Effects of a Multicomponent Preventive Intervention in Women at Risk of Sarcopenia: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participant Eligibility

2.3. Multicomponent Intervention Approach

2.4. Outcome Measurements

Other Clinical Variables

2.5. Compliance

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Selection

3.2. Sample Size and Group Characteristics

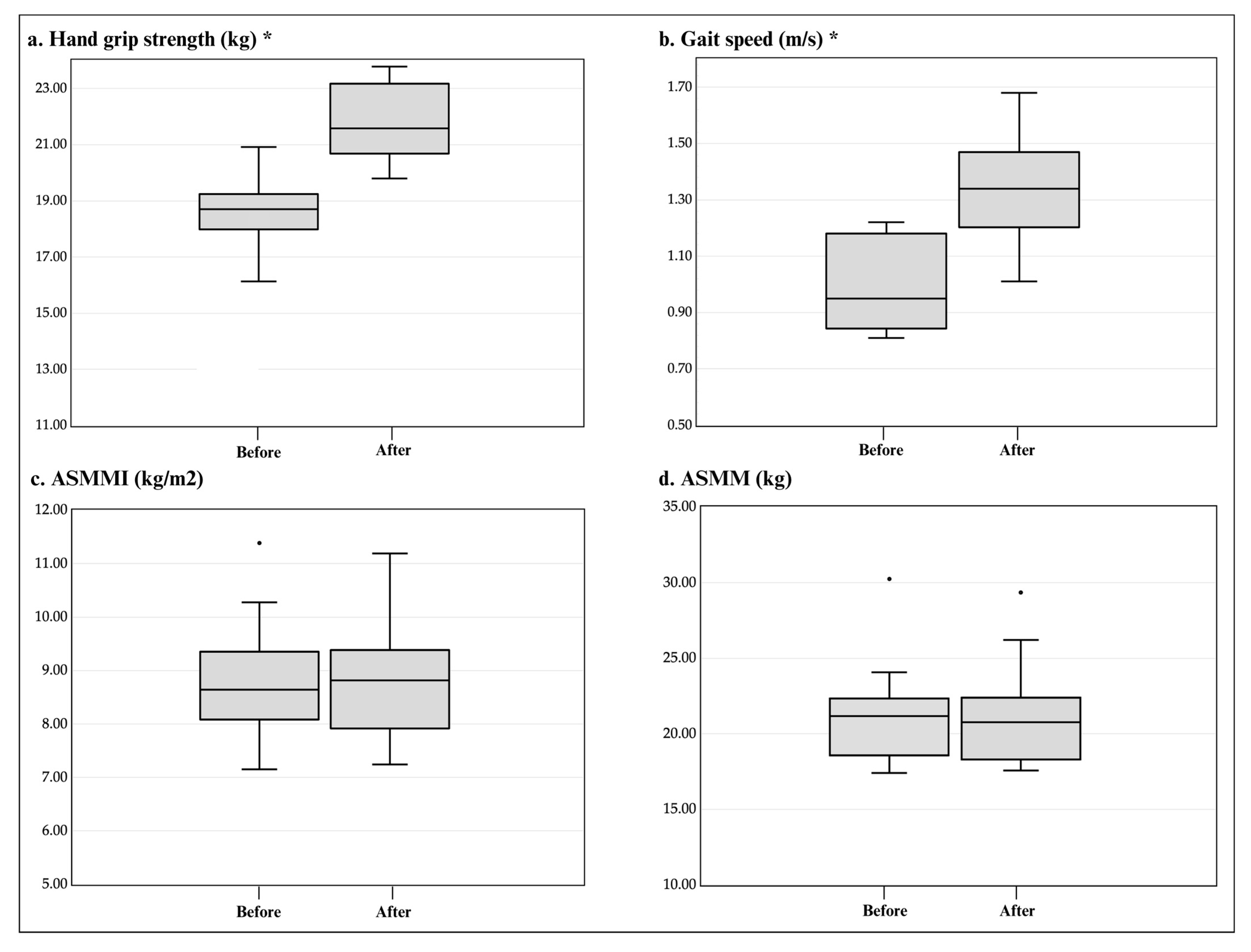

3.3. Effects of the Multicomponent Intervention

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, I.H. Sarcopenia: Origins and clinical relevance. J. Nutr. 1997, 127, 990S–991S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, I.H. Summary comments. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1989, 50, 1231–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, S.D.; Morley, J.E.; Von Haehling, S. Welcome to the ICD-10 code for sarcopenia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2016, 7, 512–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, A.I.; Priego, T.; López-Calderón, A. Hormones and Muscle Atrophy. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendón-Rodríguez, R.; Osuna-Padilla, I.A. El papel de la nutrición en la prevención y manejo de la sarcopenia en el adulto mayor. Nutr. Clínica Med. 2018, XII, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Ruiz, M.E.; Guarner-Lans, V.; Pérez-Torres, I.; Soto, M.E. Mechanisms Underlying Metabolic Syndrome-Related Sarcopenia and Possible Therapeutic Measures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petermann-Rocha, F.; Balntzi, V.; Gray, S.R.; Lara, J.; Ho, F.K.; Pell, J.P.; Celis-Morales, C. Global prevalence of sarcopenia and severe sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Baeyens, J.P.; Bauer, J.M.; Boirie, Y.; Cederholm, T.; Landi, F.; Martin, F.C.; Michel, J.-P.; Rolland, Y.; Schneider, S.M.; et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing 2010, 39, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, G.R.; Singh, H.; Carter, S.J.; Bryan, D.R.; Fisher, G.; Hunter, G.R.; Singh, H.; Carter, S.J.; Bryan, D.R.; Fisher, G. Sarcopenia and Its Implications for Metabolic Health. J. Obes. 2019, 2019, 8031705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L.V.; Paiva, A.E.G.; Silva, A.C.B.; de Castro, I.C.; Santiago, A.F.; de Oliveira, E.P.; Porto, L.C.J.; Fernandes, L.V.; Paiva, A.E.G.; Silva, A.C.B.; et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia according to EWGSOP1 and EWGSOP2 in older adults and their associations with unfavorable health outcomes: A systematic review. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 34, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinel-Bermúdez, M.C.; Sánchez-García, S.; García-Peña, C.; Trujillo, X.; Huerta-Viera, M.; Granados-García, V.; Hernández-González, S.; Arias-Merino, E.D. Associated factors with sarcopenia among Mexican elderly: 2012 National Health and Nutrition Survey. Rev. Med. Inst. Mex. Seguro Soc. 2018, 56, S46–S53. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Bachettini, N.P.; Bielemann, R.M.; Barbosa-Silva, T.G.; Menezes, A.M.B.; Tomasi, E.; Gonzalez, M.C. Sarcopenia as a mortality predictor in community-dwelling older adults: A comparison of the diagnostic criteria of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 74, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagarra-Romero, L.; Viñas-Barros, A. COVID-19: Short and Long-Term Effects of Hospitalization on Muscular Weakness in the Elderly. