Hamman’s Syndrome after Vaginal Delivery: A Case of Postpartum Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum with Subcutaneous Emphysema and Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

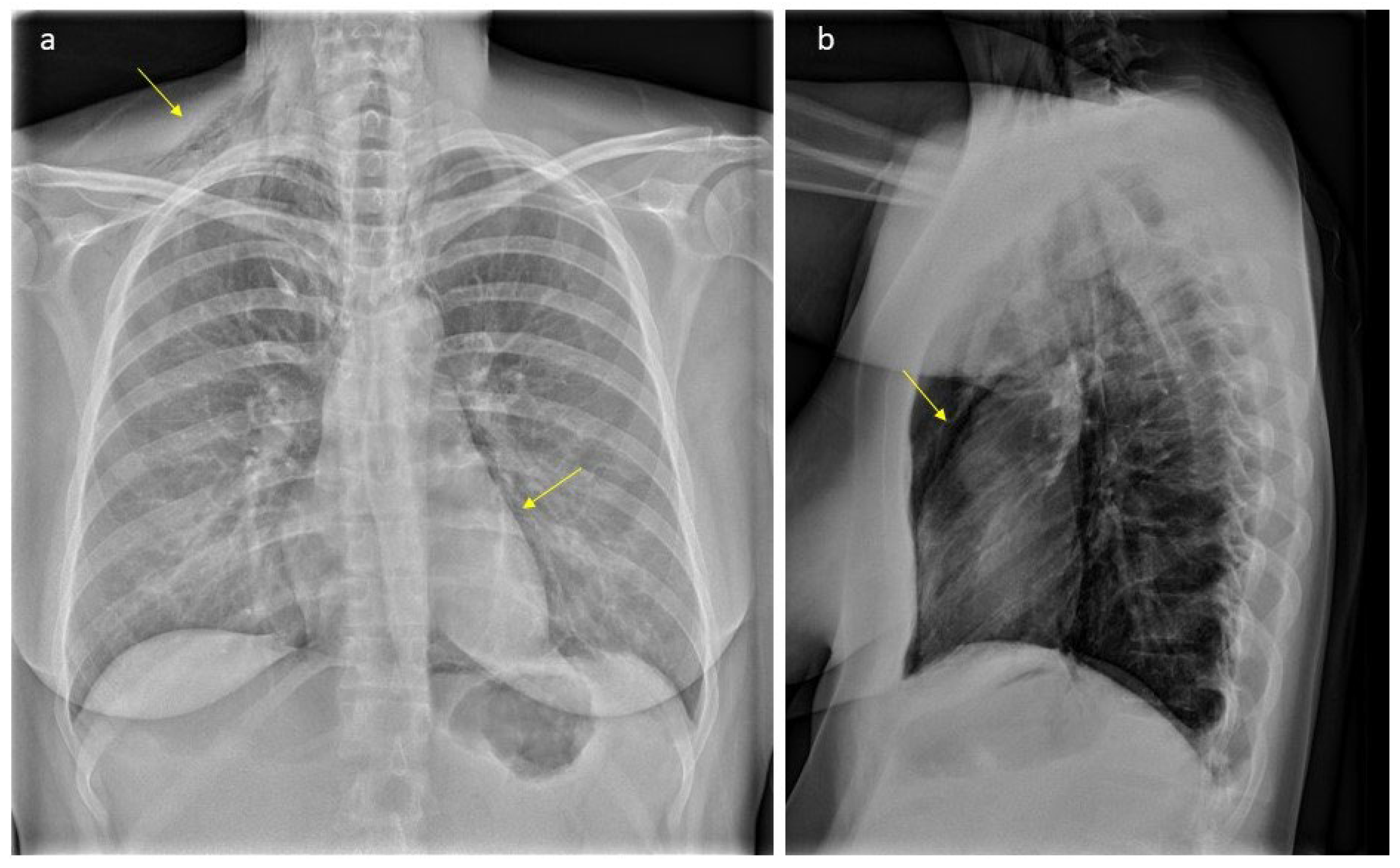

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

| Author | Age y/o | Parity | When Symptoms Developed | Duration of Labor | Week of Gestation | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sutherland et al. 2002 [24] | 32 | Para 1 | Postpartum | 8 h | N/A | None |

| Sutherland et al. 2002 [24] | 22 | Para 1 | 13 h postpartum | N/A | N/A | None |

| Miguil et al. 2004 [25] | 19 | Para 0 | N/A | N/A | 40 | Oxygen and analgesics, C-section |

