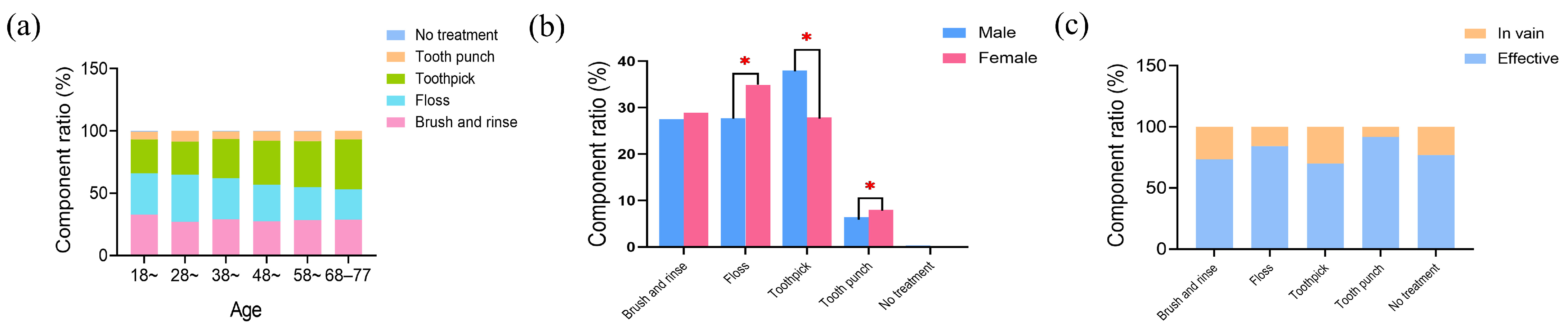

3.4. Oral Cleaning Methods for Food Impaction Patients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chanthasan, S.; Mattheos, N.; Pisarnturakit, P.P.; Pimkhaokham, A.; Subbalekha, K. Influence of interproximal peri-implant tissue and prosthesis contours on food impaction, tissue health and patients’ quality of life. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2022, 33, 768–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messer, J.G.; Jiron, J.M.; Chen, H.-Y.; Castillo, E.J.; Calle, J.L.M.; Reinhard, M.K.; Kimmel, D.B.; Aguirre, J.I. Prevalence of food impaction-induced periodontitis in conventionally housed marsh rice rats (Oryzomys palustris). Comp. Med. 2017, 67, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Radafshar, G.; Khaghani, F.; Rahimpoor, S.; Shad, A. Long-term stability of retreated defective restorations in patients with vertical food impaction. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2020, 24, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Sakagami, R.; Ozaki, M.; Taniguchi, K. The effect of insulin administration and antibacterial irrigation with chlorhexidine gluconate on the disturbance of periodontal tissue caused by food impaction in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Hard Tissue Biol. 2015, 24, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, L.; Hughes, F.J.; Preshaw, P.M. Diabetes and periodontal disease: A two-way relationship. Br. Dent. J. 2014, 217, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.-P.; Bo, X.-W.; Dou, H.-X.; Fan, Q.; Wang, H. Association between periodontal disease and coronary heart disease: A bibliometric analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, A.; Sivaraman, K.; Narayan, A.I.; Balakrishnan, D. Etiology and classification of food impaction around implants and implant-retained prosthesis. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2019, 21, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Wang, L. The reduction of vertical food impact using adjacent surface retaining zirconium crowns preparation technique: A 1-year follow-up prospective clinical study. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, L.; Deng, C.; Zhao, B. Clinical assessment of food impaction after implant restoration: A retrospective analysis. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 41, 1056–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Guo, Y.; Jonasson, J.M. Association between social capital and oral health among adults aged 50 years and over in China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D. Oral diseases affect some 3.9 billion people. Evid.-Based Dent. 2013, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almabadi, E.S.; Bauman, A.; Akhter, R.; Gugusheff, J.; Van Buskirk, J.; Sankey, M.; Palmer, J.E.; Kavanagh, D.J.; Seymour, G.J.; Cullinan, M.P.; et al. The effect of a personalized oral health education program on periodontal health in an at-risk population: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubert-Jeannin, S.; Field, J.; Davies, J.; Manzanares, C.; Dixon, J.; Vital, S.; Paganelli, C.; Quinn, B.; Gerber, G.; Akota, I. O-Health-Edu: Advancing oral health: A vision for dental education. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, ckaa166-631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Guo, Q.; Li, Q.; Chai, R.; Wu, F. Research on the characteristics of food impaction with tight proximal contacts based on deep learning. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2021, 2021, 1000820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenstein, G.; Carpentieri, J.; Cavallaro, J. Open contacts adjacent to dental implant restorations etiology, incidence, consequences, and correction. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2016, 147, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomans, B.; Opdam, N.; Attin, T.; Bartlett, D.; Edelhoff, D.; Frankenberger, R.; Benic, G.; Ramseyer, S.; Wetselaar, P.; Sterenborg, B.; et al. Severe Tooth Wear: European Consensus Statement on Management Guidelines. J. Adhes. Dent. 2017, 19, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramoglu, S.; Tasar, S.; Gunsoy, S.; Ozan, O.; Meric, G. Tooth-implant connection: A review. ISRN Biomater. 2013, 2013, 921645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, E.; Katina, S.; Kullmer, O.; Fiorenza, L.; Benazzi, S. Quantittive assessment of interproximal wear facet outlines for the association of isolated molars. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2011, 144, 309–316. [Google Scholar]