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musumeci, G. Sarcopenia and Exercise “The State of the Art”. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2017, 2, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadczak, A.D.; Makwana, N.; Luscombe-Marsh, N.; Visvanathan, R.; Schultz, T.J. Effectiveness of exercise interventions on physical function in community-dwelling frail older people: An umbrella review of systematic reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2018, 16, 752–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefflette, A.; Patel, N.; Caruso, J. Mitigating Sarcopenia with Diet and Exercise. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutz, N.E.P.; Bauer, J.M.; Barazzoni, R.; Biolo, G.; Boirie, Y.; Bosy-Westphal, A.; Cederholm, T.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.; Krznariç, Z.; Nair, K.S.; et al. Protein intake and exercise for optimal muscle function with aging: Recommendations from the ESPEN Expert Group. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.; Biolo, G.; Cederholm, T.; Cesari, M.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Morley, J.E.; Phillips, S.; Sieber, C.; Stehle, P.; Teta, D.; et al. Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: A position paper from the PROT-AGE Study Group. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 542–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J. The Effects of Protein and Supplements on Sarcopenia in Human Clinical Studies: How Older Adults Should Consume Protein and Supplements. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 33, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong Yan, A.; Nicholson, L.L.; Ward, R.E.; Hiller, C.E.; Dovey, K.; Parker, H.M.; Low, L.-F.; Moyle, G.; Chan, C. The Effectiveness of Dance Interventions on Psychological and Cognitive Health Outcomes Compared with Other Forms of Physical Activity: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2024, 54, 1179–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, L.H.; Rodrigues, E.V.; Filho, J.M.; da Silva, J.B.; Harris-Love, M.O.; Gomes, A.R.S. Effects of virtual dance exercise on skeletal muscle architecture and function of community dwelling older women. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2019, 19, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hwang, P.W.; Braun, K.L. The Effectiveness of Dance Interventions to Improve Older Adults’ Health: A Systematic Literature Review. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2015, 21, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Valdés-Badilla, P.; Guzmán-Muñoz, E.; Hernandez-Martinez, J.; Núñez-Espinosa, C.; Delgado-Floody, P.; Herrera-Valenzuela, T.; Branco, B.H.M.; Zapata-Bastias, J.; Nobari, H. Effectiveness of elastic band training and group-based dance on physical-functional performance in older women with sarcopenia: A pilot study. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinel-Bermúdez, M.C.; Ramírez-García, E.; García-Peña, C.; Salvà, A.; Ruiz-Arregui, L.; Cárdenas-Bahena, Á.; Sánchez-García, S. Prevalence of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older people of Mexico City using the EGWSOP (European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People) diagnostic criteria. JCSM Clin. Rep. 2017, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, B.E.; Haskell, W.L.; Herrmann, S.D.; Meckes, N.; Bassett, D.R., Jr.; Tudor-Locke, C.; Greer, J.L.; Vezina, J.; Whitt-Glover, M.C.; Leon, A.S. 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: A second update of codes and MET values. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1575–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM Information on… Protein Intake for Optimal Muscle Maintenance; American College of Sports Medicine: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schectman, O.; Sindhu, B. Grip. In Clinical Assessment Recommendations, 3rd ed.; MacDermid, J., Solomon, G., Valdes, K., Eds.; American Society of Hand Therapists: Mt. Laurel, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, Y.; Nishizawa, M.; Uchiyama, T.; Kasahara, Y.; Shindo, M.; Miyachi, M.; Tanaka, S. Developing and Validating an Age-Independent Equation Using Multi-Frequency Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis for Estimation of Appendicular Skeletal Muscle Mass and Establishing a Cutoff for Sarcopenia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esparza-Ros, F.; Vaquero-Cristóbal, R.; Marfell-Jones, M. ISAK Protocolo Internacional Para la Valoración Antropométrica. Perfil Restringido; ISAK: Murcia, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Generic care pathway. Person-centered assessment and pathways in primary care. In Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE): Guidance for Person-Centred Assessment and Pathways in Primary Care; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Shigematsu, R.; Chang, M.; Yabushita, N.; Sakai, T.; Nakagaichi, M.; Nho, H.; Tanaka, K. Dance-based aerobic exercise may improve indices of falling risk in older women. Age Ageing 2002, 31, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.Y.; Huang, K.S.; Chen, K.M.; Chou, C.P.; Tu, Y.K. Exercise, Nutrition, and Combined Exercise and Nutrition in Older Adults with Sarcopenia: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Maturitas 2021, 145, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Landi, F.; Schneider, S.M.; Zúñiga, C.; Arai, H.; Boirie, Y.; Chen, L.K.; Fielding, R.A.; Martin, F.C.; Michel, J.P.; et al. Prevalence of and interventions for sarcopenia in ageing adults: A systematic review. Report of the International Sarcopenia Initiative (EWGSOP and IWGS). Age Ageing 2014, 43, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Mao, L.; Feng, Y.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Liu, Y.; Chen, N. Effects of different exercise training modes on muscle strength and physical performance in older people with sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sink, K.M.; Espeland, M.A.; Castro, C.M.; Church, T.; Cohen, R.; Dodson, J.A.; Guralnik, J.; Hendrie, H.C.; Jennings, J.; Katula, J.; et al. Effect of a 24-Month Physical Activity Intervention vs Health Education on Cognitive Outcomes in Sedentary Older Adults: The LIFE Randomized Trial. JAMA 2015, 314, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.K.; Suzuki, T.; Saito, K.; Yoshida, H.; Kobayashi, H.; Kato, H.; Katayama, M. Effects of exercise and amino acid supplementation on body composition and physical function in community-dwelling elderly Japanese sarcopenic women: A randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, M.D.; Rhea, M.R.; Sen, A.; Gordon, P.M. Resistance exercise for muscular strength in older adults: A meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2010, 9, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Suzuki, T.; Saito, K.; Yoshida, H.; Kojima, N.; Kim, M.; Sudo, M.; Yamashiro, Y.; Tokimitsu, I. Effects of exercise and tea catechins on muscle mass, strength and walking ability in community-dwelling elderly Japanese sarcopenic women: A randomized controlled trial. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2013, 13, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, M.M.; Alonso, A.C.; Peterson, M.; Mochizuki, L.; Greve, J.M.; Garcez-Leme, L.E. Balance and Muscle Strength in Elderly Women Who Dance Samba. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keogh, J.W.; Kilding, A.; Pidgeon, P.; Ashley, L.; Gillis, D. Physical benefits of dancing for healthy older adults: A review. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2009, 17, 479–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong Yan, A.; Cobley, S.; Chan, C.; Pappas, E.; Nicholson, L.L.; Ward, R.E.; Murdoch, R.E.; Gu, Y.; Trevor, B.L.; Vassallo, A.J.; et al. The Effectiveness of Dance Interventions on Physical Health Outcomes Compared to Other Forms of Physical Activity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 933–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.K.; Leng, X.; Hsu, F.C.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Ding, J.; Earnest, C.P.; Ferrucci, L.; Goodpaster, B.H.; Guralnik, J.M.; Lenchik, L.; et al. The impact of sarcopenia on a physical activity intervention: The Lifestyle Interventions and Independence for Elders Pilot Study (LIFE-P). J. Nutr. Health Aging 2014, 18, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Han, J.; Gu, Q.; Cai, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, R.; Liu, X. Effect of Yijinjing combined with elastic band exercise on muscle mass and function in middle-aged and elderly patients with prediabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 990100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustosa, L.; Pereira, D.A.G. Impact of Aerobic Training Associated with Muscle Strengthening in Elderly Individuals at Risk of Sarcopenia: A Clinical Trial. J. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. 2014, 4, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Geografía y Estadística; Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública; Secretaría de Salud. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2018. Presentación de Resultados. 2018. Available online: https://ensanut.insp.mx/encuestas/ensanut2018/doctos/informes/ensanut_2018_presentacion_resultados.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Instituto de Geografía y Estadística. Módulo de Práctica Deportiva y Ejercicio Físico; CDMX, 2018; pp. 1–22. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/programas/mopradef/doc/resultados_mopradef_nov_2018.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Serrano-Guzmán, M.; Valenza-Peña, C.M.; Serrano-Guzmán, C.; Aguilar-Ferrándiz, E.; Olmedo-Alguacil, M.; Villaverde-Gutiérrez, C. Efectos de un programa de danzaterapia en la composición corporal y calidad de vida de mujeres mayores españolas con sobrepeso. Nutr. Hosp. 2016, 33, 1330–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemmler, W.; von Stengel, S.; Engelke, K.; Häberle, L.; Mayhew, J.L.; Kalender, W.A. Exercise, body composition, and functional ability: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 38, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, R.; Takeshima, T.; Kotani, K. Exercise Intervention for Anti-Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling Older People. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2016, 8, 848–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sociodemographic Characteristics (n = 12) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 55–65 | 10 (83.4) |