| Duffy 2004 [26] | 19 | Para 0 | 2 h | 90 min 2nd stage | 40 | Oxygen v analgesics |

| Bonin et al. 2006 [27] | 27 | Para 0 | 2nd stage | 6 h | 38 | Lorazepam for anxiety and anxiolytics for dyspnea |

| Norzilawati et al. 2007 [28] | 21 | Para 0 | 12 h postpartum | 4 h, 100 min 2nd stage | 40 | None |

| Yadav et al. 2008 [29] | 21 | Para 0 | 2nd stage | 2nd stage 1.5 h | N/A | Oxygen and analgesics |

| Mahboob et al. 2008 [30] | 24 | Para 0 | 18 h postpartum | N/A Normal | 39 | Oral antibiotics, IV fluids, and analgesics |

| Zapardiel et al. 2009 [31] | 29 | Para 0 | Postpartum | N/A | 39 | Oxygen |

| Revicky et al. 2010 [32] | 32 | Para 0 | 3 h | 14 h | 40 | None |

| Beynon et al. 2011 [33] | 18 | Para 0 | 8 h postpartum | 4 h | 39 | Antibiotics and analgesics |

| Wozniak et al. 2011 [34] | 20 | Para 0 | 5 h postpartum | 9 h | 41 | Observation |

| Shrestha et al. 2011 [35] | 19 | Para 0 | N/A | N/A | 36 | None |

| Kuruba et al. 2011 [1] | 32 | Para 1 | 2nd stage | 1.5 h | 40 | None |

| McGregor et al. 2011 [36] | 27 | Para 0 | 2nd stage | 7.5 h | 40 | Oxygen and analgesics |

| Houari et al. 2012 [37] | 21 | Para 0 | Postpartum | N/A | 40 | Conservative management |

| Kandiah et al. 2013 [38] | 25 | Para 0 | 2nd day postpartum | 2nd stage 3 h, 16 min. Ending in a C-section | 40 | Observation |

| Kandiah et al. 2013 [38] | 30 | Para 0 | 2nd stage | 6 h | 38 | Observation |

| Kouki et al. 2013 [39] | 23 | Para 0 | 2nd stage | 9 h | 40 | Oxygen and analgesics and sedatives |

| Khoo et al. 2015 [40] | 33 | Para 0 | 2nd stage | 12 h | 40 | Analgesics and bed rest |

| Cho et al. 2015 [7] | 28 | Para 0 | 2nd stage | 5 h | 36 | Oxygen and analgesics |

| Wijesuriya et al. 2015 [41] | 24 | Para 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Khurram et al. 2015 [4] | 24 | Para 1 | 2 h postpartum | 2nd stage prolonged | 40 | None |

| Scala et al. 2016 [42] | 30 | N/A | 2nd stage | N/A | 40 | None |

| Elshirif et al. 2016 [43] | 27 | Para 0 | 4 h postpartum | 19 h 2nd stage 3 h | 41 | Analgesics, oxygen, and antibiotics |

| Berdai et al. 2017 [44] | 22 | Para 0 | 2nd stage | 2 h | 40 | Oxygen |

| Lou et al. 2017 [45] | 29 | Para 0 | 2nd stage | Prolonged | At term | Supportive |

| Sagar et al. 2018 [46] | 22 | Para 0 | 3 h postpartum | 4.5 h | 37 | None |

| Khan et al. 2018 [47] | 30 | Para 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Antibiotics, oxygen, and bronchodilators |

| Jakes et al. 2019 [48] | 23 | Para 0 | 40 min postpartum | 2nd stage 2 h | 38 | Oxygen |

| Madhok et al. 2019 [49] | 21 | Para 0 | 2 h postpartum | 3 h | 39 | None |

| Lee et al. 2019 [50] | 31 | Para 0 | 2nd stage | 8.4 h | 41 | IV antibiotics, hydrocortisone and Loratadine |

| Chavan et al. 2019 [51] | 33 | Para 0 | 10 h postpartum | 90 min 2nd stage | 38 | Oxygen and analgesics |

| Opstelten et al. 2019 [52] | 25 | Para 0 | 2nd stage | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Oshovskyy et al. 2020 [53] | 34 | Para 4 | 2nd stage | 4.5 h | 39 | Pigtail catheter |

| Badran et al. 2020 [54] | N/A | Para 0 | 4 h postpartum | N/A | Full term | Nil by mouth |

| Zethner-Møller et al. 2021 [55] | 35 | Para 1 | 2nd stage | N/A | 36 | Oxygen |