- Sarig, R.; Lianopoulos, N.V.; Hershkovitz, I.; Vardimon, A.D. The arrangement of the interproximal interfaces in the human permanent dentition. Clin. Oral Investig. 2013, 17, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Leveille, S.G.; Shi, L. Multiple chronic diseases associated with tooth loss among the us adult population. Front. Big Data 2022, 5, 932618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hong, J.; Xiong, D.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Huang, S.; Hua, F. Are parents’ education levels associated with either their oral health knowledge or their children’s oral health behaviors? A survey of 8446 families in Wuhan. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delwel, S.; Binnekade, T.T.; Perez, R.S.G.M.; Hertogh, C.M.P.M.; Scherder, E.J.A.; Lobbezoo, F. Oral hygiene and oral health in older people with dementia: A comprehensive review with focus on oral soft tissues. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdardottir, A.S.; Geirsdottir, O.G.; Ramel, A.; Arnadottir, I.B. Cross-sectional study of oral health care service, oral health beliefs and oral health care education of caregivers in nursing homes. Geriatr. Nurs. 2022, 43, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bado, F.M.R.; Barbosa, T.d.S.; Soares, G.H.; Mialhe, F.L. Oral health literacy and periodontal disease in primary health care users. Int. Dent. J. 2022, 72, 654–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari-Moradabadi, A.; Rakhshanderou, S.; Ramezankhani, A.; Ghaffari, M. Explaining the concept of oral health literacy: Findings from an exploratory study. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2022, 50, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordass, B.; Ruge, S.; Quooss, A.; Hugger, A.; Mundt, T. Occlusion of artificial teeth in partial dentures in the “chewing center”—First exploratory population-based evaluations. Int. J. Comput. Dent. 2014, 17, 185–195. [Google Scholar]

- Messer, J.; Calle, J.M.; Jiron, J.; Castillo, E.; Van Poznak, C.; Bhattacharyya, N.; Kimmel, D.; Aguirre, J. Zoledronic acid increases the prevalence of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in a dose dependent manner in rice rats (Oryzomys palustris) with localized periodontitis. Bone 2018, 108, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozler, C.O.; Dalgara, T.; Sahne, B.S.; Yegenoglu, S.; Turgut, M.D.; Baydar, T.; Tekciceka, M.U. Oral care habits, awareness and knowledge on oral health: A sample of pharmacy students. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2022, 9104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.-L.; Cao, C.Y.; Xu, Q.-J.; Xu, X.-H.; Yin, J.-L. Atraumatic restoration of vertical food impaction with an open contact using flowable composite resin aided by cerclage wire under tension. Scientifica 2016, 2016, 4127472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Gao, M.; Qi, C.; Liu, S.; Lin, Y. Drug-induced gingival hyperplasia and scaffolds: They may be valuable for horizontal food impaction. Med. Hypotheses 2010, 74, 984–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Zhong, Z.; Wu, Y.; Shu, R.; Wu, Y.; Li, C. Hyaluronic acid vs. physiological saline for enlarging deficient gingival papillae: A randomized controlled clinical trial and an in vitro study. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalz, G.; Schmidt, L.; Haak, R.; Büchi, S.; Goralski, S.; Roth, A.; Ziebolz, D. Prism (pictorial representation of illness and self-measure) as visual tool to support oral health education prior to endoprosthetic joint replacement—A novel approach in dentistry. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, V.; Hoang, H.; Crocombe, L.A.; Goldberg, L.R. Incorporating oral health care education in undergraduate nursing curricula—A systematic review. BMC Nurs. 2020, 19, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Category | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–27 | 375 (10.5%) |

| 28–37 | 790 (22.1%) | |

| 38–47 | 997 (27.8%) | |

| 48–57 | 918 (25.6%) | |

| 58–67 | 419 (11.7%) | |

| 68–78 | 82 (2.3%) | |

| Gender | male | 1486 (41.5%) |

| female | 2095 (58.5%) |

| Evaluation of the Impact of Life | N | Component Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Basically no impact | 60 | 1.9 |

| Slight impact | 504 | 16.2 |

| Impacted but tolerable | 1501 | 48.5 |

| Unbearable | 421 | 13.5 |

| Needs immediate attention | 616 | 19.8 |

| Total | 3111 | 100.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Z.; He, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, M.; Wang, F.; Chen, J. Population Distribution and Patients’ Awareness of Food Impaction: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171688

Zhao Z, He Z, Liu X, Wang Q, Zhou M, Wang F, Chen J. Population Distribution and Patients’ Awareness of Food Impaction: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2024; 12(17):1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171688

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Zhe, Zikang He, Xiang Liu, Qing Wang, Ming Zhou, Fu Wang, and Jihua Chen. 2024. "Population Distribution and Patients’ Awareness of Food Impaction: A Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 12, no. 17: 1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171688

APA StyleZhao, Z., He, Z., Liu, X., Wang, Q., Zhou, M., Wang, F., & Chen, J. (2024). Population Distribution and Patients’ Awareness of Food Impaction: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 12(17), 1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171688