| 66–75 | 2 (16.6) |

| Education level | |

| Elementary | 4 (33.3) |

| High school | 8 (66.7) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 5 (41.7) |

| Single | 3 (25.0) |

| Divorced | 4 (33.3) |

| Occupation | |

| Housewife | 9 (75.0) |

| Employed | 3 (25.0) |

| Home | |

| Living alone | 7 (58.3) |

| Family living | 5 (41.7) |

| Health status characteristics (n = 12) | |

| Reported diseases | |

| Gastrointestinal | 9 (74.7) |

| Cardiometabolic | 8 (66.7) |

| Other | 4 (33.3) |

| Polypharmacy | |

| No | 9 (75.0) |

| Yes | 3 (25.0) |

| Comorbidity | |

| Absence of comorbidity | 10 (83.3) |

| Low comorbidity | 2 (16.7) |

| Functionality and Performance Markers, n = 12 | Basal Median (25th–75th) |

|---|---|

| Grip strength (kg) | 18.70 (17.98–19.23) |

| ASMMI (kg/m2) | 8.64 (8.08–9.35) |

| ASMM (kg) | 21.17 (18.58–22.33) |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 0.95 (0.81–1.18) |

| Variable, n = 12 | Pre-Test Median (25th–75th) | Post-Test Median (25th–75th) | p | ∆ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometric | Height (m) | 1.55 (1.53–1.56) | 1.55 (1.53–1.56) | 1.000 | 0.00 |

| Weight (kg) | 61.85 (54.47–75.85) | 60.65 (54.47–75.85) | 0.108 | −1.20 | |

| Circumference | Mean arm circumference (cm) | 30.70 (27.62–34.87) | 30.50 (27.27–33.95) | 0.444 | −0.20 |

| Waist (cm) | 89.10 (81.37–99.25) | 89.75 (78.75–97.12) | 0.328 | 0.65 | |

| Hip (cm) | 99.75 (94.75–110.37) | 97.65 (93.92–109.50) | 0.023 * | −2.10 | |

| Calf (cm) | 34.50 (31.87–37.15) | 33.65 (32.25–36.52) | 0.554 | −0.85 | |

| Body composition | Mass fat (%) | 36.55 (32.77–36.55) | 35.35 (32.52–37.70) | 0.308 | −1.20 |

| Mass fat (kg) | 22.60 (20.20–29.82) | 21.10 (17.70–21.10) | 0.182 | −1.50 | |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | 39.65 (35.62–45.50) | 40.15 (35.82–45.30) | 0.610 | 0.50 | |

| Visceral fat level (scores) | 9.00 (8.00–9.00) | 8.50 (7.00–8.50) | 0.157 | −0.50 | |

| Percentage of water (%) | 44.30 (43.52–46.27) | 45.60 (43.97–47.67) | 0.182 | 1.30 | |

| Intracellular water (L) | 14.90 (13.45–17) | 15.10 (13.37–16.85) | 0.326 | 0.20 | |

| Extracellular water (L) | 13.10 (11.90–15.17) | 13.15 (11.85–15.27) | 1.000 | 0.05 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.25 (23.36–25.25) | 24.84 (22.73–31.76) | 0.099 | −0.41 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rios-Escalante, V.; Perez-Barba, J.C.; Espinel-Bermudez, M.C.; Zavalza-Gomez, A.B.; Arias-Merino, E.D.; Zavala-Cerna, M.G.; Sanchez-Garcia, S.; Trujillo, X.; Nava-Zavala, A.H. Effects of a Multicomponent Preventive Intervention in Women at Risk of Sarcopenia: A Pilot Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1191. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121191

Rios-Escalante V, Perez-Barba JC, Espinel-Bermudez MC, Zavalza-Gomez AB, Arias-Merino ED, Zavala-Cerna MG, Sanchez-Garcia S, Trujillo X, Nava-Zavala AH. Effects of a Multicomponent Preventive Intervention in Women at Risk of Sarcopenia: A Pilot Study. Healthcare. 2024; 12(12):1191. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121191

Chicago/Turabian StyleRios-Escalante, Violeta, Juan Carlos Perez-Barba, Maria Claudia Espinel-Bermudez, Ana Bertha Zavalza-Gomez, Elva Dolores Arias-Merino, Maria G. Zavala-Cerna, Sergio Sanchez-Garcia, Xochitl Trujillo, and Arnulfo Hernan Nava-Zavala. 2024. "Effects of a Multicomponent Preventive Intervention in Women at Risk of Sarcopenia: A Pilot Study" Healthcare 12, no. 12: 1191. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121191

APA StyleRios-Escalante, V., Perez-Barba, J. C., Espinel-Bermudez, M. C., Zavalza-Gomez, A. B., Arias-Merino, E. D., Zavala-Cerna, M. G., Sanchez-Garcia, S., Trujillo, X., & Nava-Zavala, A. H. (2024). Effects of a Multicomponent Preventive Intervention in Women at Risk of Sarcopenia: A Pilot Study. Healthcare, 12(12), 1191. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121191