| Mullins et al. 2021 [56] | 17 | Para 0 | postpartum, prolonged second stage | N/A | 39 | Oxygen and opioids |

| La Verde et al. 2022 [18] | 23 | Para 0 | 2nd stage | 5 h | 41 | None |

| Gomes et al. 2022 [6] | 21 | Para 0 | 2nd stage | N/A | 40 | C-section and observation |

| Peña-Vega 2023 [57] | 18 | Para 0 | 30 h postpartum | 12 h | 39 | Oxygen |

| Chooi et al. 2023 [58] | 22 | Para 0 | 2nd stage | 3 h 2nd stage | 39 | None |

| Hülsemann et al. 2023 [59] | 21 | Para 0 | 2nd stage | Prolonged | N/A | N/A |

| Inesse et al. 2023 [60] | 29 | Para 0 | 1 h postpartum | 2nd stage lasted 2 h, 40 min active pushing | 40 | None |

| Chen et al. 2023 [61] | 20 | Para 0 | Immediately after delivery | Prolonged | 43 | Analgesics and antibiotics iv |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kuruba, N.; Hla, T.T. Postpartum spontaneous pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema: Hamman’s syndrome. Obstet. Med. 2011, 4, 127–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamman, L. Spontaneous mediastinal emphysema. Bull. Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1939, 64, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hamman, L. Mediastinal emphysema. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1945, 128, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurram, D.; Patel, B.; Farra, M.W. Hamman’s Syndrome: A Rare Cause of Chest Pain in a Postpartum Patient. Case Rep. Pulmonol. 2015, 2015, 201051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.G. Hamman’s Crunch: An historical note. Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 1971, 47, 1111–1112. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, S.; Mogne, T.; Carvalho, A.; Pereira, B.; Ramos, A. Post-partum Hamman’s Syndrome. Cureus 2022, 14, e33144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.; Parratt, J.R.; Smith, S.; Patel, R. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum (Hamman’s syndrome): A rare cause of postpartum chest pain. BMJ Case Rep. 2015, 2015, bcr1220103603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouritas, V.K.; Papagiannopoulos, K.; Lazaridis, G.; Baka, S.; Mpoukovinas, I.; Karavasilis, V.; Lampaki, S.; Kioumis, I.; Pitsiou, G.; Papaiwannou, A.; et al. Pneumomediastinum. J. Thorac. Dis. 2015, 7 (Suppl. S1), S44–S49. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, K.; Hongo, T.; Nojima, T.; Yumoto, T.; Nakao, A.; Naito, H. Hamman’s Syndrome Accompanied by Diabetic Ketoacidosis; a Case Report. Arch. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2022, 10, e68. [Google Scholar]

- Kamei, S.; Kaneto, H.; Tanabe, A.; Shigemoto, R.; Irie, S.; Hirata, Y.; Takai, M.; Kohara, K.; Shimoda, M.; Mune, T.; et al. Hamman’s syndrome triggered by the onset of type 1 diabetes mellitus accompanied by diabetic ketoacidosis. Acta Diabetol. 2016, 53, 1067–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kelly, S.; Hughes, S.; Nixon, S.; Paterson-Brown, S. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum (Hamman’s syndrome). Surgeon 2010, 8, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Früh, J.; Abbas, J.; Cheufou, D.; Baron, S.; Held, M. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum (Hamman’s syndrome) with pneumorrhachis as a rare cause of acute chest pain in a young patient with acute asthma exacerbation. Pneumologie 2023, 77, 430–434. [Google Scholar]

- Rosinhas, J.F.A.M.; Soares, S.M.C.B.; Pereira, A.B.M. Hamman’s syndrome. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2018, 44, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, G.M.; Franklin, V. Hamman and Boerhaave syndromes—Diagnostic dilemmas in a patient presenting with hyperemesis gravidarum: A case report. Scott. Med. J. 2014, 59, e12–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslaamizaad, Y.; Berrou, M.; Almalouf, P. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum (Hamman’s Syndrome): A Case Report. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 197, A6678. [Google Scholar]

- Jayran-Nejad, Y. Subcutaneous emphysema in labour. Anaesthesia 1993, 48, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, P.N.V.P.; Stefanini, F.S.; Bitencourt, A.G.V.; Gross, J.L.; Chojniak, R. Computed tomography-guided percutaneous drainage of tension pneumomediastinum. Radiol. Bras. 2022, 55, 62–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Verde, M.; Palmisano, A.; Iavarone, I.; Ronsini, C.; Labriola, D.; Cianci, S.; Schettino, F.; Reginelli, A.; Riemma, G.; De Franciscis, P. A Rare Complication during Vaginal Delivery, Hamman’s Syndrome: A Case Report and Systematic Review of Case Reports. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tixier, H.; Rattin, C.; Dunand, A.; Peaupardin, Y.; Douvier, S.; Sagot, P.; Mourtialon, P. Hamman’s syndrome associated with pharyngeal rupture occurring during childbirth. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2010, 89, 407–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneki, T.; Kubo, K.; Kawashima, A.; Koizumi, T.; Sekiguchi, M.; Sone, S. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in 33 patients: Yield of chest computed tomography for the diagnosis of the mild type. Respiration 2000, 67, 408–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jougon, J.B.; Ballester, M.; Delcambre, F.; Mac Bride, T.; Dromer, C.E.; Velly, J.F. Assessment of spontaneous pneumomediastinum: Experience with 12 patients. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2003, 75, 1711–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandfass, R.T.; Martinez, D.M. Mediastinal and subcutaneous emphysema in labor. South. Med. J. 1976, 69, 1554–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balkan, M.E.; Alver, G. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in 3rd trimester of pregnancy. Ann. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2006, 12, 362–364. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, F.W.; Ho, S.Y.; Campanella, C. Pneumomediastinum during spontaneous vaginal delivery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2002, 73, 314–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miguil, M.; Chekairi, A. Pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax associated with labour. Int. J. Obstet. Anesth. 2004, 13, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, B.L. Post partum pneumomediastinum. Anaesth. Intensive Care 2004, 32, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonin, M.M. Hamman’s syndrome (spontaneous pneumomediastinum) in a parturient: A case report. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2006, 28, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norzilawati, M.N.; Shuhaila, A.; Zainul Rashid, M.R. Postpartum pneumomediastinum. Singap. Med. J. 2007, 48, e174–e176. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, Y.; Ramesh, L.; Davies, J.A.; Nawaz, H.; Wheeler, R. Gross spontaneous pneumomediastinum (Hamman’s syndrome) in a labouring patient. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2008, 28, 651–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahboob, A.; Eckford, S.D. Hamman’s syndrome: An atypical cause of postpartum chest pain. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2008, 28, 652–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapardiel, I.; Delafuente-Valero, J.; Diaz-Miguel, V.; Godoy-Tundidor, V.; Bajo-Arenas, J.M. Pneumomediastinum during the fourth stage of labor. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2009, 67, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revicky, V.; Simpson, P.; Fraser, D. Postpartum pneumomediastinum: An uncommon cause for chest pain. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2010, 2010, 956142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beynon, F.; Mearns, S. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum following normal labour. BMJ Case Rep. 2011, 2011, bcr0720114556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wozniak, D.R.; Blackburn, A. Postpartum pneumomediastinum manifested by surgical emphysema. Should we always worry about underlying oesophageal rupture? BMJ Case Rep. 2011, 2011, bcr0420114137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, A.; Acharya, S. Subcutaneous emphysema in pregnancy. JNMA J. Nepal. Med. Assoc. 2011, 51, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGregor, A.; Ogwu, C.; Uppal, T.; Wong, M.G. Spontaneous subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum during second stage of labour. BMJ Case Rep. 2011, 2011, bcr0420114067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houari, N.; Labib, S.; Berdai, M.A.; Harandou, M. Postpartum pneumomediastinum associated with subcutaneous emphysema: A case report. Ann. Fr. Anesth. Reanim. 2012, 31, 728–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandiah, S.; Iswariah, H.; Elgey, S. Postpartum pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema: Two case reports. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 2013, 735154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouki, S.; Fares, A.A. Postpartum spontaneous pneumomediastinum ‘Hamman’s syndrome’. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, 2013, bcr2013010354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo, J.; Mahanta, V.R. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum with severe subcutaneous emphysema secondary to prolonged labor during normal vaginal delivery. Radiol. Case Rep. 2015, 7, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijesuriya, J.; Van Hoogstraten, R. Postpartum Hamman’s syndrome presenting with facial asymmetry. BMJ Case Rep. 2015, 2015, bcr2015213397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scala, R.; Madioni, C.; Manta, C.; Maggiorelli, C.; Maccari, U.; Ciarleglio, G. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in pregnancy: A case report. Rev. Port. Pneumol. 2016, 22, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshirif, A.; Tyagi-Bhatia, J. Postpartum pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema (Hamman’s syndrome). J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 36, 281–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berdai, M.A.; Benlamkadem, S.; Labib, S.; Harandou, M. Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum in Labor. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 2017, 6235076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, Y.Y. Hamman’s syndrome: Spontaneous pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema during second stage of labour. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 6, 2622–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sagar, D.; Rogers, T.K.; Adeni, A. Postpartum pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema. BMJ Case Rep. 2018, 2018, bcr2018224800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.I.; Shah, R.A.; Yasir, S.; Ahmed, M.S. Post partumpneumomediastinum (Hamman syndrome): A case report. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2018, 68, 1108–1109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jakes, A.D.; Kunde, K.; Banerjee, A. Case report: Postpartum pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema. Obstet. Med. 2019, 12, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhok, D.; Smith, V.; Gunderson, E. An Unexpected Case of Intrapartum Pneumomediastinum. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 2019, 4093768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.Y.; Young, A. Hamman syndrome: Spontaneous postpartum pneumomediastinum. Intern. Med. J. 2019, 49, 130–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavan, R. Hamman’s syndrome in a parturient: A case report. BJMP 2019, 12, a007. [Google Scholar]

- Opstelten, J.L.; Zwinkels, J.R.; van Velzen, E. Sudden dyspnoea and facial swelling during labour. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 2019, 163, D3044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oshovskyy, V.; Poliakova, Y. A rare case of spontaneous pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema in the II stage of labour. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2020, 70, 130–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badran, D.; Ismail, S.; Ashcroft, J. Pneumomediastinum following spontaneous vaginal delivery: Report of a rare phenomenon. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2020, 2020, rjaa076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zethner-Møller, R.; Wulff, C.B. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum during labour. Ugeskr. Laeger. 2021, 183, V05210403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mullins, K.V.J.; Mlawa, G. Postpartum chest pain and the Hamman syndrome. J. Clin. Images Med. Case Rep. 2021, 2, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Vega, C.J.; Buitrón-García, R.; Zavala-Barrios, B.; Aguirre-García, R. Postpartum Hamman (pneumomediastinal) syndrome. Synthesis of the literature and case report. Ginecol. Obstet. Mex. 2023, 91, 197–209. [Google Scholar]

- Chooi, K.Y.L. Hamman’s Syndrome: A Case of Pneumomediastinum, Pneumothorax and Extensive Subcutaneous Emphysema in the Second Stage of Labour. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Congress. Perth, 2021. Aiming Higher: More Than Healthcare. Poster No 80. Available online: https://ranzcogasm.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/80.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2019).

- Hülsemann, P.; Vollmann, D.; Kulenkampff, D. Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum-Hamman Syndrome. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2023, 120, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inesse, A.A.; Ilaria, R.; Camille, O. Protracted Labor Complicated by Pneumomediastinum and Subcutaneous Emphysema: A Rare Case Report and Management Considerations. Am. J. Case Rep. 2023, 24, e940989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Daly, T.K.; Nadaraja, R. Pneumomediastinum and Pericardium during Labour: A Report on a Rare Postpartum Phenomenon. Cureus 2023, 15, e50850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olafsen-Bårnes, K.; Kaland, M.M.; Kajo, K.; Rydsaa, L.J.; Visnovsky, J.; Zubor, P. Hamman’s Syndrome after Vaginal Delivery: A Case of Postpartum Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum with Subcutaneous Emphysema and Review of the Literature. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1332. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12131332

Olafsen-Bårnes K, Kaland MM, Kajo K, Rydsaa LJ, Visnovsky J, Zubor P. Hamman’s Syndrome after Vaginal Delivery: A Case of Postpartum Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum with Subcutaneous Emphysema and Review of the Literature. Healthcare. 2024; 12(13):1332. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12131332

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlafsen-Bårnes, Kristina, Marte Mari Kaland, Karol Kajo, Lars Jakob Rydsaa, Jozef Visnovsky, and Pavol Zubor. 2024. "Hamman’s Syndrome after Vaginal Delivery: A Case of Postpartum Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum with Subcutaneous Emphysema and Review of the Literature" Healthcare 12, no. 13: 1332. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12131332

APA StyleOlafsen-Bårnes, K., Kaland, M. M., Kajo, K., Rydsaa, L. J., Visnovsky, J., & Zubor, P. (2024). Hamman’s Syndrome after Vaginal Delivery: A Case of Postpartum Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum with Subcutaneous Emphysema and Review of the Literature. Healthcare, 12(13), 1332. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12131332